- In the poem "A General Prologue to all my Playes" which prefaces

the works in her 1662 collection of drama, Margaret Cavendish writes:

But my poor Playes, like to a common rout,

Gathers in throngs, and heedlessly runs out,

Like witless Fools, or like to Girls and Boyes,

Goe out to shew new Clothes, or such like toyes:

This shews my Playes have not such store of wit,

Nor subtil plots, they were so quickly writ,

So quickly writ, that I did almost cry

For want of work, my time for to employ:

Sometime for want of work, I'm forc'd to play,

And idely to cast my time away…. (sig. A7)

Her modest disclaimer here is both typical of her own public assessment

of her work and remained a common thread among scholars examining her

writing until relatively recently. For the past fifteen years, however,

this dim view of Cavendish's literary output has been challenged by a

growing number of scholars, in part through the hosting of regular bi-annual

conferences and the eventual establishment of the Margaret Cavendish Society.

Since the first Cavendish conference in 1993, Gweno Williams of York St

John College has upheld the belief that the Duchess of Newcastle's nineteen

plays were not written exclusively for silent 'closet' perusal, but remain

fundamentally performable texts in their own right. To support and explore

this contention, Williams established the Margaret Cavendish Performance

Project in 1999, in which theatre students collaborate through workshops

and rehearsals to stage these plays and introduce them to modern audiences.

On July 19, the attendees of the 2003 Margaret Cavendish Society Conference

at Chester College were treated to two contrasting performances of Cavendish's

drama: a selection of scenes from the plays enacted live by six members

of the Performance Project, followed by a film screening of a full production

of The Convent of Pleasure (1668) produced and directed by Williams

in June of this year. These excellent productions demonstrated clearly

and convincingly that the Duchess did indeed write for performance, for

the delight of performers and audience members alike.

-

Staged with a minimum of sets and props, and enhanced by both costumes

and music from the 1920s, the scenes selected by the Performance Project

members were organized loosely around the themes of the MCS conference

along with Cavendish's expressed purposes in writing plays. The four actors

played multiple characters and, in conjunction with their director George

Brichieri and stage manager Helen Atkinson, worked closely together to

make clear and inventive decisions about how to bring these texts to life.

Opening with an adaptation of the 1662 "General Prologue" as

a monologue, Catherine Sercombe portrayed Margaret Cavendish herself,

bringing out the author's appeal to her audience through both self-deprecation

and evident pride in her own inventiveness. Sercombe's delivery of the

Duchess' concluding wish that "[her] works in Fame's house might

have room" evinced a charming self-confidence. As a sequel, Kate

Horlor delivered the Prologue to Love's Adventures (1662) with

a sly wink at the audience at the notion that a "want of understanding

Braines," rather than any flaw in the writing itself, might be at

the root of a play's bad initial reception. The message was clear: what

we were about to see would be fun and engaging, and thoroughly unapologetic

for itself.

-

The following pair of scenes from Lady Contemplation (1662) made

good on this promise. As Lady Conversation and Sir Experienced Traveller,

Liz Warren and James Browne relished the witty exchanges of their characters-their

light emphases on puns such as "breed" and "barren"

informed the flirtation between them, while Browne's description of a

national character as "tempered with moisture" gained added

appeal with his offering of a cocktail at precisely the right moment.

Browne and Warren clearly delighted in both the rhythms and eroticism

of Cavendish's prose, in which English becomes "the butter made from

the cream of other languages." The later excerpt from the play found

Warren's Lady Conversation outraged over having been slandered, fuming

to Sercombe's Grave Matron, "why may not a woman revenge her scandalized

honour as well as men?" The Duchess' exploration of gender inequalities

came well to the fore here, as Warren strongly made her case for revenge

only to be rebuked by Sercombe's pointed observation that vengeance would

inevitably lead to further disgrace. Neither the author nor the actors

shied away from the political implications of the importance and limitations

of a woman's reputation.

-

Youth's Glory and Death's Banquet (1662) provided the material

for the subsequent scene, inventively appropriated as a dialogue between

the actors 'backstage' as they prepared for the performances to come.

By delivering the play's thoughts on acting as they dressed for the next

scene, the actors highlighted Cavendish's metatheatricality and enjoyed

the opportunities presented for thespian bandying. Their choice of material

was admirably suited as a preface to selections from The Convent of

Pleasure (1668), since that play is perhaps Cavendish's most overtly

theatrical text in its tale of a prince disguising himself as a princess

in order to infiltrate the all-female society established by Lady Happy.

