"Paradise Lost": Epic and Opera

"Paradise Lost": Epic and Opera

P. G. Stanwood

University of British Columbia

stap@shaw.ca

P. G. Stanwood, '"Paradise Lost”: Epic and Opera'. [EMLS 15.3 (2011): 5]. http://purl.org/emls/15-3/stanpl2.htm

1. John Milton's great epic poem cannot be easily summarized nor conveniently reduced to a simple description. The twelve books of the familiar 1674, or second edition of the poem, comprise 10, 565 lines, by no means the longest poem in English—Spenser's Faerie Queene (1590, 1596), or Joseph Beaumont's Psyche (1648), or a number of Victorian epics, all are longer. Of course, Milton's poem is not brief, yet it is paradoxically both vastly capacious and fiercely concise. It is about good and evil; life and death; innocence and experience; joy and sorrow; love and hate; and many more similarly expressive and contrasting pairs.

2. Paradise Lost is often simply described in such terms. Although inadequate, they all possess enormous implications with the possibility of different emphases. Milton, as we know, had sketched various biblical dramas, including "Adam Unparadized," in the Trinity manuscript as early as 1640. Such considerations were eventually to become realized in the great drama of the Fall of Man within the grand divine plan of creation and salvation.

3. There have been many literary imitations, and countless allusions to Milton's works, especially Paradise Lost, and also a host of musical references and adaptations of his epic, such as Gasparo Spontini's Milton (1804). Concerning the history of musical translations (or transformations) of this work, Stella Revard writes that we do indeed learn much about the popular image of Paradise Lost in different ages: "For in adapting Milton's poem, composers and librettists have not only transferred it to a different artistic medium, they have rewritten and reshaped it to conform to the theatrical and musical tastes of their own eras."[1] Different parts of Milton's poem have appealed to different audiences: the creation, the councils of Satan, of God and the Son, the temptation and Fall, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise. And at the same time, Milton's moral purpose has been variously interpreted.

4. We may begin with Dryden's "State of Innocence" of 1673 (though never, in fact, set to music), remember especially Haydn's "Creation" (1798), based on a back translation of lines from book 7, then think ahead. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, three composers, moved by the great themes of Milton's poem, attempted settings of it in near operatic form: Anton Rubenstein (1829-1894) composed Das verlorene Paradies (1875); Theodore Du Bois (1837-1924) wrote Le Paradis Perdu (1878); and Marco Enrico Bossi (1861-1925) Il Paradiso Perduto (1903). It is unlikely that these composers—German, French, and Italian—were influenced by one another; but their aims were similar. While giving little attention to Milton's language or his plot, they all aimed to produce a large and spectacular effect, in musical design and scenic magnitude reminiscent of Berlioz or Meyerbeer. Satan figures prominently in these works whose struggle with the Almighty and the celestial beings results in the relative displacement of Adam and Eve and the human drama.

5. There continues to be interest in Milton's epic, with many contemporary glances, such as Eric Whitacre's unusual Paradise Lost: Shadows and Wings ("One Angel who followed her heart"), an electronically enhanced musical production, first offered in the summer of 2007 in Pasadena and Los Angeles. One serious attempt to interpret Paradise Lost is Phillip Rhodes's opera-oratorio of 1972, produced in Louisville, Kentucky. But by far the fullest and most important contemporary operatic treatment of the epic is that of Krzysztof Penderecki (b. 1933),[2] who uses material from all twelve books of Paradise Lost in his three-hour score. Penderecki's version of Paradise Lost, which he calls a Sacra Rappresentazione—a nod to the late Renaissance form, eminently achieved by Emilio de' Cavalieri in 1600—is based on the libretto by the dramatist and poet Christopher Fry (1907-2005), in forty-two scenes. The work faithfully reflects Milton, rarely departing from the poetry itself, but reorders and emphasizes many of the episodes for theatrical and special effect.

6. Penderecki is one of the world's greatest living composers. When the Lyric Opera of Chicago commissioned him to compose a work to help celebrate the American bicentennial in 1976, he was already well known for his avant garde sonoristic works, notably Threnody (1960) for fifty-two strings, dedicated to "the victims of Hiroshima." Other compositions for strings, orchestra, and oratorio followed, especially the St. Luke Passion (1965), and soon after his first opera, Die Teufel von Loudun (The Devils of Loudun) (1969), and Symphony No. 1 (1973). Penderecki's work has developed through several stages, from the early experiments with sound and notation, to an increasingly traditional musical idiom.

7. Schönberg, Honegger, and above all Messiaen offer important connections to Penderecki's work, but Paradise Lost is uniquely expressive. There is a distinctive harmonic structure and a melodic line where instrumental and vocal forces combine dramatically to tell the story of salvation. Now Penderecki pours out streams of melismatic cantilena, and he provides hymn-like passages of recitative, giving to the different characters decided effects: there are recurrent intervals—for Eve, the minor third, for Satan the tritone, for Adam both intervals. When God speaks, he is accompanied by the orchestra in octaves. And the principal characters are associated with certain orchestral timbres: Adam with strings, Eve with woodwind, Satan with brass, Sin with cor anglais and bass clarinet, Death with castanets. Sometimes the explosive rhythms recall Stravinsky mediated through Carl Orff. Nor does Penderecki eschew the occasional quotation from such melodic and traditional sources as Bach, with a chorale from the St. John Passion that occurs at the appearance of the Messiah, who brings comfort to the downcast Adam, near the end of the opera.

