The Theory and Practice of Lexicons of Early Modern English

Ian Lancashire

University of Toronto

Ian Lancashire. "The Theory and Practice of Lexicons of Early Modern English." Early Modern Literary Studies 14.2/Special Issue 17 (September, 2008) 5.1-25 <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/14-2/Lanctheo.html>.

Introduction

- The University of Toronto Press and the University of Toronto Library jointly launched my Lexicons of Early Modern English (LEME)

on April 12, 2006. LEME offers both free, public access to and a

licensed scholarly site for half a million word-entries in more than 155

lexical works, print and manuscript, written by English speakers from about

1480 to 1702. Growing year by year, it documents, analytically, what those

alive in this long period thought that words meant. Because we can only

understand a language partially and locally—its words tend to be the product of

a place, a date, a social community, and even a person—LEME builds on

whatever surviving documents that describe words. LEME does not make its

own definitions. In deciding word-meaning, contemporary authors have an

authority above those of us who live centuries later. People do not have to be

great writers or lexicographers to share this authority. It is just enough that

they spoke the language and made observations about the English words they

used.

- There are three ways to find

words in LEME: typing in a query string; and browsing either a

comprehensive alphabetical word-list, or a table of editorially normalized

headwords from LEME word-entries. LEME word-or-string searches

retrieve individual word-entries, sometimes with a link to the EEBO image

(which usefully grounds LEME transcriptions in facsimiles of its single

documents). LEME can also restrict queries by language, date, title,

author, genre, and subject. Each set of results graphs the distribution of the

word over two centuries. Or the researcher can approach the collected

word-horde through the full LEME alphabetical word-list: it enables a

researcher to browse every word-form in the transcribed lexical works and call

up each word-entry in which the queried word-form is found. This word-list

parallels the Early English Books Online/Text Creation Partnership (EEBO/TCP)

master word-list. A third option, intended for researchers who want

old-spelling occurrences of words collected under one modern-spelling headword,

is to use the modernized, editorially-lemmatized headwords list. A lemma—on

which the name LEME quibbles—is an inflectionally-related group of

words. For example, the lemma for old spellings like "gives",

"giues", and "giueth", and inflectional variants like

"giue", "giuing", "gaue", "giues", and

"given", is the general infinitive form, "give." Normally, LEME

lemmas are editorially standardized on Oxford English Dictionary headwords.

Revising the Early Modern English Lexicon

- LEME indexes bibliographically some 1,200

lexical works from about 1480 to 1702. My major sources for printed texts are

Robin Alston's in-progress bibliography, EEBO, and pioneering scholarship by

Gabriele Stein and others. The comprehensiveness of LEME's index of

lexicons distinguishes it from its sources: it lists all kinds of lexical

works, whether bilingual or monolingual, by author, date, title, subject, and

genre. It includes manuscript lexical works as well as small glossaries within

treatises. The large secondary bibliography that annotates this index—again, a

resource not available elsewhere—adds other overlooked primary works to this

bibliography. For example, last fall, with the help of a British Library

reference librarian I found—and notified EEBO, which now includes it—what seems

to be the first Renaissance English bilingual glossary to be printed, the

anonymous Floures of Ouid in 1513. This gives balanced English-Latin and

Latin-English glossaries for grammar-school students and serves their study of

sentences from Ovid's Art of Love. For example, last fall, with the help

of a British Library reference librarian I found—and notified EEBO, which now

includes it—what seems to be the first Renaissance English bilingual glossary

to be printed, the anonymous Floures of Ouid in 1513. This gives

balanced English-Latin and Latin-English glossaries for grammar-school students

and serves their study of sentences from Ovid's Art of Love.

- University of Toronto membership in EEBO/TCP helped me to locate texts that explain Early Modern English

terminology. Frederick Furnivall founded the Early English Text Society (EETS)

to assist Oxford English Dictionary lexicographers to find words and citations

for them in hitherto unedited texts. EEBO/TCP is both the new OED's and LEME's

digital EETS. The EEBO/TCP master word-list, when searched for terms like

"glossary," "vocabulary," "definition,"

"dictionary," and "lexicon," identifies otherwise elusive

lexical commentaries, tables, and pockets of word-explanations that translators

and treatise-writers bundled with their works. EEBO/TCP also gives LEME valuable

digital transcriptions for several lexicons, especially Thomas Wilson's Christian

Dictionary (1612), Edward Phillip's World of Words (1658), William

Lloyd's dictionary of the semantic analyses of words in Bishop Wilkin's Essay

(1668), and Elisha Coles' English Dictionary (1676). These added

significantly to the total word-entries in LEME. Perhaps there are more

helpful projects in research infrastructure for the Early Modern English period

than EEBO/TCP, but I do not know what they are.

