Virtual Scholarship: Navigating Early Modern Studies on the

World Wide Web

Kevin Curran

McGill University

kevin.curran@mcgill.ca

Curran, Kevin. "Virtual Scholarship: Navigating

Early Modern Studies on the World Wide Web". Early Modern Literary

Studies 12.1 (May, 2006) 1.1-23 <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/12-1/currvirt.htm>.

-

The Internet has been a standard presence in the

academy for some time now, but the ever-increasing sense amongst academics

of having a professional obligation to put it to some use is relatively

recent. The question no longer seems to be, “Will I or will I not incorporate

Web-based resources into my teaching and research practices?” but rather,

“How will I incorporate Web-based resources into my teaching and

research practices?” This “how” is a challenging question, even for those

of us who are not new to the world of Humanities computing. As we all know,

even a cursory wander through the scholarly corners of the World Wide Web

turns up a dauntingly profuse array of sites, databases, glossaries, indexes,

texts, image-banks, and other online tools. The overwhelming impression

of copia can be particularly acute for individuals working in early

modern studies, a field that has been at the forefront of academia’s plunge

into cyberspace.

-

So, where does one begin? What is out there? How much of it is useful, and in

what ways is it useful? This essay sets out to begin answering some of these

questions. Conceived loosely as a review article, it undertakes to discuss

a selection of freely-accessible, WWW resources for scholars of early modern

literature. It will comment on some of the specific ways in which WWW resources

are proving valuable to early modern studies and consider what new directions

Web-based scholarship might move in next. This article’s focus on free

websites inevitably excludes some large-scale electronic text repositories

from the discussion: for example, Early English Books Online (http://eebo.chadwyck.com/home)

and the Brown University Women Writers Project (http://www.wwp.brown.edu/).[1]

It should also be noted that the present article does not claim to provide

the exhaustive coverage of an annotated bibliography.[2] It seeks, rather, to establish

a core group of WWW resources that adequately represent the major uses to

which Web-based scholarship is being put. The article will, in addition,

comment on some of the practical, intellectual, and theoretical issues raised

by the use of the Internet in early modern studies and consider what kinds

of challenges these issues might pose to Humanities computing more generally.

Online Journals

-

There are still very few peer-reviewed journals

which are available exclusively on the Internet and which are free of charge.

Those that do exist, however, are among the most frequently used resources

for early modernists currently available on the World Wide Web. Depending

on which one you are dealing with, online journals can foster extreme innovation

or be relatively conservative. Renaissance Forum, for instance, while

maintaining a high scholarly standard, tends to conform to the thematic

and formal norms of a traditional print journal, one which just happens

to be published online instead (http://www.hull.ac.uk/Hull/EL_Web/renforum/).

By contrast, Early Modern Culture: An Electronic Seminar, edited

by Crystal Bartolovich and David Siar (http://eserver.org/emc/),

has from its inception attempted to engage with the cyber revolution of

which it is a part. Designed primarily to feature structured debates in

an essay-and-response format, this simple online resource is an excellent

example of how the immediacy and rapidity of electronic publication can

facilitate new functions for journals. The idea, the editors explain, is

“to create an online space for something like the active and on-going inquiry

of a good seminar.”[3]

No doubt, most of us find the idea of a dubious reader rapidly posting a

response to our work somewhat disconcerting; but we should not lose sight

of the pedagogical value of this kind of interaction. Online journals like

Early Modern Culture bring the intellectual banter of academics into

a forum where students (who are not normally present at our conferences

and colloquiums) can access it.

Electronic Texts

-

Some of the uses to which the Internet has been

put in literary studies were foreseeable from the earliest days of Humanities

computing. The ability of computers to store large amounts of text combined

with the easy access afforded by the World Wide Web opened up a whole range

of new possibilities for disseminating primary-source materials. Richard

Bear was one of the first Renaissance enthusiasts to exploit these potentialities

in the service of creating an online text repository for early modern literature.

Although his pioneering Renascence Editions (http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~rbear/ren.htm)

does not claim to offer true scholarly editions, it is nevertheless

a gargantuan undertaking and provided the impetus for professional academics

to embark on their own electronic-text projects. I will be commenting on

some of these below.

