“A cypress, not a bosom, hides my heart”: Olivia’s Veiled Conversions

Amy L. Smith, Kalamazoo College, and Elizabeth Hodgson,

University of British Columbia

Amy.Smith@kzoo.edu

E.Hodgson@ubc.ca

Amy L. Smith and Elizabeth Hodgson. '“A cypress, not a bosom, hides my heart”: Olivia’s Veiled Conversions'. Early Modern Literary Studies 15.1 (2009-10). <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/15-1/olivveil.htm>.

Figure 1. (Click image for a higher-resolution version).

Figure 2. (Click image for a higher-resolution version).

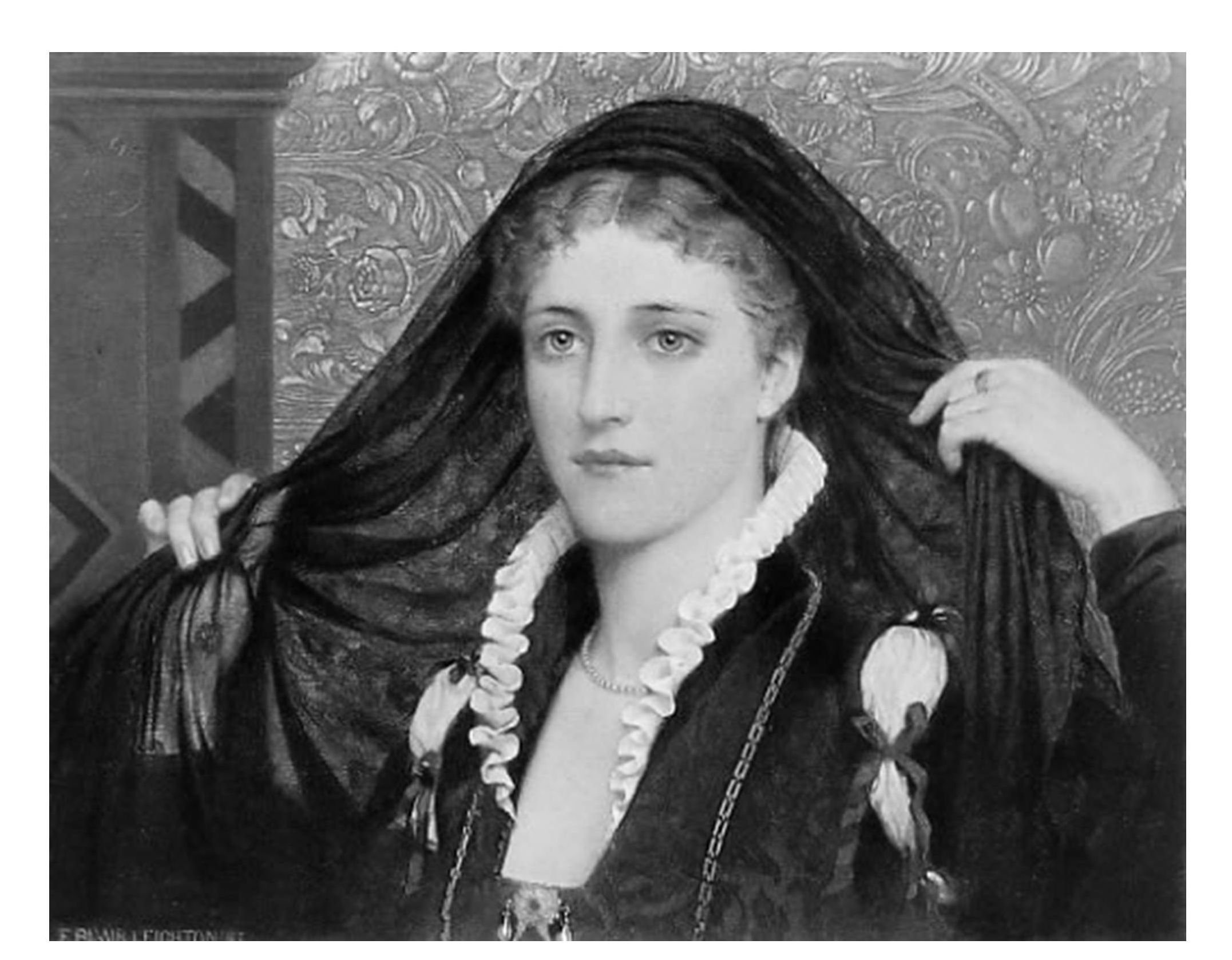

- These two late

eighteenth/early nineteenth-century artworks[1]

depicting Twelfth Night’s Olivia display Olivia’s self-concealment,

representing her veiling as an act rich with competing meanings. Edmund Blair

Leighton’s portrait (Fig. 1)[2]

makes visible the interpretive challenge Shakespeare’s character poses. In it,

Olivia stands in front of a gold brocade wall hanging; decorated in jewels to

suggest her economic independence, her hands pull back her black veil. Her

right hand, as well as the wall hanging, is visible through its fabric

(cypress?), both hidden and revealed. Olivia’s face is as solemn as her black

gown, but her gaze is direct and unconcealed. Her semi-disguise suggests both

her value and her autonomy.

- The engraving by

Thomas Ryder (Fig. 2)[3],

suggests another cultural reading of Olivia’s veiling. Ryder turns Olivia into

a sexual commodity, implying her seductive value through her flirtatious gaze.

While her hand rests on a skull (a memento mori of sorts), her veil is

white and flowing, as if to suggest a virginal maiden. Simultaneously, though,

her tightly corseted dress and slightly spread legs suggest a certain

uncontainable sexuality. A curtain is pulled back above her, revealing not

only the panoramic outdoor view of her garden, but also Olivia herself—she is

her own portrait.

- These turn of the twentieth century works reiterate particular

cultural notions of how female characters should be displayed or hidden, clothed

or unclothed. They also illustrate specific early modern anxieties about the

veiled woman, with her (in)visibility, her hidden sexuality, her social

containment or lack thereof, and her uneasy associations with mourning’s erotic

potential. While the Renaissance Englishwoman (nun, maiden, widow) is

repeatedly adjured to dress chastely, her very hiddenness and seclusion also

seem to make her a frequent object of intense suspicion and the subject of

excited amorous pursuit.

- This cultural

fascination with the veiled female face is evident in Vives’s popular conduct

book The Instruction of a Christen Woman[4]

which is replete with images (literal and metaphoric) of veiling: “She can

not be chaste that is not ashamed: for that is as a cover and a vaylle of her

face. For when nature had ordyned that our faces shulde be covered and that

for a great commendation, that who so dyd loke upon it shulde understande some

great vertue to be under that cover” (51). Veiling herself in shame is the

only way for a woman to assure onlookers of her chastity—virtue can exist only

under cover. Vives, however, is equally adamant that “going under cover” can

suggest only a lack of virtue: “Let women use no faynyng nor clokyng, to seme

good with all: nor let them nat think that they can cloke, or els change the

nature of things: the couterfete is not lyke the very thynge, the covered and

shadowed is feble and unsure, and shal be at laste open and knowen” (50).

Vives vacillates between the desire for women to be veiled and for them to be

uncloaked because he is caught in this ambivalent cultural ideology of la

femme couverte and la femme découverte.

