The use of Virtual Research Environments and eScience to enhance use of online resources: the History of Political Discourse VRE Project

Simon

Hodson

University of Hull, University of East Anglia

Simon Hodson. "The use of Virtual Research Environments and eScience to enhance use of online resources: the History of Political Discourse VRE Project.". Early Modern Literary Studies 14.2/Special Issue 17 (September, 2008) 4.1-39 <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/14-2/Hodsvirt.html>.

Introduction

- The

purpose of this paper is to suggest that new technologies and practices

associated with Virtual Research Environments (VREs) and eScience communication

techniques can enhance the already considerable benefits which resources such

as EEBO have brought to the study of early modern texts and their contexts. It

reports on the innovative work of a consortium comprising the University of

Hull and the University of East Anglia (both UK), implementing such

technologies in the delivery of a jointly-taught MA Programme and in the

practice of a dispersed Research Group studying early-modern political discourse.

A third, still largely aspirational programme, suggests ways in which such

technology may be used for large-scale collaboration by EEBO-using scholars.

Scholarly developments in the history of political discourse and the study of early modern texts

- What

is the scholarly and research need for the use of VREs and eScience techniques

for the study of the history of political discourse? Recent developments in

the history of political thought have transformed that discipline from the

history of political ideas tout court, to the history of political

discourses. By this we mean that although the study of canonical texts has not

been abandoned, it has been transformed by a greater awareness of the context,

the broad cultural milieu in which they were created. This has been

accompanied by an active engagement with other forms of expression and cultural

products: encompassing those produced by non-elite and marginalized groups,

those produced in other genres or media, ranging from popular printed

‘ephemera’, broadsheets, pamphlets and songs, court depositions, visual sources

of various sorts through to rituals and gestures. All these forms of

expression provide evidence of political discourse, in the broad sense towards

which that term drives. They provide context and counterpoint to the ideas

laid out by more formal theorists or professional politicians. Important

methodological features of this process might be characterised thus:

- The need for cultural products expressing political ideas to be fully contextualised in order to be properly understood has been accepted. But in turn, this gives rise to necessary but challenging debates about the relative significance and the interelation of a plurality of contexts: whether diachronic or synchronic, religious, economic, cultural, social, gender-based etc, as well as the social dynamics of expression, covering affective, friendship, patron-client, household, village, state….

- The methodological realisation, best enunciated perhaps by Reinhart Koselleck and the continental school of conceptual historians, that social history is necessarily a history of concepts, and a history of concepts is necessarily a study of discourse and language.[1]

- The

‘linguistic turn’ taken by historians of political ideas, and an expanding appreciation

of literary forms and genres, has been met by a new historicism in the study of

literary texts.

- The

upshot of these developments is an erosion of boundaries between hitherto

discrete approaches and the creation of a fertile interdisciplinarity. This

makes for an exciting period in this branch of history. Above all, as I have

indicated, historians of political discourse are increasingly ambitious in

terms of the range and variety of sources they feel it is necessary to bring to

bear on the subject. This in turn has created a demand for collaborative

scholarship in order best to combine complementary approaches to different

sources and sets of evidence, and in order to encourage genuinely comparative

studies of the interrelation of text and contexts. What is more, a lot of

innovative work has been encouraged by the increased availability of a wide

range of digital resources.

The explosion in digital resources

- The

creation of large databases providing access to digital resources has been an

incredibly exciting development for historians of all stripes. There are

innumerable such resources and their impact has surely been immense. For

historians with an interest in early modern texts, the most important are Early

English Books Online (EEBO) and Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO),

both of which are commercial endeavours. Between them one can access from

one’s desktop almost any printed work produced in these Islands between roughly

1480 and 1800. It is an astonishing resource. In the UK, the creation of

digital resources for history by Arts and Humanities Research Council funded

projects has also been significant: take the Newton project, or the Hartlib

Papers. The international dimensions of digital resource creation also

deserves mention. Privately-funded American databases such as the Liberty and

Constitution online libraries are extremely useful. And, as an historian with

European interests I would also like to mention Gallica, provided by the

Bibliothèque national de France[2]

and a remarkable Spanish project, La biblioteca virtuel Saavredra Fajardo de

pensamiento politico,[3]

which provides eBooks, archival facsimiles, etc.