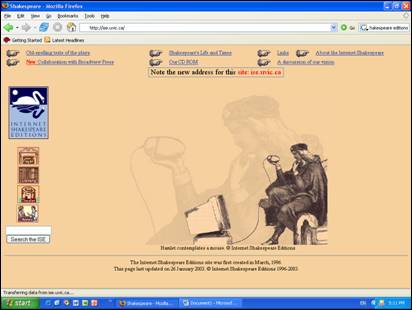

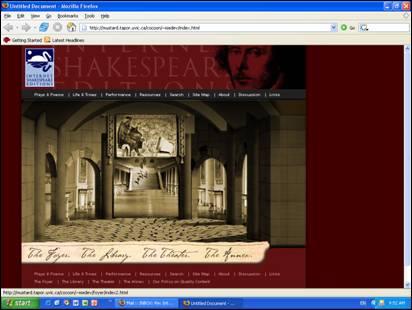

- The obvious place to start this discussion is with Shakespeare, though

one will quickly find that while there is no shortage of Shakespeare resources

on the Internet, almost none of these are dedicated to providing comprehensive

and reliable online editions of his plays and poetry. One of the first Shakespeare

websites, The Works of the Bard (http://www.it.usyd.edu.au/%7Ematty/Shakespeare/),

is an exception, offering full texts of Shakespeare’s complete works, as well

as a slightly antiquated, though still useful, search engine.[4]

It should be said, however, that these texts are not editions per se,

but transcribed text files. Their reliability is limited and should not provide

the basis for any serious academic work on Shakespeare. It is with the nascent

Internet Shakespeare Editions (ISE) project (http://ise.uvic.ca/)

that we find the first concerted effort to present freely-accessible, online

texts of Shakespeare’s complete works which uphold the same rigorous standards

of scholarship displayed in trusted print editions like Arden, Cambridge,

and Oxford. The texts posted on the ISE website will be freshly

edited by well-known Renaissance scholars, under the direction of a prestigious

editorial board. The project will, no doubt, become a benchmark in

twenty-first century Shakespeare studies. For those who have used the ISE

website in the past, it will come as good news that a large-scale redesign

has recently reached completion.[5] The original version of

the site did the project an unfortunate disservice, being both visually unsophisticated

and difficult to navigate. Below are images of the old and new ISE

homepages (Figs. 1 and 2):

Fig. 1. Internet Shakespeare Editions (Old Version)

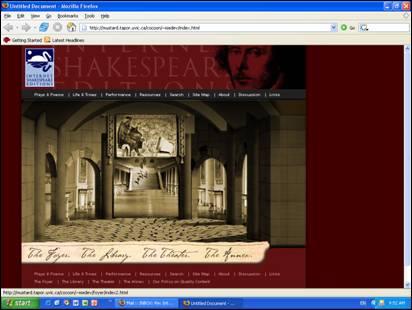

Fig. 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions (New Version)

Fig. 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions (New Version)

Not only is the new version of the ISE interface easier to use

and organizationally more efficient, the aesthetic improvement goes much further

in reassuring users of the scholarly credibility of the ISE venture

as a whole. It seems to me vitally important that Web-based academic projects

- especially those seeking to set new standards for Internet scholarship -

avail themselves of expert design. (More on this topic later.)

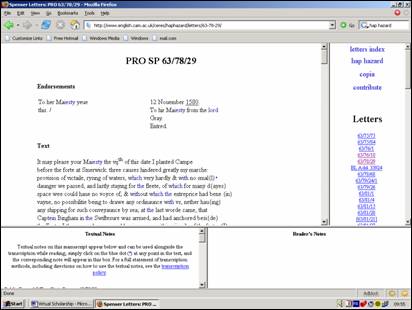

- It is often in slightly smaller-scale endeavors that we encounter

some of the most impressive examples of what can be achieved in electronic

editing. As part of Ceres Online Publications Interactive (COPIA),

for instance, the Cambridge English Renaissance Electronic Service features

Andrew Zurcher’s Hap Hazard: A Manuscript Resource for Spenser Studies

(http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/haphazard/).

