Style, statistics, and new models of authorship[1]<

Hugh Craig

University of Newcastle

Hugh.Craig@newcastle.edu.au

Hugh Craig. "Style, statistics, and new models of authorship". Early Modern Literary Studies 15.1 (2009-10). <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/15-1/craistyl.htm>.

I

- In this essay I

argue that humanities computing can change ideas about the role authors play

within texts and can offer a path to a new conception of authorship. My focus is on

computational stylistics in particular. The results of this practice tell us on

a statistical basis that texts reflect the styles of their authors to a

remarkable, perhaps unsuspected, extent. The results do not support the idea

that authors are insignificant as sources of meaning, but neither do they

license a return to an older idea of sovereign, hegemonic authors, as I hope to

show. The findings of computational stylistics can serve to test theories about

authorship and in turn to suggest modifications to those theories.

- The link between

theory and evidence has already been made by some commentators on authorship

influenced by postmodernism. They make a wager: they believe that a certain

theory about texts, which they hold to be valid, rules that attribution studies

cannot work. They predict that empirical methods for attribution will

necessarily be defeated by the variation within an authorial canon, and by

competing commonalities between texts. Computational stylistics, taking up this

challenge, can show that these predictions are false. This in turn suggests

that the theory on which the predictions were made is inadequate. A new theory

is needed which fits the new evidence.

- Putting it at its most

grandiose we can say that with computational stylistics we can for the first

time make a genuine connection between generalisation and detailed evidence

about style. In the case of authorship, statistical studies might have revealed

-- were free to reveal -- that authorship is insignificant in comparison to

other factors like genre or period. In that case the theory that authors are

only secondary to other forces in textual patterning would have been validated.

(For anyone brought up on the excitement of newly discovered cross-authorial

forces in texts -- like history, culture, and language itself -- that finding would

have been highly congenial.) As it happens, however, authorship emerges as a much

stronger force in the affinities between texts than genre or period (Craig, “Is

the author”). Unexpectedly, perhaps uncomfortably, it is a persistent, probably

mainly unconscious, factor. Writers, we might say, can’t help inscribing an

individual style in everything they produce. We need to take account of this in

a new theory of authorship.

II

- Computational

stylistics can be defined as the application of statistics to style. It was

established by John Burrows in the 1980s as a successor to stylometrics, which

was also a quantitative approach to texts, but more narrowly focused on making

yes-or-no determinations of authorship. Computational stylistics under Burrows took

advantage of the increasing amount of electronic text available and the

increasing processing power of the computer and aimed at a more holistic

treatment of style, going beyond the purely forensic.

- Computational

stylistics is a kind of inter-discipline, taking its methods from two powerful

and highly developed donor disciplines, statistics and linguistics, and

choosing its problems for analysis from a third, literary studies. It can also

make some significant returns to these disciplines. To statistics it can offer

a treasure trove of broad, deep and rich data, represented by what has been

called the “Very Large Textual Object” (Hope and Witmore). Even the modest

corpus I will discuss in this essay consists of several millions of instances

of tens of thousands of different vocabulary items, instances in series that

can be segmented in any number of naturally occurring ways, as speeches,

scenes, character parts, plays, genres, company repertories, and authorial

canons. This sort of test bed for statistical quantifiers and procedures is

hard to obtain elsewhere.

- Computational

stylistics has a small gift for linguistics as well: the revelation of the

depth and consistency of the styles of individual users and groups within

language, and the strength of stylistic difference within language generally, something

linguistics has rarely appreciated, intent as it is on language as such, or on

whole languages, whole historical periods, or on the language of very broad socio-linguistic

groups.

- Computational

stylistics’ dividend for literary studies, on the other hand, is, as I have

already hinted, the possibility of disciplined generalising. Literary scholars

have mostly preferred intensive analysis at the level of the image, the

passage, the character, or the individual work, and have then extrapolated from

that to broad programmatic pronouncements, which inevitably are far less

securely based than the intensive local analysis. With computational stylistics

we can, for the first time, test literary-theoretical paradigms against

empirical patterns in word-by-word linguistic performances. This work is just

beginning. At the moment it is often difficult to identify even where theory

and empirical studies could engage. Theories hardly ever make testable predictions

about texts, and tests are rarely well enough designed -- comprehensive enough,

or robust enough -- that the two sides agree on what has been found. Nevertheless

the nub of the present paper is the notion that in the case of authorship, a

challenge has been made and answered, and a result obtained: after two decades

or so of work, computational stylistics has established a strength and

consistency to the author effect in practice that overturns the consensus about

the invalidity of that effect in theory.

III

- In his influential

book on collaboration in Early Modern English drama, Textual Intercourse

(1997), Jeffrey Masten argues that shared authorship in these plays must be

revalued. He notes that in earlier work collaboration was often seen as a

scandal of sorts, a dilution and contamination of “pure” authorship (17, 19). Collaborative

works have often been treated as divided works whose parts are nevertheless the

products of individual authorship (16). He argues that collaboration should

instead be regarded as something like the norm, especially in the early modern

era, and especially in the drama, where the production that is the end point of

all labours must necessarily involve multiple agents (14, 20). This theory of

authorship as inevitably collaborative leads him to consider attempts to

separate the work of John Fletcher and Francis Beaumont in their joint plays as

misguided and doomed to disappointment. He adds other particular reasons to

expect efforts to attribute parts of plays to particular authors to end in

failure. Cyrus Hoy’s studies of Beaumont and Fletcher are a case in point. They

divide Beaumont and Fletcher plays between the two authors, on the basis of

“linguistic preferences” like ye for you and the contraction ’em

for them. Masten notes that Hoy omitted The Faithful Shepherdess

from his control set of Fletcher works because he saw it as different in style

from the others.