- The

immediate availability of the sources in such collections has undoubtedly had a

transformative effect on scholarship and pedagogy. In the history of political

discourse, resources such as EEBO have amplified the significant interpretative

and methodological trends which I have already mentioned. The ready

availability of pamphlets, ephemera and the textual records of various ‘lost’

voices have accentuated the debate over ‘which context matters’ and further

contributed to the shattering (or diversification) of the canon. Likewise, for

example, the ease with which students and scholars might access contemporary

translations (as opposed to modern critical editions) has arguably turned minds

further towards the re-packaging, reception and re-reading of certain texts (as

opposed simply to their ‘production’). Finally, in the case of EEBO, as the

work of the Text Creation Partnership progresses the prospect of an expanding

corpus of full-text, key-word searchable documents offers implications of an

transformative nature, holding out the possibility of collaboration with corpus

linguists and the integration of their techniques with more traditional methods

of textual analysis. What is the best way to react to and exploit these

developments? This is the question our VRE project has sought to offer some

preliminary answers.

What is a VRE?

- The UK Working Group on Virtual Research Communities for the OST e-Infrastructure Steering Group offered a useful definition of a VRE.

- Connecting large, disparate, data sets (raising questions of their interoperability, use of medadata standards, ontologies and other challenges – including those of funding and use – inhibiting their creation.

- Connecting historians and data, returning again to the notion that VREs/MREs/portals can enhance the way historians interact with data sets and online resources.

- Connecting

historians with each other, holding out the prospect of increased

collaboration between geographically dispersed researchers, or simply

between historians who which to work collaboratively and cumulatively on

the same data sets and resources.[6]

- Each

of these connections has considerable virtue and potential. Although they

necessarily impinge upon and affect each other, the project upon which I work

has been interested above all in the last two ‘connections’. We see our VRE

primarily as facilitating and aiding collaborative research, and to do

this by connecting scholars or students working largely – but not exclusively –

on digitally available resources such as EEBO. The corollary of this, which I

want to be stressed at the outset is our project’s view, in line with that

expressed by the VRC’s Working Group, is that creating and implementing a VRE,

must comprise creating a Virtual Research Community. And it is precisely this

that we have set out to do in through the creation of a ‘VRE for the History of

Political Discourse’, and what we have called the ‘Early Modern VRE Research

Group’. Our project’s activities seek above all to address the emerging

research agendas within in the subject area, it seeks to exploit an occazione

provided by conjunctura of collaborative technologies and digital

resources. Might such creative alchemy have a transformative effect on

research practice and outputs? This is what we have set out to explore.

The VRE for the History of Political discourse

- The

VRE for the History of Political Discourse[7] project received initial funding from the UK’s Joint Information Systems Committee

(JISC) and then a further grant, explicitly to expand our work, from the

British Academy. This funding has allowed us to explore the potential for

collaborative research in our sub-discipline. We have explored the use of two

main technological solutions through three associated strands of activity.

Technologies: Access Grid and Sakai

- Access

Grid[8] is a form of web-based video-conferencing which can be used to run seminars

between geographically dispersed researchers. It can operate from fully kitted-out

rooms, with four cameras and a full wall of projection, or from a desktop node,

or PIG. By using it in conjunction with something called VNC (Virtual Network

Computing) such meetings can be enhanced with shared document viewing. Access

Grid has open-source and commercial variants: we have preferred the commercial

solution provided by inSORS, based in Chicago. However, we collaborate

regularly with users of the open source alternative.

- Sakai[9] is a web-based collaborative environment which at first glance shares many

features associated with Virtual Learning Environments. But as open-source

software, created by a large international consortium and foundation and

engagement from major educational institutions, it has the potential to become

very much more than that. The integration of a wiki tool indicates there is

good reason for believing in that potential. In the medium term, the expressed

aims of achieving forms of integration between Sakai and Portal and Portlet

technology – and with data repositories – promises a host of useful

collaborative and research tools.

Three Strands of Activity

- Our initial funding, from the JISC was to establish the MA in the History of Political Discourse, using VRE and eScience technology to allow collaborative teaching between the University of Hull and UEA. We use Access Grid to run joint seminars in the core units or modules; and we support the students’ learning experience with our Sakai VRE. The emphasis in the MA’s pedagogy is upon the acquisition of up-to-the minute research skills. As much as is possible, we encourage the students to take ownership of their virtual space and use it for collaboration.

- Extra funding from the British Academy was given explicitly to expand our activities and our VRE through creating a Research Group using collaborative technologies to advance their work. The Early Modern VRE Research Group uses Access Grid to hold monthly research seminars and uses Sakai for asynchronous collaboration. Our aim has been to encourage established, world-class scholars to take advantage of technology with which they have hitherto had little experience. The current project has taken the working title: Different constructions of the Commonwealth and polity. It’s purpose to develop a rich collaborative and synthetic analysis of certain key terms in early modern political discourse, including Republic, Commonwealth and their cognates. The project is explicitly a pilot for a larger scale collaboration on a broader set of keyword/concepts, for which we have applied for AHRC funding.

