Abstract: The so called ‘net generation’ is popularly assumed to be naturally media literate and to be necessarily reinventing conventional linguistic and communicative practices. With this in mind, this paper reports the analyses of qualitative data arising from a investigation of 159 older teenagers’ use of mobile telephone text-messaging - or SMS (i.e. short-messaging services). In particular, I examine the linguistic forms and communicative functions in a corpus of 544 of participants’ actual text-messages. While young people are surely using their mobile phones as a novel, creative means of enhancing and supporting intimate relationships and existing social networks, widespread claims about the linguistic exclusivity and impenetrability of this particular technologically-mediated discourse appear greatly exaggerated.

Keywords: text-messaging, young people, linguistic forms, communicative functions,computer-mediated discourse, language change

Multimedia: A tables and figures are presented in PDF format

Nearly a billion text messages whizz around the UK every month. Whenever and however you like to send you text messages, it’s a completely individual way to express yourself. (Orange Magazine, Spring 2001)

Mobile phone ownership is universal, and people use them constantly. If you don’t have a mobile, you’re effectively a non-person. (www.orange.com).

Figures and claims like these abound regarding the popularity, ubiquity and capacity of mobile phones in general and text-messages in particular (Teather, 2001). It seems that these technologies for communication have become an essential feature of both popular and commercial rhetoric about new media cultures and especially of so called ‘global communications’. Which is not to say that this technology is properly global; worldwide patterns of mobile phone usership necessarily follow the socioeconomic contours of which distinguish the 'media rich' and 'media poor' more generally (Carvin, 2000). Nonetheless, from a more academic perspective, Katz & Aakhus (2002) cite figures estimating the worldwide usership of mobile phones is approaching a billion. (This compares with an estimated 600 million people online <www.nua.com>). Although not true for the USA, where the internet continues to be the communication technology of preference, penetration rates in countries in Western Europe (e.g. Scandinavia, UK, Germany & France) and East Asia (e.g. Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea and Taiwan) are believed to be as high as 70-80%. [note 2]

According to Umberto Eco (2002), we live in an age where the diminutive, the brief and the simple are highly prized in communication; if this is the case, then there’s little doubt that text-messaging embodies this zeitgeist. Like many earlier communication technologies, however, the mobile phone has come to evoke and/or embody a range of projected fears and hopes (Turkle, 1995). In fact, the history of the development of communication technologies is one marked by periods of excessive hype and hysteria about the kinds of cultural, social and psychological impacts each new technology is likely to have. Having said which, few people – professional or lay – could have predicted the extraordinary rise in popularity of the mobile phone in many countries and its sister technology SMS (‘short messaging service’). Initially intended for purely commercial purposes (Bellis, 2002), text-messaging is in fact yet another example of how the human need for social intercourse – a kind of ‘communication imperative’ – bends and ultimately co-opts technology to suit its own ends, regardless of any commercial (e.g. the telephone) or military (e.g. the internet) ambition for the technology.

Typical of media representations about the role of mobile phones in the lives of young people, Bryden-Brown’s (2001) characterization in the The Australian newspaper (heading above) presents yet another image of the media-savvy, technologically-enslaved young person [note 3]. It is not unusual for young people to be caught up in adults’ anxious projections about the future (Griffin, 1993; Davis, 1990); in the case of mobile phones, however, there’s a double-whammy of adult mythology, with the coming together of popular discourses about young people and about new technologies combine. Increasingly, writers are starting to challenge the misleading hype inherent in popular notions like ‘cyberkids’ and the ‘net generation’ (e.g. Thurlow & McKay, 2003 in press; Facer & Furlong, 2001; see also, Holloway & Valentine, 2003). In fact, as Keri Facer & Ruth Furlong (2001) note, there are many children and young people in supposedly technologically advanced countries like Britain who still face a kind of ‘information inequality’ – not only as a result of poor access at home and school, but also because of individual resistance to, and the perceived irrelevance of, computing technology. It is precisely for this reason that homogenizing assumptions about the role of technology in the lives of young people and young adults need constantly to be challenged.

While exaggerations about the significance of personal computing may be questionable, the fact remains that, in many countries, the mobile phone is an altogether far more popular, pervasive communication technology than in others (Katz & Aakhus, 2002). What is more, although by no means any longer the sole province of young people (Cyberatlas, 2001a), in a country like Britain, it is understood that half of all 7-16-year-olds have a mobile phone of their own (NOP, 2001a) and marginally more girls (52%) than boys (44%). In fact, the same NOP survey also shows that as many as 77% of 14-16-year-olds have mobile phones. Richard Ling (2002) also reports recent figures from Norway, another mobile-saturated country, which specifically identify young adults/older teenagers as the heaviest users. Unquestionably, a core feature of almost all young people’s mobile phone use is the text-message, with most sending upwards of three text-messages a day.

Central to the hype and hysteria of popular, media representations about new communication technologies are concerns about the way that conventional linguistic and communicative practices are affected. A fairly typical example of this is the comment quoted in the heading above made by John Humpreys (2000), a British radio journalist notorious for his ‘verbal hygienist’ (Cameron, 1995) concerns about, amongst other things, the putative ‘death’ of the apostrophe in English. Much popular attention is given nowadays to the perceived communicative paucity of young people (Thurlow, 2001a) and both ‘teen-talk’ and ‘netlingo’ (or ‘webspeak’) are often blamed for supposedly negative impacts on standard or ‘traditional’ ways of communicating. The same is especially true of young people’s use of mobile phones and text-messaging, where they are often understood to be – or rather accused of – reinventing the (English) language (for a recent example, see Henry, 2002)[note 4]. In this sense, therefore, added to populist concerns about young people and new technologies are common folklinguistic concerns about threats to standard varieties and conventional communication practicesmore generally – that young people and new technologies might be to blame merely compounds matters.

With reference to other communication technologies – most notably the internet and web – scholars of computer-mediated communication (CMC) have for some time been challenging the assumption that technologically-mediated modes of communication are necessarily impoverished and antisocial (Walther & Parks, 2002; Spears et al., 2001). Not least because so much CMC is text-based, more specific interest has also been with emerging linguistic forms and practices – or computer-mediated discourse (CMD) (Herring, 2001, 1996; Baron, 1998; Werry, 1996; Collott & Belmore, 1996). One of the principle arguments of both CMC and CMD is that generalizations about communicative and linguistic practice are inherently problematic, conflating as they do important differences in the affordances and constraints of different technologies such as email, online chat, instant messaging, newsgroups and bulletin boards, webpages and ‘virtual worlds’. Spcifically, as Herring (2001) also notes, language will necessarily be affected by technological (or medium) variables such as synchronicity (e.g. where instant messaging is synchronous, email is asynchronous), granularity (i.e. how long or short text may be) and multimodality (e.g. whether or not graphics, audio and video are included), as well as other non-linguistic variables such as participants’ relationships, expectations and levels of motivation.

Apart from being unambitious, talking about text is yet another way of focusing on young people. …grown-ups often seek to legitimate their own conversation by orienting it around youth … putting their own spin on the youthful activity of text messaging – but what of the activity itself? (Calcutt, 2001)

Distinguishing between 'expert framing' and 'folk framing' respectively, Katz & Aakhus (2002) have recently commented on how little academic input there has been to balance everyday, popular discourses about mobile phones. While the Information Society Research Centre at the University of Tampere in Finland (e.g. Kasesniemi & Rautiainen, 2002) has been researching the mobile communication culture of children and young people since 1997, this is seldom the case elsewhere. What is more, for all the hype and hysteria about text-messaging and young people’s use of text-messaging in particular, I know of no research which has specifically examined the linguistic practices of text-messaging in the way that, say, Naomi Baron (1998) has done with email messages or Christopher Werry has done with online chat. Nor is there an extensive mobile phone survey to compare with the Pew Internet & American Life Project's (2000) report on the use of the internet and instant messaging (IM) among young American people – the CMC technology which competes most directly with text-messaging for the attention of young people in the USA.

