Abstract: This article explores Thematic variation and its relation to self-presentation in the texts of Ph.D. students' personal homepages. Results show that what is realized as Theme often refers to the Ph.D. students and their dissertation work. That they choose to present themselves or their professional activity as a starting point suggests that Ph.D. students use personal homepages to construct a professional self. A detailed analysis of the marked Themes reveals that the majority of them are circumstantial adjuncts or adverbials of time which function as deictic expressions used to build up a background setting, creating a time-line that lends coherence to the texts. These texts can be identified as narrative life-stories with a past, present and future, and they function as a resource for the homepage authors for creating and maintaining identity and self-presentation on the World Wide Web.

Keywords: Keywords: personal homepages, self-presentation, Theme, World Wide Web, identity, narrative

Multimedia:

The personal homepage is an interesting and intriguing phenomenon. It has evolved quickly and combines many elements, which is why the personal homepage is considered to be the first uniquely digital genre (Dillon and Gushrowski (2000)). Yet, even though the personal homepage meets many of the criteria of a genre, most of us still do not know exactly how to define this new and emergent genre. Both the content and the form of personal homepages are still rather optional which still causes the personal homepage to be very much under development.

Setting up a personal homepage has become increasingly popular and more and more people decide to create their own space in cyberspace. Thus the popularity of the World Wide Web has created a need for more research to understand how communication through the web works and to learn more about its interactive capabilities.

Today there are numerous specialists who advise anyone interested in web-design on how to design an "outstanding website". Other specialists provide technical information needed for creating websites. According to Herring (2003) [1] these specialists take on a prescriptive role which in itself is useful but not adequate enough to explain how web communication takes place. We need to analyse the content of the Web closely and critically in order to broaden our understanding of the personal homepage and at the same time move beyond prescriptivism. This can be achieved through Content Analysis methods, which have already been used extensively to analyse media communication. Lately these methods have been applied to the World Wide Web (e.g. Bates and Lu, (1997), Karlsson (2002)) to identify patterns of structure and meaning in multimedia discourse and images.

Content Analysis is an umbrella term for a range of related methodologies including discourse analysis, rhetorical analysis, semiotics, iconography and link analysis among others. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses are carried out to discover the meaning expressed through text (and through images) to increase our understanding of the communication via the Web.

Most research of the Web conducted through Content Analysis has focused on images and the layout of various web pages. There is almost no literature that analyses the written text of Web pages, which is why detailed textual analyses of the discourse used in homepages are needed to provide a more comprehensive view of how web users communicate via the homepage. This is the main concern of this article.

The focus of the present article is on the Theme in the texts found in personal homepages created by Ph.D. students. The system of Theme belongs to the textual metafunction of language and is concerned with the organization of information within individual clauses, and also with the organization of texts (Martin, Matthiessen and Painter (1997, p.21)). Halliday (1994, p.36) defines the Theme as the point of departure of the message of the clause: it is that with which the clause is concerned. By analysing the choice of constituent in Theme position, one can understand the perspective from which the information in the text is presented. Thus the function of the homepage text is reflected in the Theme choices.

To begin with, I briefly describe the CMC (computer-mediated communication) medium and the personal homepage. I then introduce the Theme according to Halliday's SFG-model (Systemic Functional Grammar) and its relation to texture in the homepage texts which are my data for this paper. Finally, I analyse and discuss the status of the Theme in my data and its function in the homepage texts in relation to narratives and identity (or self-presentation).

CMC or computer-mediated communication is "communication that takes place between human beings via the instrumentality of computers" (Herring (1996, p.1)). Computer-mediated communication varies depending on which technologies it is based on, and also on its contexts of use (Herring (2002)). There are two technologically-determined types of text-based CMC - 'synchronous' CMC and 'asynchronous' CMC - in which participants interact by using the written word. The former type of CMC is communication that takes place in real time (e.g. chat), whereas the latter type is communication where the coding time and the receiving time need not overlap (e.g. e-mail). Homepages belong to the asynchronous type of communication since the reader and the writer are not logged on at the same time and therefore cannot enter into a dynamic and simultaneous interaction with each other. Even if they were logged on at the same time, they could not interact synchronously, because of the time effort required to produce/modify a web page. Moreover, interaction over the Web is asymmetrical, with homepage authors and readers playing non-reciprocal communicative roles. At the same time, homepages are not simply a form of mass communication, in that readers have the option to respond by sending e-mail to the authors, or by signing the page's 'guest book' (Bates and Lu (1997)). The homepage is therefore a rather unusual form of computer-mediated communication as is the rest of the Web, in that it is "semi-interactive one-to-the-World communication" (Miller (1998, p.1)).

Although the Web and homepages are popular ways of communicating, they have not been studied extensively as interpersonal communication media. According to Wakeford (2000), one reason for this is that web-based communication is less interactive than for example chat, e-mail or discussion groups/lists. Therefore some researchers do not consider web-based communication to be a mode of CMC. Furthermore, when an author or a reader of a web page designs or reads the page, they are engaged in 'asymmetrical activities', in the sense that they interact with a machine. However, we could argue that the designers of the pages interact with readers since they want to mediate web pages with content and with meaning. Each page consists of messages conveyed in various ways. It is then up to readers whether they want to give or leave any feedback as a completion of a dialogical communication (cf. by writing in the guest book on personal homepages).

An important issue has been raised by Soukup (2000), who states that researchers lack methods for analysing meaning and structure which are often conveyed through non-textual means within web-based communication. Homepage communication includes many non-textual elements such as links, images, photos, lay-out, colours and frames which need to be analysed to get an overall view of the communicative nature of this particular CMC mode (cf. Karlsson (2002), Kress and van Leeuwen (1996), Snyder (1998)). The textual elements of personal homepages have also gone largely unanalysed. In this study, the focus is on the actual textual elements of the homepage texts, using well-established methods for analysing texts.

"All homepages reveal identity, whether or not that is the intention of their authors" (Walker (2000, p.99)). This statement leads to the question: how do people communicate identity via the personal homepage? One answer would be that the overall design (the impression the homepage sends out) and the lay-out (e.g. the colours and the various fonts used) offer possible ways of presenting the identity of the homepage author (Chandler (1998)). This is of course true to a certain extent, but the information content of a homepage also needs to be carefully considered to determine the messages the homepage author communicates through the written word.

