Coriolanus and the Paradox of Place

Doug Eskew

Colorado State University–Pueblo

doug.eskew@colostate-pueblo.edu

Doug Eskew. "Coriolanus and the Paradox of Place". Early Modern Literary Studies 15.1 (2009-10) <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/15-1/eskecori.html>.

- To describe the place of Shakespeare's stage as one of simultaneity is nothing new. Sir Philip Sidney in his Defence famously inveighed against the simultaneity of place in stage plays having "Asia of the one side, and Afric of the other, and so many other under-kingdoms" (45). Just as famously, the Chorus to Shakespeare's Henry V celebrates, if apologetically, how the singular place of the platform stage might represent places innumerable; in his words, "a crooked figure may / Attest in little place a million" (Prologue 11-12).1 Another kind of simultaneity can be seen in the way Shakespeare and his fellow dramatists often placed their dramas abroad, but meant for them to stand for locations in England--often as a kind of "plausible deniability" or topographical euphemism that allowed playwrights to criticize English authority from a safe distance.2 Douglas Bruster describes this "refusal to stay abroad" of English drama as "anatopism," a term that "recognize[s] the ultimate slipperiness of settings and locales" (33) in Renaissance drama. Leah Marcus attributes this mobility of place to the "Renaissance penchant for topical speculation" and notes that "Place in Shakespeare is more highly charged, more elusive, sometimes more downright deceptive than the reassuring advance labels provided by modern editors allow us to perceive" (161).3

- This essay deals with the "elusive" place of Coriolanus' final scene. Certainly, of all Shakespearean scenes, its place is among the most vexed, beginning with its characters describing their location as the Volscian capital, Antium, but then near the end of the scene describing the location as Corioles. In this essay I explore the possibility that previous discussions of the scene have relied on overly simplified ideas of what place meant in Renaissance England. I wish to rethink the place of this scene for two reasons. First, most commentary regarding the place of Coriolanus' final scene is based on a fictional account of Shakespeare's state of mind during its composition, one that was invented to solve a problem of modern editorial practice and that has little to do with Renaissance performance. Second, a more historically accurate account of Renaissance place might allow us to ascribe a dramatic function for this odd change of places, which I argue is not a change but the simultaneous presence of two places. In particular, I want to argue that what we find in this scene is a concept of place that is decidedly premodern. I will suggest that in the final scene we find what Peter Platt has recently called a Renaissance "paradox of place" (121), which for Coriolanus provides a topographical correlative to the hero's own paradoxical and simultaneous place in the world.

- During Shakespeare's lifetime, place as a concept was undergoing transformation. Edward Casey describes this change as one from a sense of place that emphasized a vertical hierarchy of interrelated and dependent places to an emphasis on a linear array of discrete places related to one another through geometrical proportion.4 It was a change, as Casey describes it, from an Aristotelian sense of place to a Platonic one. Aristotle claimed that one place was always contained within another and that all places were ultimately conjoined (Aristotle, Physics 209a-12a; Casey 50-71).5 Platonic conceptions emphasized a less hierarchical, more abstract sense in which the places of the world existed in mathematical proportion to one another upon a backdrop of undifferentiated space (Plato 50c-52b; Casey 32-49).

- Changes from Aristotelian concepts to Platonic ones went hand-in-hand with other ideological transformations, primarily those in religion, science, and education. Reformed religion sought to make hierarchical church polities less hierarchical and their authorities more diffuse. The New Science sought to level Aristotelian hierarchical cosmographies, diffusing planetary bodies across the universe. And the Ramists taught from a spatialized system that made knowledge linear and schematic. In his An Anatomy of the World (1611), John Donne laments the loss of this conception of place in which resemblances (analogies and homologies, the microcosm and the macrocosm, etc.) owned meaning in the connected material and spiritual worlds. The shift was precipitated by Galileo and his "advoca[cy of] the new Copernican system" (Toulmin 83) and a gaining recognition that the older, Aristotelian cosmology had been false for millennia. This new ideological geography, Donne writes, one based on a "new philosophy [that] calls all in doubt" (205), has levelled the hierarchy from that of the planetary spheres down to that of the nation and that of the family:

'Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone;

Donne's "coherence" refers, at least implicitly, to an Aristotelian hierarchy and its structure of places, such as the mutually constituting places of "Prince" and "subject," of "father" and "son." The hierarchy-levelling "new philosophy" allows "every man" to conceive of himself as self-constituting, as a "phoenix," to be "None of that kind." The implication here, as reactionary as it is, with Donne's use of the word "kind" (and the related terms "coherence," "supply," and "relation") is that the Aristotelian system had lost a substance that held the structure together and that the new system was one of modern relativism, which Heidegger will describe as an ideology in which "every place is equal to every other" (60).

All just supply, and all relation:

Prince, subject, father, son, are things forgot,

For every man alone thinks he hath got

To be a phoenix, and that then can be

None of that kind, of which he is, but he. (213-18)

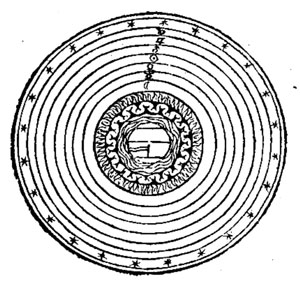

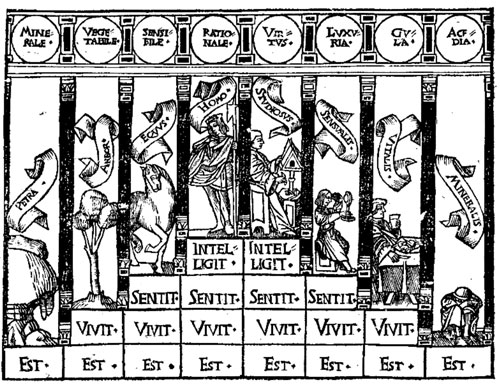

- The Aristotelian system is recorded in scores of pre-modern illustrations of a geocentric universe, where the most important entity resides at the center and its supremacy radiates throughout the hierarchical world. Figure 1 provides a typical example of this concentric structure. Figures of this type represent a lateral, view-from-above of the hierarchy which emphasizes the container and the things contained in this concept of place. Figure 2 provides a view of the vertical dimension of an Aristotelian hierarchy. We see here the typical premodern levels of "being." Beginning from the left, the figure ascends from a rock, which merely exists (est), to a plant which lives (vivit), to an animal that senses its world (sentit), and finally to a human being who thinks (intelligit). Descending to the right, the figure presents an analogy in terms of human beings: the scholar studies, the vain man gazes into a mirror, the gluttonous man eats, and finally the indolent man sleeps like a rock. More to the point, we see, however redundantly, what these orders of being share. What makes these figures particularly Aristotelian is that they all share "est," which in Aristotle's Greek is ousia and which English translations typically render as "substance." Substance, which literally means standing under, referred, in Renaissance Aristotelianism, to the being of an entity without which it could not exist and which it shared with other beings, holding together the different places of hierarchies: Donne's missing "coherence."