It was because of this noticeable hiatus that I was keen to undertake the following ‘snapshot’ survey as a means of tracking the use of ever new communication technologies by young people, and as a way of rendering more empirical populist claims about the language text-messaging. The study also offers a different, British perspective. With both Baron (1998) and the Pew Report (2000) as useful backdrops, the current study was therefore framed by two straight-forward research questions relating to the linguistic forms and communicative functions of young people’s text-messaging: (a) what are young people using text-messaging for? and (b) to what extent are they experimenting with conventional language in their text-messages? It is answers to questions such as these which help to improve the sociolinguistic mapping of new technologies (cf. Thurlow, 2001b).

Using as a convenience sample, a first-year Language and Communication class I teach at Cardiff university was asked towards the end of one lecture to retrieve from their phones five messages that they had either sent or received in the previous week and to transcribe them as accurately as possible (i.e. ‘exactly as they appeared on the display screen’). This was done as part of a larger questionnaire study being conducted by Brown (2002) also examining patterns of SMS use (e.g. reasons for using it, people they send messages to, and whether or not they use ‘predictive text’) and other practical considerations such as the amount of money spent on text-messaging, the person who pays the bills, and the network used. Participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses; this was especially important given the personal nature of the messages.

Of the students available, 135 (aproximately 70%) of them responed to this request. The mean age of participants was 19, with three-quarters of them female students (n = 120, 75%) and a quarter of them male students (n = 39, 25%). As is typical of the university’s intake more generally, with 28% of the students actually from Wales itself, almost all the participants were British (98%). While Cardiff University attracts a largely White, generally middle-class population of students, there is no apparent reason why this sample might not otherwise be fairly representative of young, university-age adults in Britain as a whole. However, even though anecdotal evidence suggests that many other young people their age are equally heavy users of mobile phones and text-messaging,I obviously cannot assume that the sample is more widely representative in terms of educational background and socio-economic status.

A total of 544 separate messages were recorded by participants which were transcribed as accurately as possible into a single electronic document. Each message was then analysed in terms of a number of central interests: (a) length (i.e. number of words/characters used); (b) main typographical and linguistic content (e.g. emoticons, abbreviations and letter homophones), and, in line with standard Content Analytic procedures (cf. Bauer, 2000), (c) thematic priority/primary function. At this stage, and partly given the size of the sample, it has not been necessary to undertake elaborate statistical analyses other than to calculate descriptive tendencies in terms of message length.

The length of individual messages was calculated using the standard Microsoft Word ‘word count’ function; this is a crude calculation since it is unable to distinguish lexical items conjoined by a punctuation mark (e.g. i’ll be there later today.what time are u coming?) but does include individual-character lexemes such as the ‘u’ in the same example. On this basis, the average length of text-messages was 14 ‘words’. Compared with the average length of turns in online chat (e.g. 6 words - Werry, 1996), the messages of participants were certainly longer which was to be expected from the kind of asynchronous interpersonal communication afforded by SMS. However, given the standard restriction imposed on the length of text-messages (i.e. usually about 160 characters, including spaces), it was also interesting to note that the average length of participants’ text-messages was only 65 characters (Md = 55, Mo = 13, 23, 39), although with quite a lot of variation (SD = 45). While much is made about the technologically imposed need for brevity in SMS, participants’ messages seldom used the available space; the length (and abbreviated linguistic forms) of messages would therefore seem instead to be a function of the needs for speed, ease of typing and, perhaps, other symbolic concerns. Indeed, as others have noted elsewhere (for Finland: Kasesniemi & Rautiainen, 2002; for Germany: Rössler & Höflich, 2002), young people appear increasingly to be employing SMS for more dialogic exchanges – especially when the costs are lower as is the case in Finland. In this sense, therefore, the language of SMS starts to look much more like the ‘interactive written discourse’ of a conventional CMC niche like IRC (Werry, 1996:48). I return to this point later.

With obvious implications for linguistic practice, it is worth noting that some mobile phones enable ‘predictive text’, meaning that users need only press once on the keypad number corresponding to the letter; as long as the desired word is already stored, the phone should recognize and complete it automatically. When asked earlier in the questionnaire by Brown (2002), however, only about half (55%) of participants reported using this facility – mainly because it was thought to be quicker and easier. On the other hand, reasons given by those 37% who said they didn’t use predictive text included, in order of priority, that it was too difficult to use, they did not actually have the facility to start with, it was annoying, it did not choose the right words, it was slower to use and did not facilitate the need for abbreviations.

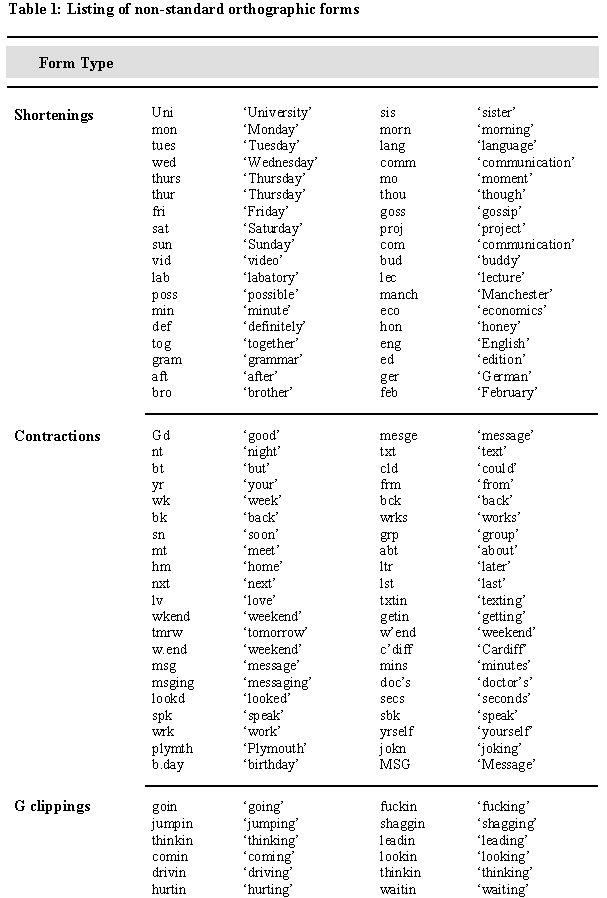

Following the kind of typology offered by Tim Shortis (2001), in Table 1 (Pdf version for download) is listed every different example found in participants’ transcribed messages of what might reasonably be regarded as a non-standard orthographic and/or typographic forms, organising them into the following broad categories: (1) shortenings, contractions and G-clippings and other clippings, (2) acronyms and initialisms, (3) letter/number homophones, (4) ‘misspellings’ and typos, (5) non-conventional spellings, and (6) accent stylizations. [note 5]

Heavily abbreviated language is of course also a generic feature of interactive CMC niches like IRC’s online chat and ICQ’s instant messaging and I was not surprised to see that, in Section 1 of the questionnaire, 82% of participants reported using abbreviations in their text-messages, especially the women (F = 89%; M = 57%). However, in looking at their actual text-messages, only 1401 examples of abbreviations were found – about three per message – which meant that abbreviations in fact accounted for less than 20% (18.75%) of message content. As I discuss shortly, this finding runs counter to popular ideas about the unintelligible, highly abbreviated ‘code’ of young people’s text-messaging.