Cheung (2000, p.45) argues that, "regardless of their content, and the motivation behind their production, all personal homepages inevitably involve self-presentation". However, the degree to which people choose to reveal themselves and take social risks varies (Bates and Lu (1997)), since creating a homepage is entirely voluntary. Creating a homepage can both reveal and hide the person behind it. The author of the homepage has the power of deciding just how much or little he or she wants to reveal of themselves. As Steven Rubio (1996, p.1) describes it: "When you visit my homepage, you don't get to know me, but only my presentation of myself". One of the ways in which it is possible to measure the degree of self-presentation in homepages is through Content Analysis of the provided information.

Dillon and Gushrowski (2000) found that the core elements a good homepage cannot do without were: e-mail links, external links, welcome message, 1-4 graphics, brief biography. Bates and Lu (1997) found that the ten most popular items (in descending order) in a personal homepage were: e-mail address, name, favourite websites, gender, photo, current work, educational background, hobbies or interests, mailing address, and previous work experience. They also found that the main purpose of a personal homepage was to present professional capability and experience. Dominick (1999) also carried out a Content Analysis of his data and found that of the content variables, feedback mechanisms (e.g. e-mail address, a visitor counter, a guest book etc.) ranked at the top of a scoring list closely followed by links to other sites. Photographs were also a common feature of most pages. On the whole, however, "it appears that relatively little personal information is contained in personal pages" (p.651), and Dominick thus concludes that the information on the homepages was not very effective in letting the reader get to know the author of the page. Cheung (2000, p.45), however, argues that even though these types of features of the personal homepage give little information of the author, the language, design and content of a homepage still provide indirect evidence for what the author may be like.

The information in a homepage is highly related to the purpose of the homepage. Consequently, personal homepages can be divided into sub-types based on the information content and the purpose of the homepage. The work of Bates and Lu shows that nearly 45% of their data were homepages with the purpose of presenting the author's professional capability and experience and close to 29% were homepages categorized as "play with system capabilities", which were homepages that appeared to have been created mainly for the fun of it [3]. Walker (2000) classifies her data of personal homepages into two main categories, extrinsic pages and intrinsic pages, based on the reasons people gave for creating them. The authors of the extrinsic pages used their pages to sustain interaction with people they already knew, whereas the intrinsic pages were created to establish contact with users of the Internet. Döring (2002) also uses the dichotomy of extrinsic (extrinsically motivated homepages) versus intrinsic pages (intrinsically motivated homepages) in her neat taxonomy of homepage categorisation. She labels personal homepages in which the author makes his/her own person the topic expressive homepages which are further classified as either extrinsic or intrinsic depending on their purpose. Döring finds that only 42% of her data are expressive homepages expressing self-presentation. The rest of the homepages fall into other categories not relevant for identity construction and self-presentation as is the case with the expressive pages.

The above studies are important Content Analysis studies of both the information in the homepages and the purpose of the homepages, which have contributed to our understanding of this new phenomenon. However, the way in which language is used in homepages is one of the most disclosing characteristics of a personal homepage (Chandler (1998)). This is why textual analyses of the homepage discourse need to be undertaken to get an overall and more complete view of this new genre.

Ivanic (1998, p.40) discusses the discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. She argues that social identity has three dimensions corresponding directly to Halliday's three metafunctions, the ideational, interpersonal and textual metafunctions [4]. Ivanic further suggests that all people have a set of values, knowledge and beliefs and that these will affect the ideational meaning which is expressed through language. Furthermore, all people have a sense of their status in relation to other people with whom they are communicating, which will affect the interpersonal meaning of language. Finally, social identity also consists of a person's orientation towards language use and this will affect the construction of the message. If we choose to look at the macrostructures of language in this way, it could be argued that the identities of the discourse participants are constructed through language. Writing is then not only about form and content but also about the representation of self, which makes writing an act of identity and therefore highly interesting to analyse in homepage texts.

In this study Halliday's SFG-model is used to analyse the Theme in each individual clause (both independent and dependent clauses, see section 5.1 below). According to the Systemic Functional Grammar model, language is said to fulfil three overarching functions: the ideational metafunction, the interpersonal metafunction and the textual metafunction. In this paper only the textual metafunction is dealt with, which is the use we make of language to form texts (spoken or written). The clause can also, however, be contextualized in terms of all three of its metafunctional perspectives. The Theme can thus have textual, interpersonal, and ideational stages [5] (Martin, Matthiessen and Painter (1997, p.22)).

The data consist of 24 personal homepages of American Ph.D. students in the humanities (mainly linguistics). The homepages were selected to investigate how students in academia are using homepage discourse.

The homepages have been collected principally by using various search engines on the Internet, for example www.yahoo.com or www.google.com. Universities were also located and from there it was possible to search for Ph.D. students' personal homepages. It is important to emphasize that the official presentations (i.e. template presentations) of the Ph.D. students, which are quite common at most universities, were not of interest here since these presentations are often written in a certain standardized style. Therefore, only the personal homepages which were written by the students themselves and linked to the university sites were collected and focused on.

Following Döring's (2002) classification of homepages, the data of this study fall into the category of expressive, intrinsically motivated homepages since the Ph.D. students are making their own person the topic of their homepages [6].

Instances of continuous texts on the pages, were collected. Homepages which did not consist of any continuous text were excluded (e.g. pages with only lists of information). The continous texts are mainly found on either the index page, which is the very first page of the whole homepage, or on the page following the index page depending on the design of the homepage. The texts vary in length from a few sentences up to about twenty sentences or more, all connected to form a unified whole on the homepage.

Below are two screenshots (Figure 1 and 2) of one of the homepages to illustrate an example from the data. The screenshots are followed by Table 1 which describes the typical homepage features found in the whole sample, i.e. the 24 homepages.

