Submission

to Discourse Analysis Online

Conversational floors in synchronous text-based CMC discourse

James Simpson

University

of Reading

School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies

Whiteknights

Reading RG6 6AA

j.e.b.simpson@reading.ac.uk

Abstract: This paper presents a study of the discourse characteristics of a virtual community. The data is from the synchronous, or real time, text-based chat forum of Webheads, an internet-based community of learners of English, teachers of English, and others interested in the relationship between language learning and technology. The chat forum is the online meeting place for community members. As such, it is an international site of language use with participants from a range of linguistic backgrounds.

Within this context, some pertinent themes are investigated which relate to a relatively recent form of discourse. Synchronous text-based computer-mediated communication (SCMC) is not a simple hybrid of speech and writing. Rather, speech-like qualities are created by the ability to communicate in writing, in real time, with spatially distant participants in novel social situations.

The discussion centres on the interplay between the technological attributes of the medium, linguistic, discourse and sociocultural conditions within which the participants interact. How do these elements combine to shape the discourse? This question is addressed with reference to the cohesive feature of conversational floor. Because there is a lack of coordination of transfer in the medium, conversational floor emerges as an organising principle in preference to models of conversation based on turn taking.

Three main floor types are discussed and exemplified: the speaker-and-supporter floor, the collaborative floor and the multiple conversational floor. It is further suggested that in addition to the medium-related influences, the development of particular floors is dependent on discourse features such as participant role relations, topic, and communicative action.

Keywords: computer-mediated communication, discourse analysis, conversation analysis, conversational floor, virtual community

1. Introduction

This paper is an investigation into patterns of interaction in synchronous, text-based computer-mediated communication (henceforth SCMC). As with much CMC research, the underlying aim is to contribute to an understanding of the extent to which human interaction is affected by mediation via computers.

The primary motivation for the paper is the recognition of the tendency in multi-participant SCMC discourse for certain notable patterns of interaction ? conversational floors ? to develop. Ultimately the question is addressed as to what factors account for such patterns. In so doing, reference is made to research into multi-party conversation in both the written and spoken mode.

The paper starts with a description of the source of the data, and a comment on the analysis of SCMC discourse. In the following section SCMC is discussed in relation to the fundamental concepts of cohesion and coherence in discourse. Then an approach to cohesion in SCMC, the conversational floor, is described; its elements are outlined, and some of its various manifestations in the discourse text are exemplified. Finally we turn to aspects of the discourse which influence the development of floors: the role relations of the participants; the communicative action and the topic of the discourse; and certain medium-related factors. Their influence is discussed with reference to an extended stretch of SCMC text tracing the development of conversational floors.

2. Data

Analysis of any discourse, including SCMC, views the language of the discourse (the text) together with the broader context of its use. A preliminary measure is to summarise the source of the SCMC data in this paper. The term SCMC encompasses a variety of CMC system types, from internet relay chat rooms (IRC), to local area networks (LANs), to multi-user domains (MUDs and MOOs). The data in this paper is from a virtual community dedicated to exploring ways of language learning online.

Webheads is a community of English language learners and teachers which has been meeting solely on the internet since 1998. Participation is entirely free and voluntary. The Webheads environment is a complex intertwining of CMC modes. Members of the group maintain personal web pages on the Webheads site [1], while much interaction takes place on the email list [2]. The more technologically minded members of Webheads frequently experiment with other CMC technology, such as voice conferencing and experimentation with web cams. Webheads has been the subject of a number of short reports, papers and presentations (Stevens, 1999; 2000a; 2000b; 2001; Coghlan and Stevens, 2000; Stevens and Altun, 2001 inter alia). Interviews with Webheads members also figure in a doctoral dissertation (Steele, 2002).

The concern

here is with the Webheads synchronous text-based CMC chats. These are

held weekly at the MOO Tapped In [3] and until mid-2001 were hosted at the graphical MOO

The Palace.[4] Webheads members ? tutors and students ? gather

for informal text-based chat sessions on a wide range of topics. These sessions

are intended primarily for students? language practice and to explore the

use of SCMC technology in language learning. There is a social function, however,

and much communication is phatic communion (Malinowski, [1923] 1999:302):

?? language used in free, aimless, social intercourse ??. The entire set of

data which forms the basis of this paper comprises 150 logs of chat sessions

in the MOOs The Palace and Tapped In and from logs of participation

using the chat software ICQ [?I seek you?] [5]. These logs were originally

saved and archived by members of the Webheads group. Permission was

gained to use the archives for research purposes. These data sources are briefly

sketched below.

Tapped In describes itself as: ?the online workplace of an international community of education professionals.? It is an online environment where: ?Teachers and librarians, professional development staff, teacher education faculty and students, and researchers engage in professional development programs and informal collaborative activities with colleagues? (from the Tapped In website [3]).

At Tapped

In the text interface is similar to that of a standard text-based synchronous

chat program, and the text of the discourse scrolls up the screen (in plain

text format) as it might in IRC. Navigation around the Tapped In environment

is by simple commands. For example, to join a particular participant somewhere

in Tapped In, the command /join [name] is typed. There is also a javascript-enabled

graphical interface, TAPestry, which allows for the representation of the

space of Tapped In as a ?map of the campus?, around which it is possible

to navigate through mouse clicks.

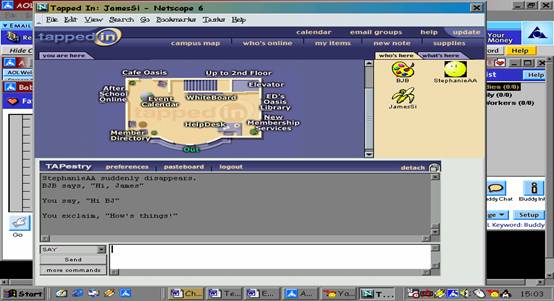

Figure 1 is a screen shot of the Tapped In interface:

Figure 1: The Tapped In interface

Turns are typed in the white box at the bottom of the frame; when they are sent they appear in the grey box above, which is seen by all participants. Interaction is one way (Herring, 1999; Cherny, 1999:154) in that turns cannot be seen by other participants as they are being typed.

The Palace is a recreational MOO, that describes itself as a ?graphical avatar chat? (from its homepage [4]). The Palace (figure 2) makes yet stronger use of the graphical element by allowing for the creation of movable avatars, or pictorial representations of participants.

Figure 2: The Palace interface

In the main window we see the avatars with their nickname labels. Turns in The Palace are typed in the white box towards the bottom of the screen, and appear in speech bubbles above the appropriate avatar. A log of the text can be viewed in the box on the right of the frame.

The third SCMC system to appear in the data in this paper is ICQ. This chat program is a selective SCMC system in that to interact, participants must be invited to join one another?s list. Thus it is more private than an open IRC system. It is similar to IRC in so far as it is text-only and has no explicit graphical interface. It was created as a ?? technology which would enable the Internet users to locate each other online on the Internet, and to create peer-to-peer communication channels, in a straight forward, easy, and simple manner? (from its homepage [5]). The ICQ text appears in a small window on the screen; as with most SCMC, participants often attend to other tasks in parallel to ?chatting? on ICQ.

