Lancelot Andrewes's 'Orphan Lectures': The Exeter Manuscript

[1]

P.G. Stanwood

University of British Columbia

stap@shaw.ca

Peter McCullough

Lincoln College, Oxford

Peter.McCullough@lincoln.oxford.ac.uk

Ray Siemens

University of Victoria

siemens@uvic.ca

P. G. Stanwood, Peter McCullough, Ray Siemens, and others. "Lancelot Andrewes's 'Orphan Lectures': The Exeter Manuscript". Early Modern Literary Studies Texts Series 2 <URL:http://purl.org/emls/andrewes/andrewes4.htm>.

Contents

- Introduction (P. G. Stanwood)

- Bibliographical Descriptions (Peter McCullough): Lancelot Andrewes, Apospasmatia Sacra (1657)

- A Digital Facsimile of the Newly-discovered Exeter Manuscript of Lancelot Andrewes (Ray Siemens, with Karin Armstrong, Gerry Watson, Mike Elkink, and Greg Newton; 276 pp.)

- Apospasmatia sacra, or, A collection of posthumous and orphan lectures (An external link to the EEBO 1657 text, Wing / A3125)

- Transcriptions

(P. G. Stanwood):

- On the Transcriptions

- Selection 1. The lecture on Revelation 2.7 (Notes by Peter McCullough) Selection 2. 1. Gen. 11.

- Selection 3. Gen. 3.16.

- Selection 1. The lecture on Revelation 2.7 (Notes by Peter McCullough)

- Selection 2. 1. Gen. 11.

- Selection 3. Gen. 3.16.

1. Introduction

There has recently come to light an early seventeenth-century manuscript of Lancelot Andrewes’s Apospasmatia SACRA: or A Collection of posthumous and orphan lectures. [2] For the first and only time published in 1657—some thirty years after Andrewes’s death in 1626—their authorial integrity has ever since been in doubt. In a hastily contrived preface, the notable Laudian Thomas Pierce declared ‘that this Volumne of Notes was only taken by the Eare from the voluble Tongue of the Dictator, as he deliver’d them out of the Pulpit; and so are infinitely short of their original perfection’. Pierce continues painstakingly to discredit these ‘Notes’, which, had he been consulted, would not have appeared. In reflecting and extending this judgement, James Bliss rejects the ‘Orphan Lectures’ for inclusion in the eleven volume edition of Andrewes’s Works in The Library of Anglo-Catholic Theology, noting that ‘there does not appear to be sufficient evidence to justify one in ascribing these sermons, at least in their present form, to Bishop Andrewes’. [3] Thus this substantial body of work, comprising of over 700 octavo pages, has remained marginal to most students of Andrewes. [4]

In recounting the early years of Andrewes’s life, Henry Isaacson, his amanuensis and biographer, declares ‘that in S. Paul’s Church … he read the lecture thrice a-week in the term time’ besides often preaching at St Giles’. [5] The only record that we have had until now of these lectures and sermons is provided by the ‘Orphan Lectures’, a systematic study and exegesis of the first four chapters of Genesis, verse by verse, as well as a number of homilies on various other texts from both Old and New Testaments. Most of these exegetical or homiletic sections are extensive, carefully wrought, fully coherent, and entirely characteristic of Andrewes’s unmistakable style. The notion that any of them might have been the notes of an auditor is most improbable, though one might accept the possibility that Andrewes considered expanding or revising them. [6]

The manuscript of the ‘Orphan Lectures’ that I have

examined gives unique testimony to the authenticity of this work and firmly

corroborates its authorial integrity. Now privately held in

The second of these loose leaves gives a fuller statement by Daniel Hollingworth, in his hand: ‘To my Deare beloued Mr John / Chomely the younger my young Nephew / Sir Paule Pinder that was Ambassader / Near xx years in Turkey famose in the / Turkish History had and [Bouand?] this book And / Docter Hacket of St Andrewes in Holdborne hath / Tould mee, Neuer a Devine in England / Could Capp: Sir Paule Pinder in purest Christianitie / And he with his owne hands gaue to the / poure & to Hospitalls & to Churches & / Bulding of Paules in his owne dayes with his owne hands / Fortie Thousand Pounds And had noe / Pictshure in his house But the Pictshure / of Docter Andrewes And hath oft sayd / To mee, That since St Pauls dayes / The Church of God had Neuer / his Fellow. // soe say I think.’ Hollingworth’s name appears below this inscription, but in the hand perhaps of the recipient, who glosses the proper names ‘Hacket’, ‘Andrews’, and ‘Pindar’, quoting from Treatise of Temples, 1638, chap. 25. [8]

One may reasonably

presume that ‘this book’ refers to the manuscript that Hollingworth was giving

to his nephew. This single loose leaf might once have been part, not of the

present manuscript, but of one that now survives only in four pages (or the two

leaves of one folio sheet) of prefatory matter which must have been copied much

later—perhaps mid-century—from the principal manuscript under discussion, or

else another like it (see plate 1).

The reference to Pindar’s having been already in

The Exeter

Manuscript begins with folio 2r, the first folio sheet in fact being the one

that contains the earliest inscription, ‘Doctor Andrewes Sermons …’ that forms

the paste-down on the inside of the front cover, that is, folio 1r, and with

the pencilled date ‘1598[?99]’ on the verso. The leaf in Hollingworth’s hand

that describes Sir Paul Pindar’s ownership of the Exeter Manuscript might have

become detached and offered as a preliminary leaf to a second manuscript, now

lost, that includes only four prefatory pages. The surviving pages (of this one

folio sheet) still retain fragments in the gutter of the binding thread.

Certainly we do have what seems to be the beginning of a second manuscript; the

hand is obviously much later than that of

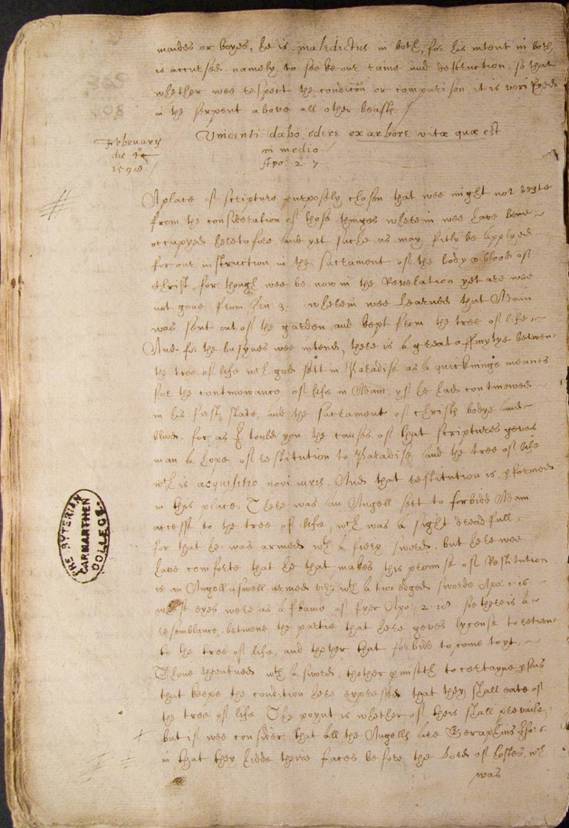

Measurements of the Exeter Manuscript (and also of the single loose leaf) are 290 x 195 mm. (pot folio). There are 276 folios; the final one, folio 276r is a paste-down on the end cover. Five leaves have been cut out at 243v–244r. The gatherings are bound up variously, in six, seven, or often nine folio sheets. At the beginning of the manuscript are the lectures at St Paul’s, from f. 2r to 228r; 228v is blank; a different scribe begins at f. 229r, with the earlier lectures at St Giles’, and with some repetition of material that has appeared earlier in the manuscript. Compared with the printed text of 1657, the Exeter Manuscript employs throughout orthography and scribal forms of the earlier seventeenth century. There are numerous variants, chiefly of an accidental rather than a substantive kind; but several sections are unique to this manuscript, or else greatly altered in the printing. Notable amongst these sections is Andrewes’s sermon on the Apocalypse, misplaced in 1657, but remarkable for its author’s discussion of eucharistic doctrine (see plate 3).

plate 1. The opening page of the loose leaf

accompanying the

plate 2. Watermark of the loose leaf accompanying the

plate 3. Folio 146v of the

COMPARISON WITH THE PRINTED VERSION

The relationship of manuscript to printed text is complicated, but the following comparison of the two indicates principal differences.

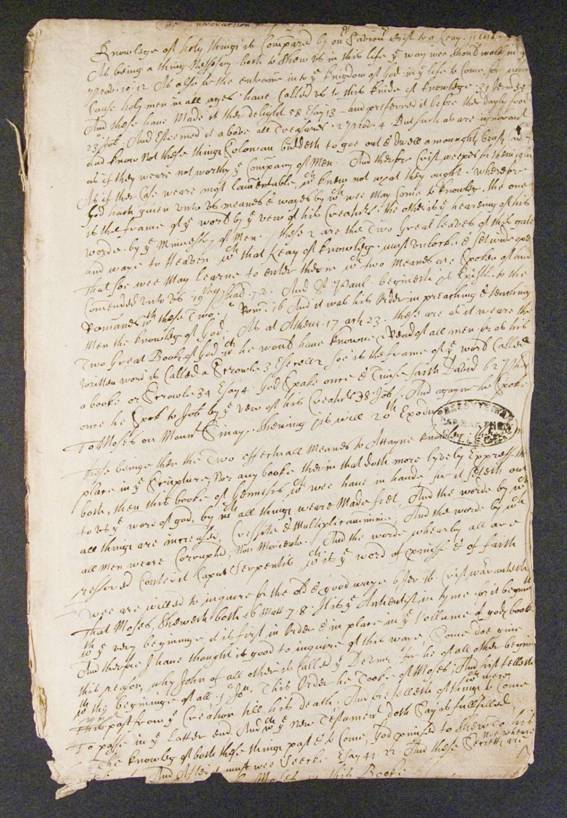

The manuscript opens with ‘Knowledge

of holy things is Compared by our Saviour Christ to a Keay’, which appears in

the Addenda of 1657 (pp. 657 ff.), ff. 2r–v. Then follow the lectures on

Genesis, preached at

Gen. 1.1–11 3r–37r

12 37r–v

14 37v–38v

16–30 38v–48r

Manuscript and printed text are very different from verse 12 on. There is no manuscript text for verses 13, 15, or 31; but 1657 continues the sequence from verses 12–31 without interruption.