- The third

strand of activity is more aspirational in nature. It seeks to pilot the use

of Sakai to support a large scale community research forum. Scoping exercises

have been held and gaps identified. We think that there is community

enthusiasm for a large scale collaborative portal, but, in the case of Sakai at

least, further technological progress is required before function truly

coincides with aspiration.

- All

of these strands of activity make considerable use of digital resources in

general and EEBO in particular. As they each focus on a different type of

Virtual Research Community, our implementation and use of the technology has

been adapted in each case in ways which I shall describe.

MA in the history of political discourse

- The

MA in the History of Political Discourse 1500-1800[10] was piloted in the academic year 2005-6 and is now being run for the first time

as a full programme with an external examiner. Three core units are taught in

full collaboration using Access Grid for weekly seminars and the Sakai VRE for

seminar preparation and follow-up. Authority and Ideology in Seventeenth

Century England is led by UEA; Obedience and Dissent in the Age for

Renaissance and Reformation, a module with a more European perspective, is

taught from Hull; and a unit of Historiography and Methodology in the

history of political discourse is a full blown collaboration in its conception

and teaching. The potential here is for modules and programmes to be run

across institutions, giving students access to a greater range of expertise and

a greater variety of course content. It is hoped, from an institutional level,

that this will allow niche subject areas to enhance their viability in

hard-pressed times by permitting pooled seminars.

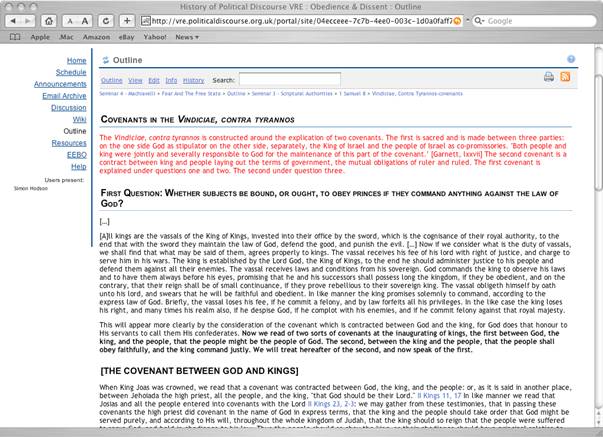

- Both

in terms of managing Access Grid Seminars and in using effectively the Sakai

portal, the MA programme has provided us with useful experience and insights.

All the course materials are provided electronically: all texts or images to be

studied are obtained from online sources, primarily EEBO. We have used the VRE

to make full-text extracts or sections of facsimiles in PDF available to the

students as appropriate. The work of compiling selections and images to create

these resources has been considerable, but has been essential to the success of

the programme. Here, as elsewhere, student feedback as been extremely

positive. The Sakai Wiki has been used to provide an attractive and easily

manipulable interface for access to these resources. The students are required

to use the Discussion Board to exchange ideas in advance of the joint seminar.

These comments are then fed directly into seminar content. More detailed

presentations and textual elucidations are made in the Wiki. The portal is used

directly in seminars to view comments, documents etc. We have sought at all

stages to put the accent upon a research-centred, student-led pedagogy, one

which enhances the use of the digital resources at our disposal and equips the

students with up-to-the-minute research techniques appropriate to a rapidly

evolving discipline. Three features of our experience are worthy of particular

mention.

Student Ownership of the VRE

- As

much as possible we tried to encourage the students to take ownership of their Collaborative Environment. And to a large extent they have risen to this

challenge. Their use of the discussion board in particular has been excellent

and has provided a real kick-start to the seminars. When more in-depth

research was called for in the context of student-led follow-up seminars,

students have used the VRE to share their research. The environment has

allowed them to make digital resources available to their colleagues, to use

the Discussion Board or the Wiki to communicate their papers and present them

to the group in Seminars. This has been most successful in seminars on Civil

War Radicalism where research exercises focussing on Petitioning and the

activities of the Levellers have encouraged excellent use of EEBO and the VRE

for primary research and collaboration.