Figure 1: Index-page of Betsy Barry(http://www.arches.uga.edu/~bbarry/)

Figure 2: Betsy Barry's 'About Me' page(http://www.arches.uga.edu/~bbarry/)

| Type of Personal Information Present | N | % |

| Name | 24 | 100% |

| 24 | 100% | |

| CV | 20 | 83% |

| Photos | 17 | 71% |

| Address | 17 | 71% |

| Hobbies, interests | 16 | 67% |

| Conference presentations* | 14 | 58% |

| Publication list* | 13 | 54% |

| Courses taught* | 13 | 54% |

| Phone number | 6 | 25% |

| Fax number | 3 | 13% |

| Weblog | 3 | 13% |

Table 1: Type of personal information present (*These features are sometimes a part of the CV)

Table 1 shows that the five most popular items in the homepage sample for this study are, in descending order, name, e-mail, CV, photos, address [7].

According to Halliday & Hasan (1976, p.1), the word 'text' is used in linguistics to refer to "any passage, spoken or written, of whatever length, that does form a unified whole". Furthermore, a text is a semantic unit, which means that it is a unit of meaning as well as a unit of form. What distinguishes a text from a non-text is that it has texture. The texture of a text is created by the cohesive relations that exist between various linguistic units in the text. The one specific kind of meaning relation that is exceptionally defining for texture is the way one linguistic element is interpreted in relation to or by reference to another linguistic unit.

Structure is one of the most important means for expressing texture. Grammatical units such as clauses and sentences are 'cohesive' in the sense that they are all structured mainly to provide the reader with resources to create 'coherence' of the text. This paper studies the Theme as a central linguistic unit in the homepage texts. By investigating what gets to be the Theme, we can discover how Thematic choices contribute to the cohesion and coherence of a text (Eggins (1994, p.300)). Since coherence is in the minds of the writer and reader (Thompson (1996, p.147)) an analysis of text will increase our comprehension of how the linguistic system enables writers and readers to produce and process coherent meaning. Thus this study is concerned more broadly with what resources of the English language are used for creating texture in personal homepages.

Both Halliday (1994) and Fairclough (1992) view the clause as the main unit of grammar, which can be combined to make up complex sentences and texts. Each clause is seen as multifunctional, having a combination of textual, ideational, and interpersonal (i.e. identity and relational) meanings. All discourse participants make choices (consciously or unconsciously) when they construct their clauses (e.g. about structure and content); they also make choices of how to construct social identities, social relationships, knowledge and beliefs. Through the SFG-framework (cf. Halliday (1994), Eggins (1994), Thompson (1996)) it is possible to provide a clear view of how language users structure their clauses and texts which leads to a better understanding of how identity is built up or constructed in various types of discourses, like for example homepage discourse.

The textual metafunction covers language used as an instrument of communication with which we build up cohesive and coherent sequences. Each clause carries a message, and so the textual aspect can be seen as fulfilling a message function of clauses and is therefore very closely connected to their information structure. In Hallidayan grammar there is an interrelationship between two systems of analysis which both affect the structure of the clause: Information structure and Thematic structure. The former system involves constituents that are labelled Given and New, and the latter system involves constituents that are labelled Theme and Rheme. The two systems are in some ways rather similar in structure and in many clauses the Theme is equivalent to Given information (cf. Prince (1981)), and the Rheme is considered equivalent to New information. Following Halliday (1994, p.299), who treats Given/New and Theme/Rheme as separate approaches, the focus of the current study is on the system of Theme and Rheme.

A common interpretation of Theme is to say that it is "the idea represented by the constituent at the starting point of the clause" (Bloor & Bloor (1995, p.72)). According to Halliday (1994, p.37) the Theme is viewed to be "the point of departure of the message" where each clause is said to carry a message. Another way of expressing the Theme is to say that it is what the clause is about. This explanation however might be misleading since in some cases it might be difficult to distinguish Theme from subject. Therefore the explanation of the Theme as being the starting point of the clause or for the message, is to be preferred (Thompson (1996, p.119)).

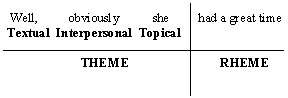

The identification of the Theme is then based on word order. The element which comes first in the clause is the Theme and what comes after it is the Rheme. According to Halliday the Theme analysis involves two layers of analysis: the Theme/Rheme analysis, and within the Theme the level of topical, textual, or interpersonal analysis (a multiple Theme analysis). Clauses which have only one Thematic constituent are said to have simple Themes, and clauses which have more than one constituent are said to have a multiple Thematic structure (Bloor & Bloor (1995, p.77)). Each clause in a text has a Theme which relates to the ideational function of language and is labelled the topical Theme of the clause. In clauses which have simple Themes, with only one Theme identified, the Theme is the topical Theme. However, some clauses can also be assigned a textual and an interpersonal Theme. The textual Theme almost always is the first part of the Theme and fulfils a linking function. It is therefore usually realized by structural conjunctions, relatives, conjunctives, or continuatives. The interpersonal Theme usually follows the textual Theme and typically includes one or more of the following elements: a Finite (an auxiliary verb), a Wh-element, a Vocative, or an Adjunct (typically an adverb). The interpersonal Theme mainly conveys the writer's attitude towards, comment on or assessment of the message of the clause. The ideational or topical Theme is the element of the clause that expresses some kind of representational meaning. Technically, it is a function from the transitivity structure of the clause which implies that it can be either a participant, a circumstance (i.e. giving information about time, place, manner, cause etc.), or a process. In this study, following Halliday (1994, p.53), the Theme comprises all elements up to and including the topical Theme which is then also the boundary between the Theme and the Rheme, as in the following example:

Example 1:

It is important to remember that every clause must contain one and only one topical Theme. Once the topical Theme has been identified, all the clause constituents to the right can be consigned to the Rheme role.

A focus on the Theme element reveals which linguistic elements the Ph.D. students place as starting points of their clauses. Their conscious or unconscious choices of Themes reflect the message of their clauses and hence the intended communicative purpose of their homepage texts. Furthermore, analysing the choices of topical Themes causes the homepage authors' strategy with the texts to crystallize even further, since the patterns of the topical choices in a text provide a possible interpretation of the Mode8 of a text. That is an analysis of the topical Themes gives an indication of the roles they are playing in the homepage interaction between the writer and the reader of the texts. In an academic or scholarly text, for example, "the Mode demands the Thematization of abstractions: we do not depart from our own experience, but from our considered generalizations about people, situations, causes" (Eggins (1994, p.302)). Whereas in a face-to-face conversation we depart from our own experiences. Our point of departure is ourselves. The Modes of a scholarly text and a face-to-face conversation are different and consequently the choices of topical Themes.