Whatever the other problems of method and evidence, this astonishing moment of deliberate omission seriously undermines Hoy’s project, and may alert us to the theoretical issues inherent in using “linguistic preferences” and “language practices” in the pursuit of essential and stable identities. These terms, indeed, may expose a problem now more fully legible through the lens of sexuality-theory: is Fletcher’s style chosen or innate? An act or an essence? Are his chosen practices preferred or performative? (17)

The implication here is that since style in writing, like gender, is a performance, not an essence, authors are free to vary it at choice and any stylistics that depends on the stability of authorial style is hopelessly compromised. Masten then lists other reasons to doubt that attribution in Early Modern drama based on stable linguistic habits could work. “[C]opyists, actors, [and] compositors” intervene between an author and the texts we have. Collaborators can be expected to influence each others’ styles. Playwrights deliberately write character parts in different styles, in this way “refract[ing] the supposed singularity of the individual in language” (17). What Masten calls “the presumed universality of individuated style” (17) depends in any case, he says, on “a historically inappropriate idea of the author” (18), based in its turn on notions like “intellectual property, copyright, [and] individuated handwriting” which developed after the period in which Beaumont and Fletcher were working (17).

- Masten’s views

about the impossibility of attribution derive from the postmodern

reconsideration of authorship, especially in essays by Roland Barthes, Michel

Foucault and Jacques Derrida. In this way Masten links quantitative attribution

study (and, indirectly, computational stylistics) with postmodern theory.

- Since Masten wrote

there has been some further contact between attributionists and postmodern

theorists, though more skirmishes en passant than as full engagements.

It is perhaps editors who have felt most strongly the friction between these

two forms of thinking. Editors who subscribe to postmodern theories tend to

find attributionists an irritant, since the latter raise problems which the

editors feel are inhibiting to their activity and less than fundamental to it.

On the other side attributionists have occasionally lamented the diminution of

interest in authors at the precise moment when new statistical means became

available to distinguish authorship (Merriam, Hoover). They have objected to

the so-called “death of the author” mostly in commonsensical terms. MacDonald P

Jackson reminds those who deny any importance to individual authorship in Early

Modern drama that someone did get paid even for the playbooks of the

Elizabethan theatre (80). Harold Love points out that it would make a great

difference to the scholarly community if a well-known essay by Foucault proved

to be in fact the work of a minor disciple: it might “put into question our

whole understanding of Foucault and his ideas” (96-7). Brian Vickers,

challenging the notion that individual authorship and all that goes with it is

purely a modern phenomenon, quotes the emphatic declarations of personal

authorship within Virgil’s Eclogues and Horace’s Odes (Vickers, Shakespeare

512).

- My sense is that

the debate has reached a stalemate. My purpose here is to try to advance the

discussion by seeking a ground on which theory and practice in authorship could

meet. The approach that comes closest to my own here is that of Burrows, who

has already tackled this question, in a 1994 lecture, published in 1995. There

he demonstrated a deep authorial difference in the language of two Restoration

poets, a persistent and marked contrast in the way the two writers use a common

language on shared topics. He concluded that the onus was now on the followers

of Foucault, who declare authorship to be something constructed entirely after

the fact, to respond to the powerful computational evidence of an authorial

effect within texts.

- Nevertheless, the

evidence Burrows offered in his piece, and the similar evidence which he has

published before and since,[2]

and that others have published, following his lead,[3] has not in fact

resolved the question, any more than the robust Johnsonian reminders of evident

truths already mentioned. Scholars (some of whom are quoted below) continue to

declare that the older authorship model, the one which made authorship the

chief guarantor and constituting power of meaning in texts, has been broken,

and move on to argue that authorship is severely compromised as a key to

understanding textuality and as a basis for interpretation and editing, and

that attribution work is doomed to failure and redundancy. Meanwhile

attributionists continue to claim that their methods work and reveal

significant aspects of texts.

IV

- In principle, the

dethroning and guillotining of the sovereign author, performed with gusto in

Roland Barthes’ “La Mort de l’Auteur” (first published, in English translation

as it happens, in 1967) and in Michel Foucault’s “Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur”

(1969), do not invalidate attribution. The author might be reduced to an

insignificant “figurine” at the far end of the literary stage (Barthes, “Death”

145), it might be the language that speaks in a text, not the author (Mallarmé,

qtd. in Barthes, “Death” 143), all this might be true and characteristics of

individual authors inscribed in texts could still serve to identify the

historical individual who made the original marks on the page, the entity

Barthes calls the “scriptor” (“Death” 145). Indeed, Barthes himself is

supremely attuned to an effect of contact with an individual (apparently)

originating voice, both in the literal sense of a physically embodied sound

(“the grain of the voice” (Barthes, “Grain”)) and in the virtual sense as the

voice speaking a text. “[I]n the text,” he says in his 1993 book The

Pleasure of the Text, “in a way I desire the author: I need his

figure (which is neither his representation nor his projection) as he needs

mine . . .” (27)

- In an earlier work he has some eloquent remarks on authorial style

and its origins in “the depths of the author’s personal and secret mythology,

that subnature of expression where the first cognition of words and things

takes place, where once and for all the great verbal themes of his existence

come to be installed” (Writing 10). He says the secret of style is

“recollection locked in the body of the writer” (Writing 12). Indeed,

Barthes’ thinking on authorial style would make a very worthwhile study in

itself, building on the analysis in Seàn Burke’s book on The Death and Return of the Author (33-41,

58-61).