There is little reference made to the graphical interface at Tapped In or at The Palace by Webheads participants. However, the multimodal merging of the textual with the graphical with regard to the possibilities for opening other pages and sites creates potential for multi-tasking, for attending to more than one on-screen task at a time. This potential is exploited, and its effects can be witnessed in the text of the discourse, as can be seen in example 1 below:

|

Vance:

hi. I've got Gosia on icq |

|

Brazil:

Who is Gosia ?? |

|

Vance:

Gosia is another student. Are you on icq now? |

|

Brazil:

Is the class finishing ?? |

|

Brazil:

yes I am |

|

Ying-Lan:

@64,64 !It's Ying-Lan |

|

Brazil:

Hi Ying. |

|

Brazil:

We are in ICQ .. Wanna Join us ?? |

Example 1

There are sometimes attempts by Webheads participants (either tutors or students) to specify what is to be discussed, though it is in the nature of SCMC discourse that participants will stray from any prescribed topic. There is a strong ludic vein running through the synchronous text-based chat sessions; word play and the role-playing possibilities of text-based SCMC are evident here as they are in IRC.

It should be borne in mind that when SCMC interaction originally takes place, participants can see the text unfolding on their screens. They are also able to scroll back up the text box on the screen to re-read previous parts of the interaction. Furthermore, a particular feature of one Webheads meeting place, Tapped In, is that transcripts of members? interaction for the duration they are logged on to the system are emailed to them after they log off. These properties raise interesting questions about the relationship of text to discourse. There is a commonplace clear distinction between text and discourse, summarised by Seidlhofer and Widdowson (1999:206), where ?text is the linguistic product of a discourse process.? In the case of spoken discourse analysis, the interaction is usually recorded and transcribed prior to analysis, effectively separating the text from the context. Regarding SCMC, participants have immediate access to the linguistic product of the discourse process. They can read the text (the product) as the interaction (the process) unfolds.

It follows that given the properties of multi-party text-based SCMC, and their departure from the dyadic spoken prototype used in much analysis of conversation, cohesion will be manifest in different ways, and participants will ascribe coherence in different ways, in the written mode. This is so, as we shall see; though there are also striking similarities. It is to coherence and cohesion in SCMC discourse that we turn to next.

3. Coherence and cohesion in written conversation

Here is an example of interaction in a stretch of discourse text from the data source outlined above:

|

OritK

has arrived. |

|

OritK's

personal recorder (recording) has arrived. |

|

OritK

goes OUT. |

|

OritK's

personal recorder (recording) goes OUT. |

|

MargaretD

exclaims, "he likes coming and going!" |

|

rif

[guest] exclaims, "I need to leave guys. It was all nice to see

friends and say hi!" |

|

SusanneN

says, "I guess he is a student practicing before class." |

|

VanceS

says, "Lian is talking about a 30 day bicycle trip she is going

to make with her school mates next summer" |

|

MargaretD

exclaims, "ByeRif!" |

Example 2

Five

different participants (six including OrtiK?s personal recorder) take nine

turns, some of which are in the third person. Participants enter and exit..

Seemingly unrelated turns are juxtaposed with one another. A number of conversations

run in parallel It is these interaction patterns ? the interleaved threads

of conversation ? which are considered broadly as a feature of cohesion. Cohesion

contributes to the coherence of the discourse by being the ?actual forms of

linguistic linkage? (Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik,

1985:1425), that is to say, the linguistic manifestation of coherence.

This section explains why cohesion in SCMC operates in different ways to cohesion in spoken discourse. In subsequent sections conversational threads as they relate to certain types of conversational floor are considered more relevant to an SCMC account of cohesion and coherence in the discourse.

The issue of coherence is central to the study of discourse. Cook?s (1989:4) definition of coherence is: ?? the property of being unified and meaningful.? Discourse analysis itself is defined by Cook (ibid.:14) as: ?? the search for the answer to the problem of what gives stretches of language unity and meaning.? This is to say, discourse analysis is dedicated to discovering what makes language in use coherent for those who use it.

In this section coherence and cohesion are discussed with reference to SCMC discourse. It is suggested that both for participation in and analysis of SCMC discourse, cohesion is not dependent on the coordination of transfer in turn-taking, as it would be in spoken discourse. Rather, broader and looser constructs such as the conversational floor, as described in following sections, are the cohesive ?glue? that contribute towards participants? ascribing coherence (unity, meaning) to the discourse. In examples 1 and 2 above, for instance, coherence was not achieved through an adherence to the same principles of conversational interaction as apply to much spoken discourse.

The search for coherence, in whatever discourse type, and whether by the participants or by analysts, is an interpretive process. It is said that coherence is ?in the eye of the beholder? (Bublitz and Lenk, 1999). In SCMC discourse we certainly appeal to linguistic form at clause level (lexis and syntax) to aid us in the process of ascertaining what gives language in use coherence. On a broader inter-turn level, as with spoken discourse, the formal surface connective linkages of text ? lexical and referential cohesion (Halliday and Hasan, 1976) ? go some way to explaining how a text is coherent. In one-way SCMC discourse of the type described here, such inter-turn cohesion as it exists in spoken discourse is often not readily apparent. However, it is participants who ultimately accord meaning and unity to the text in the discourse process, and they evidently manage to do so. The discourse of SCMC is coherent for its participants; if it were not, it would not be so popular, as noted by Herring (1999).

A token of the lack of cohesion in turn taking ? what Herring (1999) calls the lack of sequential coherence ? is the resultant disrupted turn adjacency (Herring, ibid.). The example below is a typical instance of disrupted turn adjacency. Here and in subsequent examples, turns have been numbered for ease of reference.

|

1 |

MichaelC:

Good evening Ying. How are things? |

|

2 |

Ying-Lan:

Not so good. |

|

3 |

Ying-Lan:

I took a test this morning. |

|

4 |

MichaelC:

What's wrong? |

Example 3

In comparison with spoken conversation, written conversation displays a reduced sensitivity to coordination of transfer in turn-taking. This can be viewed as a lack of fine tuning.

A number of commentators on linguistic features of SCMC note the dissimilarity of turn-taking patterns in SCMC and in spoken discourse. Cherny (1999) and Herring (1999) discuss these differences in detail. Chun?s (1994:26) remark is illustrative of the view that turn-taking in SCMC is entirely unlike that in spoken discourse: ?In terms of discourse management during a discussion, turn-taking as done in spoken conversation is not a factor in CACD [computer-assisted class discussion].? Kitade (2000:149) notes that there is ?no turn-taking competition? in SCMC.

The lack of fine-tuning in SCMC turn-taking is the responsibility of two fundamental facts of this type of discourse: 1) turns cannot be seen until they are sent; and 2) the visual and auditory (paralinguistic and prosodic) cues which in spoken discourse underpin the turn-taking system are missing. The consequence is disrupted turn adjacency. Herring describes disrupted turn adjacency in SCMC (1999:3): ?? a message may be separated in linear order from a previous message it is responding to, if another message or messages happen to have been sent in the meantime.? And in an early study of SCMC, Murray (1988) notes that: ?? the sender may make a second move before receiving a response to the first and a message may interrupt a turn.?

In the stretch of text in example 3 above, turns 1 and 2 follow the pattern of an adjacency pair (Schegloff and Sacks, 1973). In an adjacency pair the relationship between the first and second pair parts is one of conditional relevance (Schegloff, [1968] 1972). Put simply, the presence of the first pair part is said to open a slot in conversation for an expected, or conditionally relevant, second pair part. MichaelC?s first pair part (turn 1) is followed by the second pair part (2) from Ying-Lan. This response, ?not so good?, is a dispreferred response (Heritage, 1984:265-269; Nofsinger, 1991:71-2). That is to say, although the response is expected, or conditionally relevant, it is not as expected (or preferred) as a response such as ?I?m fine thanks?. Following a tendency noted in dispreferred second pair parts, the response is followed by an elaboration in turn 3. But MichaelC?s next turn (4) seems to be in response to Ying-Lan?s turn 2 rather than turn 3. This is a case of disrupted turn adjacency.