This site is home to a number of resources, including an edition-in-progress

of the Gonville and Caius College MS of A View of the Present State of

Ireland, complete with zoomable photographic reproductions of the manuscript

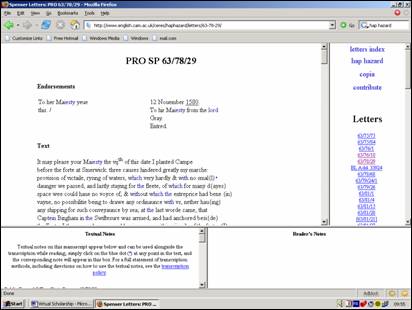

itself. However, the crown jewel of Hap Hazard has to be Zurcher’s

gathering of Spenser’s complete correspondences carried out between 1580 and

1589, the period during which the poet was secretary in Queen Elizabeth’s

administration in Ireland. This first-of-its-kind edited collection includes

an incisive introduction and a compendious bibliography. The letters themselves

have a shrewdly designed, multiple-window interface, allowing the user to

consult notes without having to jump continuously to and from the text (an

inconvenience of printed publication which electronic formats reproduce with

surprising frequency) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Hap Hazard: A Manuscript Resource for Spenser Studies

-

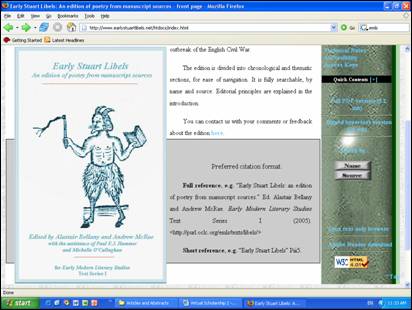

Another example of a highly original and thoughtfully designed repository for

difficult-to-access material is Alastair Bellany and Andrew McRae’s Early

Stuart Libels: An Edition of Poetry from Manuscript Sources (Fig.

8), viewable at http://www.earlystuartlibels.net/htdocs/index.html.

Bellany and McRae’s edition is the inaugural project in EMLS’s

“Texts Series.” Finally, for those interested in Humanistic writings of

the early modern period, the online Philological Museum of the

University of Birmingham’s Shakespeare Institute, overseen by Dana F.

Sutton and Martin Wiggins, holds a wide array of astutely edited English

and Latin texts, all presented in a neat, readable format, with critical

introductions, hyperlinked annotations and, in the case of the Latin texts,

English translations (http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/index.html).

The site also boasts an extraordinary “Analytic Bibliography of Online

Neo-Latin Titles” which presently contains an astounding 14,177 records

(http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/bibliography/index.htm).

Uses for the Database in Early Modern Studies

-

The relentless endeavor to gather information (on

just about anything) and to store it has been going on since antiquity.

Indeed, it could be thought of as something of a human obsession, one which

the computer answered with a never-before-seen capacity for space, speed,

and precision. Storing data of various sorts in an electronic ‘base’ was

one of the first widespread applications to which computers were put, and

the concept seems to have lost none of its efficacy. The field of Renaissance

literature boasts a wide range of useful databases, freely accessible on

the Internet. These range from specialized catalogues, such as Adam Smyth’s

excellent Index of Poetry in Printed Miscellanies, 1640-1682 (http://www.adamsmyth.clara.net)[6]

and The Perdita Project’s expansive bibliography of manuscripts compiled

by early modern women (http://human.ntu.ac.uk/research/perdita/index.html),

to large multimedia text and image archives.

-

Ian Lancashire’s Early Modern English Dictionary Database (EMEDD)

is a superb example of how even a very basic database framework can - if

cleverly deployed – open up new avenues for conducting research (http://chass.utoronto.ca/english/emed/emedd.html).

EMEDD stores full texts of sixteen dictionaries and lexicons published

in England between 1500 and 1660. A quick, precise, and easy-to-use search

engine allows you to look for words in individual texts or in the database

as a whole. The EMEDD provides early modernists with a much-needed

supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary, which can be etymologically

misleading in its preference for literary source material. The database

will be of particular interest to editors and textual scholars.

-

In addition to traditional text databases, academics have found exciting ways

to enrich their electronic archives with multimedia design, especially visuals.[7] Certainly one of the most

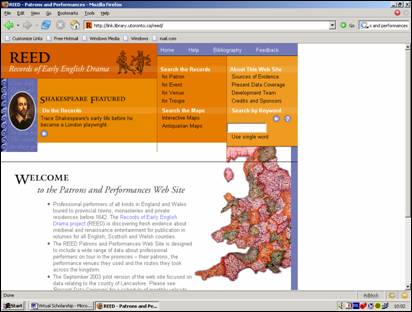

extraordinary examples of this is the Records of Early English Drama

(REED) “Patrons and Performances Web Site” (http://link.library.utoronto.ca/reed/)