- One of the better guides to understanding these concepts is Kenneth Burke, who additionally points out the paradoxical character of hierarchical relationships. Burke's fundamental contribution to us here revolves around his famous phrase, "container and thing contained," which he deploys while arguing for a mutually informing relationship between a text and context. The phrase is a concise translation of Aristotle's primary definition of place as something that "seems to resemble a vessel" (Physics 209b). Both Aristotle and Burke stress that place is always contained within another place and that a single place can contain any number of other places.6 Burke himself explores how the coherence of these places results in a "paradox of substance." This paradox encapsulates the dialectical imperative in which all positive claims implicitly call forth their negatives (33)--a variation on Spinoza's omnis determinatio est negatio. Burke writes:

the word "substance," used to designate what a thing is, derives from a word designating something that a thing is not. That is, though used to designate something within the thing, intrinsic to it, the word etymologically refers to something outside the thing, extrinsic to it. Or otherwise put: the word in its etymological origins would refer to an attribute of the thing's context, since that which supports or underlies a thing would be a part of the thing's context. And a thing's context, being outside or beyond the thing, would be something that the thing is not. (23)

What Burke renders here as the structure of language, its "grammar," a large, but decreasing number of Renaissance men and women held as the structure of the universe, working in the smallest of microcosms and the largest of macrocosms.

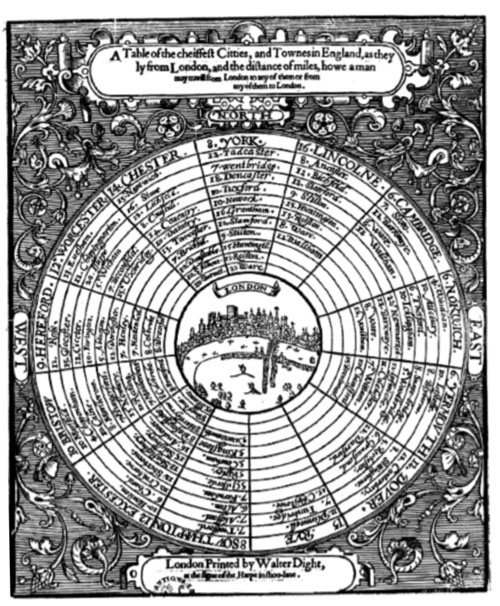

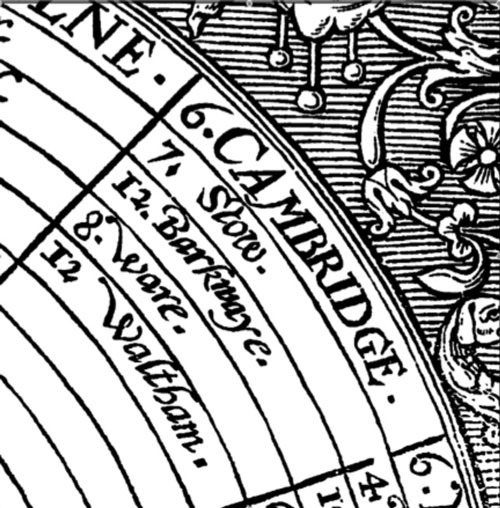

- The anonymous early seventeenth-century broadside, A Table of the Chiefest Cities and Towns in England (Figure 3),7 allows us to observe the changing status of place during Shakespeare's lifetime, for it represents the places of the kingdom as both topologically hierarchical and topographically linear. Like the geocentric cosmologies, here the places of England radiate out from a central, superior entity: London. If we could see a vertical aspect of this figure, we can be sure that the capital would stand at a superior elevation as well, sharing substance with the other places of the kingdom. London would be the single place that was substantially contained and contained by all other places in England. Appropriately, William Camden, in 1586, termed London "the epitome of all Britain" (421). In his 1604 King's Entertainment for James' Coronation, Jonson cited Camden, saying that London was so much "the glory and light of our kingdom, [that] Mr. Camden, speaking of London, saith, she is totius Britanniae epitome" (28-30). In 1599, the visiting Swiss humanist, Thomas Platter, referred to the way London simultaneously contained the whole of the kingdom in one place saying, "London is not said to be in England, but rather England to be in London" (153). The topographical locations of the cities and towns may be observed in the complicated system of numbers that the broadside prints alongside the place names (Figure 4). Each number refers to the number of miles that city or town is from the preceding city or town. Cambridge is six miles from Stow, for example, and Stow is seven miles from Barkway. Cambridge is itself forty-five miles from London, the center of the table. The table thus presents the places of the kingdom ordered ideologically as well as topographically.

- For men and women in Renaissance England, the concepts of substance and simultaneity of place, which may to modern readers appear highly metaphysical and figurative, were acutely relevant to daily life. One example concerns the nature of the Eucharist, which figured prominently in Reformation debates. At issue was if during the Mass the bread and wine changed substantially into the body and blood of Christ. If so, as Catholic doctrine held, this would mean that a natural body could be simultaneously in more places than one. Reformers argued this was impossible. As the 1552 Edwardian Book of Common Prayer's "Declaration on Kneeling" claimed, "it is against the truth of Christ's true natural body to be in more places than in one at one time" (Cressy and Ferrell 58). In its next edition, the 1559 Elizabethan Book dropped the Declaration in large measure because the population was so divided on the matter (along with most other points of contention between Catholics and Protestants). Indeed, Elizabeth desired to be as ambiguous as possible on the matter, having to deal with not only a divided population, but a predominantly Catholic House of Lords and Protestant House of Commons (Haigh 236-67). The spatial component of this division was to remain ambiguous as well, and thus, by dropping the Declaration, the state took no position on whether or not there could be a Eucharistic simultaneity of place.