The disrupted turn adjacency in this extract may well be a result of reduced coordination of transfer in that MichaelC was typing turn 4 at the same time as Ying-Lan was typing her elaboration following her dispreferred response (turn 3); it happened that they sent their turns at about the same time, but Ying-Lan sent her turn fractionally before MichaelC sent his. Thus it appears in the log of the chat, and appeared at the time on the screen, that Ying-Lan answers MichaelC?s question before he asks it.

An alternative, and rather problematic, possibility is that the turns appeared in different orders on different computer screens. When considering the technology of SCMC we should recall that not all aspects of the discourse setting are shared. Individual computers have varying levels of processing power. Internet connections have different speeds. Turns thus potentially arrive on different screens in different orders. Evidence of this phenomenon ? system-related disrupted turn adjacency, or lag (Herring, 1999) ? can be seen in the following stretch of SCMC discourse text recorded on ICQ:

|

1 |

<ying>

We hope our government will be better in the future. |

|

2 |

<Mad>

really bad karma then. |

|

3 |

<ying>

Who is Gerald Ford? |

|

4 |

<Vance>

What were his words? Why did he have to land in an elementary school?

Yeah, not a good choice. Sounds like something Gerald Ford would have

done. But he was harmless. |

|

5 |

<Vance>

He was a preseident of the USA who was prone to accidents. |

Example 4

ying poses the question (turn 3) ?Who is Gerald Ford?? before, it seems, any mention of Gerald Ford has entered the conversation. We can assume that Vance and ying?s turns appeared in the logical sequence on their own screens but, because of a system delay, appear in the logs in reverse order.

We cannot be certain how common a system-related disrupted turn adjacency is. Unless there is some explicit reference to a later turn, the explanation for disrupted turn adjacency might equally be the first posited above: that turns were being written at the same time, and one was posted fractionally before the other (thus appears out of place).

On a broader level, these observations on disrupted turn adjacency tend to support the view that applying models of turn-taking in spoken conversation directly to SCMC discourse is not profitable. For the remainder of this paper, we turn our attention to an alternative perception of cohesion: the conversational floor.

4. Floors in spoken and written conversation

4.1 Background

A detailed

treatment of the notion of floor in synchronous CMC is found in Cherny (1999).

She states (1999:174):

Given

that there is no competition for the [MOO] channel per se, but rather competition

for attention or control of the discourse, notions of shared or collaborative

floor seem to be more helpful than the standard turn-taking literature. These

notions also appear more useful for theorising multi-threaded topic discourse.

Cherny

has found that work on floors of conversation in multi-party spoken discourse

was helpful in developing her categorisation of floor types in a MOO. And

on the face of it, multi-party SCMC discourse bears more similarity to the

fluid threads of dinner party conversation or discussion groups than to the

two-party conversation which is the foundation of much spoken conversation

analysis.

In

her review of early conversation analysis work on turn taking and floor of

conversation, Edelsky (1981) reveals that frequently no distinction was made

between floor and turn, though in any multi-party discourse such a distinction

is vital. Stenstrom?s

(1994:34) definition of the turn as: ?? everything A says before B takes over,

and vice versa? is crude but entirely workable in SCMC, a discourse environment

where turns cannot be co-constructed and where there is no overlap. It is

a technical definition with little ambiguity. Definition of the floor is less

clear-cut, dependent as it is upon inferring how participants themselves viewed

the unfolding discourse. For such a definition, we first turn to Edelsky (1981:405):

The floor is defined as the acknowledged

what?s-going-on within a psychological time/space. What?s going on can be

the development of a topic or a function (teasing, soliciting a response,

etc.) or an interaction of the two. It can be developed or controlled by one

person at a time or by several simultaneously or in quick succession. It is

official or acknowledged in that, if questioned, participants could describe

what?s going on as ?he?s talking about grades? or ?she?s making a suggestion?

or ?we?re all answering her.?

A

reading of Edelsky suggests that there are three definable elements to the

floor: (1) the topic, the aboutness of the discourse; (2) the communicative

action: how things are being said in the discourse; and (3) the

participants? sense of what is happening in the conversation. From

the analyst?s point of view, these are each evident only to the extent to

which they can be inferred from the text. This constraint should be acknowledged

as a caveat in a discussion of floor. Nonetheless, the text of SCMC allows

an analyst to gain a closer participant?s sense of what was going on than,

for example, a transcription of spoken discourse. This is because the participants

themselves are denied the range of visual and aural feedback cues; any ratification

must ipso facto appear in the text itself, as we see below.

4.2

Floor ratification in SCMC

?Simply

talking, in itself, does not constitute having the floor,? say Shultz, Florio

and Erikson (1982:95). ?The ?floor? is interactionally produced, in that speakers

and hearers must work together at maintaining it.? Thus one can be the speaker

but not hold the floor. In her study of floor and gender patterns in asynchronous

CMC discourse, Herring (forthcoming) supports Edelsky?s assertion that to

be a floor-holding turn, it must be ratified by other participants. In spoken

discourse, such ratification can be done verbally or through non-verbal nods

and backchannels. In the examples below, we see that in SCMC floor ratification

can also be done verbally or through responses which are representations of

non-verbal behaviour.

In

example 5 Vance (turns 1, 2 and 4) is holding the floor; ratification is done

by BJB (turn 3) and SusanneN (turn 4) through their verbal responses.

|

1 |

VanceS

says, "I go to Guangchow and get Maggie (she needs a travel partner

to travel in the summer)" |

|

2 |

VanceS

says, "Then we go visit Moral in Kunming" |

|

3 |

BJB

exclaims, "sounds like fun, Vance!" |

|

4 |

VanceS

says, "Then to Wuhan ot visit Lian (2000 km)" |

|

5 |

SusanneN

says, "Oh really, sounds exciting." |

Example 5

In

example 6 BJB ratifies Susanne?s turn with a ?nod?. This is an action,

a turn sent in the third person to represent non-verbal behaviour:

|

1 |

SusanneN

asks, "Really, Minsk is closer to us in Europe than Pennsylvania,

I guess?" |

|

2 |

BJB

[HelpDesk] nods |

Example 6

Floor

ratification by members of the Webheads group has the dual purpose

of signalling both that the participant is paying attention to the floor holder

and that they comprehend what has been written. In her investigation into

backchannel responses in a MOO, Cherny (1999:194) similarly maintains that:

?? it is difficult if not impossible to separate affect out from the back

channel function in this medium, since an appropriate emotional response to

a turn (e.g., a laugh) indicates both attention and understanding just as

well as a nod does.?

In

multi-party SCMC discourse, problems arise with floor ratification being misdirected

or mistaken. In example 7 below, Maggi?s response (turn 4) to Gold10?s turn

(1) is misinterpreted by Ying in turn 5 as a ratification of her turns 2 and

3:

|

1 |

gold10:

Is here a lession about reading or writing? |

|

2 |

Ying-Lan:

They were worry about the world,,, we will be worry about the computer.

|

|

3 |

Ying-Lan:

^not will be... we are worry about the computer. |

|

4 |

Maggi:

which do you prefer? |

|

5 |

Ying-Lan:

prefer what? |

|

6 |

Maggi:

no, we are worrying about the computer |

|

7 |

gold10:

what will be taught at section 7? |

|

8 |

Maggi:

I meant Gold Ying... |

Example 7

Turns

are directed in SCMC by naming the participant to which they are addressed.