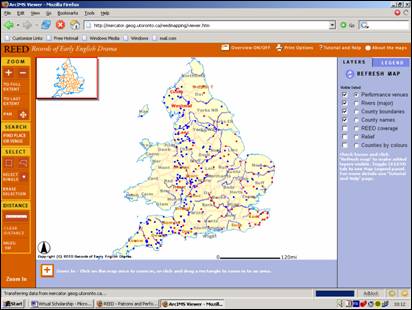

(Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. REED, “Patrons and Performances Website”

REED has since 1975 sought to compile and edit

all the extant documentation pertaining to drama, minstrelsy, and

public ceremony in England before 1642. Starting with York

in 1979, the project has published 25 volumes of dramatic records

extracted from the archives of English towns and counties. The idea

behind the “Patrons and Performances Web Site” is to transfer all

of these records into an electronic database. This process will be

reaching completion over the course of the year 2006, though even

the present pilot version of the database is impressively extensive.

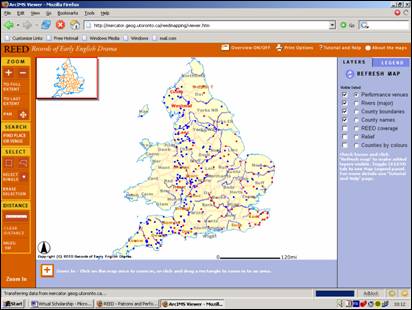

The “Patrons and Performances Web Site” is fully searchable by patron,

event, venue, or acting troupe; it is supplemented with photographs,

portraits, and architectural diagrams, and it features expertly designed

interactive maps that allow the user to pinpoint performance venues

and to chart the itineraries of early performance troupes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. REED, “Patrons and Performances Website” (interactive map)

This database is a truly interdisciplinary

resource, one which admirably exploits the multimedia potentials of

the World Wide Web. The REED “Patrons and Performances Web Site”

is also, without a doubt, the richest repository of documentary evidence

pertaining to Renaissance theatre currently available on the Internet.

-

There are a number of other databases on the World Wide Web that make fruitful

use of both text and image. The curious interplay between pictorial and

orthographic display in Renaissance emblem books beg just such a multimedia

interface. Answering this are several interesting databases dedicated to

emblem literature. One impressive example is The Minerva Britanna Project

(http://f01.middlebury.edu/FS010A/STUDENTS/index.htm),

an online edition of Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna (1612). It

features scanned images of the complete text, shrewd commentaries on each

emblem, and a group of short critical essays. Extraordinarily, this website

and all of its contents was put together by the first-year students of Timothy

Billings’s seminar on “Emblem Literature” at Middlebury College: it stands

as a powerful reminder of the pedagogical uses to which multimedia design

can be put in the Humanities.

-

Another noteworthy emblem-book database comprises the core of the Penn State

University English Emblem Book Project (http://emblem.libraries.psu.edu/home.htm).

This website allows users to browse page-by-page through a choice of nine

early modern emblem books held at the Penn State University Library. It

includes a useful discussion on the role of emblem books in Renaissance

culture (pitched at undergraduate level), as well as a sizable list of print

and hypermedia resources for emblem studies. The website is, unfortunately,

poorly served by a cranky search engine which only allows for the most basic

queries. This is not too much of an obstacle at present since the database

is still relatively small and easy enough to browse manually. It may, however,

become aggravating as the database grows. (It will eventually hold a collection

of emblem books dating from the sixteenth all the way up to the nineteenth

century.)[8]

-

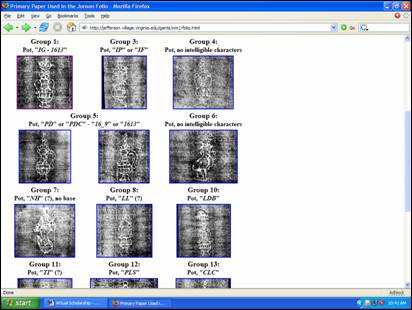

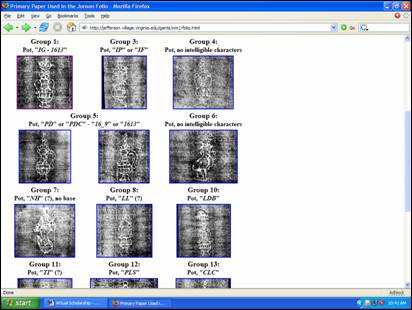

Before closing this section on databases, I should mention the particularly remarkable

Digital Catalogue of Watermarks and Type Ornaments Used by William Stansby

in the Printing of “The Workes of Benjamin Jonson” (1616) (http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/gants/Folio.html).

