2.

Data

2.

Data 2.

Data

2.

DataAnalysis of any discourse, including SCMC, views the language of the discourse (the text) together with the broader context of its use. A preliminary measure is to summarise the source of the SCMC data in this paper. The term SCMC encompasses a variety of CMC system types, from internet relay chat rooms (IRC), to local area networks (LANs), to multi-user domains (MUDs and MOOs). The data in this paper is from a virtual community dedicated to exploring ways of language learning online.

Webheads is a community of English language learners and teachers which has been meeting solely on the internet since 1998. Participation is entirely free and voluntary. The Webheads environment is a complex intertwining of CMC modes. Members of the group maintain personal web pages on the Webheads site [1], while much interaction takes place on the email list [2]. The more technologically minded members of Webheads frequently experiment with other CMC technology, such as voice conferencing and experimentation with web cams. Webheads has been the subject of a number of short reports, papers and presentations (Stevens, 1999; 2000a; 2000b; 2001; Coghlan and Stevens, 2000; Stevens and Altun, 2001 inter alia). Interviews with Webheads members also figure in a doctoral dissertation (Steele, 2002).

The concern

here is with the Webheads synchronous text-based CMC chats. These are

held weekly at the MOO Tapped In [3] and until mid-2001 were hosted at the graphical MOO

The Palace.[4] Webheads members ? tutors and students ? gather

for informal text-based chat sessions on a wide range of topics. These sessions

are intended primarily for students? language practice and to explore the

use of SCMC technology in language learning. There is a social function, however,

and much communication is phatic communion (Malinowski, [1923] 1999:302):

?? language used in free, aimless, social intercourse ??. The entire set of

data which forms the basis of this paper comprises 150 logs of chat sessions

in the MOOs The Palace and Tapped In and from logs of participation

using the chat software ICQ [?I seek you?] [5]. These logs were originally

saved and archived by members of the Webheads group. Permission was

gained to use the archives for research purposes. These data sources are briefly

sketched below.

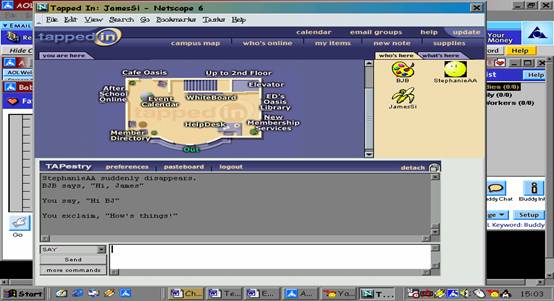

Tapped In describes itself as: ?the online workplace of an international community of education professionals.? It is an online environment where: ?Teachers and librarians, professional development staff, teacher education faculty and students, and researchers engage in professional development programs and informal collaborative activities with colleagues? (from the Tapped In website [3]).

At Tapped

In the text interface is similar to that of a standard text-based synchronous

chat program, and the text of the discourse scrolls up the screen (in plain

text format) as it might in IRC. Navigation around the Tapped In environment

is by simple commands. For example, to join a particular participant somewhere

in Tapped In, the command /join [name] is typed. There is also a javascript-enabled

graphical interface, TAPestry, which allows for the representation of the

space of Tapped In as a ?map of the campus?, around which it is possible

to navigate through mouse clicks.

Figure 1 is a screen shot of the Tapped In interface:

Figure 1: The Tapped In interface

Turns are typed in the white box at the bottom of the frame; when they are sent they appear in the grey box above, which is seen by all participants. Interaction is one way (Herring, 1999; Cherny, 1999:154) in that turns cannot be seen by other participants as they are being typed.

The Palace is a recreational MOO, that describes itself as a ?graphical avatar chat? (from its homepage [4]). The Palace (figure 2) makes yet stronger use of the graphical element by allowing for the creation of movable avatars, or pictorial representations of participants.

Figure 2: The Palace interface

In the main window we see the avatars with their nickname labels. Turns in The Palace are typed in the white box towards the bottom of the screen, and appear in speech bubbles above the appropriate avatar. A log of the text can be viewed in the box on the right of the frame.

The third SCMC system to appear in the data in this paper is ICQ. This chat program is a selective SCMC system in that to interact, participants must be invited to join one another?s list. Thus it is more private than an open IRC system. It is similar to IRC in so far as it is text-only and has no explicit graphical interface. It was created as a ?? technology which would enable the Internet users to locate each other online on the Internet, and to create peer-to-peer communication channels, in a straight forward, easy, and simple manner? (from its homepage [5]). The ICQ text appears in a small window on the screen; as with most SCMC, participants often attend to other tasks in parallel to ?chatting? on ICQ.

There is little reference made to the graphical interface at Tapped In or at The Palace by Webheads participants. However, the multimodal merging of the textual with the graphical with regard to the possibilities for opening other pages and sites creates potential for multi-tasking, for attending to more than one on-screen task at a time. This potential is exploited, and its effects can be witnessed in the text of the discourse, as can be seen in example 1 below:

|

Vance:

hi. I've got Gosia on icq |

|

Brazil:

Who is Gosia ?? |

|

Vance:

Gosia is another student. Are you on icq now? |

|

Brazil:

Is the class finishing ?? |

|

Brazil:

yes I am |

|

Ying-Lan:

@64,64 !It's Ying-Lan |

|

Brazil:

Hi Ying. |

|

Brazil:

We are in ICQ .. Wanna Join us ?? |

Example 1

There are sometimes attempts by Webheads participants (either tutors or students) to specify what is to be discussed, though it is in the nature of SCMC discourse that participants will stray from any prescribed topic. There is a strong ludic vein running through the synchronous text-based chat sessions; word play and the role-playing possibilities of text-based SCMC are evident here as they are in IRC.

It should be borne in mind that when SCMC interaction originally takes place, participants can see the text unfolding on their screens. They are also able to scroll back up the text box on the screen to re-read previous parts of the interaction. Furthermore, a particular feature of one Webheads meeting place, Tapped In, is that transcripts of members? interaction for the duration they are logged on to the system are emailed to them after they log off. These properties raise interesting questions about the relationship of text to discourse. There is a commonplace clear distinction between text and discourse, summarised by Seidlhofer and Widdowson (1999:206), where ?text is the linguistic product of a discourse process.? In the case of spoken discourse analysis, the interaction is usually recorded and transcribed prior to analysis, effectively separating the text from the context. Regarding SCMC, participants have immediate access to the linguistic product of the discourse process. They can read the text (the product) as the interaction (the process) unfolds.

It follows that given the properties of multi-party text-based SCMC, and their departure from the dyadic spoken prototype used in much analysis of conversation, cohesion will be manifest in different ways, and participants will ascribe coherence in different ways, in the written mode. This is so, as we shall see; though there are also striking similarities. It is to coherence and cohesion in SCMC discourse that we turn to next.