Gen. 2 begins at 48r.

1–19 48r–107r

21–24 107r–114v

Gen. 2.20 is missing from the manuscript, which continues with Gen. 2.21 through 2.24, where this section ends; but 1657 continues through verse 25, that is, the end of chap. 2.

Gen 3.1–5 114v–125v

6 Omitted from the ms

7 125v–128r

8–14 128r–146v

Apoc. 2.7 146v–150v

The date ‘9.Aug:1620./’ appears in the margin of 128r, at the beginning of the lecture on Gen. 3.8, in a hand different from that of the scribe, but contemporary with it. At this point, the manuscript ends Gen. 3 with verse 14 (ff. 141r–146v); however, it then gives Andrewes’s lecture on Revelation 2.7 (ff. 146v–150v), which 1657 removes to the concluding section of homilies ‘preached upon severall choice Texts’ (pp. 572–8). Now 1657 continues to the end of Gen. 3 (that is, verse 24). And ff. 229r–276r, in the hand of a different but contemporary scribe, complete these verses of Gen. 3, beginning with (and repeating the discussion of) verse 14.

Gen. 4.1–26 150v–228r The lower half of 228r is blank; 228v is also blank.

This section of the manuscript is very carefully copied, and the printed text follows it closely, but with many accidental variants. Also, the verse headings are all from the Vulgate; earlier sections are inconsistent in this usage.

The manuscript continues with 229r, in a different but similar hand, and concludes at 276r.

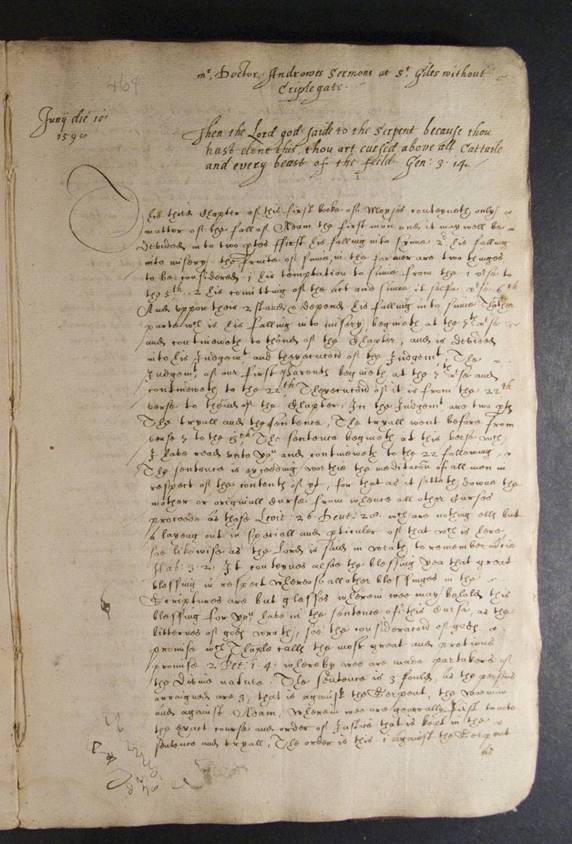

Folio 229r is headed: ‘Mr. Doctor Andrewes Sermons at St. Giles without Criplegate.’ (see plates 4 and 5)

Gen. 3.14[1] 229r–234r [in margin: ‘Junij die 18 1598’]

The copy is identical with ff. 141r–146v, the first part of Gen. 3.4: ‘Then the Lord god saide to the serpent because thou hast done this thou art cursed above all Cattaile and every beast of the feild.’

Gen. 3.14[2] 234v–239r [in margin: ‘Junij die 25 1598’]

The second part of the verse, appearing also in 1657: ‘Uppon thy belly shalt thou goe and dust shalt thou eate all the dayes of thy life.’

Gen. 3.15[1] 239r–243v [in margin: ‘Julij die 2o. 1598’] ‘I will alsoe putt enmitye betwene thee and the woeman and betwene her seede and thy seede.’ [In 1657]

Gen. 3.15[2] 243v–246v [in margin: ‘Aug. 20. 1598’]

The second part of the verse, appearing also in 1657: ‘He shall breake thyne head, and thou shalt bruise his heele.’ [The lectures for Gen. 3.14 and 15 have been detached from the regular sequence in 1657, and misplaced at the end of the volume. Five leaves have been cut out from the manuscript between 243v and 244r; only a few lines on Gen. 3.15 remain at the bottom of 243v, but a substantial portion of what may belong to the lecture on Gen. 3.16 remains as 244r–246v.

Gen. 3.16 ‘Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.’ (KJV).

What remains of this lecture, which is decidedly about the scriptural text, is quite different from what occurs in 1657. Andrewes writes with expansive vigour, in a fashion reminiscent of his lecture on Gen. 2.18, about the creation of Eve.

Gen. 3.17–24 246v–276r

Apart from conventions of orthography and punctuation, the printed text follows the manuscript closely. Yet 1657 would seem to have been set from a different manuscript (or several manuscripts?).

plate 4. Folio 229r of the

plate 5. Watermark of fol. 228r, the paper stock common to the entire bound volume (Original paper size 290 x 195 mm.) Reproduced by permission of Professor Ivan Roots.

CONCLUSION

The existence of the Exeter Manuscript, a volume, which, as we have seen, contained two different though contemporaneous versions of the ‘Orphan Lectures’, as well as the fragment of still another manuscript in yet a further and third hand, suggests that more manuscripts may yet come to light; for Andrewes’s lectures and sermons of his early career must have enjoyed some circulation—how widely we cannot, of course, know. Of interest also is the fact that 1657 is incomplete, obviously hastily compiled from a manuscript (or manuscripts) that were conveniently at hand, or readily available to Thomas Pierce and such loyal printers as Moseley and Royston. Yet in missing or confusing the sections that do appear in the Exeter Manuscript, the printers cause one to query how else they might have been misled. The sermon on Revelation 2.7, for example, is especially significant; for in it Andrewes is developing his ‘high’ view of the eucharist with considerations ‘suche as may fitly be applied for instruction in the sacrament of the body & blood of Christ’, [9] yet the sermon is relegated to the miscellaneous section following the discourses on Genesis (beginning at p. 515). Clearly, a new edition of the ‘Orphan Lectures’ is needed that will bring together all the material that we now possess. Such an edition should allow full comparison of manuscript to printed text and thus help also to illuminate Andrewes’s own practises of composition and doctrinal belief. [10]

2. Bibliographical Descriptions (Peter McCullough): Lancelot Andrewes, Apospasmatia Sacra (1657)

COPY 1. Union Theological Seminary (EEBO; UMI Wing

303:1).

Title. [within double rules] APOSPASMATIA SACRA: | or | A Collection of posthumous and orphan | LECTURES:|

Delivered at St. Pauls and St. Giles his Church, | BY | The Right

Honourable | AND | Reverend Father in God | LANCELOT ANDREWS,

| Lord Bishop of VVinchester. | [rule] | Never before extant. | [rule] |

Apothanon eti laleitai Heb. 11.4. | [rule] | [device:

shield with coat of arms of Cambridge Univ.; cf. McKerrow 399] | [rule]

| LONDON, | Printed by R. Hodgkinsonne, for H. Moseley, A.

Crooke, | D. Pakeman, L. Fawne, R. Royston, and N.

Ekins. 1657.

Formula. 2o in

4s: )(4 2)(4 3)(4 4)(2 b-d4 A-Z4 2A-2Z4 3A-3P4 3Q-3S2 3T-3Z4 4A-4S4; [$3 signed (- )(1, 4)(2,

d3, P1, 2H3, 2Z1, 3Q2, 3R2, 3S2; 2O1 signed ‘O’)]; 367 leaves, pp. i-lii

1-111 112-114 115-245 246-248 249-312 305-351 352-354

363-499 500-502 515-694 (misprinting 7 as ‘6’, 131 as ‘132’, 265 as

‘272’, 266 as ‘247’, 271 as ‘251’, 272 as ‘265’ , 323 as ‘326’, 326 as ‘323’,

454 as ‘445’, 613 as ‘413’

Paper. (microfilm)

Types. (microfilm)

Contents. )(1, title (verso blank); )(2, The Preface; b1 Elenchus Latino-Anglus Omnium Concionum

totius Libri; Numerus paginam indicat. . . . Index Concionum in Caput Primum

Geneseôs; b3v Index

Concionum in Caput Secundum Geneseôs;

c1 Index Concionum in Caput Tertium Geneseôs c3 Index Concionum in Caput Quartum

Geneseôs; d1 Index Concionum

diversarum, ex veteri et novo Testamento;

d4 Lectures Preached upon the first chapter of Genesis (half title;

verso blank); A1 Lectures, Preached at

Saint Paules London; P1 Lectures

Preached upon the Second Chapter of Genesis (half title; verso blank); P2 Lectures preached in Saint Pauls Church

London; 2H4 Lectures Preached upon the

Third Chapter of Genesis (half title; verso blank); 2I Lectures.