In the same vein, only 509 typographic (as opposed to alphabetic) symbols were found throughout the entire corpus – the vast majority of which were simply kisses and exclamation marks usually in multiple sets (e.g. xxxxxx and !!!!!). There were also only 39 instances of emoticons (e.g. :-) ), even though, earlier in the questionnaire by Brown (2002), just over half of the participants actually reported using emoticons, and especially the female participants (F = 56%; M = 38%). (See Table 2 - pdf file) One important limitation of the current study was that the origin of actual text-messages written down by participants was not known – for example, if they were sent or received and who they were sent by. As such, I have been unable to calculate the relative use of a range of different linguistic and typographical forms by males and females, for example. Nevertheless, these figures for the reported use of emoticons would otherwise be consistent with women’s greater use of such (para)linguistic modifiers in comparable (i.e. text-based) computer-mediated discourse (see Witmer & Katzman, 1997).

YO YO YO HESS WOZ UP IN DA HOOD?!HOW IS MAZZAS?WHEN U GOIN BACK?LOVE ME X [M1: Participant 70 / Message 3]

There were also relatively few (n = 73) examples of what are referred to here as ‘language play’, and, like many of the paralinguistic and prosodic cues found in IRC by Werry (1996), instances of language play were most commonly in the form of accent stylizations or phonological approximations such as the ‘regiolectal’ (Androutsoplouos, 2000:521) spelling novern for ‘northern’ and those in [M1] above. In addition there was a range of onomatopoeic, exclamatory spellings (e.g. haha!, arrrgh!,WOOHOO!,t’ra, Tee Hee, Oi oi savaloy!, yeah, yep, yay!, rahh, ahhh, mchwa!, eh?, and woh!) and a couple of other typographical-cum-linguistic devices for adding prosodic impact (e.g. quick quick, wakey wakey, wotcha, and yawn…). Unless used in marked isolation, it was not possible to determine if the use of capitalization such as in [M1] was used deliberately for prosodic effect or if, as I suspected here, it was the sender’s personal style preference to send all their messages in capital letters anyway (see also p.31).

Finally, as one quick reposte to journalist John Humphreys (see above), there were in fact 192 apostrophes used across the 544 messages (e.g. we’re, she’s, can’t, I’m, it’s); this is about one in every three messages (or 35% of them) which otherwise seems surprising given the technological imperative for speed and ease of ‘typing’. Without anything to compare it with, however, it is hard to make any claims for this figure, except to say that, as far as the supposedly solecisitic participants in the current study were concerned, it does not appear that the apostrophe is dead just yet!

Language is always multifunctional and always dependent on context for its meaning. As such, it was not always possible to be certain of the meaning of some participants' messages and even less so the communicative intent with which they were sent. In looking to code their text-messages, however, messages were coded in terms of their primary content-themes; on this basis, individual messages were assigned to nine broad categories. The multifunctionality of the messages was retained to some extent by coding messages in terms of more than one category where relevant (some 121 messages in all, i.e. 22%). In order to render this process of categorization as explicit as possible, examplars for each category are given here, with original messages indicated in a different font and tagged with participant and message numbers according to the transcription protocol. (All messages used in this paper have been numbered in sequence for ease of reference.)

Where's sardinia?Answer me quick hun! xx [M2: Participant 78, Message 1]

Put money in ur account [M3: Participant 99, Message 5]

I Passed [M4: Participant 29, Message 1]

I'm not feeling v well can you get the lecture notes for me please [M5: Participant 31, Message 3]

Where shall i meet you tonite?what time?See u soon love me x [M6: Participant 155, Message 1]

Wanna come to tesco? [M7: Participant 149, Message 5]

R WE DOIN LUNCH THIS WK?CHE [M8: Participant 22, Message 2]

Hello.Me and laura want2go2jive2moro.Does u want us 2 buy tickets [M9: Participant 103, Message 5]

Yo man whats de goss [M10: Participant 39, Message 2]

morning,how are you today?love you xxjtxx [M11: Participant 118, Message 4]

Happy Birthday, i hope you are having a good one,see you in a few days.Love Duncan x x x x [M12: Participant 14, Message 1]

Don't worry bout exam!Just had hair cut & look like a ginger medussa!Arrgh! [M13: Participant 18, Message 4]

R u bak already khevwine?!i am not comin 4 anuva 2 wks,but khevwine, u r the sexiest thing since sliced bread!c & sexia then sliced bread!oh my luv.I miss u so!x [M14: Participant 38, Message 1]

Each time ur name appears on my phone i smile like this :) [M15: Participant 97, Message 2]

Read ur email-thought waz gonna burst so horny xxxxxx [M16: Participant 1, Message 5]

Your wish is my command!I promise to be a better hostage next time.Sweet dreams princess.xxx [M17: Participant 103, Message 4]

I believe friends are like quiet angels who lift our feet when our wings forget how to fly!send to 4 friends and sont send back and see what happens in 4 days [M18: Participant 133, Message 1]

sex is good,sex is fine,doggy style or 69,screwin 4 free or getting paid,everyone loves getting laid,so spread ur legs,lay on ur back,lick ur lips & text me back! [M19: Participant 153, Message 3]

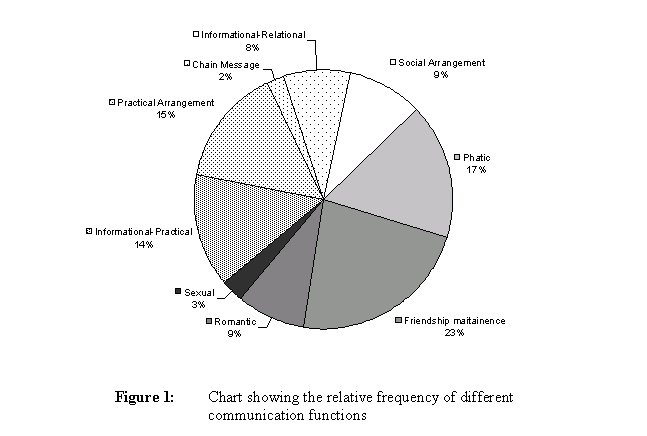

In Figure 1 (Pdf version for download), all the messages are shown distributed in terms of these primary thematic categories. Even though, theoretically speaking, it is impossible to separate ‘doing sociability’ from information exchange (Jaworski, 2000:113), and as Thurlow (2001a) has shown, for analytical convenience it can be revealing to compare the relative weighting of 'relational' and 'informational' dimensions of communication in participant responses. With the 'transactional' or 'interactional' orientation of text-messages tending to be either foregrounded or backgrounded, it was possible to locate each of the principle content themes along a continuum according to the relative degree of intimacy expressed by each as in Figure 2 (Pdf version for download).

On this basis, and relying on the Informational-Relational category as some notional midway point, initial content analyses of participants' 544 messages revealed that at least two thirds of participants' messages were explicitly relational in their orientation, ranging from making social arrangements, phatic communion, friendship maintenance, to romantic, flirtatious and openly sexual exchanges. In fact, recognising the possibility that chain messages too have a relational orientation (see below) and that many of the messages dubbed 'practical arrangements' may well represent a more implicit social arrangement, the amount of explicitly transactional messaging was relatively small – as little as 15% of all the message codings.

In addition to their predominantly relational orientation, other initial impressions of the general tone and content of participants’ messages are noted briefly in the following sections.