This highly specialized multimedia archive – currently nearing completion

- was constructed under the direction of David Gants at the Institute for

Advanced Technology in the Humanities, University of Virginia, home to such

notable multimedia databases as The Abraham Cowley Text and Image Archive

(http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/kinney/)

and Ovid Illustrated: The Renaissance Reception of Ovid in Image and

Text (http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/latin/ovid/ovidillust.html).

As Gants explains in the “About This Project” section of the website, the

Digital Catalogue “aims to create a model archive for the storage

and circulation of material evidence concerning the printing industry in

late Tudor and early Stuart London.” The website is organized under a series

of menu headings dedicated to the different types of paper and printers’

ornaments used in the production of Jonson’s 1616 folio. There is also an

“Index to Works,” and a “Brief Biography” of Stansby. In the paper sections,

the user is presented with low-resolution images of the watermarks that

designate each paper-group (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Digital Catalogue of Watermarks and Type Ornaments Used by William

Stansby in the Printing of “The Workes of Benjamin Jonson” (1616)

Clicking on any watermark image brings

you to a detailed specifications page, listing the exact dimensions

of both watermark and paper. Beneath this is a list of the years

in which the given paper was used in Stansby’s shop; each year

is hyperlinked to an expanded bibliographical entry in the “Index

of Works” section. Simple, but shrewd. This is a database which,

despite its specialist content, is easy to use and, most importantly,

easy to learn from.

-

No doubt one of the Internet’s most precious contributions

to scholarship of the early modern period has been in the field of manuscript

studies. While it is commonly held that an intimate understanding of early

modern literary culture is only possible if one becomes conversant with

the period’s various textual media, for many, learning about manuscript

writing presents a crux in that it is dependent upon either being fortunate

enough to work at or near one of the few institutions with a good early

modern manuscript collection or, alternatively, upon being able to secure

the time and grant money needed to visit those institutions. What we have

now, however, is a small group of websites that make it possible to consult

a selection of early modern manuscripts online. For anyone relying heavily

on manuscript sources in their research, these websites will not, of course,

alleviate the necessity of visiting the appropriate libraries and archives.

What they do offer is an invaluable opportunity for beginners to attain

a basic level of competency before setting off to consult actual manuscripts

in situ.

-

Different manuscript websites offer different services.

If you simply want to consult manuscripts, Oxford University has an excellent

Early Manuscripts site which showcases a sizable collection of high-resolution

images of mostly, though not exclusively, literary manuscripts housed at

the Bodleian Library and some of the older Oxford colleges (http://image.ox.ac.uk/list?collection=all).

A great deal of the collection dates from slightly before our period, but

there is enough Renaissance material to make the site worth mentioning.

For a specialized website dealing with manuscript annotations of printed

Shakespeare texts, see Shakespearean Prompt-Books of the Seventeenth

Century (http://etext.virginia.edu/bsuva/promptbook/index.html).

Edited by G. Blakemore Evans under the auspices of the Bibliographical Society

of the University of Virginia, the website presents a wide array of early

printed texts of Shakespeare’s plays which have been marked up by contemporary

hands for stage production. It is an indispensable resource for those interested

in the history of early Shakespearean performance practices, and though

it is not the most visually attractive website it is intelligently designed

and relatively simple to navigate.