- Given the

complex valences of a covered woman, it is not surprising that the veiled nun,

widow, or maiden is a common figure not only in conduct-books like Vives’s, but

also in early modern drama. This figure has subsequently been imagined much of

late in the critical realm.[5]

But her characterization (innocence and shame coexist even in the covered

woman) offers competing narratives that serve both to confirm and challenge her currency. This is particularly true in Twelfth

Night. All of the comedy’s deliberate plays with the sartorial markers of

widowhood and/or chaste seclusion suggest that Shakespeare’s drama appears to

be taking some issue with the fascinatingly contradictory cultural narrative of

untouchability, especially through the character of the Lady Olivia who is so

complicatedly marked as a veiled object of desire. For despite her

associations, Shakespeare’s Olivia avoids becoming either a representative of

the lusty widow as figured in multiple widow hunt dramas of the early

seventeenth century or the equally conventional chaste vowess of maidenhood;

rather, Twelfth Night engages in some quite

startling play of its own, making Olivia a nun, a widow, and a maiden in

ways which authorize her to veil and unveil her desires for economic and erotic

independence. When Olivia veils herself, her character invokes the power of

conventional seclusion for women of the period and the English past. When her

grief converts to amorous desire, but without the usual reprisals or subjection

to masculine authority, Shakespeare remakes the lusty-widow narrative. And

when she stage-manages her own marriage-choices, Shakespeare’s Olivia remodels

the economic exchange of maidenhood. In moving Olivia among these roles

without comment or narrative punishment, in replacing one veil with an

unveiling and then with another veiling and unveiling, Shakespeare makes Olivia

into a figure unexpectedly clothed with more than her picture might suggest.

I. The Nun

- Olivia is,

unlike Riche’s original Juliana,[6] a “virtuous maid” who “hath abjured the sight and

company of men” (1.2.36-7).[7]

Olivia’s seclusion thus involves an active withdrawal from the world of men—a

world where perhaps her status leaves her vulnerable. Her veiling, and her

seclusion, suggest to others in the play that she is a kind of “cloistress,”

not least because veiling was so clearly associated with nuns; the veil is

defined as a “a piece of linen or other material forming part of the

distinctive head-dress of a nun.” “To take the veil” is shorthand for to

“become a nun/ to enter a convent or nunnery” (OED). Taking the veil was

a material symbol of a spiritual and bodily change—“the transition of that body

from abject tissue to a clean and empty vessel to be filled with spiritual

power. To take the veil was, in a way, to disappear . . . [it] screens the

body from others and from itself, attempting to make it vanish from view.” [8]

Certainly some women did not take the veil of their own volition but were

pressured into monastic life as a way of “defending” family property against

the “fertility of excess daughters.”[9]

Such pressure is evinced by Theseus’s and Egeus’s view in A Midsummer Night’s

Dream: “yield . . . to your father’s choice, . . . or endure the livery of

a nun” (1.1), both choices implying subservience of the daughter’s fertility to

the father’s will (“yield” or “endure . . . livery”). As Margaret King

suggests, “nunneries fulfilled for prudently managed families, the role for

which they were intended: to house females for whom there was no other

convenient role.” [10]

In this scenario, nunneries provide women with a role chosen for them by male

relatives.

- This

“vanishing,” however, often seems beneficial to the women themselves. Hermia

certainly prefers chastity to a forced marriage:

Hermia deliberately confuses her “lords” (husband? father?), resisting them both in explicitly political language (“sovereignty”, “yield,” “patent”). She prefers not to be patent—shown or revealed—to whom she does not choose. Perhaps for Hermia, as for some of the early modern women King studies, the convents were, “of those settings available, the one most favorable to female autonomy.”[11] It is possible then to read veiling as a choice that allowed some women to remove themselves, to vanish from sexual circulation/marriage.[12] Veiling, like the cloistering it resonates with, implies “freedom not constraint.”[13] When Viola longs to “serve that lady” in her self-created convent, she too responds to this desire for private autonomy: “O that I . . . might not be delivered to the world / Till I had made mine own occasion mellow, / What my estate is!” (1.2). Viola, like her proposed mistress Olivia, seeks to delay and manage her “deliver[y] to the world.”So will I grow, so live, so die, my lord,

Ere I will yield my virgin patent up

Unto his lordship, whose unwished yoke

My soul consents not to give sovereignty. (1.1.79-82)

- Twelfth Night makes Olivia a rather unconventionally autonomous nun: her

seclusion is self-appointed, with a “terminus” of seven years rather than a

lifetime, in a lavishly appointed and rather unascetic convent. Much criticism

on Olivia suggests that her nun-like veiling is a passive “indifference to the

outside world”; her isolation, A.B. Taylor imagines, is that of a “bored,”

“proud,” “vain,” “self-centered” woman.[14]

This oddly and tellingly judgmental reading of Olivia’s character seems

deliberately to ignore the functional character of her veiled isolation, the

control Shakespeare allows this character over her relationship with the rather

obvious pressures of the outside world and the protection and autonomy he

grants her within it.

- Indeed, within

the context of veiling as an alternative to marriage—either through celibacy or

rule of one’s own household as a ‘widow’—Olivia’s veiled absence specifically

manages the many overt masculine attempts at “sovereignty” over her in the play.[15]

Clothing, Susan Vincent argues, could play a role in communicating one’s

desires: “The sartorial project, although begun in private, generated most

meaning when viewed by others”;[16]

Olivia’s veiling is just such a public “sartorial project” that specifically

allows her to limit Orsino’s access to her, and many of the descriptions of

Olivia’s isolation are aligned with her rejection of him. Tellingly, it is

when Orsino asks Valentine what news he has from Olivia that Olivia is

described as a nun:

The element itself till seven years’ heat

Shall not behold her face at ample view,

But like a cloistress she will veiled walk

And water once a day her chamber round

With eye-offending brine—all this to season

A brother’s dead love. (1.1.27-30) - This image of Olivia’s veiling suggests her

seclusion in a religious community, a cloistering which offers explicit

reprieve from her status as eligible single woman pursued by Orsino. Olivia

has managed to perform the role of a “veiled” “cloistress”—a role which

protects her chastity, isolating her from Orsino’s self-absorbed desires and

enclosing her in a cloister of her own making. And while the fool ironically

tells her that “cucullus non facit monachum” (1.5.48-9), in her case the

“cucullus” signals just that.

II. The Widow

- The image of Olivia seasoning “a dead

brother’s love” also suggests of course Olivia’s association with widowhood,

especially widowhood as a site where the “uncovered woman’s” sorrows and

desires intersect. The fascinating contradiction in the above passage between

Olivia’s “eye-offending” saltiness, which would wither her beauty, and the

“watering” of her sorrow, suggests that what she might “preserve” (her

brother’s memory, her own privacy and singleness) through salting is also her

means to remain “fresh” (“fresh in murmur”; “fresh in love”). Twelfth Night

as a whole is replete with the slippage between mourning and desire: when

Orsino thinks threnodies inspire desire (“Come away, come away death”); when

Viola emerges in clothes reminiscent of her brother’s (her own version of a

mourning garment perhaps) only to become “sick” for a beard—but not her

brother’s; when Feste’s love-song invokes the morbid carpe diem trope

(“youth’s a stuff will not endure”); when the romances are concluded with a

song about falling rain; and, most dramatically, when Olivia abandons her

veiled sorrow to choose her own love-object. Stephen Greenblatt, Valerie

Traub, Casey Charles and others have identified the malleability of desire

within the play in terms of hetero- or homosexual normativity (the “bias of nature”).[17] They

have charted the interchangeability of masculine and feminine love-objects in

the play and read these as either a challenge to or a restatement of

masculinist or heterosexual norms.[18]

But the play considers the malleability not of desire in a general sense but

specifically, as it engenders and is engendered by grief and mourning. The

gendered ideologies linking hiddenness, desire, and mourning in the play are

fundamental to the cultural work of Twelfth Night.