The system of Theme is concerned with the organization of information within individual clauses (Martin et al. (1997, p.21)), mainly since the clause is generally considered to be the pivotal unit of grammatical meaning (Eggins (1994, p.139)). Consider Example 2:

Example 2:

If you have any questions, I would be happy to discuss them with you.

In this example the sentence is built up of two clauses, the first dependent and the second independent. If we analyse Theme at clause level there are two Themes ('If you' and 'I'), which are both italicized in the example. However, if we wish to analyse the Theme at the sentence level, the whole if-clause serves as the Theme, which has been underlined in the example. In this study, the analyses are restricted to Themes at clause level rather than analysis of Theme at sentence level.

The texts contained a total of 465 clauses (both independent and dependent). All clauses were treated equally and each clause was analysed for Theme according to Halliday's model (1994, p.37ff) to investigate what linguistic elements are typically chosen as Theme. Table 2 below presents an overview of the types of linguistic elements that are given Thematic status.

| Types of Theme | N | % |

| Mainly pronouns (Unmarked Themes which serve as subject) (Independent clauses: 247=88% , Dependent clauses: 33=12%) | 280 | 60% |

| Circumstantial, modal, textual adjuncts (Marked Themes which serve as adjunct) (Independent clauses: 98=71% , Dependent clauses: 41=29%) | 139 | 30% |

| Verbs (All independent clauses) | 22 | 5% |

| Wh-elements (Independent clauses: 11= 92% , Dependent clauses: 1= 8 %) | 12 | 3% |

| Elements used for politeness purposes (All independent clauses) | 12 | 3% |

| Total | 465 | 101% |

Table 2: Types of Theme

As is shown in Table 2 most of the Themes are either pronouns or various types of adjuncts. Furthermore, Themes represented by verbs, Wh-elements and elements used for politeness purposes [9] present a smaller proportion. To clarify the analysis further, example 1 above would have been categorised as an unmarked Theme since the topical Theme is a pronoun and serves as subject in the example.

Since mood [10] is part of the Thematic structure of a clause, the choice of Theme in a clause is related to the choice of mood. Clauses with a subject as Theme is the typical pattern for a declarative clause and are said to have unmarked Themes [11]. Declarative clauses with Themes other than a subject are said to have marked Themes. Adjuncts (adverbial groups, prepositional phrases) and Complements (nominal groups, nominalizations) are typical marked Themes. Clauses which have a verb (the predicator) as Theme are regularly labelled imperative clauses and can function as either unmarked or marked Themes (Halliday (1994, p.47)). Wh-elements which are given Thematic status are found in interrogative clauses where the Theme is constituted only by the Wh-element. Themes in interrogative clauses are mainly unmarked but occasionally marked Themes do occur (Halliday (1994, p.47)). In Table 3 the distribution of the unmarked and marked Themes in declarative clauses are shown.

| Declaratives | N | % |

| Unmarked (Independent clauses: 247=88% , Dependent clauses: 33=12%) | 280 | 60% |

| Marked (Independent clauses: 98=71% , Dependent clauses: 41=29%) | 139 | 30% |

| Total | 419 | 90%* |

Table 3: Unmarked and marked Themes in declarative clauses (* For the remaining percentage, see the discussion below)

Examples of unmarked and marked Themes from the data are shown in italics and in Examples 3 and 4:

Example 3:

I am a Ph.D. candidate in the Linguistics department … (unmarked)

Example 4:

As is illustrated in Table 3, the unmarked Themes are much more frequent with 60% of all clauses than the marked Themes with 30% of all clauses. This result indicates that the remaining part of the clauses, 10% of all clauses, have Themes which categorize the clauses as something other than declaratives.In Fall 2001 - Fall 2002, I will be teaching introductory courses in…(marked)

Table 4 presents an overview of the various types of clauses found in the data.

| Types of clauses | N | % |

| Declaratives (Independent clauses: 345= 82% , Dependent clauses: 74= 18 %) | 419 | 90% |

| Interrogatives (Independent clauses: 11= 92% , Dependent clauses: 1= 8 %) | 12 | 3% |

| Imperatives (Independent clauses: 22= 100%) | 22 | 5% |

| Minor clauses (Independent clauses: 12= 100%) | 12 | 3% |

| Total | 465 | 101% |

Table 4: Distribution of types of clauses

The analysis shows that most clauses, 93%, are in the indicative mood. Declaratives is the largest group with 90% of all clauses and interrogatives represents 3% of all clauses. Twenty-two clauses are in the imperative mood which represents 5% of all clauses. I have added and labelled the final category, minor clauses (cf. Martin, Matthiessen and Painter (1997, p.71)), which are said to fulfil a minor speech functional meaning. According to Halliday (1994, p.43), minor clauses do not have Thematic structure and are usually left out of account when clauses are analysed for Themes. However, in my data minor clauses are typically politeness elements used to maintain harmonious relations in the discourse and can thus be seen to serve an interpersonal function in the dialogue between the writer and the reader. Minor clauses are therefore important linguistic features, which need to be taken into consideration to increase our understanding of the nature of the interaction going on between the writer and the reader of homepage discourse. Examples 5 and 6 below are some examples of minor clauses taken from the data, where the politeness element has been written in italics:

Example 5:

Thanks for stopping by…

Example 6:

Welcome to my homepage.

In the following sections the Themes in the various types of clauses will be discussed in relation to the homepage discourse. First there is a section discussing the unmarked and the marked Themes in declarative clauses followed by a section where the Themes in interrogative, imperative, and minor clauses are discussed.