- How, then, does LEME differ

from a collection like EEBO/TCP? LEME has proofread texts and emended

erroneous readings. Its database implementation allows for selective retrieval

of words by language, position (headword, explanation), and lemma, gives a

detailed profile of the vocabulary of the period, decade by decade, offers

ready access to all period lexical works at once, and represents a start on the

yet unrealized period dictionary of Early Modern English (Bailey 1985), the

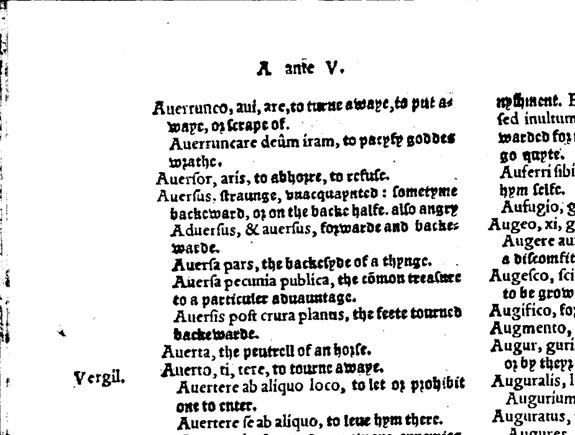

successor to the Middle English Dictionary. A comparison of the original image

of Sir Thomas Elyot's Bibliotheca Eliotae (1542), an EEBO/TCP

transcription of part of its text, and the LEME parallel transcription

will show some of these differences.

<p><em>Auersus.</em> straunge, vnacquaynted: sometyme backeward,

or on the backe halfe. also angry <em>Aduersus, &

auersus,</em> forwarde and backewarde.</p>

<p><em>Auersa pars,</em> the backesyde of a thynge.</p>

<p><em>Auersa pecunia publica,</em> the co~mon treasure to a

particuler aduauntage.</p>

<p><em>Auersis post crura planus,</em> the feete tourned

backewarde.</p> - EEBO/TCP distinguishes Latin headwords from

English translations or equivalents by the use of emphasis tags, but it also removes

the distinction between a main word-entry such as "Auersus" and its sub-entries

(e.g., "auersa pars"). Lost is the indenting by which Elyot

subordinates sub-entries under main entries. LEME adds the encoding of these

semantic hierarchies (in which sub-entries fall under main entries) manually.

<wordentry><form>Auersus.</form> <xpln lexeme="strange(a)" lexeme="unacquainted(a)" lexeme="backward(a)" lexeme="back half, on the(adv)" lexeme="angry(a)" lexeme="forward and backward(adv)" lexeme="backside(n)" lexeme="treasure, common(n)" lexeme="feet, turned backward(a)">straunge, vnacquaynted : sometyme backeward, or on the backe halfe. also angry

<term lang="la">Aduersus, & auersus,</term> forwarde and backe­

warde.

<subform>Auersa pars,</subform> <subxpln>the backesyde of a thynge.</subxpln>

<subform>Auersa pecunia publica,</subform> <subxpln>the c<expan type="+_">om</expan>mon treasure

to a particuler aduauntage.</subxpln>

<subform>Auersis post crura planus,</subform> <subxpln>the feete tournedbackewarde.</subxpln></xpln></wordentry> - LEME also

adds lemmatized word-forms for all English equivalents within "lexeme"

attributes in the so-called <xpln> (explanation) tag. At present our

semi-automatic lemmatization software functions reasonably well for between 84%

and 98% of English terms, depending on the lexicon. The remainder of

lemmatizations have to be done manually.

- This extra encoding is

labour-intensive but, in the long run, valuable. Manual grouping of sub-entries

under main entries offers a wider context for understanding why, for instance,

a Latin phrase for a form of torture (turning the feet around backwards)

belongs under "Auersus": one of the translations of the headword is

"angry." Lemmatization has other advantages. It enables users to

retrieve all forms of the same word, whether different spellings (like

"backeward" and "backewarde") or different inflections of

verbs (like "tourned" and, say, "tourne"), at the same

time. As important, once all orthographic forms of a word can be associated

with its OED headword, LEME can measure, over this period, when words

first were recognized as English. In this way we can determine the rate at the

national lexicon expanded.