- It is in this

particular context that Olivia appears in the role of “lady widow.” Orsino

triggers this identity early in Twelfth Night with his fantasy of her

amorous grief:

Melancholy actually breeding desire is as major a dynamic in the play as Orsino’s own melancholic eroticism, filling the play with sorrow’s lusts and suggesting that Olivia is herself the paradigmatic figure of this Galenic mode, the lusty widow. Orsino’s phrase “debt of love” suggests both a widow’s debt to her dead husband (in this case “but a brother”) and a marriage debt to a subsequent husband, hinting at the link between past and future loves which was associated with widows.O, she that hath a heart of that fine frame

To pay this debt of love but to a brother,

How will she love when the rich golden shaft

Hath killed the flock of all affections else

That live in her . . . ? (1.1.32-6)

- Consider for

instance the fantastically popular “Widow of Ephesus” story, in which a tearful

widow locks herself in her husband’s tomb and vows to weep herself to death,

only to emerge a few days later as the lover to a soldier she meets in the

graveyard.[19]

The tale in medieval and Renaissance Europe was interpreted both as a

condemnation of the Widow’s extreme lust and, less frequently, as a

condemnation of her extreme grief-induced seclusion. The presence of such

divergent readings draws attention to the cultural complexity of Renaissance

ideals of widowhood that vacillated on the key issues of remarriage, chastity,

and marital availability. The overlapping of grief and desire, especially for

women, is captured vividly in one description of the Ephesian Widow: “that very

night in the morning of her passion, in the grave of her husband, in the pompes

of mourning, and in her funeral garments, [she] married her new and stranger Guest.”[20] The

“mourning” garments and the “morning” of her “pompes” and “passion” are

suggestively elided in this passage and in the cultural myth to which it

alludes.[21]

- Olivia, in her dress, her

seclusion, her disavowal of courtship, and her “uncovered” role as mistress of

her household and her fortunes, is in every sense recognizable as an exemplar

of the cultural archetype of the widow. Olivia in many respects is more a widow

than a mourner of a dead brother: she remains secluded and resists suitors as a

sign of her grief; she maintains authority over her domestic realm and her

dependents; she is the object of particularly conventional attempts at

consolation; and she is clearly equally concerned for her reputation, her

desires, and her estate. It is perhaps not surprising then that John

Manningham’s famous diary entry on a 1602 performance of Twelfth Night

suggests that Olivia’s veiling/mourning marked her as a widow, seeing “a good

practice in it to make the steward believe his lady-widow was in love with him.”[22]

Jennifer Panek suggests that “Manningham’s mistaken assumption that the maiden

heiress Olivia, in mourning for her brother, is in fact a remarrying widow

shows a mind already moving along paths that would become even more well

trodden over the next two decades.”[23]

Similarly, in Stephen Greenblatt’s reading, the mistake suggests that “the lady

richly left was a major male wish-fulfillment fantasy in a culture where the

pursuit of wealth through marriage was an avowed and reputable preoccupation.”[24] Olivia’s

widowhood, however, has cultural and dramatic registers beyond male fantasy.

The lady richly left is not only an object of desire, but also an independent

and desiring subject.[25]

- The empowering

seclusion of widowhood, within the house and within the protection of a widow’s

weeds, did occur to Shakespeare’s contemporaries. Early modern Venetian

printmaker and social commentator Cesare Vecellio describes how mourning-attire

itself can be a powerful tool: “They are always dressed in black. If they wish to

remarry, they may, without incurring blame, wear a few ornaments, and uncover

slightly their hair. This makes known their intentions to those who see them.”[26]

Veiling then, could offer women a means of control—it ironically makes the

mourning and the intentions of the wearer visible. Yet many scholars see

Olivia’s veiling as a mark of withdrawal from the social rather than a managing

of her appearance in it. Indeed, rather than seeing her as choosing this

“costume,” they clothe her in passivity, claiming that she merely fosters the

male “widow fantasy,” forswears men due to an impractical youthful idealism, or

is simply stuck in the role of grieving sister.[27] We

argue, though, that Shakespeare makes Olivia’s veiling (and unveiling) of

herself more calculated and performative. Susan Vincent suggests that such

calculations occurred in the culture itself:

For those women who continued in mourning garb after the funeral rites, their dress proclaimed their removal from normal society. Revealing their special status, it marked out a liminal time during which they were freed from the rules of polite social interaction. Widows in particular might use their mourning weeds as a way of permanently redefining their status, signaling their removal to a position independent of further marital transactions.[28]

The wearing of a mourning veil, like the wearing of a nun’s veil, provides a way to redefine a woman’s status and remove her from “marital transactions.”

- Writers like

Vives concur that mourning clothes mark a woman as unavailable: “Therefore let

them go covered and shewe in dede, what theyr name meaneth. For the name of

wyddowe in Greke and latine is as moche to say, as desolate and destitute”

(173). Yet wearing mourning clothes was also represented as rife with

emotional dangers, including hypocrisy and showiness (not wholly unlike Vives’s

concerns about “faynyng” and openness). Thomas Cartwright objects to wearing

mourning: “seeing therefore, if there be no sorrow, it is hypocritical to

pretend it, and if there be, it is very dangerous to provoke it, . . . it

appeareth that the use of this mourning apparel were much better laid away than

kept.”[29]

Women, the Separatist Henry Barrow implies, are especially susceptible to both

dangers because they care so deeply about fashion and “have their mourneries

fitted at an haire breadth.”[30]

Thus neither the wearing of mourning attire nor the eschewal of it frees women

from suspicion of hypocrisy, extreme emotion, or even the lusty widow

stereotype.

- Yet Twelfth

Night dwells less on the dangers (“What a plague means my niece to take the

death of her brother thus?” (1.3.1-2)) than on Olivia’s ability to negotiate

them—as not only a “widow” but also a “nun” and a maid who is alternately

covered and uncovered. Olivia maintains her single/eligible status as a

“virtuous maid” pursued by Orsino (“twas fresh in murmur . . . that he did seek

the love of fair Olivia” (1.2.28-30)) while she denies that role--as one who

“hath abjured the sight and company of men” for the love of her dead brother

(1.2.36-7). As Hunter suggests, “Olivia’s mourning . . . seems to be a sort of

theatrical game . . . Olivia ostentatiously mourns the death of her father and

brother, partly it seems to evade Orsino’s marriage proposal.”[31] This

curiously paradoxical “ostentatious” and “theatrical” game of veiled seclusion

is precisely what Shakepeare’s Olivia engages in.[32]

III. The Maiden

- Olivia is of

course also a very odd widow: one who is at the same time a distinctively

marriageable maiden. She has the amorous cachet and independence of both

roles, simultaneously and congruently. Judith M. Bennett and Amy Froide

suggest that as for wealthy widows, “among elites, it . . . seems that wealthy

heiresses who controlled their own destinies were better able than other women

to forgo marriage.”[33]

Shakespeare’s character’s uniquely virginal independence allows her to retain

single autonomy and negotiate the anxieties surrounding it. It is of interest

then with regard to Twelfth Night that Froide suggests that age and

social status allowed a small number of single women to achieve what she calls

widow-like status: “An older single woman who had neither a parent’s nor a

husband’s household to live in, may now have resembled a widow and like a widow

now had the privilege of living on her own.”[34]

If a single woman could achieve widow-like status, she would not be under male

control on the marriage market and could take her place as an independent head

of household. Such single women may have been able to attain a certain level

of social, economic and even sexual autonomy not usually available to them.