Figure 1: Use of the Sakai Wiki for textual analysis

Enhancement of Digital Resources and Joint Visualisation

- Access

Grid allows the sharing of PowerPoint presentations and this has been used

successfully in a number of seminars. Even more interesting, however, is the

use of VNC (Virtual Network Computing) to provide shared access to

jointly-viewed documents, made available through the collaborative environment

or it might be obtained directly from a web-based resource such as EEBO. This

was used very successfully to allow close textual analysis and discussion and

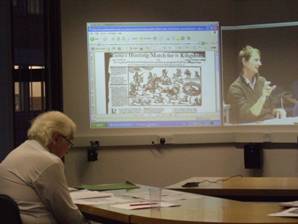

even the comparison of analogous texts. Below we see the view from Hull of a

seminar, led by Dr Mark Knights at UEA, in which the students are discussing

the indeterminacy or ambiguity of meaning in early modern printed texts, and

paying particular attention to the insights to be drawn from the title page

engraving displayed to both sites. The text under discussion is an anonymous

pamphlet Rome’s Hunting Match for Three Kingdoms,[11]

part of a web of polemics and parodies which call into question the nature of

truth in political argument.

Figure 2: Joint Visualisation in an MA Seminar: Rome’s Hunting Match for Three Kingdoms

- All

our MA seminars use the VNC link to provide shared visualization of the texts

and/or images under discussion, or to display tudent contributions to the

Discussion Board and Wiki. In a subject which requires tight argumentation and

disciplined conceptualization, such an exercise is extremely useful. We think

this is innovative pedagogy and has been very successful. But at the same

time, we think that only the ice-berg tip of its potential has been realised.

It would be nice to make more of this shared visualisation, comparisons between

many texts and the potential for collaborative annotations and glosses before,

during and after the seminars.

EEBO and e-Research seminars: the Vindiciae…

- In

one seminar on theories of resistance we took a seminal text:

Duplessis-Mornay’s Vindiciae contra tyrannos: known in its English

translations as A defence of liberty against tyrants.[12]

We discussed the context of its composition following the Massacre of Saint

Bartholomew’s night during the French Wars of Religion [1574-6]; we discussed

the Dutch context of its publication as a justification of William the Silent’s

revolt against the Spanish [1579]; and we examined the various contexts to its

numerous English translations and republications. All the while, we looked at

the various discourses which influenced the author and were deployed,

manipulated and reconfigured in the various incarnations of its text: among

them Aristotle’s Politics and his definition of the tyrant, Roman Law

and various Biblical texts, in particular 1 Samuel 8, particularly as conveyed

through the Geneva Bible and its marginal commentaries.[13]

- Such

an approach is in line with the most recent research, equally transformed by

the advent of EEBO. Take for example, Anne McLaren’s reinterpretation of the Vindiciae,[14] in which she rejects what she describes as the (over-)emphasis on Roman law

bequeathed by the interpretations of Skinner and Garnett. One does not have to

agree with all the arguments advanced – one might observe, for example, that

when an author cites a biblical source, the argument being advanced is not

necessarily a religious one, one might dispute which genre of discourse does

the most significant work – to recognise that the methodology she

applies is significant, transformative and infused with the excitement of

possibilities glimpsed since ‘the advent of Early English Books Online’.[15]

Above all, her work is effective in its examination of the English ‘reception’

and ‘translations’ of the Vindiciae, raising pertinent questions about

the use of contemporary reading(s) to discover the meaning(s) of text and/or

authorial intention(s). McLaren explicitly acknowledges the role that EEBO

played in allowing her more readily to compare various contemporary

translations of the texts and the supporting structure of texts which formed the

context for early-modern ‘reading’.

- In

somewhat less detail, a comparable approach was followed in the UEA-Hull

seminars, and it is one with which the students engaged exceptionally well,

participating outstandingly outstandingly well in the seminar and its

preparation. The technological platforms used to support the seminar may not

have been precisely a sine qua non of this approach, but they certainly

helped. The Access Grid platform allowed Colin Davis in Norwich and, as a

guest tutor, Mark Greengrass in Sheffield to lend their expertise in the

elucidation of English and French contexts, respectively. And Sakai provided

an environment in which the students were given ready access to the selections

made from various sources, all available digitally, and allowed them to offer

their comments and interpretations in good time before the seminar.

