"The representing of so strange a power in love": Philip Sidney's Legacy of Anti-factionalism

Richard Wood

Sheffield Hallam University

Richard.wood@student.shu.ac.uk

Richard Wood." 'The representing of so strange a power in love': Philip Sidney's Legacy of Anti-factionalism". Early Modern Literary Studies Special Issue 16 (October, 2007) 4.1-20<URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/si-16/woodsidn.htm>.

- Although Philip Sidney's Arcadia was completed in the

previous decade, it was in fact a work of great literary significance to the

1590s. In particular, the literary quarrel associated with the different

publications of the romance reflected the conflicting political philosophies of

the publications' editors. This was a dispute over Sidney's literary heritage,

with added importance for the possible future direction of a state dogged by

factionalism. One of Sidney's early editors, Fulke Greville, chose to connect

the Arcadia with one particularly prominent faction of the 1590s: the

Essex circle. In doing so, as Joel Davis observes, Greville associated the

romance with the divisiveness "that eventually wore down men like himself

and Robert Sidney [Philip's brother] — and which would help destroy [Robert

Devereux, second Earl of] Essex".[1]

The other party to this literary argument, Mary Sidney Herbert (Philip's sister),

had a different conception of the political importance of the Arcadia,

based on an anti-factionalist agenda. I contend that this latter philosophy is

the more significant of the two for reading the New Arcadia (Sidney's

incomplete revision) in particular, and that the key to understanding the conciliatory

nature of the revised romance lies with its female characters; they are crucial

elements in Sidney's legacy to later decades.

- According to Jean Robertson, the editor of a

modern Oxford edition of The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia, Philip

Sidney's prose romance was originally begun "soon after his return from

his embassy to Germany in June 1577", and the first draft was completed by

1581.[2]

This original work has come to be known as the Old Arcadia. Victor

Skretkowicz, another editor of a modern Oxford edition, argues that Sidney's

radical reworking of his romance "might have begun...as early as 1582 and

continued into 1584".[3]

This revised version, which remained incomplete at Sidney's death in 1586, is now

known as the New Arcadia. Sidney's closest friend, Fulke Greville, was

one of the editors who supervised the publication of the revised work in 1590.

Three years after the publication of what has come to be seen as Greville's

edition, Philip Sidney's sister, Mary Sidney Herbert, the "Countess of

Pembroke" to whom the romance was dedicated, supervised the publication of

another Arcadia, combining the revised work with the third, fourth and

fifth books of the Old Arcadia; this is often referred to as "the

composite Arcadia". The Old Arcadia, used by Sidney Herbert

for part of her 1593 edition, was originally circulated in manuscript and

thought to be lost until the first manuscript example was discovered by Bertram

Dobell in 1907.

- The marked differences between Greville's 1590

edition and the Countess of Pembroke's later edition have been the subject of

much scholarly debate, often centring on the contrasting literary agendas they

reveal. In his article, "Multiple Arcadias and the Literary Quarrel

between Fulke Greville and the Countess of Pembroke", Joel Davis examines

the writings of both Greville and the Countess that were produced around the

time they were involved in editing their respective Arcadias. Davis

concludes that Greville's editorial practices serve "to highlight

philosophical similarities between himself and Sidney", thus casting

Sidney as "a courtier-soldier who had rejected the effeminate lures of

pastoralism to embrace a stern Stoic moral and political philosophy".[4]

In doing so, Davis argues, Greville wished

to represent Sidney and the Arcadia as intellectual precursors to the Tacitean political thought beginning to emerge at the same time in the circle of Robert Devereux, the earl of Essex, who had become Greville's patron.[5]

The "Tacitean political thought" that became associated with the Essex circle in the 1590s was of a more pessimistic strain than that often associated with the reading of Tacitus before the disappointments, as Greville would have seen them, of the 1580s. Greville and other like-minded forward Protestants, including Sidney, while he was still alive, were most disappointed with Elizabeth's failure to sanction active military opposition to the forces of Catholicism on the Continent, particularly in the Low Countries. Paradoxically, the Earl of Leicester's belated and brief attempt to prosecute this very action on Elizabeth's behalf symbolised the collapse of Greville's hopes; it was during Leicester's campaign that Sidney met his death in battle, at Zutphen in 1586.