As the Princess, Browne initially entered in a dress and fur stole to

find Horlor's Lady Happy (in a delightfully appropriate touch) reading

A Room of One's Own. Eschewing the undoubted temptation to indulge

in high camp as he made his case to be admitted to her society as her

(platonically) romantic 'servant,' Browne's subtle portrayal allowed the

audience to see both the comedy and the romance in the burgeoning relationship

between Lady Happy and her new guest. Their final couplet about the "innocence"

of their liaison thus took on a particular charge, as Browne spoke his

half of the lines ("Nor never Convent did such pleasures give,/ Where

Lovers with their Mistresses may live") with a raised eyebrow at

the audience. Later, Horlor delivered Lady Happy's monologue about the

possibility of falling in love with a woman with creditable confusion

and frustration at not being able to "love a Woman with the same

affection [she] could a man;" Browne's re-entry in masculine attire

to persuade her of the "harmlessness" of their love enabled

the actors to emphasize the sexual complications at the heart of Cavendish's

play and to hint at its ultimate heterosexual resolution.

-

The final selection took up the Epilogue from Youth's Glory and Death's

Banquet, in which the actors simultaneously voiced Cavendish's submission

to her audience's judgment and invited this audience to participate in

a talkback session with the Performance Project members. Not only was

the subsequent question-and-answer session rich and informative regarding

issues such as the choice of scenes and setting, the particular challenges

of working with Cavendish's language, and the varied demands that her

plays present to performers, but the Project members also revealed that

they had put together the evening's work through only two weeks of rehearsal,

having never all worked together before! Their contagious interest and

delight in working on these plays, as evinced by Williams' proud observation

that her students "keep coming back" for more opportunities

to do so, was admirable proof of the performative potential and appeal

of the Duchess' plays to actors.

-

After a brief interval, Williams introduced the filmed full-length production

of The Convent of Pleasure that the second-year students of her

Renaissance Theatre Module had made on June 3 and 4 of 2003. Noting that

the production cut only one song from the text, Williams remarked that

the show as filmed by George Brichieri was merely 65 minutes long and

thus neatly annulled the common charge (one which the Duchess herself

feared) that Cavendish's plays are too long to produce in their entirety.

The film was derived from two live performances; thus, although devoid

of the kinds of special effects that modern moviegoers have come to expect,

it emphasized the energy of the student performers and the simplicity

of the staging. The action took place on a bare set, upon which the members

of the acting company themselves became the décor as necessary-instead

of exiting, for instance, the ladies of the Convent lay on each side of

the playing space, appearing almost like a group of pillows in their costumes

and immobility. These setting choices were deliberate, echoing as much

as possible the resources of the kind of seventeenth-century country house

in which Cavendish's plays might originally have been performed.

-

Intriguingly, the cast of this production was all-female, with the exception

of one male student who adamantly refused to play the Princess; consequently,

Williams explained, the students had to re-think their initial casting

of the play and adapt their work to the actors at hand. The resulting

performance thus relied greatly upon effective costume choices (male characters

in doublets and hose, female characters in long hoop skirts) to make the

gender designations clear to the audience. Masks were also crucially and

inventively employed: all of the 'gentlemen' wore black half-masks, while

the Princess (Kirstin Mack) wore an elaborate feathered half-mask in her

female guise, switching to a plain brown half-mask when her male identity

was finally revealed, thereby remaining in line with the masculine attire

of the other characters while highlighting the multiple performance levels

inherent in the Princess's role. Only Lady Happy (Sarah Fennell) never

wore a mask, thereby emphasizing her ingenuous nature. These casting and

costume choices were notably potent as a contrast with the choices made

by the Performance Project in their live production of selections from

this text: seeing the Princess performed by a female actor clarified the

ease with which the Convent members were duped into believing that disguise,

and brought out Lady Happy's confusion and dismay at falling in love with

someone she believes to be a woman.