Preached in Saint Pauls Church, London;

2R1 Lectures Preached in the Parish Church of St Giles without Cripplegate,

London; 2Z1 Lectures Preached upon the

fourth Chapter of Genesis (half title; verso blank); 2Z2 Lectures Preached in the Parish Church of

St Giles without Cripplegate London; 3T1

Lectures Preached upon Several choice Texts, both out of the Old and New

Testament (half title; verso blank); 3T2

Lectures Preached in the Parish Church of St Giles without Cripplegate

London; 4O1 Addenda;

on 4S3v ‘FINIS’

Running Titles. )(2v – 4)(2v The Preface; b1v – d3 Index Capitum

A1v – O4, P2v – 2H3, 2I1v – 2Q4v,

Lectures preached in St. Pauls Church.; 2r1v – 2Y4, 2Z2v

– 3S2 Lectures preached in St. Giles’s Church | without Cripplegate;

3T2v – 4N4 Lectures preached in St. Giles’s Church | without

Cripple-gate 4N4v Lectures

preached in St. Giles’s Church, &c. 4O1v

– 4P4 Lectures preached in

Catchwords. 2f2 ‘Of’ ‘De’ 2N3 ‘offend’ ‘offended’ 2P4v ‘An’ ‘Another’ 2X4v ‘than’ ‘then’ 3B4v ‘an’ ‘and’ 3E2 ‘eth’ ‘teth’ 3O1 ‘Lamech’ ‘Assumpsit’ 3Q2 ‘Socondly,’ ‘Secondly,’ 4D1 ‘Sacra-’ ‘Sacrament’ 4D4 ‘ter,’ ‘ter.’ 4E2v ‘the’ ‘of’ 4E4v ‘there-’ ‘therefore’ 4G2v ‘chapter,’ ‘chapter.’ 4L1v ‘the’ ‘for’

Notes. On balance, not a substandard piece of

printing. The impression of sloppiness

derives mostly from the copy text and lack of editorial intervention before its

typesetting. Signatures are sequent and

catchwords reliable, with only a few exceptions to the latter. Most egregious printer’s fault is in

pagination. Detailed marginal

instructions to ‘insert’ sermons from ‘Addenda’ elsewhere in sequence are

clearly for readers, not setters.

Preface and Index set together, after the setting of the main body (cf.

how index integrates and rationalises the ‘Addenda’ texts with those in the main

run); since Preface and Index set last and use the faulty pagination, highly

unlikely that any copies would have a corrected run of pagination (this would

render index unusable). That the

‘Addenda’ texts begin with a new gathering (4O) might further suggest that they

derive from an MS copy text independent of that of the main run of

lectures/sermons (note also that in addition to supplying texts not in the main

run, they also include dates not found in main run).

1. Eyre, Rivington and Plomer, eds., A

Transcription of the Registers of the . . . Company of Stationers from 1640 –

1708, vol. II, p. 20:

‘27 Novemb[er] 1655. M[aster] Richard Hodgkinson Entred (under the

hand of Master NORTON Warden) a booke called fourty lectures preached in St

Pauls Church upon the first, second, third & fourth chap. of GENESIS; and

fourty five lectures preached in the parish church of St Giles, Cripplegate

upon severall texts, by Lancelot Andrews, DD, late Bp of Winchester’. NB how drastically this differs from text as

printed (98 lectures on Genesis 1-4, 25 lectures on ‘other texts’; however, if

the 9 Genesis lectures contained in the ‘Addenda’ are placed with the ‘upon

severall texts’ group here, the numbers would be 89 and 34 - ?; OR if the

printed texts are divided by place of preaching, count = 71 at St Paul’s, 33 at

St Giles). NB how Register entry places all

Genesis lectures ‘in

2. )(1 autograph ‘Jos: Glanville | pretiu[m].

11s.’ Joseph Glanvill (1636-1680),

theologian and Anglican controversialist; BA Exeter College Oxford 1655, migr.

to

3. passim many MS emendations (by

Glanvill?) correcting egregious typesetting errors.

4. Title Page.

Graeco-Latin title = ‘Holy Fragments’.

Greek epigram (Heb. 11.4) = ‘he being dead yet speaketh’. Coat of arms (Cambridge University); used by

Hodgkinson for at least one other publication by a Cambridge-educated author

(Henry Spelman, Villare Anglicum, 1656); Hodgkinson used arms of Oxford

for publications by Oxonian Robert Vilvain; Hodgkinson seems not to have used a

device of his own in any of his publications.

5. Formula.

NB: disturbance in pagination

coincides with shift within lectures on Genesis 3 from

6. Catchwords.

Formula here gives catchword as given on stated fol. followed by word in

text following. Slippage on 2f2 and 3O1

from English to Latin (both instances being catchwords linked to Biblical texts

given at new sermon headings) might suggest that MS copy text had Biblical

texts in both English and Latin, whereas only Latin was set (as an economy?).

7. NB:

UMI photographer (presumably confused by disturbance in typesetters’

pagination) duplicates several leaves in 2S and 2U.

COPY 2.

Title. as Copy 1.

Formula. as Copy 1, EXCEPT: 2X2 signed ‘X2’; pg. 613 is ‘613’

Paper. Mix of two watermarks: 1. pot with initials ‘PH’; 2. shield within a

double circle, bend, initials (?) in dexter chief. Chainlines vertical (confirming folio).

Type. body 88.

face 80x2:3 = pica roman. This

for the overwhelming majority of type set.

Some italic and greek; brevier for marginalia. Type, format, etc. does not change throughout

body of main text, suggesting all set in Hodgkinson’s shop.

Ornaments. )(2 block orn (100 x 31mm), crowned royal

arms with garter supported by crowned lion (l) and unicorn (r) surrounded by

thistles and Tudor roses (largest crowned);

A1 block orn (82 x 39mm), naked female bust w/ outstretched arms flanked

by (West Indian? African?) naked women seated with cornucopias; passim range of modest orn. block

capitals, ca. 30x30mm; half-title pages without orn.

Notes. Two variants in formula between Copies 1

& 2 confirm that there were minor press-corrections during run. A clean copy with no contemporary marginalia

or marks (except succession of 3 Bodleian shelfmarks on front pastedown); a

modern hand corrects pagination in pencil.

Front board (not contemporary) detached.

COPY 3. Queen’s College,

Title. as Copy 1.

Formula. as Copy 1, EXCEPT: 2O1 signed correctly (‘Oo’); 3T1 not signed;

p. 266 correct (‘266’); p. 271 correct (‘271’).

3S4 is integral (not pasted-down)

Paper. as Copy 1.

Type. as Copy 1.

Ornaments. as Copy 1.

Notes. Further incidental variants in formula

between both Copy 1 and Copy 2 confirm further minor press-corrections.

1. Contemporary calf binding, front board almost

detached. Front paste-down has small

(C19) label pasted-in: ‘C.J. Stewart /

2. Endpapers visible: facing )(A1 C17 printed text (‘Jezabel swore

by her gods, and is eaten by’; ‘house, lest thou be an accursed thing like

it; but shalt be utterly de-’.

3. )(1 ms inscription: ‘Tho: Charles 1789’ (1755-1814; Welsh

Calvinistic Methodist preacher; author of Welsh Bible transs. and catechisms; ODNB). In the same hand (?) some underlining pp.

207-8; large hand-pointer to 1st new para., p. 351. Otherwise a clean copy.

4. Transcriptions (P.G. Stanwood)

Contents

I have transcribed these selections from the Exeter Manuscript with near diplomatic care. Punctuation is preserved (or its lack), as well as capitalisation, though I confront the familiar difficulty of distinguishing between majuscule and miniscule forms of such letters as L / l and C /c. I make no attempt to alter the accidentals and spelling, and have retained u and v, i and j, though the scribal copy itself is very inconsistent in distinguishing between them. I retain most superscript forms of which, yet, with, ye, our, and retain the ampersand; but I expand the common scribal abbreviations for per and pro, the tilde, and Latin abbreviations. The scribe uses italic or a mixture of italic and secretary for citations and references, with the verses cited at the beginning of each section generally in italic. I have given all such citations in italic, both at the head of each section and within the subsequent body of discussion. Most, but not all proper names appear in italic, and in this point I have attempted to follow whatever the text seems to show.

Many statements run on, or are fragments; but I have not attempted any change except occasionally where great confusion might occur. In these instances, I have used square brackets to call attention to an editorial insertion. Many statements appear half formulated and sometimes there are blank spaces where whole phrases or words are missing— sometimes these gaps are noted with a + mark in the margin. The scriptural citations, which may be by verse, book, and chapter, or else by chapter, book, and verse, usually come from the Geneva Bible, or else from the Vulgate, but I have not altered incomplete or inaccurate references. A curious feature of the manuscript is the series of hatchmarks in the margins of ff. 37r through40v (e.g. /// ). Usually, one sees two such marks together, but there may be as many as six. Their significance is not clear, but they would seem perhaps to indicate some kind of collation with other manuscripts or witnesses.

Andrewes like many of his contemporaries turned especially to Genesis

for extended exegetical reflections, but his comments have been largely

overlooked—a notable omission, for example, in Arnold Williams’s Common

Expositor: An Account of the Commentaries on Genesis 1527–1633 (Chapel Hill:

University of North Carolina P, 1948). The three selections here are chosen in order

to illustrate Andrewes’s unique style and purpose as well as to show different

features of the manuscript in comparison with the printed text.