User feedback

- We

have sought feedback from students and tutors at regular intervals through

informal discussion and by means of questionnaires. The pilot year was

hampered by a few technical and organizational problems and this had an effect

on student confidence, with some feedback relaying their self-consciousness and

intimidation when confronted by unfamiliar technology. This year, as a result

of accumulated experience we have been better able to make the technology

disappear and the joint seminars have run extremely well. Similarly successive

improvements – aesthetic and functional – in the Sakai interface have

substantially improved students’ experience. Indeed, feedback has been

glowing. The VRE was described as ‘An excellent forum for discussion and

debate.’ The joint-seminars praised thus: ‘The audio visual format … was

extremely good and gave the opportunity for more academic (tutorial) input than

a conventional seminar.’ Students were not tardy in identifying the potential

and the advantages presented by inter-site collaboration: ‘This has been a most

stimulating and fascinating module. All the teachers, in Hull and in Norwich,

were amazing and very able at putting across their knowledge and insights. One

felt very privileged and lucky to have access to such an array of knowledge.’

We are proud of these attestations and convinced that the format has genuine

promise. The only negative observations to be made in this year’s feedback was

the complaint that there were not more students involved! That is to say they

want the Virtual Research Community of which they are part to be expanded

numerically. Post-Graduate recruitment in the Arts and Humanities is

straightened in these times of tuition fees, but we intend to bring in a third

party, Warwick, next year. Further partners are envisaged.

- The

feedback from tutors has been similarly enthusiastic. Team teaching across

institutions has been exciting, if challenging experience. Above all, the

technological platforms have enhanced the seminars in ways which coincide with

our pedagogical and methodological convictions: student-led and research-led,

enhanced use of digital resources, combining an interdisciplinary and

contextualist approach to sources and with detailed and rigorous inter-textual

analysis. All these themes, present in the discipline and enhanced by the

technology have also been explored in the context of the Virtual Research

Group.

The Early Modern VRE Research Group

- The

expansion of the project facilitated by British Academy funding has two aims:

the creation of the Virtual Research Community, meeting in regular Access Grid

Seminars and supported by an online Collaborative Environment; and to pursue an

innovative and exciting research agenda. The ‘Early Modern VRE Research Group’

was launched at a face-to-face workshop held at UEA on 11 September 2006.

Participants were introduced to ways in which supporting technology would be

used (monthly Access Grid seminars supported by the Sakai portal); and the

project’s scholarly objectives were discussed and defined (interdisciplinary

collaboration under the working title of ‘Different constructions of the

Commonwealth and polity’). This theme was chosen collectively by the members

of the research group because it was felt that it offered the most fertile

territory for the sort of interdisciplinary collaboration and consideration of

diachronic issues that the technological platform would facilitate. Although

conscious of the potential obstacles (perhaps more cultural than technological)

to certain forms of collaboration, participants – many of whom were hitherto

little aware of VRE technologies – expressed resounding enthusiasm for

exploring the transformative potential of technologically enhanced

collaboration for Arts and Humanities research. The group we have assembled is

composed of leading scholars in the field and, for the purposes of

disseminating the potential of this technology, usefully distributed across a

range of institutions around the UK.[16]

- The

participants bring a diversity of approaches to the early modern period (their

disciplines ranging from political science, history of political thought,

history of political discourse, social and cultural history, and English

literature) and, geographically, their interests cover at least Great Britain,

North America and France. This diversity is core to the project’s research

objectives: the VRE technology at our disposal allows research collaboration

to be sustained at a previously unimaginable intensity; the project is

motivated by the belief that this will have a transformative impact upon the

nature of research and research outputs, and that this will be even more

dramatically the case when the different approaches represented in our group

collide on a regular basis.

- In

the present project, we aim to enhance historical understanding of a number of

key terms and concepts (currently Commonwealth, Republic and their associated

networks of value-laden words) by pooling the expertise of scholars across

disciplines and across time. Each scholar brings to the table her or his

distinctive disciplinary approach, guiding questions, means of analysis and

source materials. Integral to this approach is a collective analysis of

conceptual innovation and linguistic change, an exploration of the processes of

conceptual redefinition and a reflection on the methodologies required

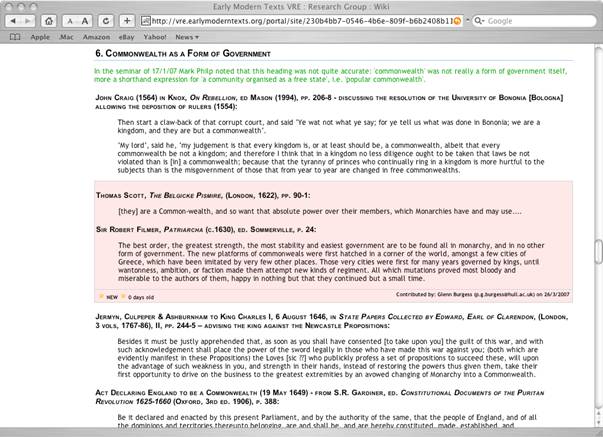

of such exploration. ‘Virtual’ research seminars have been held on a monthly basis

since November 2006, and each has generally involved 12-15 of the 22 project

participants at 8-10 sites. Those unable to attend particular meetings can

listen to recordings of them and read documentation via the VRE site. This

represents a dramatic improvement on what an equivalent research group could

hope to achieve by using conventional transport to overcome distance! We have

purchased 10 Desktop Access Grid licenses allowing more flexible participation,

not governed by room availability, and holding out the possibility of smaller

ad hoc working groups. What is more, our March seminar featured the

transatlantic participation of Professor Michael Winship, University of

Georgia, in a seminar devoted to republicanism in seventeenth century North America.