Within the general category of friendship maintenance, were found a range of messages of apology, thanks and support (e.g. M12 and M13 above). I have also identified a number of instances where text-messages were being used by friends to stay in touch while apart and also as means of resolving (e.g. M20) – and, possibly, instigating (e.g. M21) conflict:

u stupid girl,why ru upset & worried?i'm not in a mood or stressed so u shouldn't be + def don't b scared of me-i'm a softy!cu in a bit x [M20: Participant 64 / Message 4]

Olly's brought up the house again!Wanker!He's said he reckons you + him'll "come to blows" by the end of the year.He'll fucking die! [M21: Participant 71 / Message 2]

It is these types of messages which most clearly indicate the way in which participants appeared to rely on text-messaging to facilitate relational maintenance and social intercourse, and to complement their face-to-face interactions.

Another strong impression formed throughout my reading of the messages was an overriding jocularity or teasing tone. Although humour is generally very difficult to discern by third parties – not least given that it is intensely context-dependent – there were nonetheless numerous instances where the messager's intent was very clearly humorous.

Simon said you didn't come home last nite.U dirty stop out [M22: Participant 101 / Message 4]

You are a drunken fool with a bad memory [M23: Participant 52 / Message 1]

We believe that this once again helps to fulfil the generally phatic (cf. Malinowski, 1923) function of text-messaging by which an almost steady flow of banter is used in order to maintain an atmosphere of intimacy and perpetual social contact. In this sense, text-messaging is small-talk par excellence – none of which is to say that it is either peripheral or unimportant (see Coupland, 2000).

Beyond their notable sexual content, the chain messages might also be regarded as a form of ‘gifting’ (Ling & Yttri, 2002:159), whereby messagers – especially so amongst younger teenagers – forward these stock sentiments and saucy jokes not only to communicate some desired aspect of identity, but also as means of social bonding through (potentially) shared humour and taboo breaking. As such, although apparently transactional in content, chain messages are clearly more relational in function. Although there were only a handful altogether in the current data-set, what sexual jokes were found were almost always reported by male participants which would not be atypical of the often (hetero-)sexualized nature of young men’s conversational discourse (Edley & Wetherell, 1997; Cameron, 1997).

Allowing also for the sexual tone of many of the chain messages, a striking number of the messages oriented around romantic and, occasionally, sexual themes – either as subject matter (M24 below) or interactional goal (M17 above).

HAD SEX! [M24: Participant 12 / Message 2]

It is in this way, that SMS shows itself to offer an interesting mix of intimacy and distance not unlike various other CMC niches such as IRC, IM and, to an extent, email. The technical rapidity and ephemerality of SMS seem to bring with them a relative anonymity even though, unlike the CMC of much online chat, the sender and receiver are invariably revealed to each other through caller/number display. Nevertheless, it is this kind of ‘recognised anonymity’ which might explain the relative licentiousness or flame-potential of some of the messages reported by participants (see O’Sullivan & Flanagin, 2000, for a discussion these issues in internet CMC). In fact, in the first part of the questionnaire as many as 52% of participants had already reported sending a text-message to say something they wouldn’t ordinarily say face-to-face.

Within the general message category ‘Practical Arrangement’ were an important sub-grouping of messages which exemplify precisely the kind of interpersonal co-ordination discussed by Ling & Yttri (2002) and which they refer to as ‘hyper-coordination’. What is meant by this is the type of mundane, micro-level coordination involved in redirecting trips already started (e.g. 'I need to pick up some milk; can we meet at the store instead?'), letting people know that you're going to be late (e.g. 'I'm held up in traffic but will be there in ten minutes hopefully') or confirming exact timing and location (e.g. 'I'm walking up the high street right now – are you still waiting in front of the post office?'). From the current data-set, examples included:

C u in 5 min x [M25: Participant 11 / Message 5]

LATE [M26: Participant 22 / Message 1]

Where r u?We r by the bar at the back on the left. [M27: Participant 52 / Message 2]

It is this finely-tuned arrangement-making which demonstrates one of the clearest instances of mobile telephony’s shaping a new, distinctive style of social interaction; Ling & Yttri (2002:144) propose that this type of mundane, micro-level organising allows for both the ‘structuring and rationalization of interaction’. Certainly, it would seem from the data that a high premium is placed by young people/adults on such continual accessibility and connectivity – or what Katz & Aakhus (2002) characterise as ‘perpetual contact’ – and that, once again, this is done primarily in the service of social intercourse.

Related to this sense of perpetual contact, and as another example of how text-messagers capitalize on technological affordances (more on this point below), participants had messages revealed contact which was so continual to the extent of being actually co-present:

Who the girls your with is it one of your adoring fans? [M28: Participant 130 / Message 1]

Have you had a shower today as i'm sure I can smell u from here!(Teehee) [M29: Participant 63 / Message 1]

In both these instances, where sender and receiver are apparently within viewing distance of each other, they are able to interact covertly, enabling an immediate, and potentially very intimate, form of communication. The subversive potential in this kind of secret messaging is seen even more clearly in M30, another co-present text-message, where sender and receiver appear to be sitting in the same lecture but are able to contravene interactional norms undetected. [note 6]

How r u sweetie?Why am I doing this subject?It's just so boring!cu soon xxx [M30: Participant 53 / Message 3]

It is this ‘culture of concealed use’ (Ling & Yttri, 2002:164) which again makes apparent how and why text-messaging has come to be stitched so seemlessly into the social fabric of young people’s lives; by no means necessarily replacing face-to-face interaction, mobile phones and SMS enhance communication in ways which allow for multiple (or even parallel) communication events, offering an attractive combination of mobility, discretion, intimacy and, indeed, fun – illicit or otherwise.

txtin iz messin,

mi headn'me englis,

try2rite essays,

they all come out txtis.

gran not plsed w/letters shes getn,

swears i wrote better

b4 comin2uni.

&she's africanHetty Hughes [note 7]

As I suggested at the start, much is said too easily about the uniformity of so called ‘youth culture’, from the tempestuous nature of young people’s relationships, to their dependence on anti-normative practices, and their zealous take-up of new technologies. As Griffin (1993:25) describes it, ‘“youth” is/are continually being represented as different, Other, strange, exotic and transitory – by and for adults.’; nowhere is this more true than the heightened images in the press and broadcast media regarding young people’s use of new technologies generally and mobile phones in particular. Certainly, new communication technologies can empower young people and many do indeed explore and develop imaginative ways of making the technology work best for them (Thurlow & McKay, 2003 in press). Furthermore, as is clear from the current case-study investigation, mobile phones and text-messaging are undoubtedly very popular among older teenagers/young adults. Notwithstanding this, what I have been interested in doing is to address some of the ubiquitous generalizations about young people's use of text-messaging, and, specifically, to examine the reality behind popular notions of their somehow reinventing language in the way that Hetty Hughes’ well-publicized poem implies.

In situating text-messaging in the broader context of computer-mediated (or at least technologically-mediated) communication, much the same need arises for establishing the interplay between what the technology itself allows (or affords) and what the communicator herself/himself brings to the technology. Most obviously, in the case of text-messaging, the equipment is small and, eponymously, mobile; it therefore affords users an unobtrusive and relatively inexpensive mode of communicating. At the same time, text-messaging is also technically restricted to allowing only a certain number of characters per message, and, like text-based CMC, is ‘QWERTY-driven’ (Hale, 1996) – a point I address in the section which follows. Whether or not an aspect of the technology (or ‘medium variable’ – Herring, 2001:614) is a constraint or an opportunity, however, invariably depends on the user. For example, unlike the landline telephone and instant messaging, the asynchronicity of text-messaging affords greater control over when and how messagers respond to incoming messages. Ling & Yttri (2002:159) make the point that this allows users time for reflection before having to respond which in turn allows greater face management. Importantly, however, the degree of synchronicity is more in the hands of its users (unlike email, IRC and the telephone) so that the time between receipt and reply may also be varied. Indeed, as is revealed in the data set for this paper, and as Kasesniemi & Rautiainen (2002) have noted in their long-term research, young people’s text-messaging is becoming increasingly dialogic and, as such, resembles online chat in its conversational structure (i.e. turn-taking and message length).