-

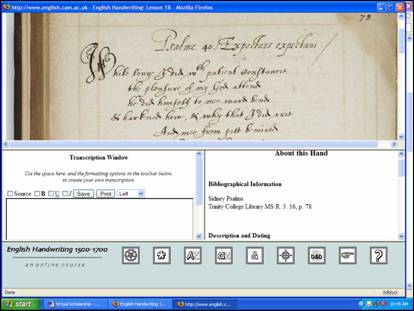

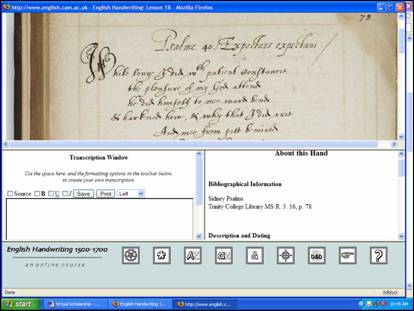

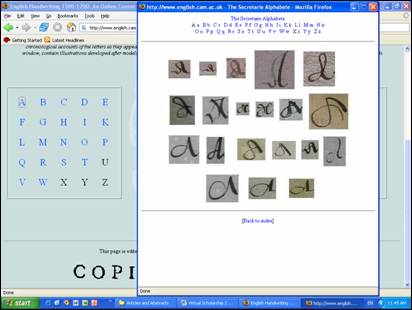

By far the most outstanding manuscript resource on the World Wide Web is English

Handwriting, 1500-1700: An Online Course (http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/ehoc/).[9]

Here, hats must go off once again to Andrew Zurcher who designed and continues

to maintain this site as part of COPIA. Drawing on a massive archive

of high-resolution images of manuscripts from Cambridge University, English

Handwriting offers a total of 28 lessons in transcription, all ranked

in difficulty on a scale of one to five. That these lessons are so effective

has a lot to do, I think, with the ingenious design of the website (Fig.

7).

Fig. 7. English Handwriting, 1500-1700: An Online Course

Choosing a lesson brings you to the lesson

interface: in one window – the largest – you have a high-res,

zoomable image of the manuscript that you will be working with;

another window provides a space for you to type your transcription;

yet another displays information “About this Hand,” including

bibliographical details, description, and dating. A menu of symbols

lines the bottom of the interface; clicking on them allows the

user at any point during their transcription to, for example,

view a sample transcription, take a test on the transcription,

view an upper or lower-case alphabet, see a table of common brevigraphs

and abbreviations, zoom in on the manuscript image, view some

notes on dating and describing the given hand, or view other manuscripts

in the same hand. This website is a remarkably generous undertaking;

if used properly, it is highly effective in instilling even a

complete beginner with basic paleographical skills.

Sound

-

It seems only appropriate to include a few words

on sound. The Internet has, after all, permitted scholars to explore the

medium of sound in a way never before possible with print. In addition to

the many early music resources now available on the World Wide Web,[10] there have been valuable

attempts to investigate links between sound and literary culture. Early

Modern Literary Studies, for example, has produced a special

issue on “Listening to the Early Modern,” in which six articles consider

how sound can function as a category of critical enquiry in early modern

studies. In the article, “Hearing Green: Logomarginality in Hamlet,”

Bruce Smith embeds actual sound files into his text in order to recreate

the acoustic matrix within which the character Hamlet would have defined

himself in the original Globe Theater production (http://www.shu.ac.uk/emls/07-1/logomarg/intro.htm).

We find another astute exploitation of the Internet’s sonic capabilities

on the COPIA website at Cambridge University. Sidneiana, a

resource for manuscript-based research relating to Sir Philip Sidney and

his circle, features musical reconstructions of Philip Sidney’s Certain

Sonnets 6 and Robert Sidney’s Song 12, complete with sound files

(http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/sidneiana/songs.htm).

Ventures such Bruce Smith’s “Hearing Green” and COPIA’s Sidneiana

highlight the intellectual applicability of the Internet in the most salient

terms. For they testify not merely to how the World Wide Web changes the

medium through which we produce and consume scholarly work, but to how this

medium permits us to enquire into cultural phenomena (such as aural experience)

which would otherwise remain at the margins of early modern studies.

Futures of Web-Based Scholarship

-

What are the futures for the World Wide Web in

early modern studies? One functionality of the Internet which has not yet

been as widely drawn upon as hypertext, digitally scanned images, or sound,

is video. And yet in the relatively small number of places where we do find

video being deployed in our field, its pedagogical merits are strongly manifest.

Alan Liu, for instance, webmaster of the vast Humanities website, Voice

of the Shuttle (http://vos.ucsb.edu/),

features on his homepage a number of links to webcasts of important talks

he has given (http://vos.ucsb.edu/liu-profile.asp).

There is also the “English Web Video Page” hosted by Arizona State University

(http://www.asu.edu/english/video).