The potential for this and similar groups to expand internationally is

self-evident and would seem to depend only on the expanding availability of the

technology.

Fig 3: Our third Virtual Research Group Seminar: discussing Professor Glenn Burgess’s paper on ‘Commonwealth’

- Participants

have used the online collaborative environment to share papers, recommended

reading etc prior to seminars; and to exchange comments, discussion

afterwards. Above all, use has been made of the Wiki: a set of easily expandable

web pages which to which all members of the Research Group can contribute.

- Here

interesting human factors have been observed. A dynamic tension exists within

the subject. On the one hand our participants are eager to collaborate and to

exploit to the full the potential for intense, sustained debate which the

technological platforms offer. On the other, the scholarly culture largely

eschews collaborative authorship and traditionally asserts a strong sense

individual ownership of academic work. Analogous opportunities and challenges

have been thrust upon the scholarly historical community by the ‘open-source

research model’ and the ‘wiki way’, as analysed by Roy Rozenzweig.[17]

As correctly identified in that article, the most significant obstacles to

scholarly collaboration are social, to do with the ingrained ‘possessive

individualism’ which characterises much historical practice. On the one hand,

such attitudes seem to be encouraged by the UK’s Research Assessment Exercise.

On the other, as our experience with the VRE Research Group seems to show,

early modern scholars do subscribe, to a large extent, to Merton’s ‘communism of the

scientific ethos’.[18]

It is too early to say exactly what sort of model for publication we will

finally adopt. Attribution and intellectual recognition are clearly

important. But the Research Group’s participants have expressed a strong

commitment to collaboration, to the exchange of ideas and even appropriate

forms of joint ownership of outputs. As participants share ideas, sources,

references and so on in the VRE, we

have developed a useful function for the Sakai wiki which allows participants

to mark their contribution.

Fig 4: Contribution Macro

- Some

seminars have been audio recorded, and when possible these have been made

available as podcasts through the online VRE (rather as it is possible to

‘listen again’ to BBC Radio 4’s programmes via the web). An Access Grid

technology called Memetic[19]

has also been used to create annotated audio-visual recordings of most seminars:

unfortunately, the current state of technology only allows re-use within an

Access Grid room, but it is an area of development which we are tracking.

The VRG’s Research Agenda

- As

indicated above, a substantial ingredient in the Early Modern VRE Research

Group’s innovation is to encourage and facilitate collaboration between

scholars representing different historical sub-disciplines, and other cognate

disciplines, applying diverse approaches and examining disparate sources and

evidence. Examining a key term such as Commonwealth, the group brings together

scholarly insight into the discourse used by different social groups, through a

variety of media, over a period of three and half centuries, in Great Britain,

France and North America. The Research Group’s aim is to take the matter

considerably further: the potential for dramatic innovation, we posit, lies in

the means for sustained collaboration which the technological platforms allow.

- At the time of writing, five AG Seminars have been held for the Early Modern VRE Research Group:

1. Introduction: history of concepts - 15 November 2006

2. Honesty/honestas; words and concepts - 12 December 2006

3. Commonwealth - 17 January 2007

4. Republicanism; Commonwealth in 1649 - 14 February 2007

5. Republicanism in North America - 14 March 2007 - In

forthcoming seminars we will examine the concepts of ‘Res Publica and

République in a French context’ and ‘Plebeian views of the Commonwealth’.

Discussion papers have been shared before seminars by means of the VRE-Wiki;

many contributions have relied heavily upon texts made available through EEBO.

Already this constitutes a bank of material – citations, commentaries,

interpretative and methodological observations – which is being expanded and

refined. The Group has considered methodological issues and analysed key

substantive terms. The following are some of the questions we have been asking.

- What

should be the focus of a historian of political discourse seeking to understand

conceptual innovation and linguistic change (and how are these two related)?