- It is consistent to accept that some traces of the scriptor’s

individuality are inscribed in texts, but to relegate that scriptor to a minor

role in the creation of meaning, and thus to regard attribution studies as

feasible but largely irrelevant. However, a number of scholars, like Masten,

who subscribe to a postmodern theory of authorship, and who turn their

attention to attribution studies, do not rest with downplaying the importance

of these studies; they also commonly make observations about the techniques of

attribution, declaring that attribution is impracticable as well as redundant.

They make the assumption that authorship theory has consequences for the

details of attribution practice. In turn the perceived failure of attribution

techniques are seen as confirmation of the theory.

- Here a distinction

made by Burke towards the end of his book is useful. The postmodernists’ “death

of the author” was a bold challenge to theories of interpretation. It was, we

might say, a very productive hypothesis. After all, as

Andrew Bennett points out, in a sense authors are necessarily dead. Writing

exists to preserve language in the absence of the author, and leaves the author

behind (10-11). From another point of view, it would be naïve to think that

authors are wholly and exclusively responsible for bringing a piece of writing

into being. The language writes as well (as Mallarmé said). The Foucauldian episteme,

the whole system of knowledge at any particular historical juncture, is

writing. Authors settling down to write are constrained by the genre in which

they choose to write, or are required to write, and more generally by an

audience’s expectation.

- The author is also

something that postdates composition, a construction required to make writing

function in ways that suit particular societies and institutions. This kind of

author is only indirectly and obliquely related to the flesh and blood

individual who holds the pen or strikes the keys. The “death of the author”

(or, to move from Barthes to Foucault, the replacement of the author with the

“author-function”) brought this truth to the fore and opened the way to the

history of the book as we now know it and to so much else.

- This version of

the “death of the author,” which Burke calls “a speculative experimental

approach to discourse” (173), has been spectacularly fruitful for the

humanities. By contrast “the death of the author” has also been understood by

some as “the truth of writing itself”, “a matter of cognitive certitude” (Burke

173). Here the implications have (arguably) been less helpful. In their

eagerness to attack one particular notion of the author -- the transcendental

subject -- Barthes, Foucault and Derrida sometimes, and their followers often,

write of the death of the author as itself an article of faith, a dogma that

would open the way to an ecstatic liberation in literary interpretation and

beyond. Confusingly, this death of the author was something that had already

happened and must continually be re-enacted. The author was both a

trans-historical delusion and an ideology born around 1800. In the wake of this

powerful call to arms, a whole generation of critics dedicated themselves to

eradicating the author-principle whenever possible, tackling it both as a

powerful enemy of truth and free interpretation and as a mere phantasm whose

power had been continually overestimated.

- This kind of

“death of the author” is more an article of faith than a heuristic device. It

derives from an element of conscious paradox and calculated excess in the

postmodernists of the sixties. It has certainly been challenged in recent years,

for example in feminist studies, where the originating author is necessarily

important, at least to the extent of her or his gender, and elsewhere in more

general terms (Burke; Grosz 9-24; Knapp; Vickers, Appropriating 101-15).

Nevertheless the dogmatic version has a continuing strong presence in Early

Modern studies. Examples of this can be found in Masten’s book Textual

Intercourse, already quoted, and in an influential article on “The

Materiality of the Shakespearean Text” by Margreta de Grazia and Peter

Stallybrass (273-9). The textual theory of Graham Holderness and Bryan Loughrey

is also uncompromising in its adherence to postmodern ideas about the author.

They prefer to put Shakespeare in inverted commas, as “the shorthand title

designating a particular collaborative mechanism of cultural production.” They

“deny the possibility of any claim that ‘Shakespeare wrote’ the texts of the

Shakespeare canon, if by that assertion is intended a clear, unmediated and

controlling relationship between author and text” (17). Given this remoteness

of texts from authors, empirical work on attribution must necessarily be weak.

Holderness says “there is really very little evidence to support the many

‘disputed authorship’ theories” (34). Similarly, John D. Cox and Eric Rasmussen

say that “recent developments suggest that the question of authorship [of plays

like 3 Henry VI] has not been resolved because it is unresolvable.” One

of these developments is Barthes’ “challenge to the idea of authorship itself”

(47-8). Gordon McMullan has pursued the connections between postmodern theory

and attribution with especial thoroughness. His work is particularly relevant

here because he makes some very specific challenges to the practice of

assigning plays or parts of plays to particular authors on the basis of

empirical measures of style. In addition, there has already been a debate

between McMullan and Vickers over authorship, which has crystallised many of

the issues (Vickers, “Review,” Shakespeare 397-402, “Incomplete” 348;

McMullan, Shakespeare 234-43).

V

- The problem arises

for McMullan because of the collaborative authorship of Henry VIII,

which he has edited for the third Arden Shakespeare series. McMullan accepts

that Shakespeare worked with Fletcher on the play, but he believes that it is

not profitable to divide the play between them, or to analyse parts of the play

on the basis of separate authorship. His reasoning in support of this position

is familiar from Masten’s work: he declares that authors are not important as

sources of meaning in writing, following Foucault, and, secondly, more

pragmatically, that attribution methods do not work.