- As Shakespeare constructs Olivia, the ostensible reason for her

veiling and vows associates her with loss and death, making her into a widow of

sorts, but the veil—that which covers, protects, conceals—suggests that

Olivia’s choice has equally strong implications for her as an autonomous single

heiress. As the Widow of Ephesus story suggests, any mourning-costume could

mask desire as well as loss. If single heiresses were often vulnerable as

changing pieces on the marriage market, Olivia’s fatherless/brotherless

position seems to allow (perhaps require?) her to protect herself from

the Orsino match. In fact, Olivia’s veiling suggests a second performance of

sorts—one which allows her to play the role of a (virtual) nun/widow/Petrarchan

love object, preserving her chastity, her estate, and the use-value of her own

beauty in the process. In making Olivia a veiled single woman, Shakespeare

makes a character who chooses who can “negotiate with [her] face” (1.5.204).

- Olivia is

explicitly introduced through her role as marriageable maiden; she is first

“seen” in the play as veiled precisely from those who

would woo her. Sir Andrew tells Sir Toby, “Your niece will not be seen,

or if she be, it’s four to one she’ll none of me. The count Himself here hard

by woos her” (1.3.87-89). Both the betting language “four to one” and the

suggestion that the count “hard by woos her” suggest Olivia’s position as an

oddly private public commodity. Sir Andrew’s inability to see Olivia is

juxtaposed with Sir Toby’s “triangular manipulation for wealth, ease and power

through the exchange of the body of his niece.”[35] So

when Toby criticizes Olivia’s widow-like seclusion, “what a plague means my niece

to take the death of her brother thus?,” we see both her power to withhold and

his desire to trade on her value; it is ironically death to him (“a plague”) if

she refuses to be sold.

- Malvolio

likewise reveals Olivia’s complicated role as an unavailable and yet available

woman. While Malvolio often affirms Olivia’s position as head of her own

house, “My lady bade me tell you that although she harbours you on as her

kinsman, she’s nothing allied to your disorders,” perhaps because of the power

it gives him as her servant, he too serves as a reminder of just how marketable

she is (2.3.86-87). His desire for Olivia also rests on the exchange of her

body for wealth and status, an exchange which he tellingly figures in terms of

prestigious array: “Having been three months married to her, sitting in my

state . . . Calling my officers about me, in my branched velvet gown, having

come from a day-bed where I have left Olivia sleeping . . .” (2.5.39-44).

Malvolio here no longer reinforces Olivia’s status as head of household;

rather, he imagines himself as the usurper of her power and money—“my state,” “my

officers,” “my branched velvet gown.” His fantasied dress particularly

embodies “abstract signifiers of authority . . . [and] status in an intensely

material fashion.”[36]

It is also significant that Malvolio leaves Olivia behind as he gathers the

signs of her status around him; in his dream, he has taken her place as head of

household. In both cases, Olivia is perceived as an object of advancement

that will enable Malvolio to be cloaked in authority: “M.A.O.I. doth sway my

life”; “some have greatness thrust upon them” (2.5.100, 127). Here another

male character, like Toby, like Sir Andrew, and like Orsino, fantasizes about

sexual and economic control, but the play resists the fulfillment of such

fantasies by having them enacted by unsuccessful wooers. Rather than easing

cultural anxieties by representing Olivia as subject to such desires, it

represents her as capable of negotiating them through her enactments of

maidenhood. It is telling that Malvolio’s fantasies actually clothe him in

ridicule, both literally and metaphorically.[37]

- Orsino, a count in his own right, claims not to be drawn to Olivia’s

wealth:

Yet his attention to her “dirty lands,” his repeated use of the word “fortune” and his insistence on the nobility of his love, all focus our attention on her object-value. Indeed even in denying his interest in wealth, he commodifies her as “queen of gems" (2.4.83). Orsino’s language in act 1 scene 1 also suggests his desire to sexually (and economically?) dominate Olivia with his “golden shaft” and rule her emotions as a “king,” though her “affections” do not submit to him. He thus unconvincingly codes her economic independence as something of no interest to him while simultaneously objectifying her with it. Might he wish to wear her literal gems? Olivia, after all, frequently does offer such gifts, giving Viola/Cesario a ring and jeweled portrait, and Sebastian a pearl, distributing her wealth to whom she chooses.Tell her my love, more noble than the world,

Prizes not quantity of dirty lands.

The parts that fortune hath bestowed upon her

Tell her I hold as giddily as fortune. (2.4.79-82)

- Olivia is

objectified further by Orsino’s attempts to place her in the untouchable role

of his sonnet mistress “sovereign cruelty” (2.4.78). As René Girard suggests,

Orsino’s object is to make Olivia his “eternal

prisoner”[38] through his desire for her. Critics like Jami Ake

have suggested that it is not until Olivia meets Viola/Cesario that she is

freed from “her own scripted role as inaccessible sonnet mistress—one she has

seemed to passively accept."[39]

There is, however, evidence that Olivia’s acceptance of this role is more

active and socially motivated than such readings suggest. In fact, Toby claims

that status is key to Olivia’s decision not to allow Orsino access to her:

“She’ll none o’ th’ Count. She’ll not match above her degree, neither in

estate, years, nor wit; I have heard her swear’t” (1.2.105-7). Olivia seems

insistent not to marry up in status or age or even wit. Her inaccessibility

and “sovereign cruelty” allow her to maintain the sovereignty of her household.

- Indeed, Olivia

dons her veil specifically when Orsino’s messenger is announced: “Give me my

veil. Come, throw it o’er my face. / We’ll once more hear Orsino’s embassy,”

thus again linking her veiling with his wooing in particular (1.5.147-8). In

doing so, she also associates her face/identity with portraiture. And while

this might serve as evidence of Olivia’s static nature,[40] we

might also consider this veiling as another type of measured protection and

preservation. If as Cavallaro and Warwick argue, “the costumed body in

Renaissance England was a site of mediation between real life, the visual arts,

and the art of theatre,”[41]