8. Penderecki was fortunate in his librettist, for Christopher Fry, who, with T. S. Eliot, attempted the revival of verse drama in the mid-twentieth century, is sensitive to the dramatic qualities of Milton's epic.[3] He manages to retain much of the poetry, though often truncating the pentametre lines, and occasionally paraphrasing and reducing whole verse paragraphs. Eve's last and great speech (book 12:610-23), for example, which Milton has cast as a kind of sonnet, Fry has radically trimmed. "Whence thou return'st, and whither went'st, I know," she says to Adam, who is returning with Michael from the hill where the archangel has displayed before Adam the visions of mankind's future. Eve continues,

For God is also in sleep, and Dreams advise,

Which he hath sent propitious, some great good

Presaging, since with sorrow and heart's distress

Wearied I fell asleep: but now lead on;

In mee is no delay; with thee to go,

Is to stay here; without thee here to stay,

Is to go hence unwilling; thou to mee

Art all things under Heav'n, all places thou,

Who for my wilful crime art banisht hence.

This further consolation yet secure

I carry hence; though all by mee is lost,

Such favour I unworthy am voutsaf't,

By mee the Promis'd Seed shall all restore.

Fry reduces this subtle speech, letting Eve say first to Michael: "Lead on: / In me is no delay." And then to Adam, "With you to go / Is to stay here. / You to me are all things under Heaven." The gentle evocation of reciprocity, and the anticipation of the second Eve and her Son is lost. Similarly, the final chorus is triumphant rather than reflective. Fry's paraphrase evidently suited Penderecki's purpose. The chorus sings:

The World is all before them,

Where to choose

Their place of rest,

And Providence their guide.

Through the world's wilderness

Long wanders man,

Until he shall hear and learn

The secret power

Of harmony, in whose image he was made.

Fry somewhat misses Milton's point, for Milton concludes:

Some natural tears they dropp'd, but wip'd them soon;

The World was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence thir guide:

They hand in hand with wand'ring steps and slow,

Through Eden took thir solitary way. (645-49)

9. "Long wanders man" generally expresses Penderecki's pessimism—akin perhaps to Berg's Wozzeck—and fundamental to this opera, and certainly to its immediate predecessor, The Devils of Loudun. In reviewing his career and work, Penderecki wrote in 1998 that "I am tempted by both the sacrum and the profanum, God and the devil, the sublime and its violation."[4] Penderecki's conception of Paradise Lost seems to rest on both these poles, yet to some extent he misses the fundamental optimism of the epic and the wonderful victory of God's Providential love, something that Milton expresses not only through God's speeches in book 3, but in the glorious and redemptive triumph of his Son, the theme of book 6 and later. But in the opera, the Son appears abruptly, almost an afterthought, as "Messias," and then quite briefly near the end of Act 2. Penderecki's opera is, nevertheless, an impressive achievement, and many of its scenes are both sung and danced. Adam and Eve have doubles who mimetically express their creation, their love, and their fall.

10. Paradise Lost has had four productions, with its premiere in Chicago in November 1978, with subsequent performances of that production in Milan. A second major production was mounted in Stuttgart in April 1979, with tours to Munich and other European opera houses; and a third, reduced production occurred in 2001, in Münster—the German productions being performed in a German translation of Fry by Hans Wollschläger (d. 2007, the translator of Joyce's Ulysses). Finally, a fresh production was mounted in the renovated opera house in Breslau by Opera Wroclawska for the season 2009-10. A selection of images from the Chicago and Stuttgart productions, with accompanying excerpts of eleven musical episodes selected from across the whole work may help us to imagine the theatrical and dramatic power not only of Penderecki but of Milton.[5]

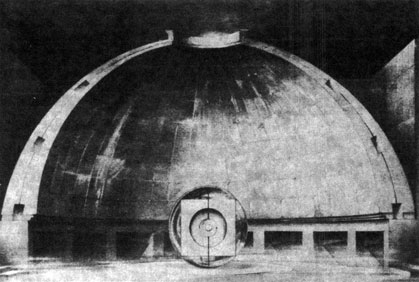

11. The opera opens with Milton's speech, adapted from the invocations of books 3 and 1 of the epic, while the Chicago production shows a massive dome that will shortly open to reveal the various scenes (audio 1, illus. 1).