- The use of the writings of the Roman historian,

Tacitus, in Renaissance political theory originates with Leonardo Bruni, the

Florentine humanist (c.1370 – 1444). Bruni believed, based on his

interpretation of Tacitus, "that a people is bound to achieve greatness as

long as there is freedom to take part in the business of government, and bound

to fall into corruption as soon as this liberty is taken away from them".[6]

Such ideas were still current during the latter part of the sixteenth century and

they would have chimed very clearly with those members of Elizabeth's court who

felt they were excluded from participation in the serious matters of state. In

the early 1580s, while it still appeared that the likes of Sidney might achieve

some influence over the course of political events, Tacitus was read as part of

a broader, optimistic Neostoicism, which encouraged such courtiers to view

themselves as more powerful than the realities of Elizabethan absolutism would

seem to have allowed. This outlook is most tellingly evoked in the work of

Justus Lipsius, a prominent Flemish Neostoic who was heavily influenced by

contemporary Taciteanism, and who was a correspondent of Philip Sidney.

Lipsius, elucidating the meaning of the Stoic motto, nec spe nec metu ("neither

in hope nor in fear"), wrote, "Thou shalt be a king free indeed, only

subject unto God, enfranchised from the servile yoke of Fortune and affections".[7]

- Such optimism was not to last. Whether he had

intended it or not, by associating Sidney's Arcadia with Tacitean

thought, Greville had in fact yoked Sidney's romance to an increasingly bleak

philosophy: a philosophy espoused by Elizabethans who sought "examples of

tyranny and corruption that might validate their own experience" rather

than "examples of virtue amid adversity".[8]

Joel Davis's thorough analysis of the chapter summaries added to the 1590 Arcadia

suggests that Sidney's friend was indeed at pains to highlight "the darker

and more politically cynical aspects" of the romance, stressing "whenever

possible Sidney's treatments of constancy in the face of political oppression"

and trying "to make his audience read Sidney as the English Taciteans

[were now reading] Roman imperial history".[9]

- Mary Sidney Herbert, in the construction of the

1593 edition of the Arcadia, removes the editorial scaffolding with

which Greville's "Tacitean" edition had apparently been erected: the

chapter divisions and summaries are excised; the work's pastoral nature is

underscored; and, as Joel Davis puts it, "under the rubric of pastoralism,

[Sidney Herbert seeks] to extend a blanket of familial sympathy around the Arcadia

that excludes Greville and his interpretation of the work".[10]

As Joel Davis has argued, Mary Sidney Herbert's

conception of the Sidney family discourse, however consciously she herself

thought of it in those terms, was at odds with that of Greville and the Essex

circle.[11]

Most significantly, Sidney Herbert espoused an alternative version of

Neostoicism from that attributed to Greville. As is evident from Mary Sidney

Herbert's translation of Philippe Du Plessis-Mornay's Discours de la mort et

de la vie, published in 1592, the Countess shared Mornay's belief that

corruption stems from the kind of political factionalism that was prevalent in

Elizabeth's court. Rather than associating corruption with the lack of freedom

available under a tyrannical regime, as Greville does, Mornay and Sidney

Herbert place the responsibility with the court and, by implication, the

courtiers themselves.