- McMullan puts his

views in a 1996 article in the journal Textus (on collaboration and its

implications for editing), in his Henry VIII introduction of 2000, and

in his 2007 Cambridge book on the late style of Shakespeare and others. An

extended critique like this is (oddly enough) a boon for those who practise

authorial attribution, certainly far more useful than the more usual approach

of passing over the disagreements in silence. McMullan’s second set of

arguments, about attribution, moves off the high ground of pure theory and into

territory where computational stylistics might hope to engage. McMullan, as I have

mentioned, offers a series of challenges to attribution. Each of them, I think,

computational stylistics can meet. My hope is that one can then move from this

level back to the more theoretical one.

- McMullan’s list of

reasons why attribution studies cannot work overlaps with Masten’s (indeed he

cites Masten at many points) but is worth rehearsing because it takes us to our

specific example. He argues that attributionists have not taken account of the

fact that authors write differently in different genres (Henry VIII 193n

and 196), and at different stages of their careers (Henry VIII 195).

Dramatists, in particular, deliberately set out to differentiate styles within

a play, in creating contrasting idiolects for their various characters, and

this must undermine attribution on the basis of a consistent authorial style

(“Our Whole Life” 449; Henry VIII 195). McMullan follows Masten’s book

in emphasising that drama is in its nature collaborative, dispersing authorial

agency among actors, stage crew, even theatre companies (Shakespeare

238-42). From a historical point of view, in any case, individual authorship is

an anachronism in Early Modern texts (“Our Whole Life” 444). Then the whole

notion of identifying sources for texts “compromises the notions of authority

fundamental to attributive study” (Henry VIII 174). Moreover, when

writers collaborate, their styles are likely to converge, thus rendering it

impossible to tell them apart on the basis of their practice as solo authors

(“Our Whole Life” 452).[4]

McMullan notes that attributionists have observed changes in the way a

character talks in a collaborative work, as one writer takes over from another,

but he points out that these are not necessarily authorship effects. He says the

change may well relate to the character, not to the writer. Even if we agree

that Queen Katherine in Henry VIII does change at a particular juncture

in the play which is also (very likely) a join between two authors’ parts, we

cannot discount the fact that the change may arise from something intrinsic to

the character, rather than from alternating authorship -- a change in her

circumstances, for example, or a change in her political strategy (Shakespeare

237).

VI

- According to

McMullan, then, there are abundant good reasons to distrust any project to

divide a play like Henry VIII between its collaborators. I will present

a computational-stylistics study of the play which I think meets each of his

challenges to attribution.[5]

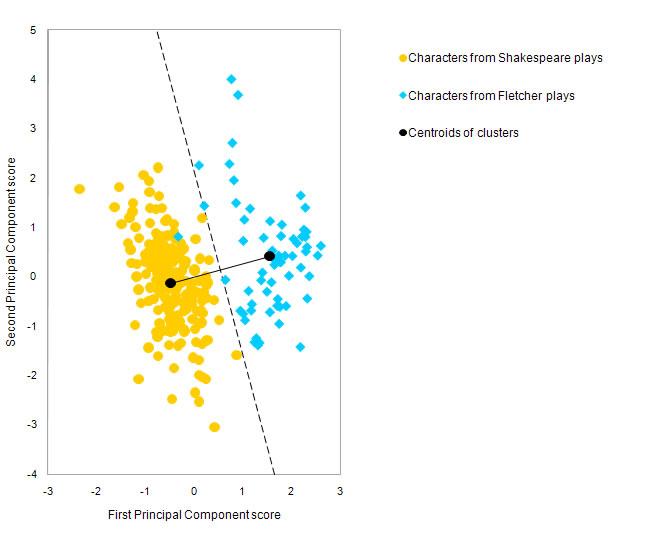

Figure 1 shows a mapping of Shakespeare and Fletcher characters using the combined frequencies of forty words.

Figure 1

- Shakespeare

characters are the yellow discs and Fletcher characters the blue diamond

shapes. The Shakespeare set comprises all the characters speaking more than a

thousand words in the twenty-seven plays which can be regarded as a core

Shakespeare canon[6]

(199 characters in all). The Fletcher set comprises sixty-two characters, all

those with a thousand or more words in the seven Fletcher plays which were chosen

to be prepared in machine-readable form for the analysis. Unlike the

Shakespeare set, this is only a sample of what is available by way of

sole-author well-attributed Fletcher plays (there are fifteen of these in all,

if you exclude those thought to be revised by others (McMullan, Unease

267-9)). However, the seven plays in the set do include representatives of all

the genres Fletcher wrote in over the course of his career (tragedy, comedy,

tragicomedy and pastoral), and include the six sole-author Fletcher plays

written in Shakespeare’s lifetime.

- In the texts two

hundred function words (words with a grammatical function rather than a lexical

one, like and and you) were standardised so that where

appropriate “Ile” counts as an instance of I and one of will (verb),

“that’s” as an instance of that (demonstrative) and one of is,

and so on. From these two hundred words those which Shakespeare and Fletcher

habitually use at markedly and consistently different rates were selected.[7] The frequencies of these

forty ‘marker’ words have been combined in two different ways to make two

indexes, the X and Y axes of the graphs. These are indexes in the sense of the

Dow Jones Index -- a summary score for a series of variables, weighted to give

some a greater impact on the result than others. A mathematical procedure

called Principal Component Analysis has created the two indexes. The First

Principal Component (the X axis) is the most important latent factor in the

various correlations between the word-variables in the character-texts and the

Second Principal Component is the second most important latent factor.