Selection 1. The lecture on Revelation 2.7. This text essentially appears in 1657, pp. 572 – 78,

not in sequence with the considerations of Genesis as in the manuscript, but in

a concluding section of homilies on various texts. See XCVI Sermons, Easter 2 (1607, 1

Cor. 15.20): The text’s ‘first fruits of

the dead’ means that an agricultural metaphor runs throughout the sermon, and

it blends with a eucharistic peroration perfectly: ‘Such was the meanes of our

death, by eating the forbidden fruit, the first fruits of death: and such is

the meanes of our life, by eating the flesh of

CHRIST, the first fruits of life’ (5th ed. London, 1661, p.

262). In this ‘lecture’, Andrewes

develops the typology of the Tree of Life as a restorative means of grace (cf. Faerie

Queene, I.ii.30, and the story of Fradubio / Fraelissa — who become a tree

whose branches, when broken, bleed).

See esp. Peter McCullough, ed., Lancelot Andrewes: Selected

Sermons and Lectures (

This edited version is by Peter McCullough.

Text. Exeter Manuscript (hereafter EM), fols. 146v – 150v, collated with Apospasmatia Sacra (1657, hereafter AS), pp. 572-578. All variants, some of which are substantive, are recorded in the apparatus. The number of readings from AS which clarify, correct, or improve the sense suggests some combination of ‘tidying’ by the editor or compositor of AS, and the likely superiority of the (lost) copy for the latter over EM. Copy for EM and AS is shown (from other sermons collated) to be different, though not necessarily unrelated, since both contain common errors (a good example of which is the incorrect citation – certainly by transcription error in an anterior copy common to both -- of John 14 for John 1.4, below p. 6, line 7).

Headnote. The sermon edited here is part of a

remarkable survival, perhaps unique for 1590’s London: extensive notes of a single minister’s

complete parish preaching rota stretching over many months (‘notes’ is perhaps

slightly misleading – these are summaries written in continuous prose, much

fuller than the outline notes often encountered in commonplace books of the

period). The bulk of the sermons in

question are Andrewes’s lectures on Genesis 3.14-24 and all of Genesis 4. These were preached between Sunday, 18 June

1598 and Saturday, 17 February 1599 at St Giles’s Cripplegate (a sprawling

parish immediately north of

Taken together, the evidence of these lectures and other sermons suggests that Andrewes preached, during term time, two to three afternoon lectures in St Giles per week, as well as twice a month in the morning, one of the latter of which being a monthly Sunday communion. With such different aims (the systematic exposition of a book of the Bible in the Genesis lectures, vs the application of a text proper to a feast day or holy communion), these two parts of Andrewes’s preaching rota rarely intersected. A prominent exception, however, is the sermon presented here, which opens by self-consciously announcing itself as a communion day sermon based on a text related to the portion of Genesis recently treated in the independent lecture series: on the two preceding Sundays (21, 28 January 1599) the Genesis series had considered Genesis 3.23 and 3.24 – the story of the ‘Tree of Life’ planted in the Garden of Eden – and then, at the communion on Sunday 4 February, Andrewes chose as his text the New Testament vision of the ‘Tree of Life’ in heaven (Rev. 2.7).

The sermon is in itself valuable as a relatively rare example of a

sermon expounding the eucharist at a routine Sunday parish observance. Among Andrewes’s surviving works, it is

further significant as a parochial example of the far grander feast day

eucharistic sermons preached at the court of James VI & I, which so

dominate the authorized edition XCVI Sermons (1629, commissioned by

Charles I and edited by William Laud and John Buckeridge). But this, and the other eucharistic sermons from

AS, have even greater significance as some of the earliest examples of

Andrewes’s ‘avant-garde conformity’, the hallmarks of which are an elevated

view of the efficacy and importance of the sacraments and a sustained critique

of English Calvinist predestinarianism.

As notes (presumably taken by a listener, though possibly derived from

authorial notes or drafts), these sermons lack both the literary finesse and

the scholarly apparatus of those sermons which Andrewes painstakingly prepared

for print in his own lifetime or which appeared in XCVI Sermons. But in addition to thought, arguments, and

structures immediately recognizable as Andrewesian, there also survives

Andrewes’s characteristically sophisticated mode of composition using

tight-knit tissues of scriptural quotation, something that is perhaps even

exaggerated here in the condensed summary form of the notes.

Content & Sources. Andrewes’s exegesis of Rev. 2.7 is best

summarized by placing it in the context of other influential commentary (both patristic

and early modern) on its dominant image, the ‘Tree of Life’. Interpretation of the tree (and its fruit) as

a sacrament has a long pedigree, dating at least from Augustine’s De

Civitate Dei, xiii.20. There, considering the state of Adam and Eve’s

natural bodies before the Fall, Augustine explained that though not subject to

death, their ‘animal’ bodies required ‘nourishment’. Hence, they ate of the many fruits of the

garden for natural purposes, but their bodies were preserved from natural decay

by the power of the Tree of Life. In his

summary, ‘other fruits were, so to speak, their nourishment, but this [the Tree

of Life] their sacrament’ (The City of God, trans. Marcus Dods, New

York, 1950, p. 431). After Augustine,

exegetical and doctrinal debates ebbed around whether Adam and Eve actually ate

of the Tree of Life, or whether it simply exuded a preservative power; and

about whether that power was natural (like a medicine), or divine (grace). Typically, Andrewes here skirts the

quiddities of means, and focusses only on effects: ‘that was a naturall tree appoynted to

preserve

Exegetical tradition agreed that the heavenly Tree of Life promised to

the faithful in Revelation 2.7 (Andrewes’s text here) was the heavenly cognate

of the Edenic tree of the same name in Genesis.

Several of Andrewes’s contemporaries therefore discussed the sacramental

nature of the Tree of Life, whether in

Against this broadly Augustinian and Calvinist consensus, Andrewes’s

exegesis stands out in bold relief. To

begin with, Andrewes’s English contemporaries were skittish about extending

Augustine’s sacramental reading of the tree to the eucharist (Fulke’s rejection

of precisely such a reading by Sanders being the exception which proves the

rule). Although Fulke and Perkins

discuss the tree as a sacrament or symbol of Christ’s gift of eternal life

generally, they do so only by discussing the tree historically (in Genesis), or

anagogically (in Revelation). Missing

from their commentaries is precisely what Andrewes adds, that is, a reading of

the Tree of Life as an image with a tropological (earthly) referent: the eucharist. The identification is swift, emphatic, and

repeated, first in the opening sentences (1.3-6) where the tree ‘may fitly be

applyed’ to communion. The strategy ‘to

applye this scripture to our present purpose’ (2.11) is next repeated with the

added force of linking the tree and communion explicitly to the most climactic

eucharistic passage in the New Testament, the sixth chapter of John’s

gospel. Andrewes even paraphrases the

most provocative verse (57, at 2.15: ‘my flesh is that bread . . . soe he that

eateth me shall live by me’), before rattling-off a conflating sequence of

imagery for the eucharist: ‘fuite of the

tree . . . bread of life . . . Manna . . . Christes body and blood’

(2.16-19). Andrewes’s embrace of the

Johannine insistence on literal eating, on physical reception, is what

distinguishes him here from contemporary Calvinists. Perkins, for example, glosses the same phrase

‘To eate of the tree’ (Rev. 2.7) also with a verse from John (6.50,

‘This is that breade, which commeth downe from heauen, that hee which eateth of

it, shoulde not die.’), but with the swift and crucial caveat that ‘to eate

signifieth sometime to believe’.

Therefore, both John 6 and Rev. 2.7 give priority to the spiritual sense

of eating as believing in Christ, rather than the physical sense of

eating as receiving Christ: ‘for he which truly beleeueth in Christ, he

is a partaker of Christ’ (Perkins, Lectures, pp. 161-2).

It is certainly not the case that Calvinists like Perkins and Fulke held

belief necessary for the efficacy of the eucharist while Andrewes did not. Nor is it true that Perkins and Fulke

dismissed the necessity of receiving the sacraments. The crucial difference is one of emphasis

which contains within it, for Andrewes, greater claims for the operative

efficacy of communion, something which becomes very clear in the latter parts

of the sermon. The eucharist fades from

the sermon while Andrewes discusses the heavenly

Further

In addition to the works cited above, see, for an overview of Andrewes’s

‘avant-garde conformity’ Peter Lake, ‘Lancelot Andrewes, John Buckeridge and Avant-Garde

Conformity at the Court of James I’, in Linda Levy Peck, ed., The Mental

World of the Jacobean Court (Cambridge, 1991), pp. 113-33; the discussion

is helpfully extended to the Elizabethan period by Nicholas Tyacke, ‘Lancelot

Andrewes and the Myth of Anglicanism’, in Lake and Michael Questier, eds., Conformity

and Orthodoxy in the English Church, c. 1560-1660 (Cambridge, 2000), pp.

5-33. Outlines of major English

positions on eucharistic theology are Brian Spinks, Two Faces of Elizabethan

Anglican Theology: Sacraments and Salvation in the Thought of William Perkins

and Richard Hooker (London, 1999), and Sacraments, Ceremonies, and the

Stuart Divines (Aldershot, 2002).

Andrewes’s sermon may also bring fresh life to a long-lived discussion

in studies of Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene: the interpretation of the ‘goodly tree . . .

the tree of life’ (I.xi.46.1, 9)

which restores Red Crosse Knight during his climactic battle with the dragon

(I.xi.46-52). Rosemund Tuve’s trenchant warning not to

limit the allegorical signification of Spenser’s Tree of Life to only the

eucharist is salutary (Allegorical Imagery, Princeton, 1966, pp.