Supplementing the Oxford English Dictionary

- The OED takes 25,324 quotations from the works of Shakespeare, whose

authoritative concordance has just over 29,000 headwords (which include plenty

of duplicate entries, because alternate spellings, inflectional variants, and

emended word-forms are given separate headwords). It would probably be fair to

say that OED quotes almost every word-type that Shakespeare used. Jürgen

Schäfer (1980) shows how this over-represents Shakespeare's lexical

inventiveness. Compare the above numbers with the OED coverage of Renaissance

lexicons that serve English. The OED takes 17,624 quotations from fifty-two

sizable British dictionaries found in LEME, most of them printed, from

1499 to 1623 (see Table 1), but these lexical works have a total of 412,847

word-entries, the majority of which illustrate more than one English word. The

OED draws citations from only 4.3 percent of word-entries in these lexical works.[1]

- LEME significantly supplements the OED,

documenting new words and senses, antedating first-usage information, and

delineating Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish words that were thought to

correspond to English words. The sheer scale of the data that a LEME

query retrieves shows minute changes in language usage over time. For example, LEME

can sometimes tell us when a word drops out of favour, and when a new loan-word

fails to establish itself. Although OED remains an unrivaled authority for

etymology, inflectional history, and language usage by non-lexicographer

authors—it truly describes "the meaning of everything"—in matters

Early Modern its selection of quotations is biased towards one playwright, and

against harder-to-locate works that express how the period documented its own

tongue. The OED also occasionally observes a theory of language that reflects

late Victorian and early twentieth-century thinking—for instance, that words

signify mental ideas—rather than Early Modern beliefs, which take nouns as

names for things.

- Fifteen years ago, when

developing the Early Modern English Dictionaries Database (EMEDD) that preceded

LEME, I used these lexical works to re-annotate passages from

Shakespeare in the hope of showing how revisionist the use of contemporary

lexical sources was in scholarly editing and close reading. My finding that

Shakespeare's first villain, Aron in Titus Andronicus, took his name

from a common English weed, priest's pintle, aron, wake robin, or ramp, rather

than from Moses' brother Aaron, was persuasive for some (1997). No matter the

Early Modern text, however, using LEME brings out surprising senses and

nuances (Lancashire 1993, 2003).

- Let me illustrate this again with

two words, "dodkin" and "personate", from a sentence chosen

entirely at random from the EEBO/TCP transcript of Thomas Nashe's Strange

News (1592):

Trust mee not for a dodkin, if there bee not all the Doctourship hee hath, yet will the insolent inke-horne worme write himselfe Right worshipfull of the Lawes, and personate this man and that man, calling him my good friend Maister Doctour at euery word. (d4r)

- A LEME search for "dodkin"

delivers nineteen word-entries from 1570 to 1676 devised by ten glossographers

from Peter Levins (1570) to Elisha Coles (1676). They give somewhat different

information to what appears in the OED entry for "dodkin", which has

two senses, the small-value Dutch coin named a doit, and a bud or pistil. John

Cowell (1607), Thomas Blount (who copies him; 1656), and Edward Phillips (who

copies Blount; 1658) all support the OED reference to a coin, associating it

with the French shilling. In two earlier word-entries, however, John Baret

(1574) has a different gloss: first, "a Dandeprat: or dodkin" as "Hilum, li, n.ge.

Teruncius, tij m.g. A knaue scante worth a dandeprat. Trioboli, vel triobolaris

homo. Plaut"; and, secondly, "a Dodkin" as "of small value: a thing of naught. Hilum,

li, n.g. Cic. Teruntius, tij, m.g. Cic. Vng quadrin, vn liard. He has not sent

a Dodkin, or one farding. Ne teruntium quidem misit Eras." Randle Cotgrave

(1611) echoes Baret's gloss in illustrating the French word "Zest":

"Il ne vaut pas vn Zest. He is not worth a dodkin,

straw, rush, a pinnes head, the taking vp." Nashe thus uses the senses

that Baret and Cotgrave document rather than ones found in the OED.

- The LEME modern headwords

word-list gives the word "personate" in six lexicons, five hard-word

tables by Robert Cawdrey (1604), John Bullokar (1616), Henry Cockeram (1623),

Thomas Blount (1623), and Edward Phillips (1568), and a general dictionary of

the entire language by John Kersey (1702). Their dominant sense is "to

counterfeit, represent, resemble, or act" another person, but Blount and

Phillips add another meaning, "to sound out … or make a great noise."

Again, the OED and these lexicons have somewhat different senses. Both document

the main sense, "to represent," but LEME also has evidence for

a minor one, "sound out."

- This little exercise shows that Early

English vocabulary splits into two, mother-tongue words on the one hand, and

loan-words or terms of art, on the other hand. The word "dodkin"

appears in bilingual lexicons (Baret, Cotgrave) as an insult, a sign of belonging

to the mother tongue, as well as in hard-word tables (Blount, Phillips, and

Coles), a sign of its foreign extraction from Dutch. In contrast,

"personate" occurs uniformly in hard-word lexicons: it is a

neologism, a loan-word from Latin. LEME results also supplement the OED

with novel information about senses. Only Blount documents a sense,

"sound out" (for "personate"). Phillips plagiarized this

from him, and then the sense exited the language.