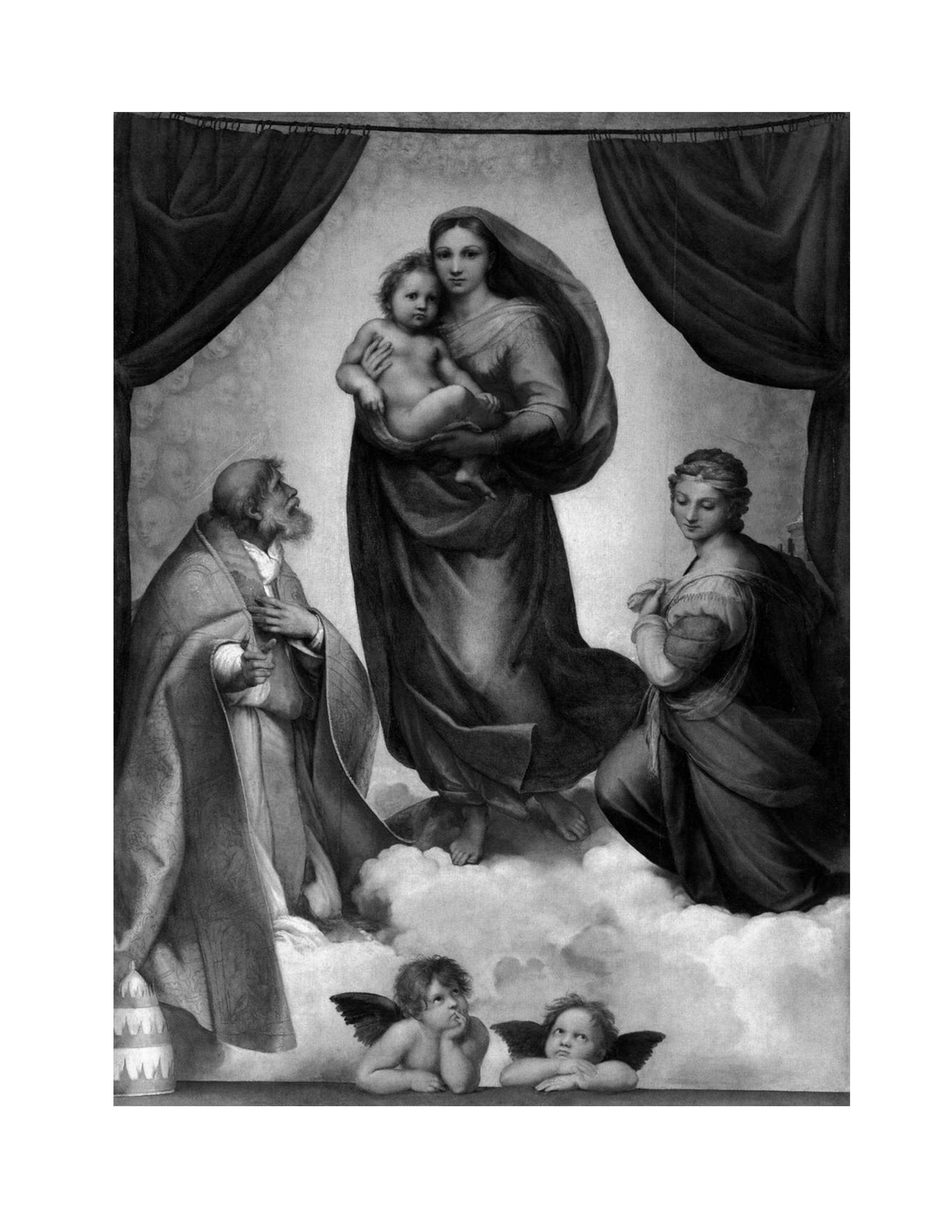

Olivia here is agent, portrait and actor.[42]

When Olivia says, “we will draw the curtain and show you the picture,” she

marks her face as a painting that veils or curtains were used to protect

(1.5.202-03). Olivia imitates Raphael’s “Sistine Madonna” which shows a veiled

Madonna as if the curtains had been pulled to either side to reveal her holding

the Christ Child (Fig. 3).[43]

This image suggests the symbolic weight of Olivia’s own self-revelation, a

weightiness echoed when Feste calls her “my lady . . . Madonna.” Here too,

Raphael and Shakespeare both play against commentators like Vives who insist

that virgins remain covered: “for that reason she is called alma in Hebrew,

which means ‘hidden virgin” and “vergin closed in” (113). Uncovering herself,

like the Madonna, Olivia reveals a sexual and economic subject.

- Olivia’s

unveiling also differs starkly from Cressida’s (Troilus and Cressida was

of course first performed in the same year as Twelfth Night). When

Pandarus presents Cressida to Troilus, he echoes the language of Olivia’s

unveiling: “Come, come what need you blush? Shame’s a baby. . . . Come draw

this curtain and let’s see your picture. [He unveils her] Alas the day!

How loath you are to offend daylight! An’t were dark, you’d close sooner”

(3.2.38-47). Here, though, Cressida is unveiled rather than unveiling herself,

and Cressida feels betrayed by her revelation: “Who shall be true to us, when

we are so unsecret to ourselves?” (3.2.213-14). Both Cressida’s veiling and

her unveiling are associated with shame and crudely lecherous jokes about hawk

taming and target-games; she is in effect undressed for sexual consumption when

she is unveiled.

- Viola attempts

to voice such masculinist protocols, picking up not only on Olivia’s

portrait/imprinting metaphors but also on the language of sexual ownership used

by Olivia’s other suitors: “If you are she you do usurp yourself, for what is

yours to bestow is not yours to reserve” (1.5.167-68), and then more forcefully:

Lady, you are the cruell’st she alive

If you will lead these graces to the grave

And leave the world no copy. (1.5.211-13) - That these moments center on Olivia’s unveiling

suggest a critique of her veiling. But if this veil is one that Olivia has

erected between herself and erotic overtures,[44]

it has given her great autonomy. When Viola/Cesario suggests that Olivia leave

the world a copy, meaning child, Olivia wittily reshapes the debate by taking

her to mean "inventory," actively reframing the procreative

metaphor. Viola’s plea for unveiling is too much like Sir Toby’s mocking

exhortation to Sir Andrew: “Wherefore are these things hid? Wherefore have

these gifts a curtain before ‘em? Are they like to take dust, like Mistress

Mall’s picture?” (1.3.105-07); echoing the ridiculous hardly makes Viola’s plea

more weighty. Sir Toby says to Sir Andrew, “Is it a world to hide virtues in?”

(1.3.110) and the right answer is of course, in Sir Andrew’s case, “Yes!” After

all, his “virtues” amount only to “kickshawses” and “caper[s]” (1.3.96,101).

If Viola/Cesario is to convince Olivia that the right answer in her case is

“No,” it will require quite a conversion, and one in which Olivia actively

participates.

- Even after

unveiling, Olivia wittily rejects the reproductive imperative by making her

face rather than a child her means of reproduction. She shifts Viola’s

Petrarchan insistence that the opposite of procreation is death by providing

her beauty as a living text which she will “impress,” one in which she is the

printer and the inventory (like the inventory of widows in their wills) that only she can bestow: “I will give out

divers schedules of my beauty. It shall be inventoried and every particle and

utensil labelled to my will, as, item, two lips, indifferent red; item,

two grey eyes, with lids to them; item one neck, one chin, and so forth”

(1.5.214-18). Her face thus becomes almost a veil itself—one which is another

cover, not an entrance to her subjectivity. She can only “usurp” herself, not

be usurped by others.[45]

- When she does

fall in love, she simply restructures her own conditions. Olivia has

previously veiled her face and “watered her room” over her dead brother, but

Viola/Cesario incites in her a similar kind of melancholy (which Maria notes).[46] She

shuts the garden door to all men so that she may mourn, but she later shuts

that same door so that she may have a private interlude with Viola/Cesario

(3.1.90). She declares her love-suit by confessing that “a cypress” hides her

heart, in a doubly ironic reference to her previous mourning and her newly

unveiled desire. Indeed, the fabric of cypress itself (often used for veils

and as an added layer over rich and beautiful fabrics) was known for its

ability to “lend [what lay underneath] a charm through partial concealment.”[47] Like

the Widow of Ephesus, Olivia woos her new lover in her mourning garments.

- This potential

betrayal of her brother and of the rules of feminine subjectivity is, however,

significantly mitigated in the play by the ubiquity of this humoural convention

of amorous sorrow. Because she is both widow and maiden, the continual play

on hidden spaces and faces (the “soul within the house,” the veiled painting,

the darkened room, the secret worm i’th’bud) in the text are all reminders of

the congruencies between Olivia’s widow-like mourning and the love-melancholy,

the solitude, the tears, and the masking, of her startling volte-face into

amorous desire. Shakespeare grants Olivia both a public and a private space

from which to reveal and conceal her desiring self. Outhwaite has argued that

what made single women an anomaly was not their rarity but rather what Ruth

Kelso has termed their lack of “social space or identity.”[48] What

seems most significant about Olivia’s shift to desire is that it does not

result in either the loss of her social space or her identity as the head of

her household. Nor is her desire strongly condemned. If the cultural fear of

transferred desire and the cultural anxiety over an unmanned woman coalesced

around the figure of the desirous widow (of Ephesus or of Illyria), such

anxieties are neither uniformly felt or supported in a text like Twelfth

Night. Shakespeare’s Olivia chooses her own seclusion, her own secrets,

and is paradoxically free to own the spaces she chooses. She has one brief

speech of rueful self-mockery, and some doubtful moments in her wooing, but her

newly unveiled desires are like those of all the other amorous characters in

the play.