110-12). But in that episode, Spenser

does seem to share Andrewes’s view of the Tree of Life as simultaneously both a

symbolic pledge of victory and an operative means to achieve it. Suggestively, Andrewes and Spenser were

contemporaries at both Merchant Taylor’s School and Pembroke College

Cambridge. The first part of FQ

(Books I-III) appeared in 1590, but direct influence on Andrewes seems

unlikely. Yet this and a significant

cluster of Andrewes’s other St Giles’s sermons offer a surprising number of

complementary texts for comparison with FQ Books I-III: on Michael’s battle with the

[146v] February the 4º 1598./ Vincenti

dabo edere ex arbore vitae quae est in medio./

A place of scripture purposely chosen that

wee might not departe from the consideration of those thinges wherein wee have

bene occupyed heretofore and yet suche as may fitly be applyed for our

instruction in the sacrament of the body and blood of Christ for though wee be

now in the

[¶] But the cheife poynt to be inquired is

how the holy ghost agreeth wth him selfe that man being debarred of

the tree of life is restored to yt, The

answere is Gen. 3.22. The

punishment laide uppon him was that he might not put fourth his hand and take

of the tree of life but if there be a power given to man to eate of the tree

Joh. 19. ii. then he maye

take of yt, man of himselfe may not rushe into

From the condition wee are taught that this

promise is not to be cast uppon us but geven and yt is not a generall promise but made particulerly

to him only that overcometh wch condicion carryeth us to the

promises of vertues made by god Gen. 3. where god proclaymeth warre

betwene the woeman and the serpent betwene the woemans seede and the serpentes

seede. And Christ tells us here that he

which is conquerour in this warr shall enioy

stirring in us fleshly lusts which fight

against the soule 1. Pet. 2. wch must be overcome as the

apostle

exhortes Coll. 3. mortifye your earthly

members but the harte also by that boyling Lust of Revenge wch made

Caine one of the serpentes seede to kill his brother 1. Joh. 3.12. wch inward desire of Revenge must

likewise be overcome as the apostle willeth

in yt is sowen in the harte of the Receavers

as yt were a kernell wch in tyme shootes fourth and becomes a tree

for as there was a death of the soule by sinne before god inflicted a death of

the body soe answerable to that first death of sinne there must be in us a life

of grace which is the roote of that tree from whence wee shall in due tyme

receave the life of glory[.] In this

sacrament the tree of the life of grace is sowen in us that is a measure of

grace wrought in our hartes by the power of godes spirit by wch wee

shall at length atteyne to eate of that tree wchshall conveye unto

us the life of glory. As there are two

trees of life, soe wee must have a double Paradise wee must haue a Libertye to

be of the paradise on earth that is the church military wch is

called hortus conclusus, Cant. 2. before wee can be receaved into

the heavenly Paradise that is the Church triumphant, Soe there is a playne

Analogye betwene those, As when wee are dead in sinnes and in the

uncircumsition of the flesh Coll. 2.13. wee receave the life of grace by

the sprinckling of the blood of Christ in baptisme soe when wee are fallen from

the life of grace and are restrayned from the life of god Ephe. 4. and

dead in trespasses and sinnes Ephe. 2. then wee obteyne victory against

sinne and death by the blood of the Lambe being druncke in the sacrament

List of variants

The Exeter manuscript reading appears first,

with reference by page and line to the transcription; there follows the variant

reading, located by page and line number of the printed text of 1657.

1.1 Vincenti]

Victori vitae] illa vitae medio.]

medio Paradisi Dei. 572.1

1.9 scriptures]

scripture 572.15

1.14 returne]

come 572.24

1.16 certyne

persons] the persons 572.26

1.17 whether

of theis] next, how these 573.1

that all] how 573.2 are]

or 573.2

1.19 And

these] and 573.5

2.18 1.

Cor. 10.2.] first epistle to the Corinthians the tenth chapter and the

third verse 573.35–36

2.30 John

17] omit 574.9

3.2 thinke

of] think 574.15

3.19 at

whose] whose 574.45

3.28 Ephe.

6.] cites also verse 12 575.10

4.8 blank

space] gain 575.33

4.13 scriptures]

Scripture 575.41 looke] look into 575.42–43 then] there 575.43

4.14 makes

us] makes 575.44

4.18 gott]

get 576.4

4.25 is

an] as an 576.13

4.30 abstinence]

abstinencie 576.21

5.3 Apoc.

12.11.] cites chapter only

576.28–29

5.5 second]

Secondly 576.33

5.11 a

sacrament . . . both] omit 576.42

5.14 harte]

hearts 576.46

5.21 military]

Militant 577.9

5.25 Ephe.

4.] cites also verse 18 577.17

5.27

5.28 suche

an] such 577.21

5.32 eate

of] eat 577.28

5.33 they

that] Whoso 577.29

6.1 for

ever, There] by me; And he that eateth of his body shall live for ever. 577.30–31

6.1 god]God first 577.31

6.3

6.13 et]

est 578.4

6.22 come

/ Amen.] come. 578.20

Notes. The annotations below document sources

(mostly biblical), translate Latin phrases, define difficult or now obsolete

words or senses of words, explain contemporary allusions, and cite passages

helpful for comparison either from elsewhere in Andrewes or other sources. Unless otherwise stated, all biblical

quotations are from the ‘

1.1 February

. . . 1598: Sunday, 4 February 1599. For Andrewes’s pattern of preaching at St

Giles’s, see headnote.

1.1 Vincenti

. . . 2.7.: closer to

Tremellius/Beza (‘victori dabo edere ex arbore illa vitæ quæ est in medio

paradisi Dei’, quoted exactly in AS) than Vulg. (‘vincenti dabo ei edere

de ligno vitæ quod est in paradiso Dei mei’).

1.2 thinges

. . . heretofore: Andrewes’s

on-going lecture series on Genesis; see headnote.

1.5-6 Gen.

3 . . . life’: Gen. 3.23-4, the

texts for Andrewes’s lectures on Sundays 21 and 28 January, 1599 (AS,

pp. 339-51).

1.8 first

state: prelapsarian state.

1.9 as

. . . told you: cf. the

peroration of Andrewes’s lecture (Gen. 3.24) preached the Sunday before (28

Jan.), ‘if we . . . shall be partakers of Christs Sacrifice, which worketh

reconciliation between God and man . . . then followeth the restoring of us to

the heavenly Paradise, And to him that overcommeth God will give to

eate of the Tree of life in the middest of the Paradise of God’ (AS,

p. 351).

1.10 acquisitio

novi iuris: Lat., ‘the acquisition

of a new law’.

1.10 in

this place: in this verse (Rev.

2.7); cf. lecture on Gen. 3.23, preached two Sundays’ earlier (21 Jan.), ‘the

second of the Revelations the seventh verse: So that that place sheweth a manifest return

to eat of the tree of life, and to take again the benefit of Paradise’ (AS,

p. 344).

1.11-12 Angell

. . . fiery sword: Gen. 3.24, the

text for Andrewes’s lecture 28 Jan. (AS, pp. 345-51).

1.15 Thone

. . . thother: i.e., ‘the one . . .

the other’ (as modernized in AS, p. 572).

1.17-18 Seraphins

. . . Joh. 12: Is. 6.2, Joh.

12.39-41.

1.19

Ezech. . . this Angell: A very

compressed reading of Ezekiel’s vision of the cherubim (Ez. 10), which suggests

that these supporters of the glory of God (the cherubim) adore the ‘Angel’ with

the two-edged sword and eyes of fire (Rev. 1.16, 2.18), that is, Christ.

2.1

2.2-3 Hebr.

. . . Cor. 2: Hebr. 1.14.; Acts

3.20-1, 26; 1 Cor. 2.8.

2.5 Gen.

3.22: the text for Andrewes’s lecture

on 14 Jan. 1599 (AS, pp. 335-9), which he treated as God’s

‘deliberation’ over executing the sentence of expulsion upon Adam and Eve.

2.7 Joh.

19.ii: i.e., John 19.11.

2.8 theife

Luke 23: Luke 23.43; an exemplum

used similarly in the lecture on 21 Jan. (AS, p. 344).

2.13 John.6: John 6.35.

2.17 Manna

2.18 1.

Cor. 10.2: an error for 1 Cor. 10.3

(as AS, p. 573).

2.19-20 2

partes . . . dabo: typically,

Andrewes divides the main parts of his argument according to grammatical units

in his text: ‘vincenti’ (‘to him

that overcommeth’), or overcomming sin, is the requirement or ‘condicion’ for

receiving (‘dabo’, ‘I give’) the ‘promise’ of eternal life.

2.20 coniunction: again, Andrewes makes grammar do theological

work; the conjunction ‘et’ (Lat., ‘and’) which links ‘vincenti’ and ‘dabo’

makes the necessary, and carefully balanced, theological point that eternal

life is a ‘guift’ not earned, but is also not given to those who are idle; the

‘et’ here carries an immense strain by trying to reconcile opposed

reformed and catholic views about the efficacy of human works in the economy of

salvation (see next note).

2.23-4 cooperari

. . . Joh. 6: Lat., ‘work together

for the food that does not perish’, a startling rephrasing of John 6.27

(‘Labour not for the meate which perisheth’; Vulg. and Trem/Beza, ‘Operamini

non cibum, qui perit’). The slight

adjustments of adding the prefix ‘co-’ to the main verb (‘operamini’), and

moving the negative modifier ‘non’ from it to ‘perit’, effects an assertion of

the cooperation of the believer necessary to obtain salvation that is foreign

to Elizabethan Calvinist soteriology, but found elsewhere in Andrewes (see

headnote).

2.28 Apostle

. . . Cor.12: Paul, 2 Cor. 12.1-4.

2.30 John

17: John 17.24 (the citation is

repeated, l. 31).