It is in this way that users infuse an ostensibly asynchronous technology with a certain synchronicity in the way they actually use it; as is so often the case, the technology is thereby co-opted and exploited to serve the underlying imperatives of intimacy and social intercourse. Other seemingly minor affordances of text-messaging also reveal substantial interpersonal benefits: for example, being able to turn the sound off allows for more discrete, parallel exchanges; the forward function (like email) facilitates the gifting’ of chain messages; and, in addition to the face-saving potential of asynchronicity, caller/number display which enables users to screen incoming calls. [note 8]

As Uses & Gratifications Theory (McQuail et al., 1972) proposes, audience-related variables invariably reveal the nature of a technology better than the technology itself – which is to say, it is the needs people seek to gratify which explain how they will actually use a technology. For example, more recent research (e.g. Dimmick et al., 2000) has shown how the principal gratifications of the telephone to be sociability (i.e. social bonding), instrumentality (i.e. social coordination) and reassurance (i.e. security and understanding). Rafaeli (1986 in Rössler & Höflich) also comments on the 'Ludenic' or entertainment qualities technologies.

Ling & Yttri (2002:151) suggest that certain of the affordances are especially attractive to children and teenagers – most notably: (a) being constantly accessible to, and in touch with, friends, and (b) being outside the purview of, and beyond the immediate reach of, parents and other authority figures. Although the second of these appears to play a smaller role with the young adults in the current study, there can be little doubt that accessibility and friendship contact continue to be immensely important. For the young people in this study, it seems that text-messaging can be characterized in terms of at least four gratifications, each of which may be compared with another CMC technology like email: high transportability (more so than email), reasonable affordability (more so than email), good adaptability (e.g. also voice-phone) (perhaps equivalent to email in the light of its increasing multimodality) and general suitability (e.g. it is quiet, discrete). Ultimately, however, the over-riding gratification which each in turn appears to serve is the need for intimacy and social intercourse.

That relationship-building and social intercourse are both central to, and facilitated by, technologies for communication should be in no doubt (cf. Parks & Floyd, 1996; Walther, 1996), even though popular opinion still feeds on the once scholarly idea that computer-mediated communication is necessarily asocial and/or antisocial (see Walther & Parks, 2002, for a discussion of these arguments). Certainly, opinion about the advantages of mobile phones often centres on practical or instrumental benefits such as convenience and security, followed by accessibility and control (see Leung & Wei, 2000). [note 9] Nonetheless, perhaps even more so than the telephone (Hutchby, 2001:80), the mobile phone and text-messaging are ‘technologies of sociability’. As participants’ messages show, much of what is being transmitted to and fro is at the level of phatic communion and/or the kind of micro-level social coordination described by Ling & Yttri (2002). That this is so, was evident not only in the functional or communicative orientation of participants’ messages but was also revealed in the linguistic and orthographic content of their messages.

[Text-]messages often bear more resemblance to code than to standard language. A text filled with code language expressions is not necessarily accessible to an outsider. The unique writing style provides opportunities for creativity. (Kasesniemi & Rautiainen, 2002: 183 – emphasis ours).

Netspeak is a development of millennial significance. A new medium of linguistic communication does not arrive very often, in the history of the race. (Crystal, 2001:238-9)

As has been the case with language on the internet where, for example, the language used by young instant messagers is described as a ‘new hieroglyphics’ (Pew Report, 2000), lay and academic discussions about the language of text-messaging are invariably caught up in an exaggerated sense of its impenetrability and exclusivity – hence references to ‘code’, ‘unique’ and inaccessibility in the Kasesniemi & Rautianen quote above. Just as technologies do not replace each other, nor is it really possible to imagine communicative practices breaking completely, or that dramatically, with long-standing patterns of interaction and language use. For all Crystal's millennial rhetoric about ‘netspeak’, new linguistic practices seldom spring from nowhere, neatly quashing pre-existing forms and conventions; instead, there are always gradual processes of emergence, convergence, divergence and decline.

In her paper on the language and communication of email, Baron (1998) sought to grapple with the idea that email might herald a new linguistic genre; her conclusion was ultimately that it rather represents a creolizing blend of written and spoken discourse. Like email, and indeed most CMD, text-messages have much the same hybrid quality about them – both in terms of the speech-writing blend but also in terms of old and new linguistic varieties. [note 10] Although, as such, I am partly persuaded by Rössler & Hölfich’s (2002) notion of text-messaging as ‘email on the move’, this sort of metaphoric label belies the complex nature of discourse as being always contingent, dynamic and hybrid. [note 11] In its transience and ephemerality, for example, text-messaging is as much like instant messaging as it is like email – and, indeed, speech. In keeping with Herring’s (2001) proposals, therefore, I am more inclined to view the language of SMS in its own terms; whatever formal similarities it may bear with other types of CMD, the linguistic and communicative practices of text-messages emerge from a particular combination of technological affordances, contextual variables and interpersonal priorities.

From what I have seen in participants’ text-messages, and not unlike much CMD, the language of SMS does appears to be driven by three key sociolinguistic ‘maxims’ (cf. Grice, 1975), all serving the principle of sociality which drives the messaging:

(1) brevity and speed;

(2) paralinguistic restitution; and,

(3) phonological approximation.

As the first and indeed foremost of these, the dual maxim of brevity and speed is manifested most commonly in (a) the abbreviation of lexical items and (b) minimal use of capitalization and standard, grammatical punctuation (e.g. commas and spaces between words). Importantly, and as I have already suggested, the need for both brevity and speed appears to be motivated less by technological constraints, but rather by discursive demands such as ease of turn-taking and fluidity of social interaction. Likewise, in terms of the second and third maxims, where paralinguistic restitution understandably seeks to redress the apparent loss of such socio-emotional or prosodic features as stress and intonation, phonological approximation adds to paralinguistic restitution and engenders the kind of playful, informal register appropriate to the relational orientation of text-messaging. On occasions, the second and third maxims appear to override the brevity-speed maxim, but in most cases all principles are served simultaneously and equally. So, for the sake of paralinguistic restitution, capitalization (e.g. FUCK) and multiple punctuation (what???!!!) may be more desirable; on the other hand, lexical items such as ello, goin, and bin serve both the need for abbreviation and phonological approximation. Nevertheless, some graphical punctuation seems more persistent, most notably the use of question marks (?) and full-stops (.). With reduction of ‘typographic contrastivity’ (Crystal, 2001:87), however, the use of capitalization and punctuation becomes more semantically marked and, in this way, grammatical marks are co-opted for other less grammatical effects (e.g. wow!!!! or No wait…). Another example of paralinguistic restitution in graphical form is the famous emoticon – a direct borrowing from netlingo and a feature which appears to be similarly unpopular and, therefore, relatively infrequent – in spite of its exaggerated depiction in the media.