As well as presenting video files of departmental presentations on literary

topics, the Web page archives “Professional Development Workshops,” in which

faculty members advise audiences of advanced graduate students and junior

faculty members on the academic job market. This latter resource will be

of particular utility for someone who, for example, did their graduate studies

in the UK but would like to work in North America. The “English Web and

Video Page” provides an insider’s view into the kinds of expectations and

protocols that underlie the North American job market. Finally, the Shakespeare

Moot Court Project at McGill University – a radical attempt to find new

formats for teaching students about the relationship between language and

cultural value - is supported by a website that includes a video archive

of past trials (http://www.mcgill.ca/shakespearemoot/).

Here, the medium of video plays a key role in conveying to a wider academic

community an important experiment in education, one which may not be fully

communicable in a written description alone. It is hoped that the use of

video technologies in early modern studies will continue to be expanded

in years to come.

-

Technological advance, however, is only one aspect

of what will be involved in ensuring a progressive evolution for Web-based

scholarship. There are also some important practical and theoretical issues

which will need to be addressed. In the websites that have been considered

here, I have been particularly struck by the extent to which the scholarly

integrity of an online resource is affected by the design of its interface.

The old Internet Shakespeare Editions website provides a perfect

example of how a crude and confusing interface can unjustly diminish the

sound scholarship that lies just beneath it. This is a new kind of problem

for academics. In the case of printed books, establishing credibility has

very little to do with interface. When someone tells us not to judge a book

by its cover, this makes sense as piece of proverbial wisdom because we

know – at least in the case of academic publishing - that what lies behind

that cover will adhere to a relatively standard set of organizational criteria.

This allows us to evaluate the intellectual content of a book in its own

right, without having to be too concerned with how that content is being

mediated. Digital interfaces, by contrast, are so varied and unpredictable

that basic levels of formal coherence cannot be taken for granted. This

changes our normal processes of scholarly assessment. Intellectual merit

becomes much more difficult to judge in isolation from its mode of delivery.

In cyber-space, form and content exist in a far more closely bound up relationship

than they do in the world of print-based knowledge. Designers of academic

websites need to be responsive to this, taking particular care to communicate

the scholarly integrity of their resource through its interface. Towards

this end, it seems essential that the international academic community eventually

decide upon some shared set of criteria for organizing and designing their

websites

- Another issue which I have seen emerge from this survey has to do

with the handling of images. Some websites are very thorough in their documentation

of pictorial material. REED, for instance, appears to be acutely aware

of the status of their pictures as material evidence. The paintings, antiquarian

maps, and ground plans that have been incorporated into the Web pages are

treated with the same respect for origin and historical context as any textual

matter. The same can be said of the images of watermarks in David Gants’s

Digital Catalogue of Watermarks Used by William Stansby. But not all

academic websites display such documentary scrupulousness. Sometimes images

from early modern texts are used more as decoration than as evidence. This

is the case of the satyr-figure we find on the Early Stuart Libels homepage

(Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Early Stuart Libels Database: An Edition of Poetry from Manuscript

Sources

Is this a problem? Do we need to establish a more

firm set of criteria for the use of images on scholarly websites? Part

of me is tempted to answer “yes,” if only for the sake of upholding

a certain standard of documentary consistency in Web-based scholarship.

But actually applying such criteria would be less straightforward than

it might seem. Things become complicated when we consider a website

like English Handwriting, 1500-1700, in particular the sample

alphabet that Zurcher has constructed from various manuscript sources

(Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Letter “a” from English Handwriting, 1500-1700: An Online Course

For none of these “a” images is textual provenance

recorded; but I believe the omission was a wise decision. Demanding

copious documentation in this case would just clutter the website,

detracting from its coherence and, ultimately, its utility. The

manuscript alphabet shows Zurcher doing exactly what he should

be doing as a Web-designer/scholar: exploiting the vast visual

possibilities afforded by Web-design to make a better pedagogical

tool.

-

Image handling, then, is a vexed issue. While shared standards of documentation

are needed if we intend to use and trust Internet projects in the same way

we do printed books, the essentially visual nature of Web-based knowledge

can make such a demand seem counterproductive from a practical point of

view. Equally vexed is the matter of interface design. For while it is of

paramount importance that academics establish some system of structural

and visual standardization for their websites, the diversity of uses to

which Internet scholarship is being put will make agreeing on such standards

an extremely difficult task. It is, nevertheless, crucial that we take these

matters seriously. A first - if modest - step in that direction might be

simply to acknowledge interface design and image-handling as concerns which

are consequential to the future of Web-based scholarship, and to

begin thinking about how these issues might be addressed as Humanities computing

moves into its next phase.