This SCMC-specific cohesive device of cross-turn reference (Herring,

1999) or addressivity (Werry, 1996) is used by Maggi in turn 8 of example

7 to repair the misunderstanding above. In other cases, as with example 8

below, addressivity is included in the original floor-holding and floor-ratifying

turns (turns 1 and 4). This can be considered a navigation technique in response

to the fact that there are a number of participants.

|

1 |

SusanneN

[to Maggie]: "A webhead, has a lot of furry hair, and a fuzzy old

jacket, thick glasses and is all pale because of the lack of daylight,

plus pimlpes due to unhealthy snacks and black coffeee?" |

|

2 |

PhilB

says, "Margaret - that's right! Jacket & tie become mandatory

pedagogical accessories." |

|

3 |

JohnSte

says, "Back when I was a Department chair, my dress code was shorts

and a tee-shirt." |

|

4 |

MargaretD

exclaims, "ROTFL at Susanne description!" |

Example 8

Again,

ratification is carried out by a representation of non-verbal behaviour: ROTFL

is SCMC shorthand for ?rolling on the floor laughing?.

4.3

Participant structure and floor types

Research

into conversational floors in CMC discourse has quite naturally concentrated

on applying and testing findings from analysis of multi-party spoken conversation.

Edelsky?s (1981) research into floors and gender in spoken conversation identified

two types of floor: a singly developed floor (F1) and one which is a ?collaborative

venture? (F2). F1?s are: ?? characterised by monologues, single-party control

and hierarchical interaction where turn takers stand out from non-turn takers

and floors are won or lost ?? (Edelsky, 1981:416). F2?s are: ?? inherently

more informal, cooperative ventures ?? (ibid.). Herring (forthcoming)

found that these two floor types were evident in her study of asynchronous

CMC discourse on two discussion boards.

Missing

from Edelsky?s bipartite distinction are instances where two or more floors

of conversation are continuing in parallel. A broader classification deriving

from research into dinner table conversation and classroom discourse by Shultz

et al. (1982) (also in Erikson and Shultz, 1977) posits categories

of participation structure where floors are single or multiple. Though there

are further sub-divisions in this classification, single floors are, broadly

speaking, correspondent with Edelsky?s F1 and F2: a single speaker, with a

number of attenders; or a floor which is more collective or collaborative.

Multiple floors, type IV participation structure in the typology of Shultz

et al., are described by these authors (1982:102) as having: ?? subgroups

of the persons present participating in topically distinct simultaneous conversations.?

The

summary grouping of floor types by Hayashi (1991) draws on the findings of

Shultz et al. and Edelsky. Hayashi also divides floor types into single

conversational floors and multiple conversational floors, and also subdivides

the single floor type into the single person floor and the collaborative floor.

Further sub-categorisations are described, based on relative levels of interaction.

Hayashi?s system is adapted by Cherny (1999:176ff) to describe floor types

in MOO discourse. Within the context of the Webheads SCMC described

here, identification of these floors is straightforward enough, suggesting

a similarity of floor structure across contexts of synchronous CMC use. Leaving

aside some of the less common patterns, three habitually occurring floor types

are described and illustrated below: the speaker-and-supporter floor; the

collaborative floor; and the multiple conversational floor.

4.4

Speaker-and-supporter floor

The

speaker-and-supporter floor is a single conversational floor. One participant

can be regarded as the floor holder, and others are supporting through the

use of back-channel devices and other short interjections. In this example

(9), Vance is holding the floor; his short turns are interspersed by the occasional

supporting comment, question and back-channel from Maggie and Ying-Lan:

|

1 |

Vance:

Go to this url: http://www.geocities.com/members/tools/file_manager.html |

|

2 |

Vance:

You might want to bookmark that url. |

|

3 |

Vance:

You can't use it just yet. |

|

4 |

Vance:

But you'll want to come here later: http://www.geocities.com/members/tools/file_manager.html |

|

5 |

Ying-Lan:

^why? |

|

6 |

Vance:

Geocities will now email you a password. |

|

7 |

Maggi:

Hey, I'm getting the hang of this. |

|

8 |

Ying-Lan:

^I got it. |

|

9 |

Maggi:

great... |

|

10 |

Vance:

You got the password? |

|

11 |

Ying-Lan:

^yes |

|

12 |

Ying-Lan:

^I am a member of geocities.com now |

|

13 |

Vance:

Great. OK, you can enter the file manager. |

|

14 |

Ying-Lan:

^My email address is yinglan@geocities.com |

|

15 |

Vance:

Go to that url and press the Enter the File Manager button. |

|

16 |

Vance:

You will be asked for your user name and password. |

|

17 |

Vance:

Your user name is yinglan and your password is whatever they sent you. |

|

18 |

Maggi:

sorry, I accidently clicked on the films... |

|

19 |

Vance:

Here's what you have to do next: |

|

20 |

Vance:

When you visit your new url, you will see the file index.html by default. |

|

21 |

Maggi:

ok |

|

22 |

Vance:

Geocities created an index.html file for you. If you put in your url

you'll see it. |

|

23 |

Maggi:

ok |

|

24 |

Vance:

What you want to do now is replace that file with your own, which has

to be called index.html |

|

25 |

Maggi:

ok |

|

26 |

Vance:

So you create a little web site. The introductory page to your site

is called index.html. And you just upload the files to your server space

using the file manager. |

|

27 |

Maggi:

neat!!!1111t |

|

28 |

Vance:

I make my web sites in ms Word. I just start a document, save it as

html, and link it to other documents. |

|

29 |

Maggi:

a whole lot easier than I thought!!!!!!!!!! |

Example 9

4.5

Collaborative floor

The

single floor is constructed by a number of participants. In this example (10)

Ying-Lan, Vance and Maggi co-construct the collaborative floor:

|

1 |

Ying-Lan:

How long will you take your vacation? |

|

2 |

Ying-Lan:

Sounds nice. |

|

3 |

Vance:

I will take 6 days for my vacation. |

|

4 |

Vance:

But it's not a vacation, really. |

|

5 |

Ying-Lan:

You will go alone? |

|

6 |

Vance:

I will be in Europe alone but my son will fly to New York and camp out

|

|

7 |

in

my hotel room. |

|

8 |

Ying-Lan:

You son who lives in California? |

|

9 |

Vance:

Yes, he's never been to New York City before. |

|

10 |

Maggi:

Be sure the mini bar is stocked with snacks... |

|

11 |

Vance:

No way, I'll stock up at the deli. |

|

12 |

Vance:

He's been trained to stay out of mini bars in upscale hotels. |

|

13 |

Maggi:

That's a good place to start... |

|

14 |

Vance:

The mini bar? |

|

15 |

Maggi:

no...the deli's |

|

16 |

Ying-Lan:

^New York is a big city ... why do you call her as "Big Apple"? |

|

17 |

Maggi:

...best in the world |

|

18 |

Vance:

Good question! |

|

19 |

Maggi:

Has to do with jazz Ying... |

|

20 |

Maggi:

or at least one story does... |

|

21 |

Vance:

Does it? |

|

22 |

Ying-Lan:

Has to do with Jazz? |

|

23 |

Ying-Lan:

one story? |

|

24 |

Maggi:

Yes...remember I was born in New York... |

Example 10

4.6

Multiple conversational floor

When

two or more floors exist in parallel, a multiple conversational floor is evident.