- Another conspicuous manifestation of simultaneous place in Shakespeare's England was the mobile place of the king, which, as it moved around the kingdom, subsumed and therefore doubled other places. In Shakespeare's England, not only was this place conceptually available, it was materially obvious: it had a name (the "Verge"), a compass (the twelve miles surrounding the sovereign), a military force (the Knight Marshal's Men), a population (the king's mobile household), and even a legal jurisdiction with its own common law court (the Court of the Marshalsea).8 Evidence from the law courts, the Parliament and the Privy Council suggest that for the ordinary Londoner of Shakespeare's day, the king's Verge was making itself felt in often overbearing ways, ways which led the king's mobile jurisdiction to become a contested site in the battle over the nature of sovereign authority. Foremost were the Verge's juridical powers, which first came under serious scrutiny between 1596 and 1611, the period that corresponds to what is thought of as Shakespeare's "great" period (beginning with The Merchant of Venice and 1 Henry IV and ending with The Tempest). At issue were the corrupt practices of the Court of the Marshalsea, which would send out the Verge's military force, who would arrest any number of individuals under false charges for the sake of collecting a fee. When the Verge would resume its progress, matters such as these would be dropped. No justice would be given and no fee returned. According to the 1606 draft of "An Act for Reformation of Abuses and Due Execution of Justice in the Court of Marshalsea," "by the ill conduct of the officers, called marshals, the court is scandalized and the subjects oppressed" (Great Britain 118). These practices were common enough that if one were unfortunate enough to get caught in the king's Verge, one would be advised to make oneself scarce.

- Francis Bacon claimed the place of the king, the Verge, was "exempt" and likened it to a free-floating "half-pace or carpet spread about the King's chair of estate" (266). "Half-pace" (otherwise known as a halpace) is a "platform at the top of steps, on which an altar stands" or a "step, raised floor, or platform, on which something (e.g. a throne, dais, etc.) is to be placed or erected" (OED 1b and a). The image works for two ways of conceiving of the simultaneity of place. The first way is the stepped hierarchy we saw in the illustration above which emphasized the sharing of substance on different levels of being. The second way emphasizes Bacon's term "exempt" and its implications for the mobile nature of the king's place. Etymologically the Verge is exempted because it is "taken out" (ex- "out," emere "to take") of the orthodox requirement that places be stationary and that subjects of the kingdom keep to these stable places as a matter of order. As the "Exhortation Concerning Good Order" (1559) stated, "where there is no right order,"

there reigneth all abuse, carnal liberty, enormity, sin and Babylonical confusion. Take away kings, princes, rulers, magistrates, judges, and such states of God's order, no man shall ride or go by the highway unrobbed, no man shall sleep in his own house or bed unkilled. (Aughterson 93)

The Verge is a "half-pace" because the king's place remains stable but only in relation to the person of the sovereign, as if this place were a scaffold or a stage that would come to rest on top of and thus subsume the places of others. This doubling of place implies as well a sharing of substance, much like that represented in the figures above. When the king or queen came calling in Shakespeare's day, he or she had use of the subject's substance--that is, the subject's material goods and services, that which "stands beneath" supporting the subject now stands beneath both the subject and the sovereign.9

- The Verge and its exempt status also point to a state of paradox, signaled in the first place by the paradoxical nature of the very word "exempt." Giorgio Agamben speaks of the paradox of the related word "exception," whose etymology contains the prefix ex- and a root, capere, that, like emere, means "to take" (18). Taking, Agamben notes, is an inclusive act, which stands antithetical to the outward gesture of the ex-.10 In the second place, the sovereign's place was paradoxical because the Verge was the ground-zero of geographical ideology. In James I's absolutist terms, the Verge not only contained the king's household, but the king was himself the pater patriae. Not only was the king charged with keeping his household safe, he was defensor pacis of his kingdom. And not only was the king responsible for finding justice for his family, he was fons justitiae for the men and women of Britain. Francis Bacon was working within this ideological geography when, in defence of the king's jurisdiction, he noted that the Verge should be "exemplary unto other places" (266). The Verge, from this perspective, was "exemplary" in that it served as an especially illustrative example of family, peace, and justice as well as the source of these qualities which it circulated throughout the rest of the kingdom. The paradoxical aspect of these formations was that while subject places were thought to depend on the exemplary and exceptional place of the sovereign, the place of sovereign depended on the substance of its people. For this very reason did the Verge on progress require a host within which to reside. For this very reason did the Knight Marshal's Men shakedown the king's subjects wherever the Verge settled. Agamben terms this the "paradox of sovereignty" in which the Aristotelian-based political structure requires a dependent relationship between greater and lesser status positions.11 As I will discuss below, this very paradox in which the highest of places must stoop to the lowest makes for an unsurpassable impediment for the hero of Shakespeare's Coriolanus.

***

- Important for discussion of place and Renaissance drama, we see these changes in the relational and ordering properties of scene designations first incorporated into Shakespeare's plays at the beginning of the eighteenth century. During the eighteenth century, Shakespeare's editors began locating the scenes of his plays with increasing specificity; they also, by virtue of locating each and every scene, created structural relations among them that follow what Casey and Ong find as a general cultural trend.12 Henry Turner has recently argued that this modern, abstract space has the ability to hold any number of locations simultaneously. His claims follow neatly those of Ong because Turner describes this abstract space as a "readerly" one--one opposed to the verbal / performative space of the theater.13 For Turner, in fact, the modern, written imposition of acts and scenes allows for this experience of simultaneity. The audience in Shakespeare's theater observed the places of the drama serially: place was not simultaneous because the place of one scene followed the place of the previous scene. A reader, by contrast, can conceive of such a simultaneity because he or she can think of the play in its entirety, in a "space of simultaneity" provided by the "'structural' theories of act and scene divisions" which enable "the reader to project across the play in its entirety a homogeneous, unbroken, 'containing' space that is imagined to link or underlie the various 'places' of the fiction" (180).

- However helpful Turner's binary may be, it fails to account for conceptions of simultaneity that come from the hierarchical nature of premodern place. To say that two (or more) places could not have been experienced by a Renaissance audience in the theater is to treat that audience as if it were a modern one--one whose concept of place is generally non-hierarchical. What we witness, however, in the historical record is a kind of simultaneity conceptually available to audiences in Shakespeare's England because of an ideological geography in which places of authority were arranged in hierarchical and concentric schemata.

- In Coriolanus, the plebeians largely accept the Aristotelian conception of place. When prompted, for instance, by the Tribune Sicinius, "What is the city but the people?" they respond, "True, / The people are the city" (3.1.199-200). And however grudgingly she may accept it, Volumnia notes that, in order to become consul, Caius Martius must go to the marketplace and "stand for his place" before "the people" (2.1.134-135).14 She seems to understand the inherent paradox wherein those in the highest of places share something of that place (something substantial) with those in the lowest. Her son, Caius Martius, by contrast, has a morbid conception of such consubstantiality, which we see when he enters the play and fantasizes genocide against the Plebeians. He imagines a literal elevation of place atop their corpses:

Would the nobility lay aside their ruth

Caius Martius thus enters the play using a figure that has the effect of militarizing the rhetorical: insultatio, the quintessential figure of the warrior.15 Insultatio, in its etymological sense, refers to the rejoicing the triumphant warrior performs on top of his dead enemy.16 As T. W. Baldwin notes, Shakespeare was thinking of this sense of insultatio when he has Cloten say how he will treat Posthumus: "He on the ground, my speech of insultment ended on his dead body" (Cymbeline 3.5.136-138; Baldwin 2.159). If the use of Caius Martius' sword is a physical manifestation of his violent nature, then his insultatio is the verbal manifestation of the same. From this figure and the way it assumes an elevated place for the warrior, we can imagine Caius Martius' ideological geography conceiving of the political structure only as the most ideologically blinkered warrior could: standing triumphant atop the defeated corpse of the other. Kenneth Burke might remind us that a corpse is the container with an absence of the thing contained. Caius Martius' figure has the effect, therefore, of denying that he shares anything of substance in common with the Plebeians. Importantly, he alludes to this very figure upon being banished by them, saying that their "loves" he "prize[s] / As the dead carcasses of unburied men / That do corrupt my air: I banish you" (3.3.125-127).