As shown in Table 3 the Themes consisting of the subject make up the largest group of the declarative clauses with 60% compared to the marked Themes with 30%. The majority of the unmarked Themes consist of pronouns. Most frequent is the personal pronoun I in initial position followed by the possessive pronoun my. Other pronouns like you and we are also represented but not to the same extent [12]. Table 5 below presents the frequency of the pronouns found in the data.

| Types of Pronouns | N | % |

| I | 232 | 79% |

| my | 44 | 15% |

| you | 13 | 4% |

| we | 5 | 2% |

| Total | 294 | 101% |

Table 5: Frequency of pronouns

One possible explanation for using the same clause initial element may be that the writers make use of thematic repetition, e.g. the personal pronoun I, to create topical coherence, i.e., the topic of the homepage as a whole is I. The repetition of the same subject becomes a way for the writers to structure their text coherently.

Brown and Yule (1983, p.183) point out that it is reasonable to assume that the constituent which is thematised in a sentence is "what the sentence is about". And since the majority of the homepage writers have placed the personal pronoun I as the Theme, it underlines that their texts are about themselves, as is illustrated in examples

Example 7:

I am a 4th year doctoral student in the linguistics program…

Example 8:

I have a pretty vast research agenda that includes…

Example 9:

I have spent a good deal of time researching various…

Furthermore, Brown and Yule (1983, p.134ff) discuss the notion of Theme and 'topic entity' and suggest that Theme (following Halliday) refers to the left-most constituent of a clause while topic entity refers to Theme as meaning main character. In Examples 7 and 8 the main character is the writer him-/herself and so the writer's topic entity is the first person pronoun I. From an interactional point of view, the initiating pronoun I indicates that the writer assigns himself the role of informer in the discourse, informing the reader about him-/herself.

When the writers place the pronoun you as the Theme, they are always directing the readers of the homepage, which shows that there is an active interaction going on, a dialogue, between the writer and the reader through the homepage discourse. Examples 10 to 14 illustrate the use of the pronoun you in the data. The Theme is italicized and the pronoun is underlined.

Example 10:

You can send me e-mail at …

Example 11:

You may be interested in my resume.

Example 12:

If you have any questions about myself, my research, or…

Example 13:

..., or if you have comments or suggestions about this webpage…

Example 14:

..., or if you prefer a more Metropolitan approach …

The pronoun we also appears as Theme, as in Examples 15 and 16:

Example 15:

We have a web page, which is put together by…

Example 16:

We are up to about 120 gigs of data…

Here the writers are using we when they are mentioning various projects that they are working on together with other academics. As for the use of the possessive pronoun my it is always connected to the writers' academic ideas, research, interests, papers, dissertation, address or department, as in Examples 17 to 21, where the whole Theme is in italics and the pronoun is underlined.

Example 17:

My idea is to…

Example 18:

My research focuses on…

Example 19:

My research interests include…

Example 20:

My Qualifying Paper for PhD Candidacy examined…

Example 21:

My campus mailing address: …

In seven examples does the subject in Theme position refer to the homepage itself as in Examples 22 to 24:

Example 22:

This site includes…

Example 23:

This page was last updated…

Example 24:

This is the personal web page of …

These Themes are metalinguistic and they may be said to function as spatial deictic expressions. The examples above suggest that the writer puts his/her own homepage in relation to other homepages in the vast cyberspace. One's own personal homepage is emphasized in relation to other sites, showing an awareness of the homepage as a new phenomenon in a larger context - the Internet.

The marked Themes are the Themes not conflated with the subject. It is interesting to see what kind of elements are chosen as clause initial elements besides the subject. As shown in Table 1, 30% of all Themes are adjuncts. There are three types of adjuncts, all with different functions. These are circumstantial adjuncts (prepositional phrases, adverbs of time, manner, place etc.) which add experiential content to the clause by expressing some circumstance relating to the process represented in the clause; modal adjuncts (mood, comment, vocative adjuncts) which add interpersonal meanings to the clause by creating and maintaining the dialogue between writer and reader; and textual adjuncts (conjunctive and continuity adjuncts) which add textual meaning to the clause to organize the message itself. Table 6 presents the distribution of the various types of adjuncts that were found in Theme position.

| Textual Adjunct | Modal Adjunct | Circumstantial Adjunct | Total | |

| N | 16 | 17 | 72 | 105 |

| % | 15% | 16% | 69% | 100% |

Table 6: Distribution of adjuncts in Theme position

Table 6 shows that the circumstantial adjuncts are the most frequently used adjuncts in Theme position, followed by modal adjuncts and textual adjuncts. Below follow examples of the various types of adjuncts. Some of the Themes are multiple Themes and some of them are simple marked topical Themes (fronted circumstantial adjuncts). Therefore, the whole Theme is in italics and the specific adjunct exemplified is underlined.

There were 16 instances of a textual adjunct in the data. In Example 25 the textual Theme is underlined and provides a linking relation to the previous clause. Examples 26 to 29 are first and foremost fronted circumstantial adjuncts and have ideational meaning: temporal in Examples 27 and 29, and manner in Example 26. However, they all have a text organising function in the homepage discourse and can therefore be viewed as textual. Furthermore, Example 28 also functions as a metalinguistic Theme, referring to the homepage itself.

Example 25:

In addition to Creoles, I am also interested in…

Example 26:

That way I get to combine my affinity for…

Example 27:

Eventually, we hope to make all…

Example 28:

And last but not least, I am currently…

Example 29:

After that I scooted off to Brussels…

The modal adjuncts represent 16 % of the adjuncts in Theme position and they add interpersonal meanings to the clause, i.e. they add meaning which is connected to the construction and the maintenance of the dialogue between the writer and the reader of the homepage. There are clauses which start with modal adjuncts (underlined in the examples) which convey the writers' judgement of the relevance or truth value of their messages (Halliday (1994, p.49)). Examples are:

Example 30:

Perhaps, it was the early exposure…

Example 31:

There are also other types of modal adjuncts (see Eggins (1994, p.166)). In Example 32 a comment adjunct (Halliday (1994, p.83)) is presented, which adds expression of the writer's attitude and evaluation. Example 33 is a focusing adjunct, expressing the writer's specific focus.Hopefully, my learning pursuits will make…

Example 32:

Broadly, the goal is to find out …

Example 33:

Particularly, I am interested in …

The majority of the adjuncts, 69%, are circumstantial adjuncts, which add meanings which refer to time (rather than to space, cause or matter), as in Examples 34 to 38:

Example 34:

During the summer following my graduation, I worked as a…

Example 35:

The following September I entered…

Example 36:

In April 2000 I completed…

Example 37:

Currently, I am …

Example 38:

At present I am in large part funded by…

The above examples are like Examples 26 to 29, i.e. simple marked topical Themes or fronted circumstantial adjuncts, which add ideational meaning to the clause. However, it is important to point out that Examples 34 to 38 also have textual meaning since they contribute to the organization of the discourse.