- There is also much evidence to support the idea

that Philip Sidney shared his sister's beliefs, not least from his own

unfinished translation of Mornay's De la vérité de la religion Chrestienne,

which was apparently completed by Arthur Golding, the renowned translator of

Ovid's Metamorphoses, and published in 1587.[12]

As Martin Raitière observes, Mornay's De la vérité de la religion

Chrestienne "may be viewed as an attempt to give a philosophical

underpinning to the Politique idea" that, in France, "to holy war

should be preferred the mundane compromise of peace".[13]

In his sophisticated argument against Mornay's authorship of the monarchomach

treatise, Vindiciae contra tyrannos (1579), Raitière characterizes

Mornay's publications as consistently irenic, from the Remonstrances in

favour of peace of 1576 (also the year of the Discours), through the Vérité

(1581) and beyond.[14]

Citing the chapter from the Vérité in which Mornay makes the case that

there is only one God, Raitière notes that Mornay "develops the theme of

unity in a political sense".[15]

Both translations, Philip's of the Vérité and Mary's of the Discours,

make Mornay's anti-factionalist doctrine more widely available. Although the

two texts may differ quite significantly in several other respects, it is their

consistent irenicism which is significant here.

- The sequential publication of a second edition of

the translation of the Vérité in 1592, Mary Sidney Herbert's "composite

Arcadia" in 1593, and the Countess's collection of Sidney's works

in the edition of the Arcadia published in 1598 (each arguably

consistent in their philosophy) successfully, as Davis concludes, "reclaimed

from Greville the literary figure of Sir Philip Sidney for the Sidney family".[16]

It is particularly

ironic that this early division about the correct way of reading Sidney's work

should rest on the damaging effects of divisiveness. Knowledge of the anti-factionalism at the heart of

Mary Sidney Herbert's conception of the Sidney family discourse is significant,

I contend, for reading the New Arcadia. Moreover, the association,

highlighted above, between Mary Sidney Herbert's philosophy and the "effeminate lures of pastoralism"

readily suggests the importance of gender for such a reading. As such, I argue

that Sidney's female characters hold the key to understanding the

anti-factionalist agenda of the New Arcadia.

- The plot of the Arcadia, in its original

form, centres on the Duke Basilius, who seeks advice from the oracle at

Delphos, and, acting on its prophecies, leads his dukedom into chaos. One of

his ill-advised measures, based on his mistaken belief that he can avoid the

events predicted by the oracle, is intended to protect his two daughters, the

princesses Philoclea and Pamela, from the sinister attentions of any passing

princes. Unsurprisingly, Basilius fails and they become the objects of desire

for Musidorus and Pyrocles, two princes who are also cousins. The story concludes

with a trial of the princes for Basilius's death and the rape of his

daughters. They are eventually judged and condemned to death by Pyrocles's

father (Musidorus's uncle), Euarchus, only for Basilius to return, apparently

from the dead, forgive everyone their wrongdoings and sanction the princes'

marriage to his daughters. The New Arcadia, by contrast, has been described by Richard McCoy

as "culminat[ing] in a pattern of ambivalence and evasion".[17]

Indeed, apparently echoing this assessment, it has elicited a less than securely founded criticism.

Katherine Duncan-Jones, in an insightful reading of the revised text,

summarises the characteristics that have induced such hesitancy among other

critics:

As the narrative unfolds, it is full of surprises. Books 1 and 2 have a labyrinthine structure of episodes, flashbacks and subsidiary narratives, yet incorporate most of the narrative of the equivalent books of the "Old" version. Book 3 leaves it far behind, both emotionally and geographically, replacing sexual intrigue with dark images of imprisonment and pointless conflict.[18]

It is with those "dark images of imprisonment and pointless conflict" that I particularly wish to engage: I shall illuminate my argument by reference to a much debated portion of the New Arcadia: the "captivity episode" from Book III.[19]