And let me use my sword, I'd make a quarry

With thousands of these quartered slaves as high

As I could pitch my lance. (1.1.186-189)

- Caius Martius nevertheless conceives of place in vertical terms. He claims that his objection for adding tribunes of the people to the Senate body is that it does damage to the vertical order of things. In an important figure, he describes the changes in the structures of authority in terms of hierarchy and place. He says:

when two authorities are up,

Caius Martius imagines, then, the changes in structures of authority as a change from an Aristotelian sense in which places are contained by other places to one in which places are set in relation to one another within a void of unorganized space. "Gap," translated into its Greek equivalent, is chaos, which is precisely what surrounds the places of emerging conceptions of the spatial universe. Caius Martius fears Heidegger's description (also quoted above) of an ideology in which "every place is equal to every other."

Neither supreme, how soon confusion

May enter 'twixt the gap of both and take

The one by th' other. (3.1.112)

- Faced with conceiving of the Plebeians as sharing something of substance with him and the patricians, and disabused of the fantasy of a hierarchy of corpses, Caius Martius imagines an un-girding in which the hierarchal cosmology of places becomes an array of linearly related locations. What frightens him is the dialectical ebb-and-flow of the "two authorities." He imagines this interchange not only as a "confusion" but as one that brings the authorities together in a violent embrace, "the one by th' other," which is precisely the figure of two, equally matched warriors in the embrace of combat. Aufidius describes this, famously, as a recurring dream he has had of being "down together" with Caius Martius, "Unbuckling helms, fisting each other's throat" (4.5.123, 124). It is a dream from which he would, suggestively, "awake[n] half dead with nothing" (4.5.125).

- By the time Caius Martius enters the final scene, however, he has exchanged his warrior ethos of "violent'st contrariety" (4.6.76) for a diplomat's "reconcil[iation]" (5.3.137). Indeed, in his attempt to win a peace between the city-states of Rome and Antium, he attempts to replace his figure of the two authorities that, set side-by-side, breed confusion with one of sharing. He enters the final scene of the play explaining that he has "compounded" (5.6.84) a peace.17 More to the point, the play places together two otherwise discrete locations: the town of Corioles (for whose conquest Caius Martius gained the honorific "Coriolanus") and the city-state Antium (the Volscian capital, Aufidius' hometown, and the city Caius Martius now serves). The scene begins with the Volscian hero Aufidius speaking with a group of conspirators--conspirators he has contracted to help kill Caius Martius. Aufidius is uncertain whether it is the right time to get rid of the man who had promised to lead the Volsces to victory over Rome but who instead has been persuaded by Volumnia, his mother, to negotiate a treaty. The conspirators wish to do the job immediately and they convince Aufidius of their position on two points. First, they argue that Aufidius cannot have the support of the Volscian people and its military while Caius Martius is still alive and "seducing" (5.6.23) them. Second, they argue that Caius Martius has just arrived in such a way as to further alienate Aufidius from the Volsces; Caius Martius made him look like his messenger boy. Upon hearing "Drums and trumpets" and "great shouts of the people" (folio stage direction), the First Conspirator says, "Your native town you entered like a post / And had no welcomes home; but he returns / Splitting the air with noise" (5.6.49-51). Moments later, Aufidius does receive his "welcomes home," not from the Plebeians as Caius Martius has received them, but from the Lords of the City, who say, "You are most welcome home" (5.6.60).

- At this point in the scene, many Renaissance audience members would probably have understood by these uses of the word "home" that the location of this scene was Antium, which the play has taken pains to explain is both Aufidius' hometown (3.1.18-19; 4.4.8-11.) and the Volscian capital.18 Only moments later, however, when Caius Martius enters the scene, the audience is given a wholly different place in which to locate the scene. Aufidius speaks to the returning hero, calling him "Martius." He recoils. "Martius?" he asks. Aufidius responds: "Ay, Martius, Caius Martius. Dost thou think / I'll grace thee with that robbery, thy stol'n name, / 'Coriolanus' in Corioles?" (5.6.90-92). Although the scene began in Antium, it now seems located in Corioles, for Aufidius' words means something to the effect of, "Do you think I'd call you 'Coriolanus' here in Corioles?"

- The significance of the change of place will become clearer if we take a few moments to contrast the status of the play's hero as he enters here and at the beginning of the play. As he walks into the play's final scene, it is abundantly clear that the Roman hero has added to his many military conquests the winning of the hearts and minds of the Volscian people. It is a remarkable change for a character who had been so hated by the Roman people that they had only recently banished him due to his insolence toward them. But here Caius Martius, in Aufidius' words, "Intends t'appear before the people, hoping / To purge himself with words" (5.6.7-8), which, according to the folio stage directions, he appears to accomplish. First, the stage directions say, Caius Martius is greeted off stage by "great shouts of the people"; second, he enters the scene "marching with drums and colors, the Commoners being with him." Moreover, Caius Martius' change of heart is tantamount to a change in ideological geography in that he understands his successes are contingent upon the support of the Plebeians' voices, which are represented here in the final scene as the "great shouts of the people." He accepts what Wayne A. Rebhorn calls the "paradoxical view of the rhetor-ruler" in which "the rhetorical performance of rule actually makes the [ruler] the 'subject' of his subjects" (77, 79). Discussing the image of Hercules Gallicus (Figure 5), whose rhetorical power was often pictured by chains leading from his mouth and linked to his auditors' ears, Rebhorn says that the chains reveal not only "an indication of Hercules' dominance but as a sign of linkage, of mutual attachment, between the hero and his people, an indication that neither Hercules nor his subjects can maintain their positions and identities independent of one another" (74). For most of the play, Caius Martius views this dialectical relationship negatively, believing that the act of persuading the "mutable rank-scented meinie" (3.1.70) contaminates the speaker. When it comes to dealing with the Plebeians, he would rather use his words as if they were swords because he believes that entering into dialogue with them would only lead to him becoming infected with their unwholesomeness. This is precisely what he means by saying that his "lungs" will "Coin words . . . against those measles / Which we disdain should tetter us, yet sought / The very way to catch them" (3.1.80, 81-84). Additionally, he imagines the act of persuading his social inferiors an ignoble act; "Better it is to die, better to starve," he says, "Than crave the hire which first we do deserve" (2.3.103-04). When, at the insistence of his mother, he does attempt to perform in this way, he fails miserably. He fails to the extent that the people banish him. By the time he enters the final scene, his attitude has changed. He enters surrounded by cheering Volscians, showing that he is doing among them what he has learned to do at Rome. No longer is the marketplace the place he cannot reconcile himself to. As Aufidius has correctly predicted, "All places yields to him ere he sits down, / And the nobility of Rome are his. / The senators and patricians love him too"; moreover, Aufidius says, the Plebeians "Will be as rash in the repeal as hasty / To expel him thence" (4.7.28-30, 32-33).