-

One particularly striking feature of the filmed production was the extensive

use of choreographed movement and dance, specifically to make some of

the long speeches of the Princess and Lady Happy physical. As Lady Happy

set out her organization of the Convent of Pleasure, her ladies enacted

her ideas as she spoke; when the Princess played the role of Neptune in

a masque at the Convent, the ensemble's stylized movements became those

of the waves and the denizens of the sea. These moments not only enabled

the whole company to work together as an ensemble, but underscored the

lyrical descriptions within the play's speeches. In a programme note,

Williams pointed out that the use of movement and dance "sprang from

students' strong desire to articulate and reformulate their research into

C17 theatre forms such as masque and pastoral." Pedagogically, then,

the performance clearly enabled the students to apply what might otherwise

have been purely theoretical work: an excellent example of practical research

in action.

-

The Convent of Pleasure's rapid scenes and numerous instances

of play-acting provided ample opportunities for each member of the company

to create individualized characters within the play's framework. Fennell's

idealistic Lady Happy, enchanted with her own creation, was suitably taken

aback and genuinely tormented by falling in love with the Princess, while

Mack's Princess was gracious and formal in female guise and surprisingly

forceful and demanding (as the text requires) once 'his' cover was blown.

As Madame Mediator, Victoria Smith had several scene-stealing moments,

particularly in her emphatic deployment of her fan and her willingness

near the end of the play to "sacrifice [her] body" to the invading

male army in order to protect the Convent's virginal inhabitants. The

'gentlemen' were (appropriately) anything but, appearing instead as seventeenth-century

beer-drinking pleasure-seekers, while the ladies of the Convent created

funny and poignant vignettes in their portrayal of the play-within-a-play

detailing the manifold ills that marriage presents to women. By the end

of the film, a final star turn belonged to Jenny Payne who, as the jester

Mimick, brilliantly delivered the play's closing lines (debating hotly

with her own motley mask as to how best to prepare an epilogue to order)

and epilogue with consummate panache.

-

It is a truism that one realizes a great deal more about a play upon

seeing it performed than one can ever understand by reading the text alone.

Yet the members of the Margaret Cavendish Performance Project and the

Renaissance Theatre Module of York St. John College made this observation

fresh and new through their innovative productions of the Duchess of Newcastle's

plays. They brought out the energy, the liveliness, the bawdiness and

comedy, and the sheer exuberance of Cavendish's writing, showing just

how much her work can appeal to an audience even as it addresses topical

issues such as gender inequality, same-sex love, and the importance of

reputation. In the prefatory material to her 1668 collection of plays,

Cavendish wrote:

Having observ'd, that the most Worthy and most Meritorious Persons

have the most envious Detractors, it would be a presumptuous opinion

in me to imagine my self in danger to have any: but however, their malice

cannot hinder me from Writing, wherein consists my chiefest delight

and greatest pastime; nor from printing what I write, since I regard

not so much the present as future Ages, for which I intend all my Books.

(sig. [A2])

Judging by the loud and well-deserved ovations given to the performances

on July 19, the members of her future audiences greatly appreciate the

Duchess' anticipatory drama in action. Scholars and theatre enthusiasts

alike should look forward to many more productions hereafter.

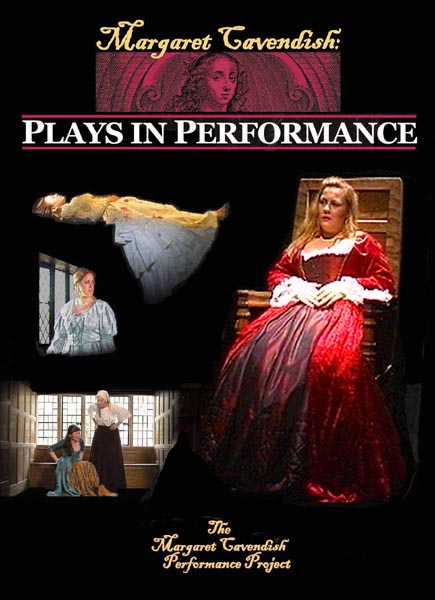

This 3.5 hour DVD includes a contextual introduction to Cavendish's

life and works, an individual introduction to each play, together with commentary

on learning and teaching and production issues. Student participants' insights

into acting and producing Cavendish's plays are also featured. Screen productions

were largely filmed in historic seventeenth century locations in York, England,

courtesy of the National Trust, York Diocese and other friends of the Margaret

Cavendish Performance Project. Production of this DVD was part-funded

by Gweno Williams' National Teaching Fellowship (2002). It is available

in both British and North American DVD formats.