Some Closing Words

-

The primary purpose of this article has been to

gesture towards the variety of uses to which the Internet is being put in

our field, with the underlying goal of helping early modernists locate WWW

resources that connect meaningfully to their own teaching and research interests.

Successfully navigating early modern studies on the World Wide Web does

not mean trading one form of scholarly practice for another, newer one:

it does not entail making a break from print-based scholarship. Resources

such as Open Source Shakespeare or Internet

Shakespeare Editions, for instance, do not stake

their claim to our attention by being categorically ‘better’ than print

editions from a textual or intellectual point of view. Rather, their usefulness

lies in the fact that they possess functionalities which print editions

do not have, and therefore represent a constructive adjunct to the print

editions on the market. Likewise, the online paleography course, English

Handwriting: 1500-1700, does not aim to replace or minimize the need

to consult actual manuscripts in archives and research libraries. To the

contrary, it seeks to encourage academics to continue working on location

with primary sources by instilling in them the basic skills and confidence

needed to do so. Navigating early modern studies on the World Wide Web,

then, is about finding constructive continuities between traditional and

technologically more progressive forms of scholarship; it involves building

upon already-existent foundations of intellectual enquiry rather than obliterating

or revolutionizing those foundations. Indeed, the most impressive Internet

projects considered in this article – sites like the REED “Patrons

and Performances Web Site,” English Handwriting, or the Digital

Catalogue of Watermarks Used by William Stansby – were undertaken by

academics, or teams of academics, who have strong groundings in time-honored

fields such as bibliography, paleography, and book history. These resources

issue a valuable reminder that the Internet is not just creating new disciplines

for early modernists to delve into, but helping old disciplines to move

forward in exiting ways.

-

Our present position in the world of Web-based scholarship might aptly be compared

to the position of textual editing at the turn of the twentieth century:

a great deal of important work has been done, but all in the absence of

any real formal, procedural, or scholarly standards. Finding ways of agreeing

upon and implementing such criteria may very well prove to be one of the

key challenges facing Humanities computing in the future.

Special thanks to Alastair Bellany and Andrew

McRae, Michael Best, David Gants, Sally-Beth MacLean, and Andrew Zurcher

for permission to use screen shots from their respective websites. Thanks

as well to Katherine Acheson for helpful feedback on an earlier draft of

this essay.

[1]

A useful review of Early English Books Online was written by Gabriel

Egan and John Jowett. See “Review of the Early English Books Online (EEBO).”

Interactive Early Modern Literary Studies (January, 2001): 1-13 <URL:

http://purl.oclc.org/emls/iemls/reviews/jowetteebo.htm>.

For the Brown University Women Writers Project, see Elizabeth Hagglund,

“Review of the Brown University Women Writers Project and the Perdita Project.”

Interactive Early Modern Literary Studies (May, 2000): 1-9 <URL:

http://purl.oclc.org/emls/iemls/reviews/hagglund.htm>.

[4]

For an extremely advanced search engine, go to the excellent Open Source

Shakespeare site, where you can search with precision across all or

parts of Shakespeare’s canon for anything from individual words to individual

characters’ lines (http://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/).

[5]

My gratitude to Michael Best, Coordinating Editor of the ISE project,

for generously supplying me with URLs that gave me a sneak preview of the

new interface before it was up and running.

[6]

A detailed description and discussion of this website is supplied

by Adam Smyth, “An Online Index of Poetry in Printed Miscellanies, 1640-1682.”

Early Modern Literary Studies 8. 1 (May, 2002): 5.1-9<URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/08-1/smyth.htm>.

[7]

My discussion of multimedia databases would, of course, have to be greatly

expanded if resources for historians of Renaissance art were included. This

essay confines itself to the field of literary studies, but for readers

who are interested in consulting art history websites, the following links

provide good listings: Art History Resources on the Web (http://witcombe.sbc.edu/ARTHLinks.html);

the Art and Architecture section of EMLS’s “WWW-Accessible Resources”

page (http://www.shu.ac.uk/emls/emlsweb.html).

[8]

For an emblem book database with a much more advanced search engine – and

one serving a much larger collection – see the Emblem Books in Leiden

website (http://www.etcl.nl:8080/book-publ/emblem/).

Unlike the English Emblem Book Project, however, this is not a multimedia

archive, but a bibliographic catalogue.