***

- For almost a century and a half, Shakespeare's first modern editors did not see the final scene's double place as a problem. Nicholas Rowe, the first editor to designate explicitly the location of each scene, began in 1709 the tradition of setting the scene in Antium. These first editors set the scene there, we can assume, because they understood the conventional way in which dialogue that opens a scene communicated location to Renaissance audiences. S. W. Singer followed this conventional setting in his first edition of the play, but some thirty years later for his second edition, in 1856, he re-set the scene, explaining, "The place of this scene has been hitherto marked at Antium, but from what Aufidius says . . . , it must have been at Corioli" (442). In the century and a half between Rowe's and Singer's editions, did editors begin to "forget" the standard of locating a scene in its opening dialogue? Or did the increasing textualization of Shakespearean works and the increased professionalization of the task of editing create a new paradigm for how a scene might be located? Either way, the change Singer introduced set in motion sixty years of editors arguing back-and-forth about where the scene was "really" set. Some located it in Antium, others in Corioles.

- In 1912, George S. Gordon came upon a "solution" that promised to unite editorial opinion.

Editors are divided whether to place this scene in Antium or

We should note that Gordon places the scene both in Antium and in Corioles. We should note additionally that Gordon here is theorizing in terms of seriality, which as we have learned from Henry Turner, is a way of conceiving of place primarily vis-à-vis performance (161-185). One place comes after the other, as the play moves from scene to scene. The difference here, according to Gordon, is that this serial movement from one place to another occurs within the confines of a single scene. The reason Gordon proposes this odd intra-scenic movement is that his solution solves a problem of modern editing, not a problem of Renaissance drama. We have no evidence that the simultaneous place of the final scene was a problem for Shakespeare and his audience; there does not even seem to have been a problem for modern editors until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Corioli . . . . The solution seems to me to be this. Shakespeare

meant the scene to be Antium, and wrote with Antium in his mind

until he came to Aufidius' speech . . . . There he was carried

away by the magnificent opportunity of placing 'Coriolanus in

Corioli' . . . and for the rest of the scene thought rather of

Corioli than of Antium. (139)

- What has become obscured over time is the fact that Gordon's narrative is an interpretation. Editors of the play in the years just following Gordon's "solution" told readers that they were persuaded by Gordon's hypothetical narrative, saying with all candor that it seemed likely that Shakespeare had given in to his poetic mind and created a problem. More recently, however, many editors fail to mention that Gordon's solution was but a hypothetical possibility. John Dover Wilson, in his Cambridge edition of 1960, says without qualification that "Clearly Shakespeare changes his mind." Philip Brockbank, in his second series Arden edition of 1976, also claims without qualification that "the dramatic advantage of 'Coriolanus in Corioles' proved irresistible." And Lee Bliss, in her New Cambridge edition of 2000, notes that Shakespeare "seized on the dramatic possibilities of 'Coriolanus' in Corioles."

- Alan Dessen accepts Gordon's hypothesis at the same time that he resists editorial interventions that impose modern ways of thinking on the premodern text. While I will ultimately disagree with his conclusions, his ideas have the helpful quality of centering on how these two places work in the drama. Dessen argues that Shakespeare changes the location of the scene not for the effect of a double place, but for the effect of the line "'Coriolanus' in Corioles." In his version, instead of blaming Shakespeare for a "mistake," Dessen praises Shakespeare for "apparently choos[ing] to have it both ways." Dessen goes on to explain that "To fix the place as either Antium or Corioli is to impose our rigidity upon Shakespeare's chameleon stage and to blunt part of the effect of this climactic scene" (86).

- I would add, however, that we are imposing our rigidity when we assume that the final scene cannot be set in two places at once. That is, while I agree with Dessen warning us not to impose our modern, rigid notions of place on a premodern drama, I argue that he is being too modern when he assumes that there must be a change of places at some point in the scene. I am suggesting that while Shakespeare had it both ways, so too did his audience and his characters. In a way, Caius Martius makes this point himself when he enters the final scene owning the paradoxical identity of both a Roman diplomat and a Volscian warrior; he is simultaneously "of" each city-state. We may even imagine him as an ambassador, who would therefore own something like a Verge, an exempted "half-pace" of Rome surrounding him there in another polis.19 He is, then, both in Roman and in Volscian territory. Indeed, Caius Martius enters the final scene speaking in a highly stylized paradox in which he figures himself as encompassing "two authorities." He greets the lords of the city,

Hail lords! I am returned your soldier,

Caius Martius claims, then, the paradoxical identity of a warrior and a maker of peace. He allows, moreover, that he is "of" two city-states: he is at some level "infected" with "love" of Rome at the same time that he is a member of the Volscian military hierarchy (he "subsist[s] under [their] great command," he claims). Caius Martius does more than simply represent himself in paradoxical terms. This is a character who has hitherto been unable to utter a circumlocution, who has only been able, he says, to "play / The man I am" (3.2.14-15), who in many ways characterizes the Renaissance plain-speaker in extremis, but who nevertheless produces here the most deceptively equivocal utterances in the play.20 Of particular interest are the conditionals that practically bookend the address, one in the form of "no more . . . than," the other "no less . . . than." The first equivocates in that it hides the degree to which Caius Martius is "infected" with patriotism; the negation does not deny that he owns love for his country, it is only "no more than" an earlier moment. Still, as a negation, it suggests that he is explicitly denying something, something that would assure the Volscians of his fidelity, while under closer reading, he is denying very little. The second conditional equivocates, suggesting that the Romans have suffered shame, while a closer reading reveals that he has made no such positive claim. His negation merely says that shame to the Romans outweighs loss of honor for the Volscians. In his diplomatic role, however, Caius Martius aims precisely for a reconciliation in which the Romans suffer no shame and the Volscians gain no honor. Overall, he gives the impression that, first, he remains a Volscian subject of the war; second, his expedition has profited them; and third, these things have caused shame to the Romans. None of these impressions could withstand serious scrutiny, for although a subject of the Volscian military machine, much like the Roman Plebeian soldiers before Corioles, he refused to enter the gates of Rome; although the expedition may have yielded a net profit, it is nothing compared to the spoils he would have had if he had sacked Rome; and although the Romans may have indeed suffered some shame in begging for mercy and negotiating a peace, it pales in comparison to the shame they would have incurred upon being defeated by the very protector whom they had recently exiled. Antium's honor, likewise, pales in comparison to what it might have been.