In the following stretch of twelve turns (example11), the floors have been

identified and labelled by their primary feature, topic. Five turns are associated

with the topic of thanksgiving (floor A), while seven relate to discussion

of the TOEFL test (floor B):

|

1 |

A |

Ying

[guest] says, "Hi.. everyone.. it is a little late to say "Happy

Thankgiving!"" |

|

2 |

A |

sara

[guest] says, "hi ying" |

|

3 |

B |

SusanneN

[to Sara [guest]]: "the TOEFL Exam tomorrow, how can we help you

prepare for that?" |

|

4 |

A |

Ying

[guest] asks, "How was your turkey at the table?" |

|

5 |

B |

sara

[guest] says, "i have one practice i will do it later" |

|

6 |

B |

Ying

[guest] asks, "Toefl Exam?" |

|

7 |

B |

sara

[guest] says, "yes" |

|

8 |

A |

SusanneN

asks, "And vance, how was the turkey outing with your Spanish friends?" |

|

9 |

B |

SusanneN

says, "it is the Test Of Englsih as a Foreign Language" |

|

10 |

B |

Ying

[guest] says, "I knew that." |

|

11 |

A |

BJB

[to Ying [guest]]: "it is never to late to say happy Thanksgiving...we

all have so much to be thankful for!" |

|

12 |

B |

SusanneN

[helpdesk] smiles to Ying I just learnt a new acronym. |

Example 11

Within

a multiple conversational floor, as Cherny (1999:176) notes, there can be

a main floor and side floors, or there can be two or more main floors running

in parallel. In SCMC discourse it is possible for an individual participant

to be involved in more than one floor of conversation. In the above example

of a multiple conversational floor, three of the four participants contribute

to both floors. This tendency of the proficient SCMC participant to switch

between floors is an echo of other traits of CMC use. for example, multitasking

? attending to a number of different on-screen activities at once ? is commonplace

(Jones, 2002). And in SCMC, participants are known to cycle between on-screen

identities which they have created (Turkle, 1995).

It

may be noted that in example 9 above (the speaker-and-supporter floor), one

participant was explaining to others how to do something ? in this case, how

to build a website. This is in contrast to the pattern in example 10 (the

collaborative floor). Here, the participants could be said to be ?chatting?,

which is, after all, the prototypical activity in a chat room. In the following

section, we ask whether floor development is shaped by the relationships of

the participants and the topic and purpose of the conversation, and the computer-mediated

nature of the discourse.

5.

Accounting for floor development

Many

factors may influence the development of particular floor types. Here we outline

three contextual aspects of the discourse which shape floor development: participants

and their roles within the group; verbal activity (topic and communicative

action); and a selection of medium-related features. The effects of these

are then investigated with reference to examples of the floor types outlined

in part four. These occur within a single stretch of SCMC discourse text.

5.1

Participant roles

Both

Edelsky (1981) and Herring (forthcoming) concentrate on gender as key contextual

aspects of floor development. Edelsky is careful to note that the F1 and F2

floor types are gender-independent, though participation by men in F1 floors

was far greater than participation by women (1981:415). Herring concludes

that her findings are of two gender styles rather than two different floor

types: a male style associated with individual power and a female style associated

with accommodation to others (forthcoming:18). In the discourse of the virtual

community in question here, Webheads, the status of the participants

and their various role relations may be more influential than gender in shaping

floor structure. A primary though troublesome distinction is between expert

user teachers of English on one hand, and learners of English on the other.

The term expert user is used in preference to the term native speaker

for the obvious reason that expert users of a language are not necessarily

native speakers. For discussion of this and other issues surrounding the notion

of the ?native speaker? see Rampton (1990). Though there are students and

tutors in the Webheads group, care is taken to minimise any perceived

divide. Nonetheless, the role of participant as learner, as tutor, or as other

interested party (e.g., help-desk volunteer; researcher) is often, though

not always, clear. Incidentally, Webheads ?learners? are sometimes

English language teachers in off-screen life. Another distinction may be made

between the more and the less technologically able, or electronically literate

members of the group, regardless of their level of English. Proficiency in

English does not automatically confer proficiency in the use of the technologies

of CMC, as any first-time visitor to an internet chat room will testify. Thus

a proficient technophile may find him- or herself cast in the role of tutor,

but tutor in the use of the technologies of electronic literacy.

There

is a growing body of research on role relations in virtual communities. See,

for example, Cherny (1999) on life in a MUD community; Turkle (1995) on roles

and identity on-screen, and Smith and Kollock?s (1999) collection of papers

on online communities. On the subject of the roles of language teachers and

students face-to-face and online, see Salmon (2000); Kern (1995); Warschauer

(1996; 1999).

5.2

Verbal activity and topic

The

research of Shultz et al. (1982) showed that floor patterns were associated

with the speech activity, and that changes in floor patterns occurred when

the speech activity changed. ?Speech activities?, say Shultz et al. (1982:96),

are: ?units of discourse in conversation that are longer than a sentence and

may consist of one discourse topic, or may consist of a set of connected topics

and subtopics.? The term speech activity is from Gumperz (1977) and

is a synthesis of the current communicative action and the broad topic of

the conversation, for example, ?discussing politics?; ?chatting about the

weather? (Gumperz, 1977:206). The communicative action is the name given to

the type of conversation which might be happening at any time, for example

chatting, explaining, discussing, or arguing.

Shultz

et al., when making the important link between conversational floor

patterns and speech activity, found that certain types of speech activity

often corresponded with certain types of floor. That is to say, when the speech

activity was ?chatting about how much everything costs in the stores nowadays?,

the appropriate floor was a multiple conversational floor with overlapping

speech. And when the speech activity was ?explaining why and where the father?is

going out of town?? there is only one floor, where the parents are the primary

speakers (Shultz et al, 1982: 97). Because SCMC is written rather than

spoken, the term verbal activity is used here in preference to speech

activity.

The

floor, then, is not defined by topic, or aboutness, alone. This

is partly, but not entirely, because topics and their boundaries themselves

are such difficult things to identify. As Brown and Yule do, we can

consider topic as ?what is being talked about?(1983:71). In addition, Brown

and Yule explain that within a broad topic framework there are elements of

personal ?speaker?s topics?. By considering speaker?s topic, they recognise

that within a particular framework where the general topic may be generally

or loosely agreed, the individual participants sometimes have differing views

on what the topic is or where the focus should be. When investigating speaker?s

topic, text of discourse is analysed: ?? not in terms of how we would characterise

the participants? shared information, but in terms of a process in which each

participant expresses a personal topic within the general topic framework

as a whole? (1983:88).

Topics frequently drift; that is, they move gradually from one area into others, without an easily discernible topic boundary. Topic drift, or shading, as a feature of spoken conversation has been commented on by Hobbs (1990), Schegloff and Sacks (1973) and Jefferson (1984) among others. In SCMC rapid topic drift - or topic decay - is the subject of work by Herring and Nix (1997).

The broad

topic itself as it relates to focus of attention is a concern here. In the

Webheads SCMC sessions, it is common for a learner to explicitly raise

a language learning point. When the topic of the discourse is so obviously

related to the acquisition of the L2 (English), it is expected that attention

would be focused towards that floor of conversation. It is also common for

a participant (and no distinction is made here between learners and tutors)

to discuss an aspect of the technologies of SCMC. Particular floor patterns

are associated with topics relating to the development of second or foreign

language skills and with topics relating to the development of electronic

literacy skills. This is demonstrated and explained in the analysis and discussion

below.

5.3

Medium-related factors

There

are also medium-related reasons for particular floors to develop in SCMC.