- In this section of the New

Arcadia, Pamela, Philoclea and Zelmane (the name assumed by the

cross-dressing Pyrocles) are captured by the agents of Cecropia, Basilius's

ambitious sister-in-law. She wishes to force one of the princesses to marry

her son, Amphialus, and win control of her brother-in-law's dukedom. When the

captives come face-to-face with Cecropia herself, Philoclea, sharing in "the

deadly terror" that this meeting produces in the sisters, beseeches her

aunt-in-law "to be good unto them, having never deserved evil of her".[20] Pamela, however, signals

her intention to endure whatever torments lay in store with stoical fortitude: "'Aunt,'

said she, 'what you have determined of us, I pray you, do it speedily. For my

part, I look for no service where I find violence'" (317/13-14). Of the

two sisters, Pamela judges Cecropia correctly, and it is Pamela's stoical

resistance to the torments which follow that has coloured much of the critical

response to the New Arcadia. This is unsurprising. The staged contest

between Pamela's proto-Christian Stoicism and the atheist Epicureanism of

Cecropia would have provided a ready model of stoical Christian virtue for

Sidney's contemporary audience and his readership in the decades which

followed. Indeed, the author of Eikon Basilike (1648) suggested that

Pamela's prayer from this episode of Book III was used by Charles I during his

imprisonment at Carisbrooke Castle, prior to his execution in 1649.[21] Nevertheless, I wish to

draw attention to the other princess who is subjected to Cecropia's malicious

attentions, Philoclea. Although she is rather dismissively described by

Katherine Duncan-Jones as "giv[ing] herself up to weeping and self-neglect",

I suggest Philoclea's captivity narrative provides an illustrative example of

the complex relationships that arise between members of the apparently diverse

factions in Sidney's revised romance.[22]

- Amphialus, having already

declared his desire for Philoclea, but also under the malign influence of his

mother, Cecropia, approaches Philoclea's chamber intending to seduce her. He

finds her with her head partially covered, facing the wall, but does not

disturb her:

her hands and fingers as it were indented one within the other, her shoulder leaning to her bed's head, and over her head a scarf which did eclipse almost half her eyes, which under it fixed their beams upon the wall by, with so steady a manner, as if in that place they might well change, but not mend, their object—and so remained they a good while after his coming in, he not daring to trouble her, nor she perceiving him; till that, a little varying her thoughts something quickening her senses, she heard him as he happed to stir his upper garment (321/30-322/2).

And so their meeting begins in silent passivity. Moreover, when they do speak, Amphialus seeks to distance himself from active participation in the maintenance of the princess's captivity, preferring to resort to the trope of personified "love" as the agent of her imprisonment:that tyrant, love, which now possesseth the hold of all my life and reason ... It is love! It is love, not I, which disobey you ... I am not the stay of your freedom, but love—love, which ties you in your own knots (323/28-33).

Here Philoclea, literally Cecropia's captive, is also apparently the passive victim of her own allure, this latter, metaphorical, captivity being the work of "that tyrant love". Indeed, Amphialus is also, as he later claims, so restrained by "love" that he is unable to fulfil his mother's wishes, and so Philoclea's virtue remains intact. Philoclea's influence over Amphialus does not merely extend to maintaining her own safety: she is able to reconcile him to sparing his enemies from death. Amphialus, having captured Basilius's appointed regent, Philanax, calls for the prisoner to be brought before him with the intention "to cause him to be executed" (352/15-16). Amphialus "had not only long hated [Philanax], but now had his hate greatly increased by the death of his squire" (10-11). Nevertheless, Philoclea's influence stays Amphialus's hand:[Philoclea's] message was delivered even as Philanax was entering to the presence of Amphialus, coming, according to the warning was given him, to receive judgement of death. ...Amphialus turned quite the form of his pretended speech, and yielded him humble thanks that by his means he had come to that happiness as to receive a commandment of his lady; and therefore he willingly gave him liberty to return in safety whither he would, quitting him not only of all former grudge, but assuring him that he would be willing to do him any friendship and service (25-36).[23]

Philanax's answer to Amphialus's leniency indicates the familial bonds that cross the divide between the two Arcadian factions:let me now (having received my life by your grace), let me give you your life and honour by my counsel, protesting unto you that I cannot choose but love you, being my master's nephew... You know his nature is as apt to forgive as his power is able to conquer. [...] Do not urge the effects of angry victory, but rather seek to obtain that constantly by courtesy which you can never, assuredly, enjoy by violence (353/27-35).