Revising Language History

- A creature of postmodernism, LEME affects

our understanding of the history of the English language. Using it introduces

interpretive doubts by giving readers so much information that their assured

certainties about what even common words meant fall away. Yet it is also

faithful to its period, when language grew without controls, giving linguistic

opportunities to the adventurous, confusing readers and listeners who were

lobbied to learn languages like Latin, French, and Italian and who had few

resources to learn or maintain their own mother tongue, English. Until 1623, the

English language had no general dictionary of English hard words, and until

much later, with the work of John Kersey (1706), no comprehensive lexicon of

both hard words and the mother tongue. LEME supplies what would have

been useful in Shakespeare's London: a guide to how the mother tongue squared

itself against a polyglot insurgence from within.

- R. F. Jones believed that the late sixteenth century marked

"the triumph of English," but if there was any victory, it took place

much later. It is well known how uneven was the teaching of English in the

early Tudor period. People educated their male children to speak that great

Renaissance interlingua, Latin, in grammar schools like Magdalen College, Oxford, that refused students permission to use their mother tongue: Latin was the

rule for them at all times. One student says, in a late fifteenth-century

collection of passages for Latin translation: "Iff I hade not usede my

englysh tongue so greatly, the which the maistre hath rebukede me ofte tymes, I

shulde have ben fare more lighter (or, conyng) in grammer. wis men saye that nothyng

may be more profitable to them that lurns grammer than to speke latyn"

(Nelson 1956: 22). To foreigners like Erasmus, Tudor English sounded like dogs

barking, so many were its monosyllabic Saxon words (Giese 1937). If Erasmus did

not bother to learn English when he lived in the country for some years, what

could be expected of foreigners? John Florio's first dialogues for the teaching

of Italian, in 1578, confirmed that little had changed since Erasmus' time.

Visiting foreigners thought English "woorth nothing" beyond Dover:

it is a language confused, bepeesed with many tongues: it taketh many words of the latine, & mo from the French, & mo from the Italian, & many mo from the Duitch, some also from the Greeke, & from the Britaine, so that if euery language had his owne wordes againe, there woulde but a fewe remaine for English men, and yet euery day they adde. (n2v)

To judge from the anonymous English-Latin Promptorium Parvulorum (1499), John Palsgrave's English-French Lesclarcissement (1530; two large bilingual works), and William Tyndale's popular translation of the New Testament (1525), which he wrote with "a boye that dryueth the plough" in mind, it had only about 20,000 words in circulation in the reigns of the early Tudors.

- As John Florio notes, Early Modern English lexicons tell

us that native speakers in Renaissance England believed that their vocabulary

extended along a lexical spectrum from common, spoken words (the mother tongue)

to technical trade words (terms of art) and words borrowed from other languages

(so-called hard words). Over two hundred years, as new knowledge and

technologies introduced concepts for which no ready vernacular term existed,

English became engorged with new words (McConchie 1997; Nevalainen 1999;

McDermott 2002), especially from Latin and French, even as basic everyday

English, until the late sixteenth century, appears to have been untaught except

for its spelling. By about 1525, publishers had introduced the first

stand-alone encyclopedic lexicons to explain professional vocabularies (law and

herbs) and the first in-text hard-word glossaries (Hüllen 1999). These

explicated neologisms that were usually coined, on-the-spot, by translators who

either could not find native equivalents or wanted their writing to sound authoritative

and impressive. Jürgen Schäfer first showed (1989: I, 8) how, after

three-quarters of a century, the quantity of hard words introduced by

individual translators increased to the point that publishers could sell

stand-alone lexicons of hard words for all subjects.