Beyond the most obvious impact on linguistic forms of the sociolinguistic maxims, what has been most noticeable about the non-standard items (or ‘new’ linguistic forms) in the current corpus is how so few of them were especially new or especially incomprehensible (see list in appendix). There were, in fact, few examples of items which were not semantically recoverable, even in isolation of their original, discursive context; much of what participants recorded would not be out of place on a scribbled note left on the fridge door, the dining-room table or next to the telephone – where precisely the same brevity-speed imperative would apply. [note 12] In this sense, therefore, claims (both academic and lay) for the impenetrability and exclusivity of SMS language are clearly exaggerated and belie the subtlety and contextuality of discourse. Like the fridge-door note-maker, SMS users surely recognise the obvious need also for a certain intelligibility – in Gricean terms, for example, quantity and manner (Grice, 1975). One of the best examples of this, in terms of abbreviation, is the use of consonant clusters (e.g. THX), recognising that consonants usually have more semantic detail/value than vowels. Besides, many of the non-conventional spellings found in participants’ messages (see appendix) have a currency which is more widespread and pre-dates SMS; examples of this include the use of z as in girlz, the k in skool, as well as those which also entail phonological approximation such as Americanized (or even AAVE) forms like gonna, bin, coz and any g-clippings like jumpin, havin, etc.

In point of fact, the orthographic (or typographic) conventions and the sociolinguistic maxims which underpin the language of text-messaging evidenced in this corpus are interesting but, in some respects, largely unremarkable. The notion of standardness in written language is itself a convention and always an abstraction from spoken language (see Cameron, 1995) and in this sense, therefore, like the fridge-door note and the phonetic transcriptions of expert linguists, many of the typographic practices of text-messaging offer more ‘correct’, more ‘authentic’ representations of speech.

The use of non-standard orthography is a powerful expressive resource. … [which] can graphically capture some the immediacy, the ‘authenticity’ and ‘flavor’ of the spoken word in all its diversity. … [and] has the potential to challenge linguistic hierarchies… (Jaffe, 2000:498)

In their text-messages, young people write it as if saying it to establish a more informal register which in turn helps to do the kind of small-talk and solidary bonding which is desired. The language they use is therefore not only intelligible but also appropriate to the overall communicative function. What is more, in a message like M31, it is apparent that they also approach SMS language with a metalinguistic awareness and a robust sense of play:

hey babe.T.Drunk.Hate all luv.Have all men.Fuck them.how r u?We’re ou utery drunk.im changing.Now.Ruth.xxx. Hate every1 [M31: Participant 57 / Message 3]

It is a similar metapragmatic awareness which may also account for messagers’ use of such apparently clichéd forms as letter-number homophones and emoticons in the sense that they may be used with ironic effect and/or self-consciously to enact or perform ‘text-messaging’. In other words, in the Hallidayan sense (Halliday, 1969/1997), the act of texting has both an interpersonal and textual function as people send messages not only for the kinds of communicative functions outlined above (e.g. relational bonding and social coordination) but also to be seen to be texting inasmuch as texting and mobile phones also carry cultural capital in and of themselves (cf. Kasesniemi & Rautiainen, 2002; Ling & Yttri, 2002). Put more simply, they are also fashion accessories and ludic resources in their own right. Irrespective of message content, the very act of texting (currently) has cachet and communicates something about the sender; part of buying into the cachet of texting is drawing on discursive-cum-identity resources such as ringtones, keypad covers, and popularized linguistic markers like initialisms, clippings and letter-number homophones.

All of which also raises the question of personal style and register; for example, compare the following messages:

AS IF,wot ugly unsespectin minga has got u?only jokn fatsy,I new ud laf,dats i sent it-erd ur doin levis proj,did u 12 borrow mine? [M32: Participant 73 / Message 3]

Moo!we live at 32 Sudbry Rd which is next to the Dough café past the Firkin – if you want,I could meet you at the Firkin though.xx Bazz [M33: Participant 41 / Message 3]

Hi mate,how are you today?I’m watching Eden on channel 4,and I know the girl called Cliona.This is really weird.Going to the gym later on.Have a nice day [M34: Participant 35 / Message 2]

Probably the most reasonable explanation for the noticeably different orthograhy in Messages M32 and M33 would be the difference in their communicative functions (relational and informational respectively) which prompted an understandable shift in register. However, the difference between two relational messages such as Messages 32 and 34 is less clear and might just as easily index a difference in the personal style of the messagers. In much the same way, assumptions about other discursive patterning in text-messaging (e.g. length, use of capitalization, emoticons and so on) need to be made with caution; for example, in addition to situational and conversational factors, personal preference may just as easily account for the differences in length is M35 and M36, where one exchange runs across two messages (see also my comments on p.10 about length):

What? [M35: Participant 38 / Message 5]

Safe Hi babe!Angie + Lucy had words last nite-stood there arguing 4 ages,loads of people outside cobarna.Bit obvious they……werent gonna fight tho cos they were there 4 so long!I was a bit pissed (woh!) Good nite tho!Spk 2u lata xxBeckyxx [M36: Participant 140 / Messages 1 & 2]

In fact, a colleague (and more experienced text-messager) informs us that it is not uncommon for recipients to recognise the ‘visual signature’ (cf. Jaffe, 2002:509) of incoming messagers based on cues such as abbreviations and emoticons or and message length, in addition presumably to common discursive style markers like topic and lexicon. It is surely a mistake to assume that text-messaging and/or young people are any less sensitive to contextual concerns for register and style, or that there is little variation in the appearance of messages; discursive factors such as interactional function and not technological features are just as likely to account for the relative use of ‘new’ linguistic forms.

The assumption is so often that the language of new technologies for communication is English (Thurlow, 2001b; Yates, 1996), although there is little doubt that the global impact of English and the emergent discourse practices of new technologies are heavily interdependent. For example, Kasesniemi & Rautiainen (2002) note how English is a regular feature of the text-messages of the Finnish children and teenagers they have been studying over the past five years. In the case of this study, however, the use of languages other than English was found only six times – not surprisingly for a predominantly monolingual, English-speaking campus.

Bore da moz.Sri am dihuno ti!Wyt t you dod i darlith medieval Europe am 2?Ost ya, t isie cwrdd tu fas law building am 1:50?Nia xxx [M37: Participant 141 / Message1]

Ello cariad.Caru ti lds [M38: Participant 29 / Message 3]

Bist du ok? [M39: Participant 81 / Message1]

For current purposes, what is interesting is to see how persistent English is even in these few examples: in the case of M37, M38 and M39 (translations in note 13), the English names of lectures, words like ok, lds ‘loads’ and ello ‘hello’. Importantly, these choices are typical also of the colloquial, hybridized ‘Wenglish’ spoken (and indeed written) by many young people in Wales. Although an isolated instance in this corpus, isie ‘eisiau’ (Eng. ‘want’) in M37, is also a Welsh version of precisely the kind of phonological approximations discussed above.

While the kinds of orthographic (or, technically speaking, typographic) choices which young people make in their messages are sociolinguistically and communicatively intelligible, this is not to say that text-messages are without character or interest. Removed from its physical context, M31 is somehow clearly a text-message. How is this? Does this not imply a specific ‘text-message’ genre? All genres and all language are necessarily and always hybrid (see Chandler, 1997, for an overview of genre theory); nonetheless, text-messages are communicative events characterized not only in terms of their linguistic form but also their conversational or interactional function. Although some appear more informational or content-focused, the vast majority of which are clearly relational – so much so, that this solidary function becomes an almost genre-defining rule. Admittedly bearing some resemblance to a single IM (instant messaging) or IRC (internet relay chat) exchange, I suggest that what does give text-messages a distinctive (not unique) generic feel is the combination of (a) their comparatively short length); (b) the relative concentration of non-standard typographic markers; and (b) their regularly ‘small-talk’ content and solidary orientation. Key qualifications here are ‘combination’, ‘comparatively’, ‘concentration’ and ‘regularly’; none of these three features is individually sufficient to characterise text-messaging.