How can we bring together different understandings of the polity held by those

at different social levels? Do they share common languages and concepts? Are we

concerned with words, networks of words, or concepts and how do we define

these? Or, in a move which has proved useful for the present group, should we

be considering ‘summation terms’, reflexive concepts used by societies to

encapsulate their mode of political life or identity? If we accept that the

groupings Commonwealth/Common Weale/Public Weal, res publica/Republic – and

related term, Commonalty – are best understood as summation terms, we must also

ask how change comes about in the meanings of such emblematic concepts. How do

the different strands of discourse, synchronically present in any society,

relate to each other? What, if any, is the interplay between elite and

vernacular discourse, between the appropriation of terms and their redefinition

in local (parochial or county) contexts, and as it occurs in national and

international ‘conversations’. To adapt the expression of a recent

contribution to the VRE-Wiki before the fifth virtual seminar: ‘How do we

relate occurrences in these [various] contexts to the transformation of

concepts and ‘summation terms’?’ And how does the network of discourses relate

to the dramatic, diachronic moments of contestation that punctuate the history

of summation terms?

- The

Group is conscious of the challenges to be confronted by raising such

questions, and of the difficulty of distilling coherence and synthesis from the

ferment of debate. The group’s collaboration through AG seminars and the

VRE-Wiki over the next five or six months, down to our next face-to-face

meeting in September, are focused towards this end. Such collaboration is

indeed part of our experiment. We are interested to learn how scholars react

when confronted by different evidence-sets, variant modes of argumentation,

sub-disciplinary assumptions; how readily they will work together (rather than

alone or in very small groups, which is the norm for most research in the

humanities) and how the technology can help achieve more intense and sustained

collaboration, so as to arrive and a richer and more satisfactory synthesis.

- Preliminary

answers to the questions we have been asking will be offered by the project’s

two published outputs:

- a collaboratively written article on substantive issues (in likelihood an analysis of the related summation terms, Commonwealth, Common Weale, Commonalty; Republic and res publica);

- another

outlining methodological issues encountered through the group’s work and its

examination of the interface between discourse and practice.

- As

noted above, the current research group is explicitly a pilot for a larger

project – for which we hope to receive further funding – An Online Dictionary

of Early Modern Keywords and Concepts. The primary focus is on the

construction of a series of on-line ‘articles’ (together constituting a

‘dictionary’) of keywords in early modern English political and social

vocabulary. These entries will be composed – with appropriate forms of

collaboration – in the VRE-Wiki. They can then be made publicly accessible via

the web. The approach will focus on exploring ‘families’ or clusters of words

to provide both focus and limits to the project. It is particularly important

to de-limit the material in such a way that after three years the outcomes will

be self-sufficient and coherent, yet can also serve as a base for a further

expansion of the project, funding permitting. The ‘families’ of words will

include at least:

- the terminology of ‘commonwealth’, including political organisation (commonwealth, body politic, civil society, state); status (citizen, subject, freeman, bondsman)

- core antonyms: liberty/slavery; vice/virtue; obedience/disobedience

- vocabulary of social description - terms relating to poverty and vagrancy; the language of ‘sorts’; nobility and its varieties

- terms relating to religious belief and practice and its political implications (e.g. tolerance, toleration, persecution, charity, superstition/superstitious, conscience)

- the language of corruption and reform/reformation

- the terms and concepts used about images (icon, idol, representation)

- the lexicon of rhetoric, conversation, discourse, libel and slander

- the metaphorical language of the body and gender

- custom (time out of mind, ancient constitution, memory, privilege, right)

- the concept and words associated with violence

- interest (benefit, gain, profit, advantage, self-interest, private interest)

- loyalty and love: allegiance, friendship, disloyalty, betrayal, fickleness

- words associated with genres (declaration, petition, remonstrance, address, association)

- words associated with moral attributes or failings (ambition, honour, pride, lust, will, hypocrisy)

- the

lexicon of seditious words

- The

Early Modern VRE Research Group and the proposed Online Dictionary of Keywords

present one model of collaboration using emergent technologies. The protocols

for collaboration, (possibly fine-grained) attribution, web-publication and

access are yet fully to be determined; they form interesting, relatively

uncharted territories. The model, however, is clear: it puts eScience

technologies and VRE-Wiki collaboration tools at the disposal of a large, but

relatively circumscribed research group. Other scoping activities we have

conducted sought to identify the desiderata which would allow these initiative

to expand and offer the ‘wiki way’ to larger scholarly community.