In particular, the emergence of the multiple conversational floor may be associated

with the way in which a written conversation occurs. Cherny (1999:180) maintains

that: ?Multiple participant floors are in fact easier to achieve [in SCMC

discourse] than they are in face-to-face conversations.? She claims this is

due to the lack of overlap (i.e. the inability to co-construct turns)

in the medium. We might also note that the ability to scroll up and re-read

previous turns, coupled with the slower speed of the unfolding discourse compared

to spoken conversation, facilitate the emergence of multiple floors, and enable

an individual to participate in a number of floors simultaneously.

Topics in SCMC are prone to recur, leading to the re-emergence of particular floor types. This is the case when participants are carrying out more than one on-screen activity. That is to say, when they are multitasking. At certain points in the discourse something happens in another space on the internet which is relevant to a previous topic which then over-rides the current topics. The floor type may consequently revert to a previous one.

5.4 Analysis and discussion: Floor development

This

discussion is based on a stretch of SCMC discourse text of 36 turns in length,

presented below as example 12:

|

1 |

VanceS

says, "I never knew what chili was exactly before" |

|

2 |

BJB

. o O ( that will open a web window to go with your text client ) |

|

3 |

LianA

says, "come to china, then you will know what it is, vance." |

|

4 |

BJB

. o O ( I hope ) |

|

5 |

LianA

oO |

|

6 |

PhilB

says, "Vance, there's a lot of confusion between the words "chili"

and "chile" (borrowed from Spanish." |

|

7 |

Sue

[guest] asks, "Lian, how much did you take on GRE?" |

|

8 |

LianA

asks, "what does burn the scandle from the two ends mean? who can

help?" |

|

9 |

LianA

says, "not very high, only 2160" |

|

10 |

BJB

[to Lian]: "how long do you think a candle will last if you burn

both ends?" |

|

11 |

LianA

says, "nol not candle but scandle" |

|

12 |

LianA

says, "no---typo" |

|

13 |

Sue

[guest] says, "so hight? i am wondering i can only take 1500" |

|

14 |

PhilB

says, "Lian, it's a play on words." |

|

15 |

VanceS

says, "I've been to China several times, but never to Wuhan" |

|

16 |

LianA

says, "it said if you burn the scandle from 2 ends, you will be

a busy man." |

|

17 |

BJB

thinks there are several threads to this conversation |

|

18 |

VanceS

says, "Also you will burn yourself out" |

|

19 |

LianA

says, "welcome vance to wuhan next time to china." |

|

20 |

PhilB

says, "Normally to "burn the candle on both ends" means

to work so much you tire yourself out. With "scandal" instead

of "candle" it sounds like Bill Clinton with his hot interns.

<g>" |

|

21 |

BJB

chuckles. Same result, though. |

|

22 |

VanceS

. o O ( this is a normal consequence of multitasking ) |

|

23 |

VanceS

says, "he must have had too many hot interns in the fire" |

|

24 |

LianA

giggles |

|

25 |

PhilB

asks, "Hey, I found a new free resource called "stuffincommon

virtual communities". Anyone heard of it?" |

|

26 |

VanceS

says, "never" |

|

27 |

Sue

[guest] says, "no" |

|

28 |

LianA

says, "no" |

|

29 |

PhilB

asks, "Wanna see?" |

|

30 |

VanceS

says, "sure" |

|

31 |

Sue

[guest] says, "sure" |

|

32 |

PhilB

says, "It has chat, tools, and a neat whiteboard." |

|

33 |

LianA

says, "yes." |

|

34 |

PhilB

asks, "I'm going to project. Sue, Lian, do you know about projections?" |

|

35 |

LianA

says, "yes" |

|

36 |

Sue

[guest] says, "not sure" |

Example 12

There

are three distinct phases to this stretch of SCMC text:

Turns

1-22: a period where a number of conversations continue simultaneously (a

multiple conversational floor);

Turns

8-24: a period where there is one main conversation where many participants

hold the floor (a collaborative floor);

Turns

25-36: a period where one participant is the floor holder, supported by others

(a speaker-and-supporter floor).

It

will be immediately noted that the first and second phases overlap considerably,

while there is a clear boundary between the second and third phases. Floor

boundaries in SCMC are not necessarily distinct. On this occasion, a collaborative

floor is the main floor in a multiple conversational floor; when the other

conversations in the multiple floor are completed, it becomes briefly the

only floor in a single collaborative floor. Here the multiple floor continues

from turn 1 to turn 22. The floor which emerges at turn 8 becomes the main

floor. At turn 23 it becomes the only floor, as previous conversations are

completed. At turn 25 the pattern shifts decisively to a single speaker-and-supporter

floor.

An

analytical technique for discussing floors in SCMC is to isolate individual

conversations from the text. Naturally, the objection to this might be: how

can we know post hoc and without being informed by the participants

which turns belong to which conversation? The answer must be

that we cannot be certain. Nonetheless, despite the possibility of there being

other interpretations, it seems quite clear that all but one turn (turn 5)

can be accounted for in the way described below.

In

examples 12a to 12f the individual floors and elements of floors in the stretch

of SCMC discourse presented above as example 12 are discussed with reference

to the features which can be said to influence floor development. Before we

turn to these isolated sections, there are three points to note. Firstly,

this stretch of discourse text is not a complete textual record of the interaction.

The log was originally recorded by VanceS, and begins 40 turns after his arrival

at Tapped In. However, the other participants had already commenced

the interaction. Thus some of the conversations in the example are incomplete;

either because they had started before the extract begins, or because they

continue after it ends. The example contains no instances of a participant

entering or leaving the conversation. An illuminating study of openings in

SCMC can be found in Rintel, Mulholland, and Pittam (2001). Secondly, it should

be recalled that the disrupted turn adjacency inherent in the medium gives

a certain arbitrariness to the position of the individual turns in the text

in relation to the other turns. Thirdly, we should also briefly note some

relevant contextual details about the participants:

VanceS is the founder tutor of the Webheads group.

BJB works as a volunteer on the helpdesk at Tapped In.

PhilB is an English teacher who coordinates another group at Tapped In.

LianA and Sue are English language learners with Webheads.

In

example 12a, the turns of Vance, LianA and PhilB belong to the end of the

same conversation, a collaborative floor within a multiple conversational

floor which has the verbal activity chatting about chilli and China.

The discussion about chilli had been continuing for a number of turns before

the beginning of this extract.

|

1 |

VanceS

says, "I never knew what chili was exactly before" |

|

|

|

|

3 |

LianA

says, "come to china, then you will know what it is, vance." |

|

|

|

|

6 |

PhilB

says, "Vance, there's a lot of confusion between the words "chili"

and "chile" (borrowed from Spanish." |

|

|

|

|

15 |

VanceS

says, "I've been to China several times, but never to Wuhan" |

Example 12a

Contextual and temporal aspects of the discourse would suggest that much attention is paid to personal speaker?s topic (writer?s topic?) in SCMC. In example 12a above, within a broad topic framework which could be said to be about chilli, LianA?s speaker?s topic is China. This also becomes Vance?s speaker?s topic in turn 15; a topic drift has taken place within a floor of conversation. Neither the topic of chilli or of China are developed any further in the interaction.

In Example 12b we see the end of another conversation. BJB has been explaining to Sue how to open the graphical interface of Tapped In:

|

2 |

BJB

. o O ( that will open a web window to go with your text client ) |

|

|

|

|

4 |

BJB

. o O ( I hope ) |

Example 12b

We

note that BJB is using a device whereby her turn is displayed inside an ASCII

?thinks? bubble. This is done in Tapped In by prefacing the turn with

the command ?/thinks?. We might infer that she uses this technique because

the turns are directed towards only one among many participants. It is possible

in Tapped In to send a turn privately to another participant using

the ?/whisper? command. That BJB does not do this suggests, in the light of

her role with Tapped In, that she feels the information might be of

use to more than one participant.