Once again, none of this is intended to suggest that text-messages are functionally unimportant and peripheral, or that they are uniform and strictly formulaic in form. Interactionally speaking, all ‘small-talk’ is ‘big-talk’ (Coupland, 2000). As Androutsopoulos (2000) has demonstrated in the case of ‘fanzines’, non-standard orthography is a powerful but also playful means for young people to affirm their social identities by deviating from conventional forms; in doing so, they differentiate themselves (from adults) and align themselves with each other. To which I would add the opportunity also to personalize and informalize their messages. Text-messages are therefore simultaneously remarkable and unremarkable in their relative unconventionality. The point of this paper, however, is to show how much of what is popularly written and said about text-messaging is often theoretically and empirically unfounded and, more often than not, greatly exaggerated.

Although something of a cliché, it is necessary to acknowledge the speed with which these communication technologies are changing and how academic research in this area slides towards obsolescence before it even gets going. Just as Baron (1998:164) warned of email’s being a ‘technology in transition’, the same is certainly true of mobile telephony and SMS. Not least given its commercial potential, the applications of SMS are being extended all the time – most notably in terms of the still largely untapped potential of internet-mobile phone interfaces (i.e. so called WAP ‘wireless application protocol’ technology). Along with such practical considerations as diminishing consumer charges and increasing commercial advertising, messagers are also increasingly being encouraged into SMS-chat and SMS-dating as well as a host of information services (e.g. news, sports and music) – see, for example, <www.sms.ac>. In this way that the fields of CMC and SMS are themselves beginning to blur. What’s more, just as the text-based nature CMC is changing in the face of ever increasing internet bandwidth, so too is text-messaging poised to become ever more multimodal. Other technical innovations likely to impact of the discourse of text-messaging are more sophisticated predictive text systems and keypad innovations.

Like early theories of CMC, there is often also a tendency to set conventional, face-to-face modes of communication as the ideal – a standard against which technologically-mediated modes of communication must necessarily appear impoverished and inadequate (see Spears et al., 2001). In point of fact, this undervalues the subtlety – and indeed sociality – of technologically-mediated communication and also underestimates the complexity of the interplay between face-to-face and other modes of communication. In much the same way, just as other forms of small talk are erroneously undervalued (Coupland, 2000), in his popular book Language & the Internet, David Crystal (2001) dismisses SMS as simply giving young people something to do – a point of view which seems not only patronising but also underestimates the intricate and integral role text-messaging plays in their social lives.

It is presumably for reasons such as these that, with particular reference to personal communication technology (PCT), Katz & Aakhus’s (2002) have called for more data-driven research and comment. As researchers from the Information Society Research Center attest, however, it is not always easy to access data like text-messages which are almost always private and personal, and sometimes very intimate and often ‘illicit’ (Kasesniemi & Rautiainen, 2002:174). [note 14] In spite of its largely decontextualized linguistic data, the current study offers an empirically-based contribution to growing interest in mobile communication as well as a more critical perspective on the role of new technologies in the lives of young people. In fact, what is evident from the current study is just how blurred the boundary between computer-mediated communication and face-to-face communication really is; for participants, there certainly seems to be little sense in which their text-messaging necessarily replaces face-to-face communication but rather their text-messaging has come to be ‘folded into the warp and woof of life’ (Katz & Aakhus, 2002:12). What is more, just as new linguistic practices are always adaptive and additive rather than substractive, conventional linguistic practices are manipulated with creativity and humour in pursuit of intimacy and social intercourse. However small the participant sample, the current paper demonstrates how sweeping generalizations about ‘what young people do with text-messages’ demand greater scrutiny.

Note 1 Headline quote from BBC News (2000). Text messaging grows up. [Return to text]

Note 2 See also Agence France-Presse. 2002. Wireless net unpopular, text messaging is king. [Return to text]

Note 3 In Germany, one of Western Europe’s greatest SMS-using countries, young people are similarly cast as the ‘handy generation’ (Rössler & Höflich, 2002:10), ‘handy’ being the colloquial German word for a mobile phone. [Return to text]

Note 4 In an article titled Delete text message style, say examiners: ‘Answers peppered with soap opera phrases and written entirely in text message shorthand are posing new challenges for this year's GCSE markers …fears have been expressed that the texting phenomenon could undermine children's grammar.’ (Henry, Julie in the Times Education Supplement, 16 August 2002). [Return to text]

Note 5 Brought to my notice subsequently, Androutsopoulos’s (2000) typology details most of the same features, although labels them differently. [Return to text]

Note 6 Hoping that it was not during lectures given by me, this was by no means the only such example of participants having sent or received messages during lectures! [Return to text]

Note 7 This text-poem was awarded top prize in a well-publicised, national competition run by The Guardian newspaper in 2001. [Return to text]

Note 8 The facility for screening calls is also commonly afforded by answering machines. [Return to text]

Note 9 Counter-claims are often made regarding the concomitant loss of control over one's accessibility and the blurring of the boundaries between public and private. As Katz & Aakhus (2002) comment, 'perpetual contact' has both its negative and positive side. [Return to text]

Note 10 In the context of mobile phones and text-messaging, Rössler & Höflich (2002) characterize this same process as ‘intramedia convergence’. [Return to text]

Note 11 In their paper on the uses and gratifications of mobile phones, Leung & Wei (2000) discuss how mobile phones are ‘more than just talk on the move’. [Return to text]

Note 12 Speaking of the way chain messages may gifted, Ling & Yttri (2000:159) characterise messaging as ‘an updated version of passing notes’; this would seem to be the case for their linguistic form as well. [Return to text]

Note 13 M37 (Welsh): Good morning moz.Sorry for waking you up!Are y (~) coming to the medieval Europe lecture at 2?If yes, d’ya wanna meet in front of the law building at 1:50?Niaxxx; M38 (Welsh): Ello darling.Love you lds; M39(German): Are you ok?.[Return to text]

Note 14 In fact, Baron (1998) makes the same observation about email. [Return to text]

I am especially grateful to Alex Brown for some of her initial coding of the text-messages which she collected with me and spent a lot of time transcribing as part of her undergraduate dissertation; the full findings of Alex’s dissertation (Brown, 2002) have been presented as Thurlow & Brown at ICLASP8 (Hong Kong, July 2002). I am also very grateful to the participants for their time and messages and would like to thank my colleagues, Adam Jaworski and Debbie Morris, for their comments and insights.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis, K. 2000. Non-standard spellings in media texts: The case of German fanzines. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 4(4), 514-533.

Baron, N.S., 1998. Letters by phone or speech by other means: The linguistics of email. Language and Communication 18, 133-170.

[cited]

[cited]

[cited]

[cited]

[cited]

[cited]

Bauer, Martin W. 2000. Classical content analysis: A review. In M. W. Bauer & G. Gaskell (Eds), Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: A practical handbook. Sage, London, pp. 131-151.

Bellis, Mary. 2002. Selling the cell phone.

Brown, Alexandra. (2002). The language and communication of SMS: An exploratory study of young adults’ text-messaging. Unpublished BA dissertation, Cardiff University.

Bryden-Brown, S. 2001, 10 August. Young and free but tied to the mobile. The Australian, pp. 4.

Buckingham, D. 2000. After the death of childhood: Growing up in the age of electronic media. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Calcutt, Andrew. 2001. Generation Txt: Mixed messages.

Cameron, Deborah. 1997. Performing gender identity: Young men’s talk and the construction of heterosexual masculinity. In Sally Johnson and Ulrike H. Meinhof (Eds), Language and masculinity (pp. 47-64). Oxford: Blackwell.

Cameron, Deborah. 1995. Verbal hygiene. London: Routledge.