- These hard-word lexicons grew in size from about 1,700

words in Edmund Coote's glossary (1596) to 28,000 words in

late-seventeenth-century "English" dictionaries by Thomas Blount,

Edward Phillips, and Elisha Coles. Robert Cawdrey, author of the first

stand-alone English hard-word lexicon, Table Alphabeticall (1604),

relied heavily on Thomas Thomas's Latin-English dictionary (1587) but only

glossed "Hard Vsual English Words", a limitation that excluded

objectionable inkhorn terms. Other larger hard-word dictionaries followed: John

Bullokar (1616), Henry Cockeram (1623), Thomas Blount (1656), Edward Phillips

(1658), and Elisha Coles (1676). By the 1640s, even a man as well-educated as

Sir Thomas Blount confessed himself "gravell'd" in his reading, that

is, stuck when he came upon a novel English word he did not know and could not

interpret. Anyone who has suffered from kidney stones will know how Blount

felt. The Renaissance transformed English gradually into a multilingual Babel,

the ancient language of monosyllabic and disyllabic words taught by mothers,

and a new hard-word, term-of-art, often polysyllabic vocabulary, sufficiently

omnipresent to remind one of a third linguistic invasion, not by Saxons after

the sixth century or by Normans after 1066 but by publishers and their hungry,

neologizing and translating authors. By the early eighteenth century, Nathan

Bailey gradually dominated the English dictionary market by collecting more

hard words than anyone else, up to 60,000. However, it was Samuel Johnson who

secured Jones' "triumph of English" when he met Robert Dodsley's

challenge to produce the first great dictionary of core English in mid-century

in 1755. His work offered a modest 40,000 word-entries.

- LEME shows how those living in the Renaissance

regarded English and its two tongues, basic and hard-word, as maturing,

intertwined quasi-polyglot languages. Lexicon entries for words such as

"dictionary" reveal how self-conscious were lexicographers in this.

William Mulcaster (1582) says that hard words earned their place in mother

English by being enfranchised, that is, given citizenship. He recognizes two word-streams,

one adopted by its native land, and the other countryless and unauthorized.

Randle Cotgrave in his French-English dictionary (1611) iterates this in

translating the French word "Espave" as "Maisterlesse; without

author, or owner; also, forreine, farre-borne; of vnknowne birth, or beginning.

Mots espaves. Strange, new-forged, vnaccustomed, words." John Florio

lacked even the concept of a "monolingual dictionary" in 1598,

titling his Italian-English lexicon a "world of words." John Kersey's

surprising word entry in 1702, "A Glossary, or dictionary, explaining divers

languages" (my italics; 1702), confirms Mulcaster and Cotgrave.

Renaissance dictionaries in England served two or more tongues.

- Paradoxically, LEME shows that Early Modern

English-first bilingual dictionaries, glossaries, and vulgaria are, outside

Bible translations (which offer only small glossaries, mostly of proper names),

the best guides to the mother tongue. Bilingual lexicons had to employ common

English words as equivalents if they were to make foreign terminology

understandable. Those with a native-to-foreign directionality, that is, those

with English headwords, and foreign-language equivalents in the post-lemmatic

position, served to translate their common words into other languages. When no

English term was available, the lexicographer would use a phrasal headword.

John Withals' popular English-Latin dictionary (1556) shows that English did

not yet possess the words "posthumous" and "abortion": he had

to use the roundabout sentences, "He that is borne after that his father

is deade" and "childe borne afore his time", to translate the

Latin equivalents. English-first bilingual lexicons by such as Withals slowed

the inroads made by loan-words, as did hard-word and terms-of-art

lexicographers. A mid-century spate of English-Latin dictionaries by Richard

Huloet (1552), Withals, Peter Levins (1570), John Baret (1574), and John Rider

(1589) put English first. They were followed, however, by huge bilingual

dictionaries with a foreign-to-English directionality, that is, those with

foreign-language headwords and English equivalents in the post-lemmatic

position, and they promoted neologizing. Great, often reprinted bilingual

lexicons—Sir Thomas Elyot (1538-48), Thomas Cooper (1565-84), and Thomas Thomas

(Latin, 1538-87), Richard Percival and John Minsheu (Spanish, 1591, 1599,

1617), John Florio (Italian, 1598, 1611), and Randle Cotgrave (French, 1611)—conferred

authority on the headword's foreign language, not on English, a directionality

that accelerated borrowing.

- These varied lexicons balanced

two needs, the expansion of English into a world language, and its standardization

as a native language. Lexicographical self-regulation simultaneously accelerated

and braked the growth of English. A LEME query can determine into which

language, the mother tongue or the new hard-word vocabulary, a term falls by

searching for it separately in multilingual texts first, and second in

monolingual English texts. If a term occurs most frequently in multilingual

lexicons, it very likely belongs to the mother tongue, no matter its etymology.

Conclusion

- LEME first came about because I realized

that the directionality of bilingual lexicons that placed their

all-but-inaccessible (to a facsimile reader) English equivalents in

post-lemmatic explanations could be reversed once these lexicons were digitized.