3.1-2 Mat.

. . . domini: Vulg., Matt. 25.21

(Trem/Beza, ‘engredere in . . .’); ‘enter into thy Master’s joy’.

3.3 wise

man Pro.13: Solomon; Prov. 13.12.

3.5 all

in all: a Pauline epithet; cf. 1

Cor. 12.6, 15.28; Eph. 1.23.

3.9 2.ii: i.e., 2.11.

3.13 Job.

14: Job 14.7.

3.16 center

. . . circumference: The garden of

Eden within ‘Paradise’ was traditionally thought to be a round hortus

conclusus, in the centre of which stood the Tree of Life (Gen. 2.8-9; cf.

3.17 coronam

vitae: Lat., ‘crown of life’.

3.17 1.

Peter 5: 1 Pet. 5.4.

3.20 Psal.

16: Psal. 16.11.

3.21 the

condition: the prepositional phrase

(‘to him that overcommeth’) which qualifies the main clause of the text (Rev.

2.7); cf. above, 2.19-20. Andrewes’s

interpretation of this ‘condition’ is a sustained qualification of strict predestinarianism:

eternal life is not forced upon (‘cast uppon’) any, but instead offered

(‘geven’) only to the believer who ‘overcometh’, or perseveres, in the struggle

against sin in the earthly life.

3.23 Gen.

3.: Gen. 3.14-16.

3.26 2.

Tim. 2.: 2 Tim. 2.5.

3.28 Ephe.

6.: Eph. 6.11-12.

3.29 2.

Cor. 12.: 2 Cor. 12.7.

3.31-2 warre

. . . inward partes: an orthodox

statement of the relationship between original and actual sin; cf. ‘Articles of

Religion’ (1571), no. IX: ‘Original sin

. . . is the fault and corruption of the Nature of every man, that naturally is

engendered of the offspring of Adam . . . so that the flesh lusteth always

contrary to the Spirit . . . . And this infection of nature doth remain, yea in

them that are regenerated’.

3.32 Reynes: lit., the kidneys; fig., in Biblical usage,

the seat of the emotions (OED ‘reins’, 1, 3).

3.33 1.

Pet. 2.: 1 Pet. 2.11.

4.1-2 Revenge

. . . Caine: anticipates Andrewes’s

extended treatment of the murder of Abel by Cain, and of Cain’s subsequent punishment

and progeny (Gen. 4) in the same lecture series at St Giles’s, preached during

term times from 7 February 1599 to 17 February 1600 (AS, pp.

363-499). Together, these lectures

constitute one of the most extended, and neglected, early modern considerations

of the immorality of revenge (discussed briefly in Tyacke, ‘Lancelot Andrewes’,

pp. 12-13). Their proximity to the

likely date of Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1600) is highly suggestive, and is

the subject of work in progress by the editor.

4.3 Rom.

12.:

4.3-4 sed

. . . bono:

4.5 mortification: ‘the subjection or bringing under control of

one's appetites and passions by the practice of austere living’ (OED

I.1).

4.5 wthout

us: outside of us; external

temptations to sin (as opposed to the prompts to sin ‘within us’ from original

sin and lusts of the affections; cf. above, 3.32).

4.5 filij

Beliall: Lat., ‘children (or sons)

of Belial’; common Old Testament epithet for evil people, by New Testament

times understood in the Judeo-Christian tradition as servants of the devil; cf.

Judges 20.13 (Bishops’ and Vulg.); Geneva consistently translates as ‘evil men’

(cf. Judges 19.22), with the Hebrew transliteration used only in marginal

notes.

4.6 John

8: John 8.44.

4.10 The

Apostle: Peter

4.15 continere

a peccato: Lat., ‘to hold back from

sin’

4.16 penitere

de peccato: Lat., ‘to repent of sin’

4.18-19 gott

. . . head: ‘to gain force, ascendency,

or power’ (OED, ‘head’ 52; citing 1625 as the first usage of the phrase

‘to get head’).

4.23 Isa.

28.: Is. 28.18.

4.25 Pro.

7.: Prov. 7.22.

4.26 Ezech.

14: Ezek. 14.3.

4.28 drawe

nere: physically approach, quoting

the minister’s invitation to recite the General Confession before receiving the

Holy Communion (BCP): ‘You that do truly

and earnestly repent you of your sins . . . Draw near, and take this holy

Sacrament to your comfort ; make your humble confession to Almighty God . . .’.

4.29-30 snatch

. . . repentance: an orthodox

English protestant insistence that the worthy state of the believer’s soul is a

condition for the efficacy of the Holy Communion; cf. Articles of Religion

(1571), no. XXV: ‘And in such only as

worthily receive the same, they have a wholesome effect or operation’.

4.31 de

furto . . . jure: Lat.,

‘deceitfully, but not lawfully’.

5.1-2 bread

. . . gravell: correlative to

4.29-30, unworthy receiving of the Holy Commonion is damnable; Article

XXV: ‘but they that receive them [the

sacraments] unworthily, purchase to themselves damnation’.

5.2 Pro.

20.: Prov. 20.17.

5.7 vincenti

. . . edere: Lat., ‘to him that

overcommeth to partake and to him that partaketh to overcome, I will cause

(give) him to eat [of the tree of life]’; Andrewes’s own cleverly chiasmic

combination of the main text (Rev. 2.7) and 1 Cor. 10.16-17, epitomizes the

‘reciprocation’ whereby, in the worthy receiving of the holy communion, the

believer is simultaneously rewarded for overcomming sin and given strength to

overcome sin; cf. 5.9-10.

5.11 wee

have . . . wee have: the repetition

is caused by the copyist’s ‘eyeskip’ error (moving back to the wrong point in

the copy after the eye has wandered; frequently found when starting a fresh

page, as here).

5.11 means

. . . pledge: for the holy communion

as both a confirmation (‘pledge’) and an operative strengthening of faith, see

Article XXV: ‘[sacraments are] not only

badges or tokens of Christian men’s profession . . . and doth not only quicken,

but also strengthen and confirm our Faith in him.’

5.13 Roote

. . . Christ speakes of: although

the allusion is highly compressed, probably the parable of the tree and the

fruit from the Sermon on the Mount: ‘So

euery good tree bringeth foorth good fruite, & a corrupt tree bringeth

forth euill fruite.’ (Matt. 7.17).

5.20 two

trees of life: the historical Tree

of Life in Eden (Gen. 3.23-4, and the future Tree of Life in heaven (Rev. 2.7).

5.20-1 Libertye

. . . on earth: the freedom, or free

will, to participate in the life of the church; perhaps another counterpoint to

a strict Calvinist definition of the true church as the predestined elect.

5. 21 church

military: church militant, the

church on earth (vs the ‘church triumphant’ in heaven, 5.22).

5.21 hortus

. . . Cant.2.: incorrect citation

for Canticles 4.12, ‘My sister my spouse is as a garden inclosed, as a spring

shut vp, and a fountaine sealed vp.’ (Vulg., ‘hortus conclusus soror mea sponsa

hortus conclusus fons signatus’). The

allegorization of the enclosed garden as the church was first made by Gregory

the Great: ‘horta sancta ecclesia

existit’ (‘the garden is deemed to be the holy church’) (Expositio Super

Cantica Canticorum, IV.17), and became a commonplace. Cf., among the prayers for the ‘continuance of the true institution of the

Sacraments’ in Thomas Bentley, The Monument of

Matrones (1582): ‘I AM come (saith Christ vnto his spouse the Church) into my garden, my

sister, my spouse: I gathered my mirrh with my spice, I ate my honie-combe with

my honie: I dranke my wine with my milke. Eate ô freends, drinke, and make ye

merrie ô welbeloued.’ (p. 568).

5.25 Ephe.4.: Eph. 4.18.

5.26 Ephe.2.: Eph. 2.1.

5.27 Apo.12.: Rev. 12.11.

5.28-30 power

. . . sacrament: cf., from the

sermon preached at St Giles’s 1 October 1598 (on Is. 6.6), ‘in the Sacrament he

doth so elevate a piece of bread, and a little wine, and make them of such

power; that they are able to take away our sinnes . . . he can so elevate the

meanest of his creatures; not only the hemme of a garment, but even a strawe,

(if hee see it good) shall be powerfull enough, to save us from our sinnes’ (Selected

Sermons, ed. McCullough, p. 143).

6.1 Deut.

30.: Deut. 30.20.

6.1 ipse

. . . mea: cf. Vulg., Deut. 30.20,

‘ipse est enim vita tua’ (‘for he is thy life’); the change here and in AS

to the first person predicate (‘ipse enim est vita mea’; ‘for he is my life’)

may be authorial, but is probably a note-taker’s or copyist’s error.

6.3

6.4 Joh.

5.: Joh. 5.26.

6.6 Cesterne: cistern

6.6-7 wisdome

. . . Christ: Wisdom, personified as

female in the Old Testament, was interpreted by Christians as a defining

attribute of the second person of the Trinity (Christ), through whom divine

knowledge is conveyed to mankind; cf. from Andrewes’s funeral sermon by John

Buckeridge, ‘for Christ is made to us wisdom from God’

(appended to Andrewes, XCVI Sermons, p. ‘51’ [15]).

6.7 Christ

. . . 3.18: Of Wisdom it is said

that ‘She is a tree of life to them that lay holde on her, and blessed is he

that retaineth her.’ (Prov. 3.18). Using

the traditional identification of Wisdom with Christ (see prev. n.), Andrewes

cements his analogy between eating Christ’s body in the eucharist and eating

the Tree of Life in heaven. The

6.7 in

ipso . . . 14.: i.e., Joh. 1.4: ‘in ipso vita erat’ (Vulg.), ‘in it [the

Word, Christ] was life’ (

6.8 Joh.

14.: Joh. 14.6 (‘Iesus sayd vnto

him, I am that Way, and that Trueth, and that Life. No man commeth vnto the

Father, but by me.’).