- It’s clear how

striking Olivia’s autonomous social space is when it is compared to the veiled

Mariana’s in Measure for Measure. Mariana is initially discovered in

her house, “probably by drawing back a curtain,” and the boy’s song, not unlike

Feste’s, is melancholy, connecting desire with loss: “But my kisses bring again

bring again, / Seals of love, though sealed in vain, sealed in vain” (4.1.5-6).

Yet any representation of Mariana’s desires is subordinate to the play’s

insistence on the completion of her betrothal by trading her body “i’th’dark” (

4.1.40). When she appears veiled at the end of the play, what is emphasized is

her lack of a clear role rather than any negotiation of the liminal spaces

between maid, widow, and wife: “Why you are nothing then” (5.1.176 ). Mariana’s

veiling protects her during the unmasking of Angelo’s actions, but she

simultaneously uses it as a marker of subordination: “I will not show my face /

Until my husband bids me” (5.1.168-9). Only when Angelo commands, “Let’s see

thy face,” does Mariana unveil herself (5.1.200). It is Angelo’s desires that

are fulfilled (“This is the body / That . . . did supply thee at thy garden

house” (5.1.205-07)) and his dominance that is suggested by her unveiling.

- Olivia, in

contrast, unveils herself and begins actively wooing Viola/Cesario. She becomes

the Petrarchan seeker, giving Cesario his own “five-fold blazon” (1.5.297).

Nor should we ignore to whom she unveils herself or her methods of pursuit—both

of which suggest that Olivia seeks to maintain her social and economic autonomy

in this courtship.[49]

It is only when Olivia is assured of the messenger’s youth that she agrees to

see him. She inquires, “of what personage and years is he?” And Malvolio

assures her, “Not yet old enough for a man, nor young enough for a boy . . . .

[O]ne would think his mother’s milk were scarce out of him” (1.5.138-44).

Cesario/Viola’s precarious positioning between boy and man and his association

with mother’s milk suggest that Olivia’s autonomous position might be

maintained in an encounter with him. Olivia also assures herself of his

parentage, "Above my fortunes, yet my state is well” (1.5.248),

immediately offering her purse in recompense for his "service" and

later offering the wealth and status she can offer, “Fear not, Cesario, take

thy fortune up” (5.1.144), thus repeatedly placing herself in the superior

position of economic independence. She seems able to proceed because “the man”

is not actually “the master” (1.5.298).

- While Olivia’s

capacity to generate soldier-suitors who are semi-emasculated by their desires

for her is clear, the exaggerated comic effect of these suitors further

diffuses any cultural condemnation of her economically powerful and unmanned

status. Sir Andrew Aguecheek is the most obvious example of this with his

drooping sword, his inability to act, and his incapacity to “dally nicely with

words” to “make them wanton” (3.1.13-4). Like the soldier in the Widow of

Ephesus tale, he attempts to follow protocol and woo the maid as a preliminary

to the mistress, but Maria, not he, is the sexual aggressor, Mistress Accost

who “leads him to the butt’ry bar” (1.3.40,66). Sir Toby encourages him to

perform a manhood he knows him not to have: “swear horrible, for . . . a

terrible oath . . . gives manhood more approbation than ever proof itself would

have earned him” (3.4.173-5). He is a “virago,” according to Toby (3.4.265),

and in his duel with Viola, their comically matched lack of masculinity

indicates just how feminized Sir Andrew himself has become.

- Sebastian, whose masculinity may seem less subvertable than Sir

Andrew’s, is introduced in a state of mourning that associates him with womanly

grief: “I am yet so near the manners of my mother that upon the least occasion

more mine eyes will tell tales of me” (2.1.34-6). Like Olivia, he is drowning

the remembrance of his sibling with “salt water” (2.1). Later, Sebastian is

likewise rendered “both a man and a maid” in his dealings with Olivia.[50]

Olivia says to him, at their first meeting, “Go with me to my house, . . . thou

shalt not choose but go” (4.1.52,55), and Sebastian willingly complies. Olivia

wishes him to “be ruled” by her, and he is, uttering a version of the

marriage-vows before the priest has even been mentioned: “Madam, I will”

(4.1.63). Olivia describes their marriage as “this act of mine” (4.3.35), and

it would be hard to disagree with her. Certainly Sebastian does not.

- Olivia and

Sebastian’s marriage resignifies the supposedly conservative roles of early

modern marriage. The wooing comes solely from Olivia, and while her "forwardness"

surprises Sebastian, he also seems attracted to her status and power, to her

ability to “sway her house, command her followers, / Take and give back affairs

and their dispatch” (4.3.17-9). By bringing together a powerful and propertied

woman of high status and a recently shipwrecked man currently without

resources, this wooing questions marriage’s function as an institution which

places men as the head of the household with their wives firmly beneath them.

- What is

crucially distinctive about Twelfth Night’s Olivia, though, is that

unlike other Shakespearean comic heroines, she does not lose her voice after

marriage. She continues to command “Cesario,” to rule as judge in Malvolio’s

grievance and to assure Orsino that the double marriage ceremony shall be “here

at my house and at my proper cost” (5.1.308). “The Lady Olivia has no folly,”

says Feste, as a testament to her power; he goes on to explain mockingly that

“she will keep no fool, sir, till she be married” (3.1.33-4), as if she will own or “keep” her husband, rather

than be kept by him.

- The betrothal ceremony itself

further highlights Olivia’s agency and reinforces her powerful social status.

Her description of it emphasizes her role in bringing about the marriage and

shaping the ceremony:

Now go with me and with this holy man

Into the chantry by . . . .

Plight me the full assurance of your faith

That my most jealous and too doubtful soul

May live at peace. He shall conceal it

Whiles you are willing it shall come to note,

What time we will our celebration keep

According to my birth . . . (4.3.22-35) - Olivia proposes the

betrothal ceremony, orders a priest, chooses its secret location (a chapel on

her grounds), requires that Sebastian pledge to her the “full assurance” of his

faith so that she can “live at peace,” proposes that when they publicly

celebrate their marriage it will be according to her birth, and, finally,

declares it her act. This betrothal speech by Olivia instigates the wedding

ceremony performed by a priest. Early modern wedding ceremonies are often

viewed as a ritualized containment of women, but this one is initiated to

resignify the purpose of such a ceremony, highlighting its satisfaction of

Olivia’s needs and desires and her manipulation and control of the desires of

others. She reinvents her own chosen cloistering; now she will go to the

chantry knowing that the priest will keep not her face but her new status

“concealed” at her command.