Example

12c is an exchange of three turns spread over seven turns of the extract.

|

7 |

Sue

[guest] asks, "Lian, how much did you take on GRE?" |

|

|

|

|

9 |

LianA

says, "not very high, only 2160" |

|

|

|

|

13 |

Sue

[guest] says, "so hight? i am wondering i can only take 1500" |

Example 12c

The

two language learners here are discussing an English language test. Although

not proficient in English, they are both adept at SCMC discourse. Both Sue

and LianA participate in more than one conversation in this extract; turns

by LianA appear in four of the six isolated examples highlighted here.

Example

12d is an aside:

|

17 |

BJB

thinks there are several threads to this conversation |

|

|

|

|

22 |

VanceS

. o O ( this is a normal consequence of multitasking ) |

Example 12d

The topic

here is the conversation itself. In spoken discourse the turns would be expected

to appear together, as an adjacency pair or as the initiation and response

of an exchange. However, here in SCMC they are separated by four unrelated

turns. Also of note is the fact that BJB?s turn is posted in the third person

as an emote or metacomment; that is, a comment on the unfolding conversation.

Vance?s turn is also a representation of something other than speech, using

as BJB did earlier the cartoon ?thinks? bubble.

Example

12e is the main floor of the multiple floor. The previous examples (12a to

12d) can be considered side floors, or even mere asides, in the multiple floor.

|

8 |

LianA

asks, "what does burn the scandle from the two ends mean? who can

help?" |

|

|

|

|

10 |

BJB

[to Lian]: "how long do you think a candle will last if you burn

both ends?" |

|

11 |

LianA

says, "nol not candle but scandle" |

|

12 |

LianA

says, "no---typo" |

|

|

|

|

14 |

PhilB

says, "Lian, it's a play on words." |

|

|

|

|

16 |

LianA

says, "it said if you burn the scandle from 2 ends, you will be

a busy man." |

|

|

|

|

18 |

VanceS

says, "Also you will burn yourself out" |

|

|

|

|

20 |

PhilB

says, "Normally to "burn the candle on both ends" means

to work so much you tire yourself out. With "scandal" instead

of "candle" it sounds like Bill Clinton with his hot interns.

<g>" |

|

21 |

BJB

chuckles. Same result, though. |

|

|

|

|

23 |

VanceS

says, "he must have had too many hot interns in the fire" |

|

24 |

LianA

giggles |

Example 12e

This is a collaborative floor in that four participants are involved in its development. The contention is that it dominates because the verbal activity is explaining about a phrase LianA has read, which involves the communicative action explaining. The topic, raised quite explicitly by LianA in turn 8, is a phrase that LianA has presumably read or heard and that she wants help in understanding what it means. As noted above, LianA is an English language learner, and Webheads is a virtual community dedicated to language learning. In other words, when a language learner raises a language learning point, much of the focus redirects towards that particular floor, the floor becomes collaborative, and the communicative action of the verbal activity orients towards ?explaining?.

In

example 12f the floor type can also be attributed directly to the participant

and the verbal activity:

|

25 |

PhilB

asks, "Hey, I found a new free resource called "stuffincommon

virtual communities". Anyone heard of it?" |

|

26 |

VanceS

says, "never" |

|

27 |

Sue

[guest] says, "no" |

|

28 |

LianA

says, "no" |

|

29 |

PhilB

asks, "Wanna see?" |

|

30 |

VanceS

says, "sure" |

|

31 |

Sue

[guest] says, "sure" |

|

32 |

PhilB

says, "It has chat, tools, and a neat whiteboard." |

|

33 |

LianA

says, "yes." |

|

34 |

PhilB

asks, "I'm going to project. Sue, Lian, do you know about projections?" |

|

35 |

LianA

says, "yes" |

|

36 |

Sue

[guest] says, "not sure" |

Example 12f

This

is a single floor with one floor holder being supported by other participants.

In the terminology adopted here, from Hayashi (1991) and Cherny (1999), it

is a speaker-and-supporter floor. The communicative action of the verbal activity

is primarily didactic: PhilB is demonstrating an internet resource called

?stuffincommon?. There is a sub-topic in turns 34 to 36: using the project

command in Tapped In. The communicative activity remains explanatory.

In

this section the concern has been with a limited set of patterns of participation

and floor types. There are undoubtedly many other patterns which relate to

the development of other floor types. This notwithstanding, the conclusion

can be drawn from this analysis that floor development is related to verbal

activity. When the topic of the verbal activity is a language point raised

by a learner, the floor becomes collaborative. It either develops as the single

collaboratively constructed floor or as the main floor of a multiple conversational

floor. When the topic is related to the technologies of electronic literacy

(for example, how to build a website; or where a particular resource can be

found), the floor develops into a speaker-and-supporter floor. The participant

role is also important. In each case the communicative action (explaining/demonstrating)

is pedagogic. However, when the verbal activity is directly related to the

acquisition of the second or foreign language (English), a number of participants

contribute substantive turns. When the verbal activity is related to the development

of the skills of electronic literacy, other participants focus their attention

on the single floor holder.

6.

Conclusion

Conversation in SCMC is quite different in many ways from spoken conversation. It follows that established approaches to spoken discourse analysis do not necessarily map directly on to a novel form of discourse. For example, as shown in this paper, patterns of turn-taking in SCMC are affected by disrupted turn adjacency, itself a characteristic of the discourse setting ? the virtual environment. Hence certain axioms concerning turn taking in spoken discourse do not apply to conversation in the computer-mediated discourse setting. In this paper it has been maintained that the notion of the conversational floor is a useful one in the study of discourse where cohesion is looser than in the spoken mode. Furthermore, a claim has been made that the development of certain floor types is associated with (a) the roles of the participants in the discourse; (b) the topic of the discourse; (c) the current communicative action or, generally speaking, the purpose of the discourse.

The conclusions can be broadened by engaging with the notion of communicative competence (Hymes, 1972; Canale and Swain, 1980). Effective participation in a particular SCMC environment requires a measure of electronic communicative competence. The elements of electronic communicative competence, as they apply to the context and discourse features described above and adapted from the model of Canale and Swain, include the following:

A knowledge of the linguistic system. The Webheads virtual community includes both learners and expert users of English. However, only a minimum level of English is needed to communicate effectively in SCMC discourse; perhaps less than is needed for similar communication in the spoken mode. The speed of turn-taking is slower than in spoken discourse; participants can scroll back up the screen to re-read parts of the conversation, and logs of the text can be saved and studied at a later time. There are thus arguments for the use of SCMC in language teaching.

A knowledge of the discourse patterns involved. The view of cohesion posited here suggests that it operates through the organisation of various types of conversational floor. For participants, managing these floors and perhaps partaking in different floors in parallel, requires new skills. Regardless of one?s level of competence in the language of the virtual environment, the ability to manage threads of SCMC discourse is a primary skill.

A knowledge of the technology. This knowledge encompasses both access to the technology (the computer hardware and an internet connection) but also a technical knowledge enabling a participant to download particular software, to log on to the system, and to join a virtual community amongst other things.

A knowledge of the sociocultural rules of a particular virtual community. Not all SCMC settings are the same. The final aspect of electronic communicative competence includes a knowledge of the roles of participants, the topic range expected in the context, and the broad purposes of communication in the context.

This paper has only touched on these matters by looking at discourse patterns in one particular SCMC context. There is undoubtedly much scope for the investigation of other areas of floor development in SCMC, and more generally, applying any findings to a nascent theory of electronic communicative competence.