- The methods for

calculating these factors are well established and do not need to detain us

here.[8] All we need to remark

is that each character in the set is given two scores, one for the first

principal component, and one for the second principal component. Each score

derives from the character’s count on the forty words -- how many instances of the,

of my, of would, etc -- with the counts weighted in one way for

the first principal component and another way for the second principal

component. What we are looking at in the graph is a form of “data reduction”, a

distillation of all the patterns of fluctuation in the various counts. We start

with forty dimensions, one for each of the word-variables, and PCA allows us to

project these forty dimensions onto two, and it is this projection that appears

in the graph.

- A number of the

speculative challenges to quantitative attribution which McMullan throws out

are answered here. Authors may write character parts that are different in

style from each other, and authors may vary in the way they write according to

genre and period, but these variations remain within bounds, and hardly ever

compromise an overall separation between authors. We can make this a little

more specific by dividing the graph formally into “Shakespeare” and “Fletcher”

areas.

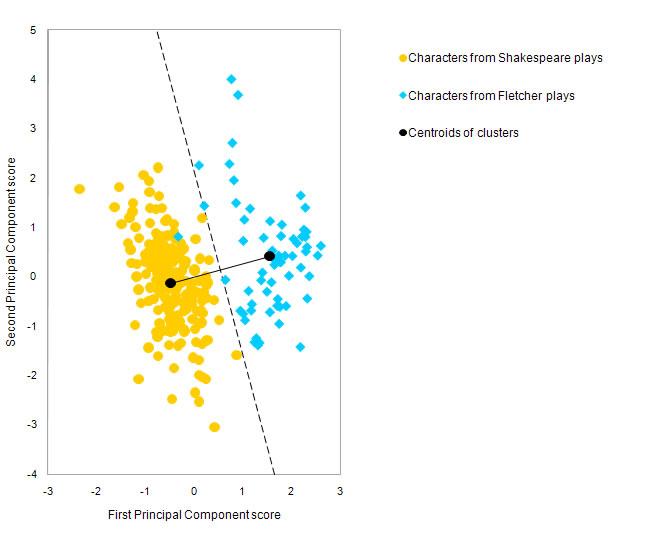

Figure 2

- The black dots are

the central points, or “centroids,” as they are called, for each cluster. The

coordinates for these points are the average values on each axis for each

cluster. A solid line joins the two centroids. A second, dashed line, which

passes through the mid-point between the two centroids at right angles to the

original line, can serve as a rough-and-ready way to divide the graph. All 199

Shakespeare characters are to the Shakespeare side of the line. Of the

sixty-two Fletcher characters, just one appears on the Shakespeare side. This

is the Sullen Shepherd from the pastoral The Faithful Shepherdess. As

already noted, this play was excluded from Hoy’s Fletcher control group because

it was so atypical in style. The graph shows that in our analysis one character

from the play does evidently vary so much from Fletcher’s usual style of

dialogue that he looks on this analysis like a Shakespeare character, but he is

an exception. The eight other characters from The Faithful Shepherdess

we included are correctly placed with the other Fletcher characters.[9] The three Fletcher

characters closest to the borderline in Figure 2 are, from the top, Rowland

from The Woman’s Prize, Fletcher’s sequel to The Taming of the Shrew,

the Satyr from The Faithful Shepherdess, and Jaques, another character

from The Woman’s Prize.

- Using nothing more

than the counts for some very common words, then, one can establish a set of

indicators which places Hamlet with Polonius, Hal with Falstaff, Viola with

Olivia, and all of them away from Fletcher characters like Amoret, Bonduca,

Putskie, Valentinian and so on. There is the occasional overlap of the two

groups, but the overwhelming majority of Shakespeare and Fletcher characters

fall neatly into one or other authorial cluster.

- The characters in

Figure 1 all come from plays which scholars agree are the unaided work of one

or other playwright. What happens with a collaborative play like Henry VIII?

Figure 3 shows the same analysis as Figures 1 and 2, based on the same

variables treated the same way, but this time including six new entries, two

each for the King, the Queen, and Cardinal Wolsey, the three characters from

the play which have both 1000 words or more written by Shakespeare and 1000 or

more written by Fletcher. To establish the two author-based parts of the three

characters I have relied on the division of the play proposed by James Spedding

in 1850, supported by many studies since, and summarised and further tested by

Vickers in his book Shakespeare, Co-Author (Oxford, 2003).

Figure 3

- Despite the

“accommodation effect” McMullan predicts (“Our Whole Life” 452), in which

collaborative authors, like speakers in a conversation, would tend to converge

in style, the character-parts Shakespeare and Fletcher wrote for Henry VIII

remain distinct. The parts of Queen Katherine’s dialogue written by Shakespeare

are marked by a red disk, and the parts of her dialogue written by Fletcher are

marked by a red diamond. Thus she speaks like other Shakespeare characters when

her part is written by Shakespeare, and like other Fletcher characters when it

is written by Fletcher. The same is true for King Henry (a black disc and a

black diamond) and Cardinal Wolsey (a grey disc and a grey diamond). These new

entries have played no part in the selection of the words to use as variables,

so they are treated as truly anonymous. The two writers, one would think, have

every interest in writing like each other, so as to produce seamless drama, and

yet their character parts diverge and follow their separate patterns of

function word use.