A lexicon alphabetized by Latin headwords could be read as if it was alphabetized

by English headwords. Once all lexicons of whatever directionality had been

digitized and conflated, it seemed to me, we would have a very large virtual

Early Modern English dictionary, one written entirely by lexicographers of the

period. This mega-lexicon would even look like a historical period

dictionary insofar as it consisted of quotations from works of the time. Because

only four percent of these citations are found in the OED, we stand to gain a new

understanding of much Early Modern English vocabulary if this mega-dictionary is

made accessible to everyone online. Gradually, in collecting lexicons for

data-entry, I saw that they suggested a stranger-than-expected contemporary

understanding of Early Modern English (cf. Anderson 1996). Early Modern English

lexicographers interpreted words as signs more for things (Lancashire 2003)

than for ideas, and the boundary between a lexicon and an encyclopedia broke

down. Second, the different distributions of vocabulary into bilingual and

monolingual hard-word lexicons suggested that English had divided into two

tongues. Third, the high demand for bilingual dictionaries, and the low demand

for English-only lexicons, hinted that English had become, in effect, polyglot.

- James Howell, in his Tetraglotton (1660),

asserted the emergence of English as a European tongue by producing a polyglot

lexicon of four languages, English, French, Italian, and Spanish. His

frontispiece engraving, "Associatio Linguarum" (prominently displayed

on the main LEME page), emblematizes the inextricability of English and

its sister languages. Three of the four mother tongues take the arm of English

in a picture that supports Howell's main contentions: that English is a major

European language and that it owes many of its words to these three sisters

and their mother, Latin. This frontispiece symbolizes the findings of LEME.

- How are we to disseminate this lexical information to

researchers whose use of dictionaries is so infrequent? Convenience is an

important factor: anyone, anywhere, whether or not they have licensed the full

version of LEME, should be able to cite and call up any of its word-entries.

For that reason, LEME gives every analyzed word-entry its own URL. An

online scholarly edition of an Early Modern English work can thus freely cite,

in its annotations, any analyzed LEME word-entry. And any reader can freely

call up and verify that entry. Early in the year before I first gave a paper on

the EMEDD—at the third joint conference

of the ACH and ALLC at Tempe, Arizona, in March 1991—Tim

Berners-Lee invented the Uniform Resource Locator. It was thus the most natural

thing in the online world, by 2006, to give each LEME word-entry its

unique URL.

[1] The online second edition of the OED was searched March 18-19, 2007.

References

Anderson, Judith. (1996.) Words that Matter: Linguistic Perception in Renaissance English. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Alston, Robin C. (1965-.) A Bibliography of the English Language from the Invention of Printing to the Year 1800. Bradford, Leeds, Ilkley, and Otley: Ernest Cummins, University of Leeds, E. J. Arnold, Grove Press, and Smith Settle.

Bailey, Richard W. (1985.) "Charles C. Fries and the Early Modern English Dictionary." In Nancy M. Fries, ed. Toward an Understanding of Language: Charles Carpenter Fries in Perspective. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 171-204.

Baret, John. (1574.) An Aluearie or Triple Dictionarie, in Englishe, Latin, and French. London: Henry Denham.

Blount, Thomas. (1656.) Glossographia. London: Thomas Newcomb for Humphrey Moseley and George Sawbridge.

Bullokar, John. (1616.) An English Expositor: teaching the interpretation of the hardest words in our language. London: John Legatt.

Cawdrey, Robert. (1604.) A table alphabeticall, conteyning and teaching the understanding of hard usuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. London: E. Weaver.

Cockeram, Henry. (1623.) English Dictionarie: or, an interpreter of hard English words. London: Eliot's Court Press for N. Butter.

Coles, Elisha. (1674.) The Compleat English Schoolmaster. London: Peter Parker.

—. (1971.) An English Dictionary, 1676. Menston: Scolar Press.

Coote, Edmund. (1596.) The English Schoole-maister. London: Widow Orwin for Ralph Jackson and Robert Dexter.

Cotgrave, Randle. (1611.) A dictionarie of the French and English tongues. London: A. Islip.

Early English Books Online. (2003-). ProQuest Information and Learning Co. URL: http://eebo.chadwyck.com .

Early English Books Online / Text Creation Partnership. 2000-. Ann Arbor, MI. URL: http://www.lib.umich.edu/tcp/eebo/index-2.html .

Early Modern English Dictionaries Database. (1996-99.) Comp. Ian Lancashire. Toronto: CHASS. URL: www.chass.utoronto.ca/english/emed/emedd.html .

Elyot, Sir Thomas. (1538.) The Dictionary of syr Thomas Eliot. London: T. Berthelet.

--. Bibliotheca Eliotae Eliotis librarie. (1542.) London: T. Berthelet.

Florio, John. (1578.) His Firste Fruites. London: Thomas Dawson for Thomas Woodcocke.

—. (1598.) A worlde of wordes, or most copious, dictionarie in Italian and English. London: E. Blount.

—. (1611.) Queen Anna's New World of Words. London: Edward Blount and William Barret.

Giese, Rachel. (1937.) "Erasmus' Knowledge and Estimate of the Vernacular Languages." The Romanic Review 28 (Feb): 3-18.