7.

References and URLs

Brown, G. and Yule, G. (1983). Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [cited]

Bublitz, W. and Lenk, U. (1999). Disturbed coherence: ?Fill me in?. In Bublitz et al. (eds.). [cited]

Bublitz, W., Lenk, U. and Ventola, E. (eds.). (1999). Coherence in Spoken and Written Discourse. Selected Papers from the International Workshop on Coherence, Augsburg, 24-27 April 1997. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Canale, M. and Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing? Applied Linguistics 1/1, 1-47. [cited]

Cherny, L. (1999). Conversation and Community: Chat in a Virtual World. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Chun,

D. M. (1994). Using computer networking to facilitate the acquisition of

interactive competence. System, 22/1, 17-31.

Coghlan, M and Stevens, V. (2000). An online learning community: The students? perspective. Paper submitted for the 5th Annual Teaching in the Community Colleges Online Conference, 12-14 April 2000. <http://www.chariot.net.au/~michaelc/TCC2000.htm> [cited]

Cook, G. (1989). Discourse. Oxford: OUP. [cited]

Edelsky, C. (1981). Who?s got the floor? Language in Society 10/3, 383-421. [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Erikson, F. and J. Shultz. (1977). When is a context?: Some issues and methods in the analysis of social competence. Quarterly Newsletter of the Institute for Comparative Human Development 1/2, 5-10. [cited]

Gumperz, J. J. (1977). Sociocultural knowledge in conversational inference. In M. Savile-Troike (ed.) Linguistics and Anthropology: Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1977. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. [cited] [cited]

Halliday, M. A. K. and Hasan, R. (1976) Cohesion in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [cited]

Hayashi, R. (1991). Floor structure of English and Japanese conversation. Journal of Pragmatics 16, 1-30. [cited] [cited]

Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity. [cited]

Herring, S. (forthcoming). Who?s got the floor in computer-mediated conversation? Edelsky?s gender patterns revisited? In S. Herring (ed.) Computer-Mediated Conversation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Herring, S. (1999). Interactional coherence in CMC. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 4/4. <http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol4/issue 4/herring.html> [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Herring, S. and Nix, C. (1997). Is serious chat an oxymoron? Academic vs. social uses of internet relay chat. Paper presented at the American Association of Applied Linguistics, Orlando, FL, March 11 1997. [cited]

Hobbs, J. (1990). Topic drift. In B. Dorval (ed.) Conversational Organization and its development. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. [cited]

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride and J. Holmes (eds.) Sociolinguistics. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [cited]

Jefferson, G. (1984). On stepwise transition from talk about a trouble to inappropriately next-positioned matters. In J. M. Atkinson and J. Heritage (eds.) Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [cited]

Jones, R. H. (2002). The problem of context in computer mediated communication. Paper presented at the Georgetown Roundtable on Language and Linguistics, March 7-9 2002. [cited]

Kern, R. (1995). Restructuring classroom interaction with networked computers: Effects on quantity and characteristics of language production. The Modern Language Journal 79/iv, 457-476. [cited]

Kitade,

K. (2000). L2 learners? discourse and SLA theories in CMC: Collaborative

interaction in internet chat. Computer Assisted Language Learning

13/2, 143-166.

Malinowski, B. ([1923] 1999). The problem of meaning in primitive languages. In C. Ogden and I. A. Richards (eds.) The Meaning of Meaning. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul. Reprinted in A. Jaworski and N. Coupland (eds.) (1999) The Discourse Reader. London: Routledge. [cited]

Murray, D. E. (1988). Computer-mediated communication: Implications for ESP. English for Specific Purposes 7, 1988: 3-18. [cited]

Nofsinger, R. E. (1991). Everyday Conversation. Newbury Park: Sage. [cited]

Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G. and Svartvik, J. (1985). A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.

Rampton, M. B. H. (1990). Displacing the ?native speaker?: expertise, affiliation, and inheritance. ELT Journal 44/2, 97-101. [cited]

Rintel, E. S., Mulholland, J. and Pittam, J. (2001). First things first: Internet relay chat openings. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 6/3. <http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol6/issue 3/rintel.html> [cited]

Salmon, G. (2000). E-Moderating. London: Kogan Page. [cited]

Schegloff,

E. A. ([1968] 1972). Sequencing in conversational openings. American

Anthropologist 10/6, 1075-1095. Reprinted in J. J. Gumperz and D. Hymes (eds.)

Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication. New York:

Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Schegloff, E. A. and Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings.? Semiotica 8/4, 289-327. [cited] [cited]

Seidlhofer, B. and Widdowson, H. (1999). Coherence in summary: The contexts of appropriate discourse. In W. Bublitz et al. (eds.). [cited]

Shultz, J. J., Florio, S. and Erikson, F. (1982). Where?s the floor? Aspects of the cultural organisation of social relationships in communication at home and in school? In P. Gilmore and A. A. Glatthorn (eds.) Children In and Out of School: Ethnography and Education. Washington DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Smith, M. A. and Kollock, P. (eds.). (1999). Communities in Cyberspace. London: Routledge. [cited]

Steele, J. (2002). Herding Cats: A Descriptive Case Study Of a Virtual Language Learning Community. Ph.D. Thesis, Indiana University of Pennsylvania. [cited]

Stenstrom,

A.-B. (1994). An Introduction

to Spoken Interaction. Harlow: Longman.

Stevens, V. (1999). Writing for Webheads: An online writing course utilizing synchronous chat and student web pages. Paper presented at The 4th Annual Teaching in the Community Colleges Online Conference, 7-9 April 1999. <http://www.homestead.com/vstevens/files/efi/hawaii99.html> [cited]

Stevens, V. (2000a). Writing for Webheads: Our methodology. <http://www.homestead.com/vstevens/files/efi/methods.htm>

Stevens, V. (2000b). Developing a Community in Online Language Learning. Proceedings of the Military Language Institute's Teacher-to-Teacher Conference 2000 "Tools of the Trade", May 3-4 2000, Abu Dhabi, UAE. <http://www.geocities.com/vance_stevens//papers/webheads/t2t2000.htm>

Stevens, V. (2001). Implementing Expectations: The Firewall in the Mind. Plenary address delivered at Implementing Call in EFL: Living up to Expectations Conference, University of Cyprus, Nicosia, May 5th - 6th, 2001. <http://www.geocities.com/vance_stevens//papers/cyprus2001/plenary/index.html>

Stevens, V. and Altun, A. (2001). ?The Webheads community of language learners online.? Proceeds of the Military Language Institute?s Teacher-to-Teacher Conference 2001, November 7 2001, Abu Dhabi, UAE. <http://sites.hsprofessional.com/vstevens/files/efi/papers/t2t2001/proceeds.htm> [cited]

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. London: Wiedenfeld and Nicolson. [cited] [cited]

Warschauer,

M. (1996). Comparing face-to-face and electronic discussion in the second

language classroom. CALICO Journal 13/2, 7-26. <http://www.gse.uci.edu/markw/comparing.html>

Warschauer, M. (1999). Electronic Literacies: Language, Culture and Power in Online Education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Werry, C. (1996). Linguistic and interactional features of internet relay chat. In S. Herring (ed.): Computer Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Social and Cross-cultural Perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [cited]

Footnotes and websites

[1] The Webheads home page <http://www.homestead.com/vstevens/files/efi/webheads.htm>

[2] The Webheads email list <http://www.homestead.com/>

[3] Tapped In <http://www.tappedin.org>

[4] The Palace <http://www.thepalace.com>

[5] ICQ <http://web.icq.com>