Early modern Text forum

- The

third strand of activity we have called the Early Modern Text Forum: this is an

aspirational, blue skies strand to the project. Our vision is of a

collaborative environment providing a forum for a large number of related

research projects. We envisage an umbrella for a series of projects expanding

from the Research Group already established. Collectively, we hope they will

form a heterogeneous virtual community of interrelated related projects,

workgroups and researchers. And we hope the outputs of this activity will

create a resource which will become an attractive point of reference in

itself. As well as wiki entries on themes related to the study of early-modern

texts and their contexts, providing a scholarly forum for debate on issues of

authorship, publication, reception, translation, ‘reading’ etc, we envisage,

for example, annotations and collaborative scholarly ‘editions’ of PDF files or

images such as those available through EEBO. We aspire to an academic wiki,

but not wikipedia: as far as possible open to the academic and student

community but ultimately confirming to quality protocols, requiring editorial

standards, gate-keeping and so on.

- A

second workshop was held at UEA on 12 September 2007. Attended by participants

in the VRE Research Group and by a number of other parties interested in the

use of VREs/eScience to enhance research in the Arts and Humanities, this

workshop had the objective of helping us scope requirements for such a large

scale collaborative research portal. While the first workshop served to launch

what has become an extremely dynamic and promising research group, the second

workshop’s success was of a different order. We presented to participants a

pilot instance of how the Sakai VRE might be used for collaborative research on

early modern texts, to create a community forum which would enhance the use of

resources offered by EEBO and other online databases. Our efforts in preparing

this pilot contributed greatly towards our use of Sakai both for the MA

Programme and for the VRE Research Group. In line with this, the day’s

discussion made it clear that Sakai, with its current level of functionality,

would be well suited to supporting relatively small and tightly-managed

research groups. However, our notion of a large scale portal providing an

umbrella for a number of related projects was found to aspire beyond what Sakai

can currently offer. Two important gaps were identified:

- Resources vs Repository. Sakai’s current resources tool interacts well with the other tools. However, it is, in essence, a manually organised file-structure and as such its coherence would inevitably break down in the context of the sort of large-scale collaborative portal we envisage. More appropriate then, would be the integration of some form of repository allowing content to be retrieved using assorted metadata.

- Annotation. The functionality required to

allow production of collaboratively edited scholarly editions of the sort of

source texts available through EEBO etc. also goes beyond the current

functionality of the Sakai Wiki. More in-depth scoping of these particular

desiderata is required.

- We

hope to be able to extend and expand the project to develop such functionality

and this vision further. In the meantime, we are looking for opportunities to

initiate other research groups using the technology, and which, if appropriate

may contribute to a future Early Modern Texts Forum. We hope that initiatives

in the history of censorship and indexed works and proposed collaborations with

corpus linguists will bear fruit.

Conclusion

- The activities of the VRE for the History of Political Discourse project shows the potential for VREs to enhance pedagogy and research in the Arts and Humanities generally and specifically in Early Modern Studies. In our view the application of eScience collaborative technologies and VREs is an appropriate and timely way of enhancing widely used digital resources. Above all, the focus of this project has been upon encouraging collaboration – among post-graduate in research-led learning, between faculty in inter-site pedagogy, among established researchers exploring the potential of eScience and online technologies. And it does so with the view that research collaboration is called for by current methodological developments in the history of political discourse and in early modern studies generally. Such activities, moreover, are an inevitable and appropriate response to the opportunities opened by digital resources such as EEBO.

What does a VRE for the Arts and Humanities, and more specifically for the History of Political discourse look like? What tools must it comprise and what processes must it support? The RePAH (Research Portals in the Arts and Humanities) report run by Professor Mark Greengrass, University of Sheffield, included among its recommendations a description of the potential it discerned in ‘Managed Research Environments’, which, among other things would give historians easy access to the sort of research tools which have the potential to transform their research (including the sort of easily customizable workflow management tools, resource discovery tools on which historians must increasingly rely).[5] In the results of RePAH and elsewhere, there is also a strong feeling that many aspects of contemporary historical research must benefit from the wider adoption, implementation and development of eScience techniques. Recent scoping surveys in the Arts and Humanities in general and the History subject area in particular have in various ways emphasized the importance and potential for connecting, i.e.:A VRE is a set of online tools, systems and processes interoperating to facilitate or enhance the research process within and without institutional boundaries. The purpose of a Virtual Research Environment (VRE) is to provide researchers with the tools and services they need to do research of any type as efficiently and effectively as possible. This means VREs will help individual researchers manage the increasingly complex range of tasks involved in doing research. In addition they will facilitate collaboration among communities of researchers, often across disciplinary and national boundaries.[4]