Howell, James. (1659-60.) Lexicon Tetraglotton, An English-French-Italian-Spanish Dictionary. London: Cornelius Bee, or Samuel Thomson, or Thomas Leach.

Hüllen, Werner. (1999.) English Dictionaries 800-1700: The Topical Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Huloet, Richard. (1970.) Abecedarium Anglico-latinum, 1552. Menston: Scolar Press.

Johnson, Samuel. (1979.) A Dictionary of the English Language. Intro. by Robert W. Burchfield. London: Times Books.

Jones, Richard Foster. (1953.) The Triumph of the English Language: A Survey of Opinions Concerning the Vernacular from the Introduction of Printing to the Restoration. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kersey, John. (1702.) English Dictionary: Or, a Compleat: Collection Of the Most Proper and Significant Words, Commonly used in the Language. London: Henry Bonwicke and Robert Knaplock.

—. (1706.) [Edward Phillips'] The new world of words; or, Universal English dictionary. Containing an account of the original or proper sense, and various significations of all hard words derived from other languages. London: J. Phillips.

Lancashire, Ian. (1993.) “The Early Modern English Renaissance Dictionaries Corpus.” In J. Aarts, P. de Haan, and N. Oostdijk, eds. English Language Corpora. Language and Computers, no. 10. Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi. 11-24.

--. (1994.) "An Early Modern English Dictionaries Corpus 1499-1659." In Ian Lancashire and T. R. Wooldridge, eds. Early Dictionary Databases. CCH Working Papers 4. 75-90.

—. (1997.) “Understanding Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus and the EMEDD.” In New Scholarship from Old Renaissance Dictionaries: Applications of the Early Modern English Dictionaries Database. Ed. Ian Lancashire and Michael Best. A special issue of Early Modern Literary Studies April 1997. URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/emlshome.html .

—. (2002.) `"Dumb Significants’ and Early Modern English definition/" In Jens Brockmeier, Min Wang, and David R. Olson, eds. Literacy, Narrative and Culture. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. 131-54.

—. (2003.) "The Lexicons of Early Modern English." TEXT Technology 12.1. Also at http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/epc/chwp/CHC2003/Lancashire2.htm (CH Working Papers A. 23).

—. (2005.) "Lexicography in the Early Modern English Period: the Manuscript Record." Historical Lexicography. Ed. J. Coleman and A. MacDermott. Tübingen: Max Niermeyer. 19-30.

Levins, Peter. (1570.) Manipulus Vocabulorum. London: by Henrie Bynneman for John Waley.

Lexicons of Early Modern English. (2006.) Ed. Ian Lancashire. Toronto: University of Toronto Press and University of Toronto Library. URL: http://leme.library.utoronto.ca .

McConchie, R. W. (1997.) Lexicography and Physicke: The Record of Sixteenth-century English Medical Terminology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McDermott, Anne. (2002.) "Early Dictionaries of English and Historical Corpora: In Search of Hard Words." In Vera, Javier E. Diaz, ed. A Changing World of Words: Studies in English Historical Lexicography, Lexicology and Semantics. Amsterdam: Rodolpi. 197-227.

Middle English Compendium. (2001.) University of Michigan Digital Library Production Service. URL: http://ets.umdl.umich.edu/m/mec/ .

Minsheu, John. (1599.) A Dictionarie in Spanish and English, first published into the English tongue by Ric. Perciuale. London: Edm. Bollifant.

—. (1617.) Ductor in Linguas. London: John Browne.

Mulcaster, Richard. (1582.) The first part of the elementarie. London: Thomas Vautroullier.

Nashe, Thomas. (1592.) Strange Newes. London: John Danter.

Nelson, William, ed. (1956.) A Fifteenth Century School Book from a Manuscript in the British Museum (MS. Arundel 249). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nevalainen, Terttu. (1999.) "Early Modern English Lexis and Semantics." In Roger Lass, ed. The Cambridge History of the English Language. Volume III: 1476-1776. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ovid. (1513.) The flores of Ouide de arte amandi with theyr englysshe afore them: and two alphabete tablys. London: Wynkyn de Worde.

Palsgrave, John. (1530.) Lesclarcissement de la langue francoyse. London: R. Pynson and J. Haukyns.

Phillips, Edward. (1969.) The New World of English Words, 1658. Menston: Scolar Press.

Promptorium Parvulorum. (1968.) Menston: Scolar Press.

Rider, John. (1589.) Bibliotheca Scholastica. Oxford: Joseph Barnes.