In the analysed texts, the circumstantial elements have a very important role in that they create the background of the message of the clause. Usually, the writers want to give an account of their academic career and therefore go back in time to talk about past achievements. Then they move on to discuss their current academic situation, and finally finish by telling the reader about their academic plans for the future. The Theme is developed on the basis of the authors' achievements so far.

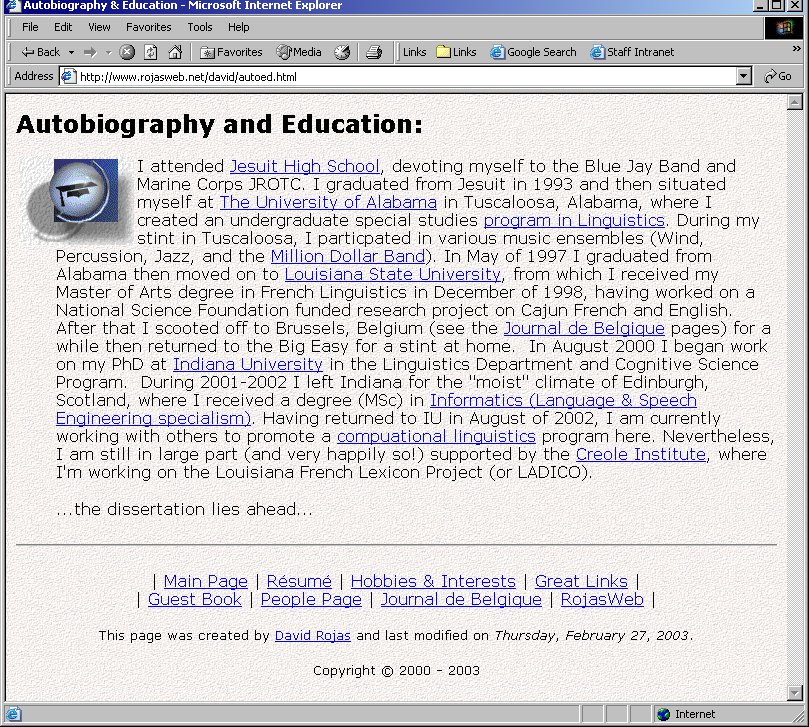

Figure 3 below is a screenshot of one personal homepage to illustrate the use of circumstantial adjuncts.

Figure 3: Illustrates the autobiography and education page of David Rojas.(http://www.rojasweb.net/david/autoed.html)

To present the text in the homepage more clearly it has been copied and the circumstantial adjuncts are marked in bold in Example 39:

Example 39:

Homepage of David Rojas, Linguistics, Indiana University, http://www.rojasweb.net/david/

I attended Jesuit High School, devoting myself to the Blue Jay Band and Marine Corps JROTC. I graduated from Jesuit in 1993 and then situated myself at The University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, where I created an undergraduate special studies program in Linguistics. During my stint in Tuscaloosa, I particpated in various music ensembles (Wind, Percussion, Jazz, and the Million Dollar Band). In May of 1997 I graduated from Alabama then moved on to Louisiana State University, from which I received my Master of Arts degree in French Linguistics in December of 1998, having worked on a National Science Foundation funded research project on Cajun French and English. After that I scooted off to Brussels, Belgium (see the Journal de Belgique pages) for a while then returned to the Big Easy for a stint at home. In August 2000 I began work on my PhD at Indiana University in the Linguistics Department and Cognitive Science Program. At present I am in large part funded by the Creole Institute, where I'm working on the Louisiana Lexicon Project (or LADICO)--link to come after I get the public site up and running.

The readers of the homepage, however, will not be able to make sense of the deictic expressions in Theme position unless the writer refers to time that can be deictically interpreted in relation to the reader's experience of time. Deictic expressions such as currently and at present can thus be ambiguous and writers must anticipate the effects of the time lag between the production of the clause and the reception (cf. Levinson's coding time and receiving time, Levinson (1983, p.73)). However, due to the asynchronous nature of the medium, homepage writers usually do not update their personal homepages by the minute. Consequently, placing adjuncts of time in Theme position of a clause restricts the actual statement or message of that clause with regards to time. This problem is sometimes solved by the writer of the homepage by stating the date [13] when the page was last updated, which helps the reader to interpret the deictic expressions in the texts. In this way the date when the page was last updated becomes the deictic centre for the reader. The deictic centre from where the deictic expressions should be interpreted originates from the writer not the reader. Hence, the deictic centre becomes of great importance for the reader's understanding and experience of the coherence of the homepage text.

In addition to declarative clauses, Table 4 above also shows that the data consist of other types of clauses. This section investigates interrogative clauses, imperative clauses and minor clauses.

The characteristic function of an interrogative clause is to ask a question (Halliday (1994, p.45)). When a question is asked, an answer or response is usually required. This is the basic pattern of an interaction between speaker/hearer and in this study between writer/reader. In the data, 3% of the clauses are interrogative clauses which have Themes composed of question words, or Wh-items such as Where, Why, When, How (Martin et al. (1997, p.30)) which solely constitutes the Theme in the clause. In English the writer or speaker does not actually choose to place the Wh-element in Thematic position, it is part of the system of the language. It is in the very nature of a question in English to have the Wh-item in initial position of the clause (Halliday (1994, p.46)).

The interrogative Wh-elements can add both interpersonal and topical meanings to the clause (Halliday (1994, p.54), Table 3(7)). However, to illustrate the degree of interaction going on in the homepage discourse I will merely consider the interpersonal meanings that the Wh- elements add to the clause. Examples of Wh-elements (Themes) from the data are in italics in the following examples:

Example 40:

Why bother?

Example 41:

What is an American anyways?

Example 42:

Who am I?

Example 43:

What are they?

Example 44:

Where would you like to go now?