- All of the

critical arguments which read Olivia’s marriage as a re-containment of her

independent energies, either as the fulfillment of male economic fantasy or as

a correction of her transgressive homoeroticism, fail to recognize the extent

to which Olivia is allowed to remain the mistress of the play. Nor does Twelfth

Night take the route of so many widow-hunt plays and turn Olivia into a

man-hunter, the widow-tyrant;[51]

her power and her value appear equally great and equally undisguised—she is

“madonna” and “princess” (5.1.297-8) in the play’s final moments, and alliances

with her are welcomed by Viola, her new “sister,” and the duke himself. She

does not betray the rich widow’s proverbially “perverse and crabbed nature”

(125-6),[52]

and the play mocks not Sebastian for his loss of power but only Malvolio for

his overt fantasies of control.

- The character Olivia thus enacts a marriage which retains much of her single autonomy—unveiled but “confirmed by mutual joinder,” she has rejected the marriage market in which multiple suitors sought to usurp her status/money for themselves. Olivia’s marriage is “her act” in accordance with her estate, and she will, it seems, continue to dress herself in power. Indeed, the suitor to whom she unveils herself enjoys his passivity: “Let fancy still my sense in Lethe steep. / If it be thus to dream, still let me sleep” (4.1.58-9). What this waking dream allows the audience to imagine is not only the stock fantasy of male enrichment but also a reinvestigation of the veiled woman. Twelfth Night’s Olivia reveals (while she hides) a complex negotiation of the economic and sexual anxieties surrounding single maidens, widows, nuns, and even wives. The play allows Sebastian to “take up [his] fortunes” and Olivia to continue to “sway her house.” We can only imagine what she’ll wear to the wedding.

Notes

1 According to Laurie Osborne, there are, in fact, “several dozen engravings done in the nineteenth century to record Olivia’s relationship to Viola. . . . [The] moment when Olivia unveils is the most often represented.” “Intermingling illustration and text: hyper-illuminated criticism of Shakespeare’s works,” <http://www.colby.edu/personal/l/leosborn/illumin.html>, no date.

2 Edmund Blair Leighton (1853-1922) was commissioned by the Graphic magazine to produce this painting of Olivia as part of a series of portraits of Shakespearean heroines by several well-known artists of the time. According to Georgianna Ziegler, “The paintings were displayed in a London gallery around 1888 and reproduced as double-page centerfolds purchased with the magazine. They were also sold in portfolio editions that could be viewed on a table or individually framed.” (Georgianna Ziegler, Frances E. Dolan and Jeanne Addison Roberts. Shakespeare’s Unruly Women (Washington, D.C.: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1997), 32. The portfolio editions were published as The Graphic Gallery of Shakespeare’s Heroines.

3 Thomas Ryder produced his engraving of Johann Heinrich Ramberg’s painting of “Olivia, Maria, and Malvolio,” which was commissioned by John Boydell as part of his project to “publish a National edition of Shakespeare, illustrated by the first artists of the country.” (Josiah Boydell, Preface to the Original Edition, in The Gallery of Illustrations for Shakespeare’s Dramatic Works Originally Projected and Published by John Boydell, Ed. J. Parker Norris (Philadelphia: Gebbie and Barrie, 1874) v. The engravings were published in Boydell’s 1802 Dramatic Works of Shakspeare and 1803 Collection of Prints, from Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare.

4 Juan Luis Vives, The Instruction of a Christen Woman, ed. Virginia Walcott Beauchamp et al. (Chicago: U of Illinois P, 2002). This edition uses Richard Hyrde’s sixteenth-century translation of Vives’s Latin work. All Vives citations are from this edition and will be cited parenthetically in the text. Jennifer Panek argues that Vives is “not English” (9) and therefore not as relevant a source for English culture. Widows and Suitors in Early Modern English Comedy (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004). We would argue, though, that the fact that his Instruction of a Christen Woman was written for an English queen and published in several editions in England through the sixteenth century suggests otherwise.

5 See for instance Barbara J. Todd, “The Virtuous Widow in Protestant England,” Widowhood in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, eds. Sandra Cavallo & Lyndan Warner (Harlow: Longman, 1999), 66-84; Jennifer Panek, “‘My Naked Weapon’: Male Anxiety and the Violent Courtship of the Jacobean Stage Widow,” Comparative Drama 34, no. 3 (2000); Judith M. Bennett, “Widows in the Medieval English Countryside,” Upon my Husband’s Death: Widows in the Literature and Histories of Medieval Europe, ed. Louise Mirrer (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1992), 69-115; Widowhood in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Sandra Cavallo & Lyndan Warner ( Harlow, Essex: Pearson, 1999). Kathryn Jacobs, Marriage Contracts from Chaucer to the Renaissance Stage (Gainesville: U of Florida P, 2001); Jennifer Panek, Widows and Suitors in Early Modern English Comedy (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004).

6 See “Of Apolonius and Silla,” in Thomas Riche, Riche His Farewell to Militarie Profession (1581), Ed. Thomas Mabry Cranfill (Austin: U of Texas P, 1959), 74-78.

7 William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night or What you Will, in The Norton Shakespeare, ed. Stephen Greenblatt (New York: Norton, 1997). All Shakespeare citations are from this edition and will be cited parenthetically in the text.

8 Dani Cavallaro and Alexandra Warwick, Fashioning the Frame: Boundaries, Dress, and the Body (Oxford: Berg, 1998), 7.

9 Margaret L. King, Women of the Renaissance (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1991) 83.

12 King gives Francesco Barbaro’s daughters as an example of women who seem to have been using the convent to avoid marriage: “No shortage of funds could explain the rejection of marriage opportunities by three of four daughters . . . . Costanza (the eldest daughter), at least, and likely her two sisters as well, were nuns by choice” (96).

14 A.B. Taylor, “Shakespeare Rewriting Ovid: Olivia’s Interview with Viola and the Narcissus Myth,” Shakespeare Survey 50 (1997): 81-9, 82, 88.

15 Jonathan Crewe argues that “extended mourning for [Olivia’s] brother may well be a convenient way to keep decorous control over her unruly household and keep unwanted suitors at bay.” “In the Field of Dreams: Transvestism in Twelfth Night and The Crying Game,” Representations 50 (1995): 101-121, 105.

16 Susan Vincent, Dressing the Elite (Oxford: Berg, 2003), 9.

17 Stephen Greenblatt, Shakespearean Negotiations: The Circulation of Social Energy in Renaissance England. (Berkley: U of California P, 1988); Valerie Traub, Desire and Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakespearean Drama (London: Routledge, 1992); Casey Charles, “Gender Trouble in Twelfth Night,” Theatre Journal 49.2 (1997): 121-42.

18 Lorna Hutson offers a powerful critique of the Traub/Greenblatt turn, though she also imagines it impossible for a character like Olivia to be sexually independent, given how “in sixteenth century society, a woman’s sexual behavior was perceived to affect the honor and therefore the ecred and economic power of her kinsmen” (146). Hutson argues that Shakespeare “displac[es] deep into his depiction of female ‘character’ . . . an inclination toward sexual betrayal” (151). "On Not Being Deceived: Rhetoric and the Body in Twelfth Night," Texas Studies in Literature and Language 38:2 (1996): 140-74.

19 The Ephesian Widow story was taught to European schoolchildren from Caxton on through the Stuart era. The classical fable was also reworked in a wide array of French and Italian romances and novellas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and included in the popular Seven Sages collections in Latin, French, and English, among other languages, which date back to 1493 and appear in ballad-form, in editions annotated by Erasmus, and in James I’s schoolbooks. Hans R. Runte, J. Keith Wikley, Anthony J. Farrell, eds., The Seven Sages of Rome and the Book of Sinbad: An Analytical Bibliography (New York: Garland, 1984) 38ff.; Johanna H. Stuckey, “Petronius the ‘Ancient’: His Reputation and Influence in Seventeenth Century England,” Rivista di Studi Crociani 20 (1972): 145-53. Vernacular versions of the Ephesian Widow story date back to Caxton, forward to lost play-texts by Dekker in 1600, and on through the seventeenth century, with the first English translation of the Satyricon appearing in 1694. Hans R. Runte, “Translatio Viduae: The Matron of Ephesus in Four Languages,” RLA: Romance Languages Annual 9 (1997):114; Runte, Wikley, Farrell, Seven Sages; Gaselee, “Bibliography of Petronius,” 180–1.