Philanax's appeal to "courtesy" reflects what Blair Worden describes as the "emollient influence" of the themes of courtesy and chivalry, widely considered to be much more evident in the New Arcadia than the Old.[24] Worden challenges, if rather courteously, the view, posited by Richard C. McCoy and David Norbrook, that "Sidney's representation of chivalry contains the aggression and resentment characteristic of a martial nobility half-tamed by the Tudor court", and, as such, "the politeness of the New Arcadia cannot go very deep".[25] Indeed, the politeness may not "go very deep", but, I contend, the anti-factionalism does. This is apparent in Philanax's invocation of Amphialus's family ties, which, in turn, might be what prompts Basilius's nephew to think on his cousin, Philoclea, again in response:One might easily have seen in the cheer of Amphialus that disdainful choler would fain have made the answer for him, but the remembrance of Philoclea served for forcible barriers between anger and angry effects (353/36-354/1).

However, it is important to note that Amphialus's conciliatory behaviour is not produced by his recognition of a common ancestry with his enemies. The common theme is that of Philoclea's sway, in whatever manner it is brought to bear.

- The nature of Philoclea's influence over

Amphialus is important to understanding the efficacy of the irenical philosophy

of the New Arcadia that she represents. As I indicated above,

Amphialus, when speaking to Philoclea, characterises her imprisonment as the

work of "that tyrant love". In a later dispute with his mother,

Amphialus depicts "true love", of which he professes to be the

embodiment, as "a servant" and "lust" as the "tyrant":

Mother, O mother! Lust may well be a tyrant, but true love, where it is indeed, it is a servant...if ever I did approach her, but that I freezed as much in fearful reverence as I burned in a vehement desire. Did ever man's eye look thorough love upon the majesty of virtue shining through beauty, but that he became—as it well became him—a captive? (401/34-402/1)

In both instances Amphialus attributes his behaviour to the agency of "love", a force inspired by, if not originating with, Philoclea. In the former case, when speaking to the princess, it is possible, for the sake of expediency, that Amphialus might wish to emphasise the influence that true love, rather than lust, has over his actions, and, similarly, in his conversations with Cecropia, that he is more concerned to deny, rather than admit, any suggestion of his own ineptitude. However, throughout the episode as a whole, it is clear that Amphialus's encounters with Philoclea, and her "majesty of virtue shining through beauty" effects more than a mere change in his rhetoric. Indeed, as we have already seen, Amphialus's "captivity", as he portrays it, has prevented him from assailing the princess's virtue, and his memory of her has functioned as "forcible barriers between anger and angry effects", to Philanax's benefit. Nevertheless, despite Philoclea's presence, as Katherine Duncan-Jones might put it, "the imprisonment and pointless conflict" continues. Certainly, the conflict, at least as far as the incomplete revised version of the romance is concerned, has no end: the text finishes mid-sentence, and Sidney's resolution, if indeed he intended one, remains unknown. This presents obvious problems of interpretation, particularly when determining the guiding philosophy of the New Arcadia. It does, however, have the advantage of reflecting the Elizabethan political scene as Sidney himself left it: riven by factions. This is the same political context that informed the divergent philosophies of Mary Sidney Herbert and Fulke Greville. In the worlds of the New Arcadia and Elizabethan politics, Philoclea's (or Mary Sidney Herbert's) irenical Stoicism had yet to prove a success or a failure. Yet, despite the lack of any such conclusive fictional, or historical, approval, I suggest the signs of its effectiveness are discernable in Sidney's text, even, rather paradoxically, in martial combat.