VII

- As we have seen,

some exponents of postmodern authorship theory claim that the nature of

authorship as specified by the theory will necessarily result in failures in

attribution experiments. In the case of claims like this made about Shakespeare

and Fletcher and Henry VIII, they were shown to fail. On that showing,

authorship does not operate the way these theorists predicted.

- Of course it will

take more than one set of graphs to change the minds of those who believe that

in Early Modern drama, and in writing in general, countervailing forces in

textual production reduce the role of authorship to something vanishingly

small. It will take a series of such demonstrations, for one thing. Then it

will take something more -- a theory to go with them. There is a story, no

doubt apocryphal, about a long tussle in the European Union over a British

proposal. Finally the French representative said, “I can see that it will work

in practice, but will it work in theory?” We need to show that computational

stylistics works in theory as well as in practice.

- One crucial step

towards this theory was taken when Burrows showed that authorial individuality

is present not only in usage of the commonest words, like the ones used in the

graphs for this paper, but also in usage of the fairly common and even the rare

words as well. His “postulate” to go along with the presentation of his results

is that “Evidence of authorship pervades whatever anyone writes. Provided

appropriate procedures are employed in the analysis of an appropriate set of

texts, it can almost always be elicited” (Burrows, “All the way” 28).[10]

- So how to explain

this powerful and pervasive force? One way is via cognitive science, which

tells us that language production is largely unconscious (Lancashire 173,

177-80). This is less true for writing, where one can pause and revise; but for

fluency in writing as well as in speech, language comes from a part of the

brain occluded from consciousness. This would help explain the limits to

variation in a writer’s style. Writers are “blind to the process that gives rise

to the utterances they make” (Lancashire 177). It follows that important

aspects of style may indeed be governed by operations over which the writer for

the most part has no conscious control. These aspects can then serve as

reliable indicators of authorship. This goes for the long-term memory, where we

store experiences, as well: retrieval happens instinctively and by association

rather than any formal structure. According to Ian Lancashire

[t]he organisation of memories . . . reflects the person’s own past experience and thought rather than a shared resource of cultural knowledge. While people may remember the same things, they seldom store them in similar associational matrices. The associational matrix seems to me to require that a person’s speech or writing will exhibit a unique idiolect. (178)

Authors have often reported that literary creation is an unconscious process, as in the classical doctrine of inspiration. In the early nineteenth century William Blake said he wrote Milton “from immediate Dictation . . . without Premeditation & even against my Will” (qtd. in Bennett 61). Cognitive science has rediscovered this idea.

- The relatively new

practice of cognitive stylistics also offers pathways to a theory that would

underpin the findings of computational stylistics, since it aims “to locate in

texts signs of their origins in a materially embodied mind/brain” as well as trace

the effects of cultural forces (Crane 4). The intimate connections between the

physical self of the individual and patterns in language have been further

demonstrated by studies of the changes in writing brought about by brain

pathologies like dementia (Garrard; Hirst and Lancashire). In Crane’s words,

“Within Shakespeare’s brain culture and biology meet to form him as a subject

and to produce his texts” (15) and a new authorship theory must take

account of this fact.

- Another part of

this new theory is more properly literary: in striving to communicate to the

unseen and unknown audience, one important enabling device is a personal style,

creating a connection through the illusion of the presence of a recognisable

individual. Here Barthes’ discussion of the functioning of a perceived

authorial style in the reader is important.

- As well as a

theory of style, and a theory of authorship that connects with style, we need

to explain what sort of links there can be between computation and style. One

aspect of this is a connection between some essential properties of language

and the subtle numerical cumulations and contrasts for which statistics is

designed. Writers and readers possess language in common. For communication to

work, both sides must share a vocabulary and a set of grammatical rules. This

might seem to limit creativity, but in fact a more or less unlimited set of utterances

can be created by varying selections from the common set, varying the ordering

of common vocabulary items, through repetition and through suppression. Steven

Pinker calls this aspect of language an “infinite use of finite media.”

Language works in a “combinatorial” way relying on “discrete” and repeatable

elements (84-5). Statistical procedures like PCA are well adapted to summarise

and differentiate profiles like these. Far from crushing nuances and

relationships as literary scholars might fear, these mathematical tools can

refract and focus patterns in a corpus and make them explicit and available for

analysis. Computational stylistics is not a crude, tone-deaf approximation to

the literary but a method in harmony with the fundamental principles of

language.

- A new authorship

theory based on the evidence from computational stylistics will restore some

importance to the individual author but it will not be a return to the older

dispensation, to what McMullan calls “post-Romantic” (Shakespeare 228,

254) or “subjectivist” (Shakespeare 233, 235, 255) ideas of authorship.

It is probably true to say, as McMullan does, that “critical developments since

the late 1960s have enabled a certain liberation . . . from the romantic

philosophy that underlies the critical insistence upon solitary inspiration” (Henry

VIII 6) -- or at least that we can return to the idea of inspiration by a

different route.

- Computational

stylistics in some ways is more in step with postmodernist thinking than with

the older ideas about entirely self-sufficient authors. For one thing,

statistics depend on comparison and are always relative. A number is only big

or small in relation to other numbers. Calculation can only define style

relationally -- it highlights features characterising author X’s language use

as against author Y’s, or against that of twenty-five other authors -- and

never absolutely. Computational stylistics cannot pretend to reveal any

essences, only a highly pragmatic differentiation of one thing from another. Bring

in a third entity and things change appreciably. For another, the idea of

unconscious language production complicates intentionality. Writing is

individuated by the originating mind, but that mind is distinct from the

self-aware subject. The latter’s sovereignty over writing is shared rather than

absolute.