No more infected with my country's love

Than when I parted hence, but still subsisting

Under your great command. You are to know

That prosperously I have attempted, and

With bloody passage led your wars even to

The gates of Rome. Our spoils we have brought home

Doth more than counterpoise a full third part

The charges of the action. We have made peace

With no less honor to the Antiates

Than shame to th' Romans. And we here deliver,

Subscribed by th' consuls and patricians,

Together with the seal o' th' Senate, what

We have compounded on. (71-84)

- However little these locutions say about their purported subjects, they speak volumes about Caius Martius' change of character. Caius Martius has heretofore termed himself "constant" and has violently disdained multiplicity and doubleness, yet he has of a sudden become a person of two countries, claims the paradoxical status of a soldier of peace, and speaks in figures of duplicity. He has become politically and ontologically double. He has become much like the stage players whom Philip Stubbes, in his anti-theatrical Anatomy of Abuses (1583), termed "double-dealing ambidexters" (141) and whom Caius Martius allusively derides, saying that he will not perform like an actor in the marketplace but will "play / The man I am." Caius Martius has additionally become rhetorically double, not just because he uses the language of paradox but because he enters into the paradoxical relationship of the rhetor and his audience, about which I described above. This fragmentation of the self is furthermore emphasized by an ironic turn, for while Caius Martius termed the citizens of Rome "fragments" (1.1.212) in the play's opening scene, here in the closing scene it is the Volscian citizens who wish to turn him into fragments, calling for his dismemberment: "Tear him to pieces!" (5.6.121), they say.21

- Given this new, double nature of the tragedy's hero as he walks onto the stage for a final time, and given as well a Renaissance audience equipped with an ideological geography that allowed for a regular doubling of place (as in concepts of the Verge and of Eucharistic consubstantiality), one may very well wonder why critics and editors have not previously imagined the paradox of a scene that was located in two places at once functioning as a topographical correlative to a hero whose place in the world is likewise paradoxical and doubled.22 This connection has not been obvious to us because we have not been thinking about place in the same way that Renaissance audiences thought about place. The simultaneous place of the final scene was originally understood in what Foucault called "the age of the theater," a time in which phenomena were presented simultaneously so that an audience might apprehend resemblances and analogies. Foucault called the following age the age of the "catalogue," a time in which phenomena were presented linearly for the purposes of an analytical "pure tabulation of things" (Order 131).23 This later age was in fact the age in which editors began giving each Shakespearean scene its own single, discrete location.

- Furthermore, the audience member of Shakespeare's public theater would have understood the simultaneity of place not just conceptually but materially, seeing the places of the fiction represented simultaneously by the structures of the stage itself.24 In Coriolanus, for example, the balcony from which the Senators of Corioles taunt Caius Martius remains there throughout the performance, signifying, however peripherally, that single place, no matter where else the action on the stage took the play. The two or three doors along the tiring house wall, which would have been used to represent entrances into the public places of Rome and Antium and doorways into the Senate house as well as the houses of Volumnia and Aufidius--these doors remained on the stage, visible to the audience throughout the play, eliciting the various places of the play not in any discrete manner but in a way that elicited what Foucault referred to as "a complex of kinships, resemblances, and affinities . . . in which language and things were endlessly interwoven" (Order 54).25

- If we were to apply our understanding of the Renaissance ideological geography in which these resemblances and analogies participated, we may very well re-imagine certain problems in Shakespeare's plays. I am persuaded by Lukas Erne, who argues against those who would have us read "unedited" texts and instead makes the case that modern editorial practice is both necessary and good. "[A]ll in all," Erne claims, editors'"decisions and interventions have an enabling effect, allowing today's readers to engage with Shakespeare's drama with greater ease and insight" (4). Modern editors may thus very well continue to rehearse the account of Shakespeare negotiating his dualistic mind, but they should consider once again citing George S. Gordon, the modern editor who developed the account. Modern editors may perhaps even wish to note that the double setting was not a problem until over two hundred years after the publication of the first folio (1623-1856). Future editors may as well wish to note that given a Renaissance ideological geography, the double setting in Coriolanus may not be so much a "problem" to fix, but an opportunity to re-interpret the place of the final scene and re-imagine our assumptions about place in Shakespeare's plays.

The author wishes to thank Alan Dessen, Kelly Eskew, Greg Foran, Marissa Greenberg, Jon Lamb, Jennifer Lowe, and James Mardock. Special thanks go to Rodney Herring, Vim Pasupathi, Wayne Rebhorn, and Frank Whigham.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1998.

---. Il Potere Sovrano e la Nuda Vita. Torino: Einaudi, 1995.

Aristotle. The Physics. Trans. Philip H. Wicksteed and Francis M. Cornford. Vol. 1. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1980.

Aughterson, Kate, ed. The English Renaissance: An Anthology of Sources and Documents. London and New York: Routledge, 2001.

Baldwin, T. W. William Shakspere's Small Latine & Lesse Greeke. Vol. 2. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1944.

Beckerman, Bernard. Shakespeare at the Globe, 1599-1609. New York: Macmillan, 1962.

Behrens, B. "Treatises on the Ambassador Written in the Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Centuries." The English Historical Review 51 (1936): 616-627.

Bevington, David. Action is Eloquence: Shakespeare's Language of Gesture. Cambridge and London: Harvard UP, 1984.

Blitefield, Jerry. "Aristotle, Kenneth Burke, and the Transubstantiation of Place." Rhetorical Agendas: Political, Ethical, Spiritual. Ed. Patricia Bizzell. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2006. 117-122.

Bruster, Douglas. Drama and the Market in the Age of Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992.

Burke, Kenneth. A Grammar of Motives. 1945. Berkeley: U of California P, 1969.

Camden, William. Britain. Trans. Philemon Holland. London: 1607.

Casey, Edward. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History. Berkeley: U of California P, 1997.