Carvin, Andy. 2000. Beyond access: Understanding the digital divide. Keynote address to the NYU Third Act Conference, May 19 2000.

Catan, L., Dennison, C. & Coleman, J. 1996. Getting through: effective communication in the teenage years. London: The BT Forum.

Cherny, Lynn. 1999. Conversation and community: Chat in a virtual world. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Collot, Melina & Belmore, Nancy. 1996. Electronic language: A new variety of English. In Susan C. Herring (Ed.), Computer-mediated communication: Linguistic, social and cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 13-28). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Coupland, Justine. (Ed.). 2000. Small talk. Harlow: Longman.

Crystal, D. 2001. Language and the internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[cited]

[cited]

[cited]

Cyberatlas. 2001a SMS Moves Beyond Child's Play.

[cited]

Cyberatlas. 2001b Women Maintain Lead in Internet Use.

Dimmick, J. W., Kline, S. & Stafford, L. 2000. The gratification niches of personal email and the telephone: Competition, displacement and complementarity. Communication Research, 27, 227-248.

[cited]

Eco, Umerto. 2002. Diminutive, but perfectly formed. Guardian Newpaper, 20 April 2002.

Edley, Nigel & Wetherell, Margaret. 1997. Jockeying for position: The construction of masculine identities. Discourse & Society, 8(2), 203-217.

Facer, Keri & Furlong, Ruth. 2001. Beyond the myth of the ‘cyberkid’: Young people at the margins of the information revolution. Journal of Youth Studies, 4(4), 451-469.

Flanagin, Andrew J. & Metzger, Miriam J. 2001. Internet use in the contemporary media environment. Human Communication Research, 27(1), 153-181.

Grice, Herbert P. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Peter Cole and Jerry Morgan (Eds), Syntax and Semantics: Volume 3, Speech Acts. New York: Academic Press.

Griffin, Christine. 1993. Representations of youth: The study of youth and adolescence in Britain and America. Cambridge: Polity.

Hale, Constance. (Ed.). 1996. Wired style: Principles of English usage in the digital age. San Francisco, CA: HardWired.

Halliday, Michael. (1969/1997). Language in a social perspective. In Nikolas Coupland & Adam Jaworski (Eds), Sociolinguistics: A reader and coursebook (pp. 31-38). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Herring, Susan. 2001. Computer-mediated discourse. In Deborah Schiffrin, Deborah Tannen & Heidi E. Hamilton (Eds), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 612-634). Oxford: Blackwell.

Holloway, S. & Valentine, G. 2003. Cyberkids: Children in the information age. London: Routledge.

[cited]

Humphrys, J. 2000. Hell is other people talking webspeak on mobile phones. Sunday Times Newspaper, August 27.

Hutchby, Ian. 2001. Chapter 5: The telephone: Technology of sociability. In Conversation and technology (pp. 80-100). London: Polity.

Jaffe, Alexandra. 2000. Introduction: Non-standard orthography and non-standard speech. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 4(4), 497-513.

Jaworski, Adam. 2000. Silence and small talk. In Justine Coupland (Ed.), Small talk (pp. 110-132). Harlow: Longman.

Kasesniemi, Eija-Liisa & Rautiainen, Pirjo. 2002. Mobile culture of children and teenagers in Findland. In James E. Katz & Mark A. Aakhus (Eds), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance (pp. 170-192). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Katz, James E. & Aakhus, Mark A. 2002a. Introduction: Framing the issue. In James E. Katz & Mark A. Aakhus (Eds), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance (pp. 1-13). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Katz, James E. & Aakhus, Mark A. 2002b. Conclusion: Making meaning of mobiles: A theory of apparatgeist. In James E. Katz & Mark A. Aakhus (Eds), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance (pp. 301-318). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kayany, Joseph M.; Wotring, C. Edward & Forrest, Edward J. 1996. Relational control and interactive media choice in technology-mediated communication situations. Human Communication Research, 22(3), 399-421.

Leung, Louis. & Wei., Ran. 2000. More than just talk on the move: Uses and gratifications of the cellular phone. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(2), 308-320.

Ling, Richard & Yttri, Birgitte. 2002. Hyper-coordination via mobile phones in Norway. In James E. Katz & Mark A. Aakhus (Eds), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance (pp. 139-169). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ling, Richard. 2002. No title. Paper presented at the 52nd Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, Korea, Seoul, 14-19 July 2002.

Livingstone, S. 1998. Mediated childhood: A comparative approach to young people's changing media environment in Europe. European Journal of Communication, 13(4), 435-456.

Malinowski, B. 1923. The problem of meaning in primitive languages. In C. K. Ogden & I. A. Richards (Eds), The meaning of meaning (pp. 146-152). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

[cited]

McQuail, Dennis; Blumler, Jay & Brown, J.R. 1972. Sociology of the mass media. London: Penguin.

[cited]

Noble, Grant. 1987. Disciminating between the intrinsic and instrumental domestic telephone user. Australian Journal of Communication, 11, 63-85.

NOP. 2001a. Half of 7-16s now have a mobile phone. NOP Research Group news.

[cited]

NOP. 2001b. Kids upgrade mobiles. NOP Research Group news.

O’Sullivan, P.B. & Flanagin, A.J. (2000). An interactional reconceptualization of ‘flaming’ and other problematic messages.

[cited]

Palfini, J. 2001. Teenagers do their talking online. PC World, June 21.

Parks, Malcolm R. & Floyd, Kory. 1996.Making friends in cyberspace. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 1(4).

Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2001. Teenage life online: The rise of the instant-message generation and the internet's impact on friendships and family relationships.

Rössler, Patrick & Höfich, Joachim R. 2002. Mobile written communication or email on your cellular phone: Uses of short messaging service SMS by German adolesecents: A pilot study. Paper presented at the 52nd Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, Seoul, 15-19 July 2002.

Shortis, Tim. 2001. The language of ICT: Information and communication technology. London: Routledge.

Spears, R.; Lea, M. and Postmes, T. 2001 Social psychological theories of computer-mediated communication: Social pain or social gain, in W. Peter Robinson and Howard Giles (Eds), The New Handbook of Language and Social Psychology (pp. 601-623). Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

[cited]

[cited]

Teather, D. 2001 Text-messaging Breaks 1bn-a-month Barrier, Guardian newspaper, August 23.

[cited]

Thurlow, C. 2001a. Talkin’ ’bout my communication: Communication awareness in early adolescence. Language Awareness, 10 (2&3), 1-19.

[cited]

[cited]

Thurlow, C. 2001b. Language and the Internet. In R. Mesthrie & R. Asher (Eds), The concise encyclopedia of sociolinguistics. London: Pergamon.

[cited]

[cited]

Thurlow, Crispin & McKay, Susan. 2003, in press. Profiling 'new' communication technologies in adolescence. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 22(1).

Walther, Joseph B. & Parks, Malcolm R. 2002, in press. Cues filtered out, cues filtered in: Computer mediated communication and relationships. In M. L. Knapp, J. A. Daly & G. R. Miller (Eds), The handbook of interpersonal communication (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Walther, Joseph B. 1996. Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3-43.

Werry, Christopher. 1996. Linguistic and interactional features of Internet Relay Chat. In Susan C. Herring (Ed.), Computer-mediated communication: Linguistic, social and cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 47-61). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Witmer, D., & Katzman, S. 1997. On-line smiles: Does gender make a difference in the use of graphic accents? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 2(4).

[cited]

Yates, Simeon. 1996. English in cyberspace. In Sharon Goodman & David Graddol (Eds), Redesigning English: New texts, new identities (pp. 106-140). London: Routledge.