- Individuality in authorship re-emerges through computational stylistics in a new form: not a mysterious, ultimately theological interiority but a pressure to create a distinctive identity in language, part cultural and part biological. The competing forces that disperse authorial agency, the ones we have heard so much about in recent decades (and nowhere more than in discussions of early modern English drama), are there, of course, but so is an opposite force, the drive to create despite everything an individual distinctive style. Georges Braque offers an apposite formulation: “One’s style -- it is in a way one’s inability to do otherwise” (Liberman 145). Computational stylistics cannot provide all the necessary elements of a new model of authorship, but it can endorse the dethroning of the older hegemonic author-subject and at the same time challenge the newer absolutism of those who deny authorial style ex cathedra any role in the functioning of the text. With the unlikely help of the graphs and tables of computational stylistics we may glimpse the beginnings of a new “evidence-based” model of the relationship between writer and writing, a model which will accommodate the persistent but varying strength of individuated authorship in texts, and record the outcomes of the ceaseless textual negotiations between that force and its competitors like collaboration, genre, discourse and period.

[1] This paper was given as a keynote address at the 2008 Resourceful Reading conference at the University of Sydney. I am grateful to the organisers, Katherine Bode and Robert Dixon, for inviting me to the conference. I am also grateful to the University of Newcastle (NSW) Writing Cultures Research Group, and to Rosalind Smith, for very helpful comments on the paper in its earlier forms.

[2] E.g. Burrows. “’I lisp’d’”, “Computers.”

[3] E.g. Craig, “Is the Author” and Forsyth, Holmes and Tse.

[4] E. H. C. Oliphant and E. K. Chambers both thought Fletcher had modified his style in his part of Henry VIII (Vickers 347). There are no signs of this “accommodation” in the function-word data I have analysed, as discussed below. In other studies, not reported here, I did find some convergence between Fletcher and Shakespeare in lexical word patterns in the play.

[5] It is worth mentioning that McMullan’s critique is not directed to computational stylistics as such, but rather at the wider movement of scholars using all kinds of quantitative measures in attribution. He notes in the 2000 Henry VIII introduction that computational methods are not yet widely accepted (“because of incompatible fields of understanding both about the nature of statistical study and about the significance of ‘literary’ concepts such as genre”) and anticipates better results once more extensive electronic corpora of the plays are available (193n).

[6] These are the twenty-eight plays listed as fitting “a minimal definition of the Shakespeare canon, excluding all works of doubtful or collaborative status” in a table in the Oxford Shakespeare Textual Companion (Wells, Taylor, Jowett and Montgomery 81 and Table 2). From this group I have excluded Measure for Measure, which is now generally regarded as a collaboration with Middleton (Jowett 681-2).

[7] The words are

are again all as being can dare did do doth each ever hath hence in (preposition) itself only may might more must my now of quite rather still that (conjunction) the there these those to (preposition) too very which (relative) who (relative) with ye yetFor each of these word-variables the probability that the Shakespeare and Fletcher character parts belonged to the same parent population was less than 0.0005, according to the t test. Function words are the best understood variables in computational stylistics, having been used regularly for authorship attribution since Frederick Mosteller and David L.Wallace’s work on the Federalist papers in the 1960s.

[8] For a full presentation, see Chatfield and Collins (on the method) and Burrows and Craig (on applications to stylistics). Calculations were performed with SPSS 16.0, analysing the correlation matrix and using an unrotated factor solution.

[9] McMullan follows Masten in noting that both Hoy, and Jonathan Hope in his Shakespeare-Fletcher study, omit The Faithful Shepherdess from their Fletcher control sets because this play is so unlike the rest of the Fletcher canon in style. McMullan regards this as more evidence that attribution studies are inevitably compromised by the variation within authorial canons (Politics 451).

[10] He adds: “It is inherent, however, not merely in statistical principle but in human behaviour at large, that such evidence cannot be absolute. The consistencies we observe are trends, not universals” (28-9).

Works Cited

- Barthes, Roland. "The Death of the Author." Image-Music-Text. Trans. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill, 1977. 142-8. Trans. of "La Mort De L'auteur." Manteia 5 (1968), n.p.

- Barthes, Roland. “The Grain of the Voice.” Image -- Music -- Text. Trans. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 179-89. Trans. of “Le grain de la voix.” Musique en Jeu 9 (1972): 57-63.

- Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text. Trans. Richard Howard. London: Cape, 1976. Trans. of Le Plaisir du Texte. Paris: Le Seuil,1973.

- Barthes, Roland. Writing Degree Zero. Trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith. New York: Hill and Wang, 1968. Trans. of Le Degré Zero de l’Ecriture. Paris: Le Seuil,1953.

- Bennett, Andrew. The Author. New Critical Idiom. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Burke, Seàn. The Death and Return of the Author: Criticism and Subjectivity in Barthes, Foucault and Derrida. Second edition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998.

- Burrows, J F. "'I Lisp'd in Numbers': Fielding, Richardson and the Appraisal of Statistical Evidence." Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats 23.2 (1991): 234-41.

