How Should One Read a Shakespeare Sonnet?

Bruce R. Smith

University of Southern California

brucesmi@college.usc.edu

Bruce R. Smith. “How Should One Read a Shakespeare Sonnet?” Early Modern Literary Studies Special Issue 19 (2009) 2.1-39 <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/si-19/smitsonn.htm>.

-

How should one read a Shakespeare sonnet? Carefully, you might be thinking. Or skeptically, if your stance is deconstructive. Or reverentially if it’s not. Or referentially if you want to consider the social work the poem was doing in its own time. Or super-subtly if you want to know who “he” and “she” really were. I have in mind something more tech. Let us begin with a single sonnet, communicated in two different ways. Here is the first version:

Movie 1: A sonnet in ASLWhat you see here is one of Shakespeare’s best known sonnets interpreted into American Sign Language (ASL) by Crescenciano (Chris) Garcia of Los Angeles, California, recorded in September 2006. Any sense of just which sonnet is being communicated? Could you read it? How did you manage to do that? Different technical means of communication ask for different modes of reading. What did you look to for cues?

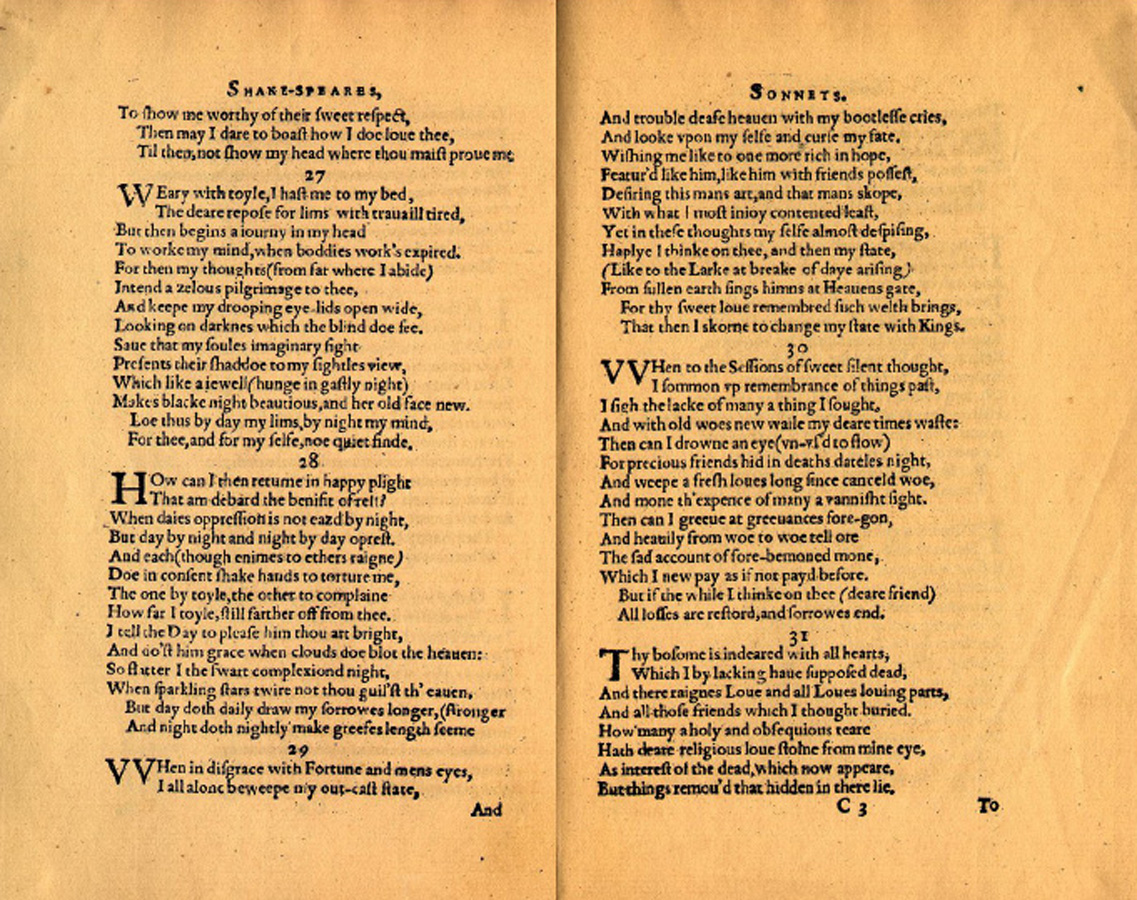

- Here is

the same sonnet as it appears in the 1609 quarto of Shake-speares

Sonnets. Neuer before Imprinted. Once again, the mechanics of

communication are cuing a certain kind of reading. Because you are so

familiar with these mechanics, you may find it harder to isolate the

cues you are being given and read them as cues. Pay particular

attention to pronouns and prepositions:

Figure 1: Sonnet 29 in William Shakespeare, Shake-speares Sonnets. Never before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe, 1609.