In the above examples, the writer is asking questions which are directed to the reader of the homepage. At the same time, however, in stating these questions the writer is not really expecting the reader(s) to contact him/her and provide an answer to the questions, hence the interrogatives in the above examples can be viewed as rhetorical. Yet, this interpretation does not minimize the value of the interactive contribution of the interrogatives to the homepage discourse. The questions demonstrate that there is a degree of involvement of the writer in the reader of the discourse.

As shown in Table 4, the imperative clauses constitute 5% of the clauses in the data and can be divided into two main groups based on the function of their Themes in the discourse. There are imperatives with Themes adding meaning of politeness to the clause and there are Themes adding meaning of physical action to the clause.

The basic function of imperative clauses is either 'I want you to do something' or 'I want us (you and me) to do something'(Halliday (1994, p.47)), and this function is indicated by the Predicator (or the verb) which is given Thematic status in the clause. The majority of the imperatives in the data encourage the reader(s) to perform a physical action of some sort connected to the design and the structure of the homepage. Examples of Themes where the writer requests the reader(s) to carry out an action are illustrated in Examples 45 to 47 below (the Themes are in italics).

Example 45:

Click here for our web page.

Example 46:

Click here for my CV.

Example 47:

Browse the menu to your left for more information.

The examples above also have a metalinguistic character since the writer is giving the reader(s) instructions of how to surf the homepage itself, to get the information wanted.

The other group of imperatives are clauses where the Theme mediates a sense of politeness directed towards the reader. According to Thomas (1995, p.157f) politeness strategies are used to achieve certain goals. Consider the following examples:

Example 48:

Please feel free to check out some of my work.

Example 49:

Please enjoy some of the images I've put up of some of my work.

The goal in this context is for the writer to create a polite and harmonious relation with the reader through the discourse by using polite imperatives ('feel free', 'enjoy') intensified by the initial use of the politeness marker 'please'.

The final clause category shown in Table 4 is that of minor clauses, which represents 3 % of the clauses in the data. Following Martin et al. (1997, p.71) and Halliday (1994, p.95f), minor clauses are said to have a semantic role in dialogue and hence serve an interpersonal function. In the homepage data these types of clauses are to a large extent greetings and exclamations. Consider the following examples:

Example 50:

Hello!

Example 51:

Hello, everyone.

Example 52:

Hello, my name is…

Example 53:

Welcome to the homepage of…

Example 54:

Welcome to my webpage.

Example 55:

Thanks for visiting my website.

In the above examples there is clear evidence of the writer's concern for creating and maintaining a polite and friendly atmosphere in the discourse. These minor clauses can be compared to greeting clauses used in traditional writing, e.g. letter writing. In traditional letter writing we would not find clauses like those in Examples 53 to 54 which are commonly used in this new medium. This is much due to the fact that on the Internet a reader can actually visit different places, one of which may be a personal homepage. The result is that the writer must adapt the text to the context and therefore finds it necessary to invite the reader(s) to the personal homepage, almost the same way as when inviting someone to a home (hence term 'homepage' [14]).

Structure is one important means for expressing texture. In the homepage texts, texture is created by means of adverbials of time in the Theme slot. The clauses which start with an adverbial of time, taken together, create a time-line throughout the text to give the readers an insight into the past, present and future events of the authors' lives. The authors can thus be said to give a narrative account of their personal experiences. Labov (1997) discusses the concept of narratives of personal experience. He defines this type of narrative as "a report of a sequence of events that have entered into the biography of the speaker/writer by a sequence of clauses that correspond to the order of the original events" (p. 2). In my data the homepage authors use narrative to create one particularly important part of their own lives - the academic part.

The concept of personal narrative is further discussed by Linde (1993) who introduces the notion of life story. She defines the life story as an oral linguistic unit that is part of social interaction. However, the notion of a life story can fruitfully be used in the context of homepage texts since a written text, too, can be regarded as a form of social interaction. According to Linde, all people have life stories which are stories that express our sense of self. A life story is related to our internal sense of having a life story that organizes our understanding of our past life, current situation and imagined future. They reveal who we are and how we got that way. Furthermore, "…we use these stories to claim or negotiate group membership and to demonstrate that we are in fact worthy members of those groups, understanding and properly following their moral standards" (p. 3). This is particularly interesting in connection to the current data which are homepages constructed by a particular group of people in society - doctoral students who are still novices, striving to establish themselves as acknowledged academic professionals.

This study suggests that narrative is used as a resource for creating and maintaining personal identity in homepage discourse, and that such narrative is structured in significant part through choice of clause Theme. The data shows that the doctoral students are creating their academic identity by giving an account of their academic career pointing out their skills and academic achievements. The Themes, both the unmarked and the marked, support their accounts. The frequency of the pronoun I indicates that the messages, the meanings of the clauses, and the topic entity of the writers are the doctoral students. The adverbials of time in Theme position show that the past, present and future are of importance since they set the context for the rest of the message of the texts. The adverbials thus create texture and form a time-line through the texts that creates coherence for the readers of the homepage.

Furthermore, this study also shows that there are two main types of Themes in the homepage texts. Following Berry's (1995, p.55-84) division of Themes into 'informational' Themes and 'interactional' Themes, Themes that are concerned with the students' doctoral research and the temporal sequence of their careers along with Themes which function as the writer's topic entity (e.g. the initial pronoun I) are categorized as informational Themes, providing the reader(s) with information that has been given prominence in the homepage texts. However, the initial pronoun I may also be interpreted as interactional Theme, since the writer takes on the role of the informer, telling the reader about his/her academic life. Further interactional Themes are the Themes found in the interrogative, imperative and minor clauses. Themes in all these clauses show a high degree of writer involvement in the reader. The writer welcomes the reader to his/her own little home in cyberspace and at the same time tries to create a harmonious and pleasant stay for the visitor. The reader is guided within the homepage while surfing the site through the writer's use of interactional Themes.

Most studies on personal homepages and self-presentation (cf. Cheung (2000), Dominick (1999), Miller (1998) point to the same thing: the personal homepage is a communicative device used by people to express themselves in various ways. Through detailed textual analyses this study has shed some light on how texts in personal homepages are used by people to tell the world who they are.