Chapman, George. Chapman's Homer. Vol. 1. Ed. Allardyce Nicoll. New York: Pantheon, 1956.

Christensen, Ann C. "The Return of the Domestic in Coriolanus." SEL 37 (1997): 295-316.

Cressy, David and Lori Anne Ferrell, ed. Religion and Society In Early Modern England: A Sourcebook.2d ed. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Day, Angel. The English Secretary. 1599. Gainesville: Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, 1967.

Dessen, Alan C. Elizabethan Stage Conventions and Modern Interpreters. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984.

Dillon, Janette. The Cambridge Introduction to Early English Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006.

Donne, John. The Major Works. Ed. John Carey. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000.

Erne, Lukas. Shakespeare's Modern Collaborators. London and New York: Continuum, 2008.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage, 1995.

---. The Order of Things: an Archeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage, 1994.

---. Les Mots et les Choses: Une Archéologie des Sciences Humaines. Paris: Gallimard, 1966.

Fumerton, Patricia. Unsettled: The Culture of Mobility and the Working Poor in Early Modern England. Chicago and London: Chicago UP, 2006.

Gillies, John. "Space and Place in Paradise Lost." English Literary History 74 (2007):27-57.

Graham, Kenneth J. E. The Performance of Conviction: Plainness and Rhetoric in the Early English Renaissance. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 1994.

Great Britain. Fourth Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Part I. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1874.

Greene, Douglas G. "The Court of the Marshalsea in Late Tudor and Stuart England." American Journal of Legal History 20 (1976): 267-281.

Haigh, Christopher. English Reformations: Religion, Politics, and Society under the Tudors. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1993.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. London and New York: Penguin, 2004.

Hattaway, Michael. Elizabethan Popular Theatre: Plays in Performance. London: Routledge, 1982.

Hershey, Lewis B. "Burke's Aristotelianism: Burke and Aristotle on Form." Rhetoric Society Quarterly 16 (1986): 181-185.

Hobbes, Thomas. On the Citizen. 1651. Ed and Trans. Richard Tuck and Michael Silverthorne. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998.

Holland, L. Virginia. Counterpoint: Kenneth Burke and Aristotle's Theories of Rhetoric. New York: Philosophical Library, 1959.

Jones, W. R. "The Court of the Verge: the Jurisdiction of the Steward and Marshal of the Household in Later Medieval England." The Journal of British Studies 10 (1970): 1-29.

Jonson, Ben. Ben Jonson. Ed. C, H, Herford and Percy and Evelyn Simpson. Vol. 7. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1952.

Kuzner, James. "Unbuilding the City: Coriolanus and the Birth of Republican Rome." Shakespeare Quarterly 58 (2007): 174-199.

Mahood, M. M. Playing Bit Parts in Shakespeare. London: Routledge, 1998.

Marcus, Leah. Puzzling Shakespeare: Local Reading and its Discontents. Berkeley: U of California P. 1988.

Menzer, Paul. "Dislocating Shakespeare: Scene Locators and the Place of the Page." Shakespeare Bulletin 24 (2006): 1- 19.

Montrose, Louis. The Purpose of Playing: Shakespeare and the Cultural Politics of the Elizabethan Theatre. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1996.

Mullaney, Steven. The Place of the Stage: License, Play, and Power in Renaissance England. 1988. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1995.

Ong, Walter J., S.J. Ramus, Method and the Decay of Dialogue: from the Art of Discourse to the Art of Reason. 1958. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 2005.

Orgel, Stephen. The Illusion of Power: Political Theater in the English Renaissance. Berkeley: U of California P, 1975.

Parker, R. B. Introduction. The Tragedy of Coriolanus. Ed. R. B. Parker. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 1994.

Plato. Timaeus. Plato with an English Translation. Vol. 7. Loeb Classical Library. Trans. W. R. M. Lamb. London: Heinemann and New York: Putnam, 1913.

Platt, Peter G. "'The Meruailouse Site': Shakespeare, Venice, and Paradoxical Stages." Renaissance Quarterly 54 (2001): 121-154.

Puttenham, George. The Art of English Poesy. 1589. Ed. Wayne A. Rebhorn and Frank Whigham. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2007.

Rebhorn, Wayne A. The Emperor of Men's Minds: Literature and the Renaissance Discourse of Rhetoric. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 1995.

---, ed. and trans. Renaissance Debates on Rhetoric. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 1999.

Rumrich, John. "Milton's God and the Matter of Chaos." PMLA 110 (1995): 1035-1046.

Schmitt, Charles B. Aristotle and the Renaissance. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1983.

Shakespeare. Coriolanus. Ed. Lee Bliss. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000.

---. Coriolanus. Ed. Philip Brockbank. The Arden Shakespeare, 2nd series. London: Methuen, 1976.

---. Coriolanus. Ed. George S. Gordon. The New Clarendon Shakespeare. Oxford: Clarendon, 1912.

---. Coriolanus. Ed. John Dover Wilson. The Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1960.

---. The Norton Shakespeare. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard, and Katherine Eisaman Maus. New York and London: Norton, 1997.

Sidney, Sir Philip. "The Defence of Poesy." Sidney's the Defence of Poesy and Selected Renaissance Literary Criticism. Ed. Gavin Alexander. New York: Penguin, 2004. 1-54.

Stubbes, Philip. Anatomy of the Abuses in England. 1583. Ed. Frederick J. Furnivall. London: New Shakespeare Society, 1877-79.

Toulmin, Stephen. Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1992.

Turner, Henry S. The English Renaissance Stage: Geometry, Poetics, and the Practical Spatial Arts, 1580-1630. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006.

Weimann, Robert. Author's Pen and Actor's Voice: Playing and Writing in Shakespeare's Theatre. Ed. Helen Higbee and William West. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000.

Wickham, Glynne. Early English Stages, 1300 to 1660. Vol. 2, part 1. London: Routledge, 1963.

Yiu, Mimi. "Sounding the Space between Men: Choric and Choral Cities in Ben Jonson's Epicoene; or, The Silent Women." PMLA 122 (2007): 72-88.

Notes

1 All quotations of Shakespeare come from The Norton Shakespeare.

2 On the protective function of the simultaneity of place, see Marcus 160-211.

3 For other critics who explore simultaneity of place, see Fumerton 53-59, Platt, Turner 166-185, Weimann 70, 93, 180-215.

4 On the work of Casey and Shakespeare, see Menzer 16-17 and Weimann 188 and 214. Weimann emphasizes the way both Aristotelian and Platonic perspectives were simultaneously active in the ideological threshold of early modernity. On the work of Casey and Milton, see Gillies, passim. For a different perspective on the conceptions of place and Shakespeare's stage, see Turner 162-63 and 177. For a similar perspective (via Cassirer), see Mullaney 17-20. On the use of Platonic cosmology during the Renaissance, see Rumrich 1035-40 and Yiu 74-77.