- Throughout Book III, as a counterpoint to

Amphialus's restraint, Cecropia emphasises her disdain for any form of

passivity; she tells her son, "I, remembering that in all miseries

weeping becomes fools, and practice wise folks, have tried divers means to pull

us out of the mire of subjection" (319/21-23). This contrast in their

outlooks is further emphasised when, in the midst of her son's paralysis, Cecropia personifies

love as a military general:

If you command your soldier to march foremost, and he for courtesy put others before him, would you praise his modesty? Love is your general. He bids you dare. And will Amphialus be a dastard? (402/12-15)

Cecropia even resorts to classical exemplars of forceful action to further induce her son: "Do you think Theseus should ever have gotten Antiope with sighing and crossing his arms?" (402/15-17); "Iole had her own father killed by Hercules, and herself ravished—by force ravished" (21-22); "But above all, mark Helen, daughter to Jupiter, who could never brook her mannerly-wooing Menelaus, but disdained his humbleness and loathed his softness. But so well she could like the force of enforcing Paris that for him she could abide what might be abidden" (26-30). It is notable, particularly when determining where the balance of sympathy should fall between mother and son, that things end badly for the active parties in all of Cecropia's classical allusions.

- When Cecropia finally

concludes her entreaty, likening a woman to "a ready horse [that] straight

yields when he finds one that will have him yield" (403/6-7) and imploring

Amphialus to "show thyself a man" (13-14), her son is prevented from replying

by the arrival of a messenger carrying a challenge from the Forsaken Knight

(Musidorus in disguise). There is a parallel here with the occasion when

Philoclea's message to Amphialus prevented the execution of Philanax: in

both instances Amphialus is interrupted by messengers. He accepts the contest,

"shaking off with resolution his mother's importunate dissuasions"

(404/13-14), and rides to meet his challenger. This timely opportunity for

Amphialus to truly "show himself a man" appears to place the virtue

of knightly combat in favourable and stark contrast to Cecropia's "battle"

of the sexes; the juxtaposition also, seemingly, privileges honourable martial

action over Cecropia's "divers means". However, it is clear from

Amphialus's demeanour, as he rides to meet his foe, that he is still primarily

under the influence of Philoclea and her passive virtue:

Amphialus (already tender-minded by the afflictions of love)...without staff, or sword drawn...trotted fairly to the Forsaken Knight, willing to have put off his combat, to which his melancholy heart did, more than ever in like occasion, misgive him (405/10-14).

Hence, rather than leaving his "womanly" passivity behind (as Cecropia would have it), he, paradoxically, carries it into the contest.

- The gendered nature of

Amphialus's passive attitude is particularly emphasised by the use of the

phrase "without staff or sword drawn". As well as the obvious

connotation of male sexual impotence, there is a further, less immediate

association between the phrase "without staff" and the word

"distaff". A distaff is a staff on which wool or flax was wound in spinning.

As spinning was historically a form of labour usually performed by women, the

distaff came to symbolise "women's work", and, by extension, the

female sex: "the "spindle-side" as opposed to the

"spear-side"" of the family.[26]

If Amphialus is temporarily "without

staff" (dis-staff?), perhaps he is

"fitter...to hold a distaff"; this is how Thomas Moffett, in his

biography, Nobilis (presented to Sidney's nephew, William, Lord Herbert,

in 1594), characterises the "effeminate" men who, as Moffett believed,

envied Philip Sidney.[27]

- It is noteworthy that

Sidney himself, both in his An Apology for Poetry and Book I of the New

Arcadia, should also allude to the often depicted classical scene of "Hercules,

painted with his great beard and furious countenance, in women's attire,

spinning at Omphale's commandment".[28]

In the latter of the two cases, Palladius (Musidorus in disguise) meets

Pyrocles, who is in the guise of an Amazon, wearing a mantle held in place by

a very rich jewel, the device whereof...was this: a Hercules made in little form, but set with a distaff in his hand (as he once was by Omphale's commandment), with a word in Greek, but this to be interpreted: "Never more valiant" (69/5-9).