6.9 blood

in Baptisme: traditional baptismal

doctrine, applying the soteriological reasoning that the grace to wash away sin

could only be bought by the blood-sacrifice of Christ; cf. Andrewes, Whitsunday

1615: ‘And the

baptisme of the

bodie, is but the bodie of baptisme; the soule of baptisme,

is the baptisme of the soule.

Of the soule, with the blood of CHRIST, by the hand of the Holy

Ghost’ (XCVI Sermons, p. 679).

6.9 actuall

sinnes: sins committed after baptism

(i.e., vs original sin). Cf.

sermon at St. Giles’s, 1 October 1598, ‘By one bodily sacrament [baptism] he

taketh away the affection unto sin . . . .

By another bodily Sacrament [eucharist] he taketh away the habituall

sins, and the actuall transgression, which proceed from the corruption of our

nature’ (Selected Sermons, ed. McCullough, p. 143).

6.13 fructus

. . . 11.30: Prov. 11.30 (Vulg.);

‘The fruite of the righteous is as a tree of life’.

Selection 2. 1. Gen. 11. v. and it was soe. 12. v. and the

earthe brought fourthe the budd of the hearbe etc. 13 v. soe the evening &

the morninge were the third day./

What follow are notes, transformed through extensive revision in the

1657 edition, pp. 72–111. Immediately

preceding these notes is a more finished draft of what essentially appears in

1657, pp. 65–72, that is, the full section on Gen. 1.11 (ff. 33v–37r). Thus there are in fact two versions in the

manuscript of this section, both evidently copied at the same time but one from

an earlier and the other from a later version.

The earlier, unrevised or first version is given here.

[37r]

Wee have heard of godes decree commaunding; & the returne executing

it & his censure approving that is made, wch in every dayes worke is sett downe in

theis three phrases, fiat, erat sic, & bonum erat. of this third dayes worke wee have handled

before wee have heard the first parte namely godes worde commaunding ye earth

to budd fourth leaves & seeds & trees etc nowe it remayneth to speake

of theother two: & first of ye returne and execution and it was

soe. for the earthe according to every

iott & title of godes worde fullfilled godes will & brought fourth all

sortes of hearbes, & trees, & buddes, & fruites, & seedes,

leaving no thing undone wch was commaunded./

Touching wch, besides the obedyence of this Element in

executing godes decree wee note a speciall certificate under godes hand as it

were for the discharge of this creature, in ye dispatche of his

worke & that without delay with all haste & speed wch reproveth

not onely our disobedience to god, but also our dullnes & slownes in doeing

any thing wch god commaundes.

for wth us it is one thing to doe a thing & another to

doe it willingly & quickly with expedition & speed. for when god doth commaunde any thing, wee

put it of[f] wth this delay erit sic, it shalbe soe hereafter

when wee can finde leasure & fitt tyme:

it can seldome be saide in the present tense erat sic, it was

performed without delay. for wee are as

Salomons debtors, wch bidde god stay till to morrowe or the next

day. 3. prov. before he can finde leasure to pay this debt & duety

of obedience. Secondly in that the

retourne in the end of the ii. v. was erat sic, it was soe two thinges

are to be noated out of the nature of the worde first is a congruitie of the

performance answerable to the commaundement in every poynte; for here is

specifyed iust so much done as was required, nothing to much or to litle. to teache us yt our obedyence must

be suche, we must not deficere in necessarijs nec abundare in

superfluijs. The other poynte is for

contynuance or perpetuitie, for ye word signifyeth yt it was soe

surely & firmely done as if it had a sure basis or foundation for

continuance. yt it might

never fayle, wee see it holdeth & endureth id hunc usque diem, our

eyes and experyence seeing yt it is soe.

The last thing wee gather by opposition, yt godes worde was

the cause & is, yt hearbes & trees do beare *fruites &

seedes. soe & contra, it is the [37v]

same word of god saying let not the earth nor the trees beare wch is

the cause of unfruitefullnes & wante if for our sinne they fayle any yeare ab

eius edicto fertilitas, et ab eius interdicto sterilitas: if therefore wee disobey godes worde, this

wilbe our punishment, yt his worde shall forbid ye earth

to yeild encrease & to deny us his fruites./

The Second parte is the censure & approbation of god sayeng that it

was good. I sayed before there are 3

sortes of goodes .1. honestum .2. utile .3. iucundum. each of wch wee shall see in the earthe & the

fruites thereof for honesty & morrall good wee see it is gratefull to the

owner or sower wch laboureth therein, faithfully & gratefully

repaying & requiting his cost & labour thereon. for perfitt it yealdeth pabulum et

latibulum both for man & beast. & soe necessarily good is it in

this respect yt without it the king cannot lyve. 5 Eccl: 9.

for pleasure and delight either of the eye to behold it or of the taste to

relieve it, it is most delicious & delightfull. mylk [space] wyne &

oyle wheate & all other grayne wch are both for varietye and

necessitye, wee receive by godes blessing from the fruite and encrease of the

earthe & trees. & therefore is every way good./

[37v]

1 Gen: 14. and god

saide let there be lights etc./

In this fowerth dayes worke is set downe the creation of lightes &

the adorninge ye heavens wth light & starres for us

before god made the earthe a garden full of trees hearbes & flowers so now

he intendeth to make heaven beautifully replenished with starres & planetts

of light/

Here then wee shall see the first rising & shining of ye Sonne

ye first coniunction of the new moone, & god now first calling ye

starres out by theire names & making them appeare 14v Psal: 4 nowe

the Sonne being first marryed to the light, he cometh this day like a glorious

bridegroome out of his chamber to runne his course. 19. Psal: 4. &

all the starres as freindes of the bride wth ioy accompaning them.

3v Job. 7./

Nowe to the wordes themselves In dixit deus etc is conteyned the

decree in wch three thinges are to be noated i the thinges to be made & created. 2.

the situation or place of them 3 the use & end, wch is to divide

light from darkenes & to be for signes etc

For the first one would thincke this commaundement to be needles because

theire was light created before: but this was most necessarily ioyned to the

former, yt whereas onely light was made before now theire might be

vesselles to conteyne and carry, for before the light [blank space] was

dispersed and diffusedly spreading it selfe abroad, but nowe, but nowe it is

made as it were a piller of light, beeing brought into the greate bodyes of

planettes & starres & into certayne glorious vesselles to conteyne it

& conveye it to all soe that the estate of the light made before is

bettered, sublimed & made more excellent then it was before./

[38r] The second is the place

& situation of theis starres and lightes wch is heaven the most

fitt & convenient place that might be for three respectes: first godes

wisdome knewe it meetest in regard of the cause, that wee may know from whome

cometh this grace nam sursum a patre luminum 1. Jac. 17:

Secondly in respect of the Convenyence of ye place, for in a

house the best place to sett ye Candle or light uppon is uppon the

topp of ye table. 5. Mat. or uppon some highe place that it

may the better give light to every place therein. Thirdly it is a place of safty for the great

& precious a benefitt for yt place being soe highe & out of

all mens reaches, neither vis nec fraus, neither the force & power

of strong men, nor the Craft of subtle malicious men can take it from the world

& bereave it of this benefitt. for

it is ye nature of rich covetuous & malicious men to [blank

space]. all good thinges especially ye

best to theire owne private use & gayne, though they bereave others

of the publicke & common benefitt wch is theires by right. Therefore god hath soe placed theis lightes,

yt as all wch have eyes may see thereby soe none have

suche handes or armes to take them away./

Nowe touching the endes & uses for wch god made them, the

first is to divide light from darknes, wch is necessary because

elles there would be a confusion, & soe the beautie of the starres for want

of ordering & disposinge ye cloudes grosse darknes would not

appeare. They serve for divisions &

distinctions many wayes betwene night, & day, sommer, & wynter, hott

& could, dry & wett seasons./

Secondly they are for signes.

for god hath geven them a power & influence as it may seeme, to

signifie & shew divers thinges to men yet this doth not make muche for

[blank space] & Judiciall Astrologers, but rather against them. for if there be onely coniecturall signes

then wee may not build a futall necessitye uppon them. for being onely figures to forwarne us of

thinges, then it is in us to avoyde them if they be evill, & procure them

if they be good. Therefore god sayeth .20

Jer: 2. be not affraid of the signes of heaven. god hath not sett them to take away the feare

wch [blank space] to him,

& to give it to them./

God hath sett them for signes naturall to tell us when it is tyme &

season to sowe fytches, barley & wheate. 28. Esay. 25.26. they be

husbandmens signes to know when to plant, to pruine & cut theire trees,

& when to gather fruites. for

marriners & seamen they be signes & markes to knowe when & howe to

divert theire course. 27 act. 4.

& they are signes for Phisitions & Surgions in theire severall

artes. yea they are signes to warne both

man & beast that the night is at hand by the evening starr, & yt the

day doth approach by the day starr & therefore when it is tyme both to

sleepe & arise. 104. Psal. [38v] Yea there are Commettes

& great blasinge starres 65. Esay 8. wch are signes &

tokens of godes wrath for sinn to summon us to repentance & to amend. And thus diversly they are signes to us./

The last is the most [blank space] & yt is to be lightes

geving light to all. It had bene no

benefitt to us if onely they had bene endued wth light for themselves

& had not communicated any parte thereof to us but had left us still in

darknes. Therefore god created them not

for themselves but for us, & our use & benefitt. God yt as ye heaven

& heavenly starres are for ye earth, soe ye heaven

& earthe & all is for the use of men.