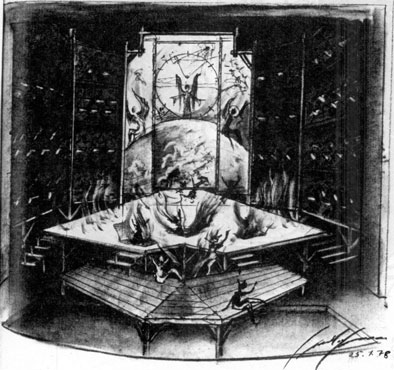

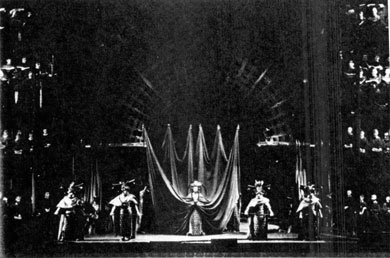

Satan's first speech to the fallen angels follows (audio 2, illus. 2 and 3).

This is interrupted by God's voice, an interpolation from book 7 of Milton's epic (audio 3).

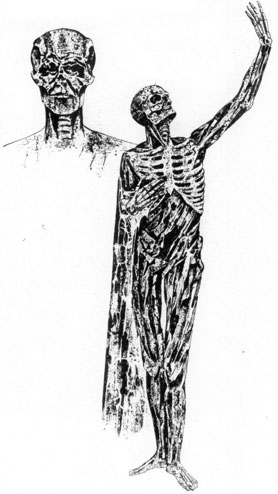

After "the great consult," Satan approaches Hell's gate (audio 4, illus. 4 and 5).

Meanwhile, in Paradise, Eve describes her unsettling dream (book 5.28-93), which closes Act 1 of the opera (audio 5).

Satan of course continues his watch in Paradise, seeking the best opportunity for seducing Eve (illus. 6a, 6b and 7).

The temptation and the eating of the forbidden fruit is depicted in music of great dramatic intensity, near the beginning of Act 2 (audio 6).

Having accomplished his goal, Satan returns to Hell (audio 7); Adam and Eve offer contrition and prayer (audio 8).

Most of Michael's instructive visions of the future (related in books 11 and 12) are collapsed into brief concluding scenes, and the last speeches of Adam and Eve, as previously discussed, are cast into cogent but highly abbreviated form. The opera ends with thick orchestration, on a triumphant D major (audio 9, 10, and 11; illus. 8).

12. Obviously, Fry and Penderecki have reordered many events of the poem, with the invocation to book 3 forming the opening lines, with comments by the chorus, then the lines that actually begin the epic. To translate one form into another, from poetry into a form even so richly eloquent as opera, is filled with difficulties. Milton is concerned with light in its various manifestations—personal, moral, ethical, spiritual; and he is eager to demonstrate through the power of poetry the illumination of reality. As the light comes up on the stage, and the voice of Milton sounds over these initial chords, something of Milton's ambitious desires are conveyed to us in a new and not inferior way. Not heard in these excerpts is the briefly dramatized scene of Adam and Eve's recrimination of each other after the fall, and also their despair—an anticipation of all that will follow in the course of the opera. Here the creation occurs before we meet Satan in Hell, and Satan, Sin, and Death at Hell's Gate. But much of the action in Milton's poem is temporally confused, with events that overlap and often occur at the same time. Thus the rearrangement of episodes in Fry-Penderecki seems justified, certainly in terms of their wish to make an obviously coherent drama that moves from beginning to end in a largely sequential way.

13. What one misses in the opera—something that the librettist and composer seem unable to depict—is the complexity of Satan's character from his boastfulness in books 1 and 2 to his dreadful determination in book 4, to the several stages of his temptation of Eve in book 9. Satan is much more prominent in the opera than he is in Milton's epic, for in Penderecki's composition he nearly becomes the protagonist because of the absence of a thoroughly realized God and Son. In Milton—and not so clearly or convincingly in Penderecki—the conflict between Heaven and Hell, between good and evil is enacted in the struggle of Adam and Eve. As archetypes of all mankind, the ultimate battle takes place in them, yet it is mediated and soothed through the Providential grace of God and of his Redeeming Son.

14. Emotional states are generally not well conceived or represented in the opera. Nevertheless, one must admire the extraordinary musical description of Eve's dream, and then of her intoxicated delight after she disobediently eats of the forbidden fruit—these two scenes are musically similar, though Milton treats them much more ambivalently. Penderecki was wise to describe his opera as a Sacra Rappresentazione, a kind of oratorio or a work with fixed scenes and little character development. Is it possible to portray in another form—here in operatic terms—the interaction and development of character so fully displayed in Milton's epic? Although Penderecki's Paradise Lost possesses much human drama and conflict, I think his opera eludes the kind of compelling staging and personal development that one can see, let us say, in Otello, or Don Carlo, or Lady Macbeth of Mtensk, or indeed of Wozzeck—but these all are adaptations of dramatic, not epic, not cosmic works. Yet Penderecki has certainly achieved much. Although a universal drama like Paradise Lost cannot perhaps ever be fully realized, even on the operatic stage, Penderecki has provided the best that has so far been attempted.

Responses to this piece intended for the Readers' Forum may be sent to the Editor at M.Steggle@shu.ac.uk.

![]()

© 2011-, Annaliese Connolly and Matthew Steggle (Editors, EMLS).