- Burrows, John. “Computers and the Idea of Authorship.” The Humanities and a Creative Nation: Jubilee Essays. Ed. Deryck M. Schreuder. Canberra: Australian Academy of the Humanities, 1995.

- Burrows, John. “All the Way Through: Testing for Authorship in Different Frequency Strata.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 22 (2007), 27-47.

- Burrows, John, and Hugh Craig. "Lucy Hutchinson and the Authorship of Two Seventeenth Century Poems: A Computational Approach." The Seventeenth Century 16 (2001): 259-82.

- Chatfield, Christopher, and Alexander J. Collins. Introduction to Multivariate Analysis. London: Chapman and Hall, 1989.

- Cox, John D., and Eric Rasmussen. Introduction. King Henry VI Part 3. The Arden Shakespeare (Third Series). London: Thomson Learning, 2001. 1-176.

- Craig, Hugh. "Is the Author Really Dead? An Empirical Study of Authorship in English Renaissance Drama." Empirical Studies in the Arts 18.2 (2000): 119-34.

- de Grazia, Margreta, and Peter Stallybrass. "The Materiality of the Shakespearean Text." Shakespeare Quarterly 14.3 (1993): 255-83.

- Forsyth, R S, D I Holmes, and Emily Tse. "Cicero, Sigonio, and Burrows: Investigating the Authenticity of the Consolatio." Literary and Linguistic Computing 14 (1999): 375-400.

- Garrard, Peter. “Cognitive Archaeology: Uses, Methods, and Results." Journal of Neurolinguistics 22.3 (2009): 250-65.

- Grosz, Elizabeth. Space, Time and Perversion: The Politics of Bodies. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Hirst, Graham, and Ian Lancashire. “Vocabulary Changes in Agatha Christie’s Mysteries as an Indication of Dementia: A Case Study.” Poster presented at the 19th Annual Rotman Research Institute Conference, “Cognitive Aging: Research and Practice,” Toronto, 2009. 18 August 2009. <http://ftp.cs.toronto.edu/pub/gh/Lancashire+Hirst-extabs-2009.pdf>.

- Holderness, Graham. Textual Shakespeare: Writing and the Word. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2003.

- Holderness, Graham, and Bryan Loughrey. Introduction. A Pleasant Conceited Historie, Called the Taming of a Shrew. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1992. 13-36.

- Hoover, David L. "The End of the Irrelevant Text: Electronic Texts, Linguistics, and Literary Theory." Digital Humanities Quarterly 1.2 (2007). Online at <http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/001/2/000012.html>.

- Hope, Jonathan and Michael Witmore. "The Very Large Textual Object: A Prosthetic Reading of Shakespeare." Early Modern Literary Studies 9.3 (2004): 6.1-36 <http://purl.oclc.org/emls/09-3/hopewhit.htm>.

- Jackson, MacDonald P. "Early Modern Authorship: Canons and Chronologies." Thomas Middleton and Early Modern Textual Culture: A Companion to the Collected Works. Ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007. 80-97.

- Jowett, John. "Measure for Measure: A Genetic Text." Thomas Middleton and Early Modern Textual Culture: A Companion to the Collected Works. Ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007. 681-9.

- Knapp, Jeffrey. "What Is a Co-Author?" Representations 89 (2005): 1-29.

- Lancashire, Ian. "Empirically Determining Shakespeare's Idiolect." Shakespeare Studies 25 (1997): 171-85.

- Liberman, Alexander. The Artist in His Studio. Rev. Ed. New York: Random House, 1988.

- Love, Harold. Attributing Authorship: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Masten, Jeremy. Textual Intercourse: Collaboration , Authorship and Sexualities in Renaissance Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Merriam, Thomas. "Linguistic Computing in the Shadow of Postmodernism." Literary and Linguistic Computing 17.2 (2002): 181-92.

- McMullan, Gordon. The Politics of Unease in the Plays of John Fletcher. Amherst: University of Amherst Press, 1994.

- McMullan, Gordon. "'Our Whole Life Is Like a Play': Collaboration and the Problem of Editing." Textus 9 (1996): 437-60.

- McMullan, Gordon, ed. King Henry VIII (All is True). By William Shakespeare and John Fletcher. The Arden Shakespeare, third series. London: Thomson Learning, 2000.

- McMullan, Gordon. Shakespeare and the Idea of Late Writing: Authorship in the Proximity of Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Mosteller, Frederick, and David L. Wallace. Inference and Disputed Authorship: The Federalist. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1964.

- Pinker, Steven. The Language Instinct. London: Penguin, 1994.

- Spedding, James. "Who Wrote Henry VIII?" Gentleman's Magazine 178 / new series 34 (1850): 115-23.

- Vickers, Brian. Appropriating Shakespeare: Contemporary Critical Quarrels. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Vickers, Brian. "Incomplete Shakespeare: Or, Denying Coauthorship in 1 Henry VI." Shakespeare Quarterly 58.3 (2007): 311-52.

- Vickers, Brian. Review of William Shakespeare, King Henry VIII, or All Is True, ed. Jay L. Halio, World's Classics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999) and William Shakespeare and John Fletcher, King Henry VIII, ed. Gordon McMullan, the Arden Shakespeare (London: Thomson Learning, 2000). Review of English Studies 53 (2002): 119-25.

- Vickers, Brian. Shakespeare, Co-Author: A Historical Study of the Five Collaborative Plays. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

- Wells, Stanley, and Gary Taylor, with John Jowett and William Montgomery. William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987.