20 Shakespeare’s transformation of Olivia in particular from “widow” to wooer is far more restrained in certain respects than of Juliana (in Riche’s story) or of the Ephesian Widow. Olivia’s sexual morality is more correctly conventional, in particular. Her rapid shift from sorrow to amorous desire, alongside her function as a master-mistress, though, mark her affiliations with the figure of the lusty widow.

21 Many readings of Twelfth Night debate the extent to which it is just such an enacted cultural “fantasy.” “In the current text-critical literature, we seem to be told both that these are texts of sexual fantasy, disturbing and transgressive, and that these texts record some ‘actual’ possibility for individualized, subversive affirmation of sexuality” (28). Lisa Jardine, “Twins and Travesties: Gender, Dependency, and Sexual Availability in Twelfth Night,” Erotic Politics: Desire on the Renaissance Stage, ed. Susan Zimmerman (New York: Routledge, 1992) 27-38. Historians of widowhood, for example, often try to discern the slippage between the fantasies of widowhood prevalent in particular cultures and the lived experience of widows, as if those are distinct categories. More sophisticated analyses study how such narratives are continually remade, whether in public texts or in private records.

22 Bruce R. Smith, Introduction, Twelfth Night: Texts and Contexts (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001). Manningham is attentive to clothing throughout his diary and his “mistake” is revealing.

25 See Kathryn Jacobs, Marriage Contracts from Chaucer to the Renaissance Stage (Gainesville: U of Florida P, 2001) who argues that Olivia is more widow-like and her independence greater than other Shakespearean heroines like Portia whose vows to a dead father limit her freedom. She also argues that perhaps early modern audiences “were more accustomed to seeing independent widows around them than independent virgins” (155).

26 Cesare Vecellio's Degli abiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo (1590). Qtd. in H. K. Morse, Elizabethan Pageantry: A Pictorial survey of Costume and its Commentators from 1560-1620 (New York: Benjamin Blom, 1934) 118.

27 See Dianne Hunter’s ”Shakespeare’s Continuity through the Daughter,” Literature and Psychology 48:3 (2002), 38-55; Jon S. Lawry, “Twelfth Night and ‘Salt Waves Fresh in Love,” Shakespeare Studies (1972), 89-108; John Hollander, “Twelfth Night and the Morality of Indulgence,” Twentieth century Interpretations of “Twelfth Night,”ed. Walter N. King (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1968), 79.

32 Douglas H. Parker makes a similar argument: “Her vow of seven years’ mourning is as much an attempt to discourage Orsino’s love pleas as it is an outward sign of grief” (25). “Shakespeare’s Female Twins in Twelfth Night: In Defense of Olivia,” English Studies in Canada 13:1 (1987): 23-31.

33 Judith M. Bennet and Amy M. Froide, “A Singular Past,” Singlewomen in the European Past, 1250-1800, ed. Bennett and Froide (Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1999): 1-37, 6.

34 Amy M. Froide, “Marital Status as a Category of Difference. Singlewomen and Widows in Early Modern England,” Singlewomen in the European Past, 1250-1800. 236-69, 242.

37 In the Trevor Nunn film, Malvolio even loses his toupée by the end—a final unveiling of his own. Twelfth Night: Or What You Will, dir. Trevor Nunn, Renaissance Films, 1996.

38 René Girard, “‘Tis Not so Sweet as it was Before’: Orsino and Olivia in Twelfth Night,” Stanford Literature Review 7 (1990): 123-32, 131.

39 Jami Ake, “Glimpsing a ‘Lesbian’ Poetics in Twelfth Night,” Studies in English Literature 43 (2003): 375-94, 2.

40 A. B. Taylor offers a reading of Olivia’s static nature here, aligning Shakespeare with Cesario/Viola’s call to procreation and Olivia’s refusal with death: “. . . it is in ‘warm life’ that salvation lies, not in any ‘poor image’ or ‘cold stone,’ or ‘curtained’ ‘oily painting’. . . . Olivia’s catalogue has an immediate air of death about it” (84). Taylor’s remarks echo Sir Toby’s acquisitive view of female sexuality. Likewise Edmund M. Taft argues that Olivia must be liberated from her “cloister” to achieve sexual health. “Love and Death in Twelfth Night,” Iowa State Journal of Research 60 (1986): 407-16, 407.

42 Olivia again associates herself with portraiture when she gives Cesario a miniature portrait, actively offering an image of herself (albeit a silent one): “Here wear this jewel for me, ‘tis my picture--/ Refuse it not, it hath no tongue to vex you” (3.4.184-85).

43 The formality and symmetry of Edmund Blair Leighton’s portrait (Fig. 1) echoes the solemn symmetry of the Sistine Madonna. Many arguments have been made about the significance of the curtain in that painting but it seems surely to have been related to the curtain that symbolized God, then Christ, then the Madonna as the vessel of Christ.

44 See David Schalkwyk, “‘She never told her love’: Embodiment, Textuality, and Silence in Shakespeare’s Sonnets and Plays,” Shakespeare Quarterly 45 (1994): 381-407 who argues that it is Cesario/Viola’s “fearlessness in her allotted role which breaks through the veil, literal and metaphorical, that Olivia has erected between herself and erotic overtures” (393).

45 Jami Ake interestingly argues that Viola creates a pastoral space in her “willow cabin” speech which provides Olivia “with the linguistic material with which to conceive of her own role differently—as more initiatory, more erotic” (384).

46 Jonathan Goldberg suggests that Olivia’s comment “ourselves we do not owe” refers even more aptly to Viola than to Olivia herself. “Textual Properties,” Shakespeare Quarterly 37 (1986): 213-17, 216.

47 M. Channing Linthicum, Costume in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries (New York: Russell and Russell, 1963). This contrasts the other use of the word "cypress" in the play which appears in Feste’s song, “Come away, come away death, / And in sad cypress let me be laid” (2.4.52-3). Here, the cypress is a cypress wood coffin. Cypress is still emblematic of mourning, but here it completely encloses the would-be mourner. Desire leads to thoughts of death rather than thoughts of mourning leading to desire. Orsino’s lover’s melancholy thus seems more stultifying than Olivia’s.

48 Ed. R.B. Outhwaite. Marriage and Society: Studies in the Social History of Marriage (New York: St. Martin's P, 1982).

49 Jean Howard argues that Olivia is “a figure whose sexual and economic independence is ironically reined in by means of the cross-dressed Viola” (431), despite the evidence that Olivia seems at least as autonomous at the end of the play as she does at the beginning. “Crossdressing, The Theatre, and Gender Struggle in Early Modern England,” Shakespeare Quarterly 39 (1988): 418-40.

50 Panek argues that this is a typical risk for the fortune-hunter husband: that he is “reduced to the traditional status of a wife” (56) in relation to the father/widow he has married. If this is the case, Sebastian and the play both seem unconcerned. Perhaps if Olivia cannot be pinned down, neither can Sebastian.

51 See Jennifer Panek’s intelligent discussion of this dramatic convention (Chapter 2 in her Widows and Suitors in Early Modern English Comedy).