Bates, M.J. & Lu, S. (1997). An exploratory profile of personal homepages: Content, design, metaphors. Online and CDROM Review 21 (6), pp. 331-340. http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/H ome_pages-n_970614.html [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Berry, M. (1995). Thematic options and success in writing. In M. Ghadessy (ed.), Thematic development in English texts (pp. 55- 84). London. [cited]

Bloor, T. & Bloor, M. (1995). The functional analysis of English: A Hallidayan approach. London: Arnold. [cited] [cited]

Brown, G. & Yule, G. (1983). Discourse analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [cited] [cited]

Chandler, D. (1998). Personal homepages and the construction of identities on the Web. http://www.aber.ac.uk/~dgc/webident.html. [cited] [cited]

Cheung, C. (2000). A home on the Web: Presentations of self on personal homepages. In D. Gauntlett (ed.), Web studies: Rewiring media studies for the digital age (pp. 43-51).London: Edward Arnold. [cited] [cited] [cited]

Crystal, D. (1997). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics. Oxford: Blackwell. [cited]

Dillon, A. Gushrowski, B. (2000). Genres and the web: Is the personal homepage the first uniquely digital genre? http://www.slis.indiana.edu/adillon/genre.hml [cited] [cited]

Dominick, J.R. (1999). Who do you think you are? Personal homepages and self-presentation on the world wide web. J & MC Quarterly 76(4): 646-658. [cited] [cited]

Döring, N. (2002). Personal home pages on the Web: A review of research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 7(3). http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol7/issue3/doering.html [cited] [cited] [cited]

Eggins, S. (1994). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. London: Pinter. [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Fairclough, N.(1992). Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press. [cited]

Halliday, M.A.K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar, 2nd edition. London: Edward Arnold. [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Halliday, M.A.K. & Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. London: Longman. [cited]

Herring, S. C. (ed.) (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Linguistic, social and cross-cultural perspectives.Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [cited]

Herring, S. C. (2002). Computer-mediated communication on the internet. In Cronin , B. (ed.). Annual review of information science and technology [cited]

Ivanic, R. (1998). Writing an identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Studies in written language and literacy 5. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [cited]

Karlsson, A-M. (2002). Skriftbruk i förändring: En semiotisk studie av den personliga hemsidan. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. [cited] [cited]

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge. [cited]

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (1998). Front pages: (The critical) analysis of newspaper layout. In A. Bell & P. Garett (eds.), Approaches to media discourse (pp. 186-219). Oxford: Blackwell.

Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city. Oxford: Blackwell.

Labov, W. (1997). Some further steps in narrative analysis. http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~wlabov/sfs.html [cited]

Levinson, S. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [cited]

Linde, C. (1993). Life stories. The creation of coherence. New York: Oxford University Press. [cited]

Martin, J.R., Matthiessen, C.M.I.M & Painter, C. (1997). Working with functional grammar. London: Arnold. [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited] [cited]

Miller, H. (1998). The presentation of self in WWW homepages. http://www.ntu.ac.uk/soc/psych/miller/millmat.htm [cited] [cited]

Prince, E. (1981). Toward a taxonomy of Given-New information. In P. Cole (ed.), Radical pragmatics, pp. 223-297. New York: Academic Press. [cited]

Rubio, S. (1996). ‘Home Page’, Bad Subjects 24. http://english-www.hss.cmu.edu/bs/24/rubio.html [cited]

Snyder, I. (ed.) (1998). Page to screen. London: Routledge. [cited]

Soukup, C. (2000). Building a theory of multi-media CMC. New Media & Society 2: 407-425. [cited]

Thomas, J. (1995). Meaning in interaction: An introduction to pragmatics. London & New York: Longman. [cited]

Thompson, G. (1996). Introducing functional grammar. London: Edward Arnold [cited] [cited] [cited]

Wakeford, N. (2000). New media, new methodologies: Studying the Web. In D. Gauntlett (ed.), Web studies: Rewiring media studies for the digital age (pp. 31-41). London: Arnold. [cited]

Walker, K. (2000). “It’s difficult to hide it”: The presentation of Self on Internet homepages. Qualitative Sociology, vol. 23:1. Human Sciences Press. [cited] [cited]

[1] Course syllabus, "Content Analysis for the World Wide Web", taught by Susan Herring during Spring 2003, at SLIS, Indiana University, Bloomington. See http://ella.slis.indiana.edu/~herring/web.syll.03.html [cited]

[2] Döring (2002, p.7) theoretically distinguishes 'identity' and 'self' by stating that identity is the more narrow concept, while self is the broader concept. [cited]

[3] For the remaining percentage, see http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/Home_pages-n_970614.html [cited]

[4] The textual metafunction covers language used as an instrument of communication with which we build up cohesive and coherent sequences. The interpersonal metafunction describes the use we make of language as an interpersonal medium. In the ideational (or experiential) metafunction the clause is used to represent the experiential world (i.e. real world phenomena).

[5] These stages are demonstrated in Example 1 in this study. [cited]

[6] See section 6.3.1 and the discussion in section 8. [cited]

[7] Bates and Lu (1997) found in their study that the ten most popular items of personal homepages were e-mail address, name, favourite websites, gender, photo, current work, educational background, hobbies or interests, mailing address, and previous work experience. [cited]

[8] The role language is playing in the interaction (Eggins (1994, p.52))

[9] See the discussion of minor clauses below Table 3. [cited]

[10] The principal grammatical system of the interpersonal metafunction is MOOD, whereby the clause functions as an exchange between ourselves and others. The three broad types of MOOD are: indicative (declaratives, interrogatives), imperative and subjunctive. [cited]

[11] The general definition of markedness is that the unmarked form represents the most neutral and expected form, whereas the marked form represents the unexpected form (Crystal 1997:233). [cited]

[12] For a previous analysis of pronouns in CMC see e.g., Yates, 1996 in Herring ed. [cited]

[13]The date is sometimes also added by the program that is used for making the homepage. Bates and Lu (1997) found this feature in 43% of the personal homepages they analysed. [cited]

[14] Bates and Lu (1997) found that only a minority of personal homepages in their study explicitly invoked the 'home as domicile' metaphor. [cited]