The image of Hercules spinning is invoked in An Apology to illustrate Sidney's case that laughter does not proceed from delight, but that they may coincide. Hercules's love for Omphale has persuaded him to undertake this action, and, for Sidney, "the representing of so strange a power in love procureth delight: and the scornfulness of the action stirreth laughter".[29] The potential for laughter notwithstanding, Pyrocles's actions are presented in a favourable light. He is apparently "Never more valiant", and although he is wearing a sword on his thigh, as is the custom of an Amazon, "it seemed but a needless weapon, since her other forces were without withstanding" (69/11-12). It might be said that he needs nothing other than Hercules's distaff. Indeed, the same could be said of Amphialus when he is "without staff": if not "commanded" by a woman, he is certainly strongly influenced by one. He is, like Hercules spinning, another representation of that "so strange a power in love" that has the ability to "procureth delight". In the New Arcadia, Palladius scorns Pyrocles that his "effeminate love of a woman [Philoclea in this case] doth so womanize a man that, if you yield to it, it will not only make you an Amazon, but a launder, a distaff-spinner" (72/6-8). In response, Pyrocles argues against any suggestion that his transformation implies a weakening, and even charges his own sex with going against its nature:I am not yet come to that degree of wisdom to think light of the sex of whom I have my life; since if I be anything..., I was to come to it born of a woman, and nursed of a woman. And certainly...it is strange to see the unmanlike cruelty of mankind, who not content with their tyrannous ambition to have brought the others" virtuous patience under them, like childish masters think their masterhood nothing without doing injury to them, who (if we will argue by reason) are framed of nature with the same parts of the mind for the exercise of virtue as we are (72/26-73/2).

Although, as Mary Ellen Lamb observes, Pyrocles's arguments are undermined by his admissions (in his song and elsewhere) that his "poor reason's overthrow" (69/26) and his "heart is too far possessed" (75/17), the case for the "power in love", both here and in Book III, remains strong.[30]

- Philoclea's influence

over Pyrocles is clearly problematic, not least in terms of gender equality, if

the latter's adoption of the feminine requires the deposition of reason in

favour of the unruly heart. When, in Book III, Amphialus rides to meet the

Forsaken Knight's challenge, Philoclea's irenicism would seem similarly to

have reached its limits. Musidorus (as the Forsaken Knight) is acting

primarily in defence of Pamela, but Amphialus mistakenly perceives that he is "his

rival" (405/34) in love for Philoclea - "each indeed mistaking other"

(33-34). On this occasion remembrance of the princess does not prevent Amphialus

engaging with his opponent in active combat, rather, he declares that "it

proceeds from their [the princesses"] own beauty to enforce love to offer

this force" (22-23). Nevertheless, there is a final parallel that serves

to confirm the importance of Philoclea's Stoicism in what might otherwise seem

like "pointless conflict": the Forsaken Knight's armour bears an

impresa (or emblem) in the form of "a catoblepta" (405/1-2). A

catoblepta (often referred to with various spellings, including catoblepas and

catablepon) is an animal, apparently from Egypt, that Sidney could have first

read about in Mornay's De

la vérité de la religion Chrestienne or Pliny the Elder's Naturalis

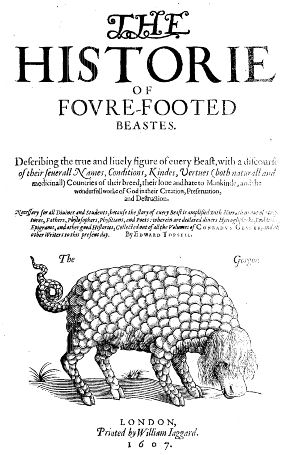

historia. As can be seen from the image on the title page of Edward

Topsell's The

historie of foure-footed beastes (published in 1607), the catoblepta has its head lowered and

a considerable fringe covering its eyes.[31]

This countenance is associated with the belief that such a creature's eyes, if

seen, would kill the viewer:

From the crowne of their head downe to their nose they haue a long hanging mane, which maketh them to look fearefully...These Gorgons [as Topsell categorises them] ...haue such haire about their heads as not onely exceedeth all other beastes, but also poysoneth when he standeth vpright. Pliny calleth this beast Catablepon, because it continually looketh downeward, and saith that all the parts of it are but smal excepting the head which is very heauy, and exceedeth the proportion of his body which is neuer lifted vp, but all liuing creatures die that see his eies.[32]