Wherefore wee see yt god hath not made man for ye Sonne

or moone etc. to serve them, but they for ye service of man wch sheweth the base & grosse Idolatrye

of ye gentilles wch omitting the worshipp of god yt made & gave them did serve & honour ye

Sonne & moone & starres yt is suche creatures wch

god made ministers & servantes to us god havinge exalted us in

dignitye above them 8 Psal:./

There are Fower endes of all thinges wch god created all wch wee may observe in the light. first they are assigned to theire severall

functions for as the eye is made to see & the eare to heare, soe are the

starres to shine & give light, & therefore Sol est oculus mundi

without wch all is blinde.

Secondly god made alwayes ye inferiour Creature to serve the

superiour, soe all thinges in earth & heaven are created for the benefitt

& service of man. Thirdly he hath

made all theis innumerable Creatures for the beautifieng adorning &

replenishing of the whole world wch is his glorious worke & howse

for man to dwell in; so as hearbes & plantes & trees did beautifie the

earth belowe, the starres & lightes did adorne the heavens the upper parte

thereof. Lastly god made the heavens

& earth & men & all thinges elles propter se for his owne

service, honour & glory. 38 Job: 7. wch is the mayne & generall end of all

the Creatures that are.

i. Gen: 16.17.18.19. v.

god then made two great Lights &c

& god set them in

the firmament of heaven to shine &c

& to rule in the

day & night & to separate the Light &c

& god sawe it was

good &c./

Wee have shewed before the decree or iniunction of god; nowe of the

execution & accomplishing thereof: & of godes censure & approbation

of it. the first whereof is to ye end

of the 18 v. the other is the very end & conclusion of the 18 v. & god

sawe it was good.

Before in the former workes the returne was fuit sic, it was even

soe as god commaunded: but in this worke, here is a more large declaration of

the doeing & fullfilling godes decree specifyeng the efficient who made the

starres even the same god and the same word wch did commaunde it

agreeing wth yt wch John i

John. 23. by the word were all thinges created & without it was nothing

made yt was created. Beeing then the Sonne & moone are but

the creatures of god they are not to be adored & worshipped as the

god ye creator of them. 33. psal 6./ [39r] By

the word of his mouthe were the heavenes made, & all the hoste of them by

his spirit or breathe. soe that there

was nothing elles yt had a finger in this worke but onely the

almightie god & glorious Trinitye, & therefore all the glory and prayse

of this worke must wholly be given to him wch causeth the prophet

David to invite the Sonne & moone & all the starres to prayse &

magnifye the Lord, as theire onely creator. Ps: 14. v.5./

If any aske of what matter god made theis fayre and glorious bodyes of

the sonne & moone & Starres, the answere is conteyned in the nature of

the word. For the heavens being made of

the waters & by the waters by the power of god, the heavens do bring theis

heavenly bodyes of the same matter & nature whereof they were made, as the

earth doth bring fourth plantes & hearbes and trees, of the same matter and

nature of wch it selfe was 37 Job. 18. god did spread the

heavens as glasse etc [blank space] For ye manner & order wch god observed

in making them, wee see yt god first made the Two greater lightes

the Sonne & moone & then the infinite nomber of Starres./

But this is offensive to some curious Astronomers, wch by

mathematicall instruments fynd that the moone is lesse then divers planettes

& starres; but theis Cavillers doe not vaynely carpe & like a dog barke

at the moone. For Moyses calleth the

Sunne & Moone greater, not in regard of the quantity or greatnes wch

they have but in respect of us, to whose appearance they seeme farr greater

then all the rest. yea because it is

manyfest yt they geve more & farr greater light then all the

rest besides. wherefore wee see this

word great is geven not soe much to the quantitye of greatnes in substance but

to the qualitye & dignitye of thinges wch in greater degree of

excellencie are above the rest. as

Moyses is said to be a great man. ii. Exo. 3. wch in respect

of the quantitye of his body as in regard of his excellencye & dignitye

above all the rest. In wch sense

it is saide that ye disciples did strive who should be greatest

& yt is not for bignes of body, as for the greatnes of dignitye

& estimation wch they soe muche desired; as many litle men now

do soe seeke to be greatest. But

But touching the bodyes of theis starres it was necessary yt all

of them should be great, because the howse to wch they should give

light was very great. And it was

needfull to make the greater lightes in nomber to be two because the Two tymes

of night & day & the two great bodyes of the earthe & the sea are

ruled by them. And it was meete and

convenyent that theis two should be in pares, one greater then other & not

alike; because ye world hath most need of the best and greatest

light in the day for direction of our worke./

And therefore god made the moone of a dymmer & lesser light [39v]

because they yt sleep sleeping in the night, may as well and better take

rest with the least light. yet god

would not now have the night as before utter darknes without all light but

caused the moone to be quasi nocturnus Sol. yt ye watchmen on land,

& Shipmen by sea might have some direction both to watche & sayle./

And thus much for the two greater lightes, now for ye starres.

Theis lesser starres are made by god, sometymes to be forerunners of the

sonne & moone, sometymes to attend & waight as it were on them; &

sometymes in theire absence as theire deputies to shine & serve alone. Soe yt they not onely beautifye

the heavens, but also they are made to be a benefitt to us. Some of theis starres are fixed &

immoveable; other are planettes movable & wandering in theire Spheres, wch

are in nomber seaven expressed in godes worde./

And thus much for fecit, yt god made them all great

& litle.

Nowe wee heare in the 17 v. that god wch made them did also

sett & seate them in the firmament of heaven. The reason of theire severall places wee know

not, but god hath ordered them in great wisdome & in a most comely order as

they stand. 1 [?] 5./

The use & end why god placed them there, is not onely to give light

to us, but also to distinguish betwene the night & day & to manage

& rule them both by ye direction of light. by meanes of them wee see hurtefull thinges

to avoyd them; wee distinguish betwene thinges difference & doubtfull to

discerne them & then wee are able [blank space] thinges wch

are good to make choyce of the best by theis lightes & starres thus

placed. god giveth a Comfortable

influence from heaven to the earthe & earthlie thinges belowe: for all the

vertuous operations of the heavens doe by godes ordinance geve attendance to

theis lightes & by them are conveyed to thinges on earth yet the Starres

doe beare no sway nor rule neither have any power in the mindes of men, for god

reserveth the rule of them to himselfe, ordering, disposing & tourning them

as the rivers of water pro v./

The last use & end of the starres are to divide soe the light of the

day maketh the wild beastes afrayd & divideth or driveth them into deserts

& desolate places into theire dennes & holes of the earthe wth theire shining [i.e shunning] the light is a

safegard & safty to mankinde. 104 Psal: 24. The absence of the Sonne can causeth the night

dividing it from the light of the day yt being dedicated to rest

& sleepp as this is to labour & worke./

Nowe for godes censure & approbation saying yt they are

good. The goodnes & benefitt of wch

is most evident to all. First for

the goodnes of delight & pleasure Salomon sayeth. ii Eccle: 17 v. profecto

lumen bonum et iucundum est. soe

ioy full & comfortable it is that Toby wanting the benefitt of it sayeth

what ioy or pleasure can I take seeing I cannot beholde the light of the Sonne

and therefore some thinck that Sol hath his name a solatio, of solace

and delight, because all thinges doe take suche pleasure therein./ And it is

absolutely necessary & good, because without it our iudgementes could not

be able to discerne or iudge of Collars./ [40r] It is good also for

direction of our wayes howe to walke & for our workes to knowe howe &

what wee should doe 11 John walke while ye have the light, for when the

night cometh men know not whether they goe.

This then is an argument of godes great goodnes & mercie to all, in

that he suffereth & hath sett the Sonne & theis lightes to shine &

give light to all, as well to the wicked as to them wch are godly

& good. 6 Math:

i. Gen. 20.v. Afterwarde god

saide Let the waters bring fourth in abundance every creeping thing that hath

lyfe & let the fowle fly uppon the earth, in the open firmament etc

This verse & the three following doe conteyne in them the fyft dayes

worke, by wch both the waters are stoared with fishe & the ayer

and firmament was replenished with fowle.

for yet hitherto they were like to wide & great stoarehowses wch

were empty & voide In wch

dayes worke are fower branches 1

the edict or precept. 2 the execution or performance of it. 3. the allowance

& commendation of it in the end of the 21 v. lastly another speciall

precept, for the preserving of theis thinges soe made in the 22 v./

Touching the commaundment wee may note that to saie or to commaunde in

word may seeme to be but a weake thing.

For wordes we holde to be but wynde yet suche wordes as god speaketh doe

receive suche & soe great power & authoritie from the speaker or

commaunder yt of necessitye that wch is saide must needes

be done./

If a king do commaunde, the power of his authoritye being ioyned wth

ye weakenes of his word doth cause it to be very powerfull

& effectuall. If princes authoritie

can make his word soe great, howe much more can godes omnipotencie geve

strength to his worde & cause that wch he sayeth be most

certaynely done. This thereupon yt by

vertue & force onely of his word whatsoever he sayeth is done and cometh to

passe./

The second thing to be noted is to whome god spoke, namely to the

waters. for as Moyses was willed to

speake to the stony rocke 20. Numb. 8. soe doth god here speake to the

waters. neither is it a fond thing thus for god to speake to deafe &

senseles creatures. for though they have

no eares & cannot heare, yet they can understand when god doth call &

speake to them, & have power to doe his will when he commaundeth. if then the waters and rockes can heare &

understand & doe what god doth saye & bid them, howe much more should

wee wch have eares and understanding hartes & active handes take

heed wee doe the like./

Nowe touching the Tenor of godes precept, wee see it concerneth the