5 Recently, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri describe political power in ways homologous to Aristotelian and Platonic views of place and space. "Empire" has a "network of hierarchies and divisions that maintain order," while the "multitude" has "circuits of cooperation and collaboration that stretch across nations and continents and allow an unlimited number of encounters" (xiii). If Empire thrives on imposing an old-fashioned hierarchy, the multitude thrives on taking advantage of its ability to create an internet-like "swarm" (91).

6 On the influence of Aristotelian thought and the conception of place in Renaissance England (and its theater), see Turner 45-50. On Renaissance Aristotelianism, see Schmitt. On Aristotelian thought in the work of Kenneth Burke, see Blitefield, Hershey, and Holland.

7 Some readers will be familiar with this illustration from the cover of the collection, Material London, ca. 1600.

8 Although the jurisdiction of the Verge was of particular importance to medieval and Renaissance England, modern scholarship has paid it little attention. For two of the only article-length discussions it, see Greene and Jones. In studies of Shakespeare, the phenomenon practically lacks any mention whatsoever. For the only example I know of, see Mahood 218.

9 On the dialectical nature of the sovereign and the subject, see Montrose 16. On the king's half- pace and Renaissance theater, see Dillon 60-61 and Orgel 9-10.

10 Agamben is subtler than am I in his unfolding of this paradox of etymology, saying that "the exception is truly, according to its etymological root, taken outside (ex-capere), and not simply excluded" (18) ["l'eccezione è veramente, secondo l'etimo, presa fuori (ex- capere) e non semplicemente esclusa" (22)].

11 "Il paradosso della sovranità" (19). For a description of the mutually constituting nature of the body of the sovereign and "the least body of the condemned man," see Foucault, Discipline 28-29. See also the related figure in Coriolanus where one of the starving Plebeians complains of the nobility that "The leanness that afflicts us . . . is as an inventory to particularize their abundance" (1.1.16-17). A longer version of this essay includes a description of how the Plebeians function as a low, oppositional double to the hero of the play who cannot comprehend, until it is too late, the paradoxical and mutually informing relationship between the highest and the lowest, the greatest and the least. For a different interpretation of the Agambenian aspects of the play (one that blames the Plebeians for their willingness to take part in deliberative politics and praises Caius Martius for his willingness to expose himself to the violence of the battlefield in order to "erode the borders of his social and bodily self" [189]), see Kuzner 188-99.

12 On the advent of editorial scene designation, see Bentley 53-63, Dessen 84-104, and Turner 165-166. On the movement from place to space in Shakespeare's theater, see Turner 180-185 and Menzer, passim.

13 Ong famously argues for a general change in Western epistemology, from one based on verbal dialogue to a "hypertrophy of the visual imagination" that "crowds spatial models, and nothing but spatial models, into the universe of the mind." It is, he tells us, "the evolution in human thought processes which is simultaneously producing the Newtonian revolution, with its stress on visually controlled observation and mathematics, and its curiously silent, nonrhetorical universe" (318). For similar interpretations of the changing ideological geography in the West, see Foucault, Discipline and Punish 187-194 and The Order of Things 17-30. See also, Toulmin 45-87.

14 I refer to the hero of this play not by his honorific name, "Coriolanus," but by the name with which he begins the play, "Caius Martius." The problem with calling him Coriolanus is one of anachronism, because at first he has yet to be given that name and, later on, he gives it up. It is true that in his march on Rome we are told that he has given up all names and that he exists as "a kind of a nothing, titleless, / Till he forged himself a name o' th' fire / Of burning Rome. (5.1.8-15). Terming him any single name risks anachronism, since at one point he has none. Still, given the choice between referring to him by different names (or none) as the context requires, or referring to him by the one which is applicable at most times, I have chosen the latter.

15 See also Parker's assessment of Caius Martius' "'driven' syntax" as the "rhetorical equivalent of his conduct on the battlefield" (75). During the Renaissance, the the violence of rhetoric and the violence of the battlefield were often imagined as related. No less authority than Agricola shared the Renaissance commonplace opinion that argument "produces belief in the auditor--just as if one were waging a military campaign" (Rebhorn, Debates 46). See also Hobbes, who in his On the Citizen states that "the war of the sword and the war of the pens is perpetual" (5).

16 Insultare, meaning "to spring or leap at or upon a thing" comes from a combination of the preposition in-, "on," and the verb salire, "to leap, spring, bound, jump" (Lewis and Short). On insultatio, see Day 89 and Puttenham 294. Puttenham, who also calls it "the Reproachful or Scorner," alludes to its martial roots, saying that insultatio is "when with proud and insolent words we do upbraid a man, or ride him, as we term it." See also Chapman, whose Homer often notes when a character uses this figure. One marginal note reads, for instance, "Hector's insultation over Patroclus, being wounded under him" (c. 16.762) A later note reads, "Hector, wounded to death. Achilles'insultation" (c. 22.285).

17 Etymologically, then, he has "placed together" the city-states, for "compound" comes from the Latin pono (and whose fourth principal part, positum, gives us the English word "position"), meaning to place.

18 We might also note that Shakespeare's source, Plutarch, has Caius Martius return there, and, as the capitol, it is quite reasonably the place where one would return to deliver and celebrate a newly agreed upon treaty.

19 On the sovereignty of an ambassador's mobile place, see Behrens 623-624.

20 On Caius Martius as a Renaissance plain-speaker, see Graham 168-189.

21 See Christensen, who interprets the commoners, rather than the conspirators, as those who kill the hero: "The 'puny battle' waged by the Volscians against Marcius at the end appears as a nightmare return of the repressed. It is after all the widows and orphans--the fragments of family--of Antium who dismember Marcius at last. The rabble's wrath originates in these 'broken homes.'".

22 On doubleness and the rhetor, see Rebhorn 133-196.

23 "entre ces théâtres," "catalogue" "pur tableau des choses" (143).

24 The actual makeup and use of the places of the stage is a vexed and complicated issue in Shakespeare studies. On the one hand are those who argue that while the Renaissance stage was different from its medieval predecessor, it retained explicit places (locus and platea, for instance) for explicit presentational and representational purposes. On the other hand are those who argue that the Renaissance stage was completely different from its predecessor, and was therefore "placeless." On the former position, see Dillon 4-16, Hattaway 38-39, and Wickham 8-10; on the latter, see Bevington 8-15 and Beckerman 157-213.

25 "nouer les parentés, les ressemblances et les affinités . . . où s'entrecroisaient sans fin le langage et les choses" (68).