Figure 1. Catoblepta from the title page of Edward Topsell's The Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes (1607)

- Although the comparison is less than flattering, there is a

parallel between the appearance of the catoblepta and that of the imprisoned

Philoclea: "over her head a scarf which did eclipse almost half her eyes,

which under it fixed their beams upon the wall by, with so steady a manner, as

if in that place they might well change, but not mend, their object"

(321/32-35). Moreover, Philoclea has a similar ability to transform, if not to

kill, someone who gazes upon her. As Amphialus puts it, "Did ever man's

eye look thorough love upon the majesty of virtue shining through beauty, but

that he became—as it well became him—a captive?" (401/38-402/1)

- There is a degree of ambiguity in the language of

seeing and being seen in the New Arcadia which appears to make the

correspondence between Philoclea's capacity and that of the catoblepta rather

imprecise. The princess's eyes "fixed their beams upon the wall...as if

in that place they might well change, but not mend, their object",

whereas, elsewhere the emphasis is on being seen. Indeed, the catoblepta would

seem to require its eyes to be seen to have its fatal effect. This conundrum

may be solved by adopting the concept of "eye-beams" as a means of

explaining the faculty of sight, prevalent in the Early Modern period. Indeed,

this early scientific hypothesis, whereby the eye emits a "seeing"

beam rather than receives light, would seem to be at play in the English

translation, partly attributed to Sidney, of Mornay's De la vérité de la

religion Chrestienne, where it discusses the catoblepta. The curious

Egyptian creature serves as an analogy for understanding the minds of men

"bent and intended to nothing but mischief":

Or what els is such a mynd, than ye eye of the beast of AEgipt, which killeth those whom it looketh vpon, and it self also by ye rebounding back of his owne sight? Some in deede doo lift vp ye eye of their mynd aloft; but how farre or what see they?[33]

Here seeing the eyes and being seen by them are equally hazardous. Moreover, the suggestion that Philoclea's averted gaze, her "scarf which did eclipse almost half her eyes", and the creature's "long hanging mane, which maketh [it] to look fearefully", are means of self-preservation echoes the double-edged nature of the princess allowing Amphialus to see her: her shining virtue (her defence) becomes visible and henceforth active, but she also arouses her captor's desire.

- For her virtue to have an active influence in her

world Philoclea must be seen, but this exposes her to tyranny. In this respect

Philoclea and Amphialus complement each other. Rather pointedly, this reflects

the relationship between the two emblems emblazoned on the armour of both the

Forsaken Knight and Amphialus as they enter combat. As we have seen, the

former's impresa is a catoblepta. Amphialus "bare[s] for his device a

night" (404/23-24); it must be assumed from what follows that the

"night" depicted on Amphialus's shield contains a moon. Indeed, the

peculiar significance of these symbols only becomes known when it is revealed

that the catoblepta "lies dead as the moon, where it hath so natural a

sympathy, wants her light", and written beside it, "[t]he word

signified that the moon wanted not the light, but the poor beast wanted the

moon's light" (405/2-5). In other words, the creature needs the light of

its enemy, that of the moon on Amphialus's armour, to live, to fight.[34]

These foes are in fact true counterparts.

- It is through the complex employment of such parallel images that, I contend, even the most labyrinthine and apparently pointless passages of the New Arcadia reveal its philosophy. Unlike his avowedly wicked mother, Amphialus is shown to be open to the influence of the princesses" stoical virtue. Hence, that virtue, perhaps like Sidney's literary project itself, has the potential to reconcile apparently irreconcilable factions. Here Stoicism can be seen as an "emollient influence", a status previously reserved for "courtesy and chivalry" in the world of Sidney's New Arcadia.[35] It is this very "nexus of ethics, politics, and rhetoric" that provided the philosophical basis for the New Arcadia's solution to the factionalism that, Sidney believed, was weakening England.[36] Through its consecutive publications, Sidney's romance was able to represent "so strange a power in love" throughout the 1590s and beyond.