Schäfer, Jürgen. (1980.) Documentation in the O.E.D.: Shakespeare and Nashe as Test Cases. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

—. (1989.) Early Modern English Lexicography. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Stein, Gabriele. (1985.) The English Dictionary before Cawdrey. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Thomas, Thomas. (1587.) Dictionarium Linguae Latinae et Anglicanae. Canterbury: Richard Boyle.

Tyndale, William, trans. ([1525.]) [The New Testament. Cologne.]

Wilkins, John. (1968.) An Essay towards a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language, 1668. Menston: Scolar Press.

Wilson, Thomas. (1612.) A Christian dictionarie. London: William Jaggard.

Withals, John. (1553.) A Shorte Dictionarie for Yonge Begynners. London: T. Berthelet.

-----------------------------

Table 1: LEME Word-entries and OED Citations

| WORK | Date | LEME | OED |

| word-entries | citations | ||

| Promptorium Parvulorum | 1499 | 10510 | 5372 |

| Banckes' herbal | 1525 | 206 | 0 |

| Rastell's Expositions | 1525 | 194 | 0 |

| Hervet's glossary | 1526? | 150 | 0 |

| Brunschwig's Virtuous Book of Distillation | 1527 | 307 | 202 |

| Palsgrave's Lesclarcissement | 1530 | 18864 | 683 |

| Elyot's Dictionary | 1538 | 26560 | 302 |

| de Vigo's Works of Chirurgery | 1543 | 430 | 254 |

| Salesbury's Dictionary in English and Welsh | 1547 | 7016 | 72 |

| Turner's Names of Herbs | 1548 | 426 | 272 |

| Thomas's Principal Rules of the Italian | 1550 | 8255 | 2 |

| Sherrey's Treatise of Schemes and Tropes | 1550 | 147 | 27 |

| Withals' Short Dictionary | 1556 | 4626 | 143 |

| Lanfranco of Milan his Brief | 1565 | 283 | 0 |

| Golding's Caesar | 1565 | 184 | 18 |

| Lily's Short Introduction of Grammar | 1567 | 1062 | 0 |

| Nowell's Vocabularium Saxonicum | ca. 1567 | 7760 | 16 |

| Levens's Manipulus Vocabulorum | 1570 | 8893 | 132 |

| Baret's Alveary or Triple Dictionary | 1574 | 5671 | 308 |

| Kymraeg Sacsonaec | ca. 1575-1600 | 6555 | 0 |

| Banister's Treatise of Chirurgery | 1575 | 560 | 0 |

| Rastell's Exposition | 1579 | 312 | 12 |

| Mulcaster's Elementary | 1582 | 7886 | 2 |

| Batman's Bartholomew | 1582 | 145 | 0 |

| Cooper's Thesaurus | 1584 | 37199 | 686 |

| Thomas's Dictionarium | 1587 | 36626 | 1 |

| del Corro's Spanish Grammar | 1590 | 952 | 0 |

| Stepney's Spanish School-master | 1591 | 1807 | 0 |

| Greaves's Grammatica Anglicana | 1594 | 594 | 0 |

| Minadoi's The History of the Wars | 1595 | 238 | 1 |

| Coote's English School-master | 1596 | 1343 | 6 |

| Speght's Chaucer | 1598 | 2127 | 13 |

| Florio's World of Words | 1598 | 43428 | 290 |

| Gabelhouer's Book of Physic | 1599 | 113 | 119 |

| Minsheu's Dictionary in Spanish | 1599 | 25553 | 179 |

| Livy's Roman History (Holland) | 1600 | 175 | 1192 |

| Pliny's History of the World (Holland) | 1601 | 257 | 2880 |

| Plutarch's Morals (Holland) | 1603 | 344 | 986 |

| Cawdrey's Table Alphabetical | 1604 | 2444 | 226 |

| Bartas' Divine Weeks and Works | 1605 | 637 | 7 |

| Verstegan's Restitution | 1605 | 613 | 183 |

| Cowell's Interpreter | 1607 | 2218 | 109 |

| Cotgrave's Dictionary of the French | 1611 | 47310 | 695 |

| Florio's Queen Anna's New World of Words | 1611 | 70388 | 136 |

| Wilson's Christian Dictionary | 1612 | 3814 | 0 |

| Strachey's Virginia Britannia | 1612 | 972 | 15 |

| Bedwell's Mohammedis Imposturae | 1615 | 162 | 17 |

| Bullokar's English Expositor | 1616 | 4160 | 55 |

| Woodall's Surgeon's Mate | 1617 | 165 | 454 |

| Mainwaring's Nomenclator Navalis | ca. 1620-23 | 530 | 5 |

| Dodderidge's Proper Names | 895 | 0 | |

| Cockeram's English Dictionary | 1623 | 10781 | 1552 |

| 412847 | 17624 | ||