-

Between

these two versions several large differences suggest themselves. The

first is a matter of ontology: version one is an embodied act,

whereas version two presents itself as a disembodied object. Sonnet

29 in ASL requires the physical presence of a signer: the signs do

not exist apart from the signer’s body. Signatures C2v and C3 in Shake-speares Sonnets may have required fingers, hands, arms,

and a brain or two to make them, but the finished product exists

quite apart from those bodies. The signs are impressed into the paper

with lead and ink, and they remain right there, whether or not there

is anyone around to see them, whether the book is open or closed. A

second difference is epistemological. How do the signs get read? How

is meaning constructed by the reader? In version one what gets read

is the signer’s body; in version two, it is marks on the page.

Needless to say, the decoding process in each case is different.

Media of reception constitute a third difference. Sonnet 29 in ASL

seems to be communicated entirely through sight, whereas some amount

of subliminal sounding goes on even in the fastest visual scanning of

written texts. Poetry positively demands such sounding. Chronology

shapes up as a fourth difference: Chris Garcia’s signing brings

Thorpe’s 1609 text (very much there and then, especially as the

text appears in the above figure) into the here and now. In

linguistic terms, finally, we are confronted with two different

organizations of signs: a language of gesture in version one versus a

language of words in version two.

- These

patent differences in the construction of meaning cry out for de-construction. For a start, reading a codex is an embodied

act. The book is an object positioned in space sixteen to eighteen

inches from my eye, something I hold in my hand, using my fingers and

thumb as an easel. My body is positioned vis-à-vis the book in

geometric space. The book remains an object “out there” even as I in-corporate “in here” the words printed on the page. On

second thought, reading the signer’s arms, hands, mouth, and eyes

may not be so different from reading marks on a page. To most

linguists, both ASL and early modern English shape up as two distinct

languages—no need for scare quotes with respect to the former. Each

comes equipped with its own vocabulary and syntax. Considered as

signs within a language system, arms, hands, mouth, and eyes do not

operate differently than marks on a page: they signify. Even

vision versus vision+sound turns out to be a false dichotomy. Chris

Garcia’s interpretation of sonnet 29 is not just visual: it

incorporates deliberate cheek and tongue “sounds” (scare quotes

appropriate for users who lack hearing entirely) that are part of

ASL. Look for them in the video. To someone literate in ASL those

clicks of the tongue and puffs of the cheek may not be heard with the

ears, but they are felt in the muscles of the mouth and face—a

circumstance that should make us consider that subliminal hearing of

a printed text is not just something that happens in the ears: it is

an experience of what it feels like to read, not just with

ears but with the whole body.

- Modern

psychology knows that experience as “proprioception,” defined by

the Oxford English Dictionary as “the perception of the

position and movements of the body” arising from muscle and nerve

tissues (OED, “proprioception,” n.). It amounts to

an internal sense of touch, which, as Helkiah Crooke points out in

his medical encyclopedia Microcosmographia (1615 and later

editions) “is not conteined within any proper organ or instrument

but equally diffused through the whole body” (531). Chronological

differences between here/now and there/then are likewise not so firm

as they first appear. Shake-speares Sonnets may exist as a

physical object—a codex measuring 18.75 cm (7-3/8 in) high x 13.34

cm (5-1/4 in) wide x 0.32 cm (1/8 in) thick and weighing about 56.7

grams (2 oz.)—but the sonnets contained within that object,

inscribed on its surfaces, happen only when a reader is

present, and reading happens only in the here-and-now.

- The most

suggestive deconstruction of all concerns gesture versus words.

Classical rhetoric has taught us to think of gesture as something added onto words. Quintilian in his Institutio Oratoria distinguishes five “canons” or “departments” of rhetoric, in

this precise order:

1 inventio (invention of matter or arguments)

2 dispositio (arrangement of those arguments)

3 elocutio (the style with which the arguments are to be presented)

4 memoria (memorization)

5 pronuntiatio (delivery) (3.3.1-3 in Quintilian 1921: 1: 382-84).Invention of arguments is a thoroughly verbal enterprise. Feeling and affect come into consideration with arrangement and style. Memorization locates the resulting decisions in the speaker’s body. But actions of the body—in particular, management of the speaker’s arms and hands—comes into play only as an after-thought. Thus Obadiah Walker’s textbook Some Instructions concerning the Art of Oratory (1659) advises, “Pronunciation ought to be accompanied with some decent action and comportment of your body. This action is especially of the eyes and the hands” (126, spelling modernized). Chris Garcia’s signing of sonnet 29 would seem to illustrate that chronology: first words, then gesture. (He is, after all, translating the sonnet from one language into another.) The case I wish to make here is, however, just the opposite. In all languages gesture comes first.

-

To grasp

that counter-intuitive proposition we need to distinguish two

fundamentally different models of language. The first is the one that

has held sway—in academic circles at least—since the so-called

“linguistic turn” of the late 1960s. In the transcribed lectures

that comprise Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General

Linguistics the professor distinguishes two ways of framing the

study of language. The more influential of these two frames in the

late twentieth century was langue: a critical interest in the

structures that make meaning-marking possible, a synchronic framing

of language in which particular utterances are less important than

the deep structure that makes all utterances possible. In our

fascination with these structural principles and the deconstruction

they enable, we have forgotten the other framing of language

described in Saussure’s linguistics: parole, the diachronic

consideration of language as it operates in time, language as

particular utterances, language as process, language as dramatic

event, language as speech-acts. Before langue, before parole,

Saussure recognizes a primordial chaos of thoughts and sounds. This

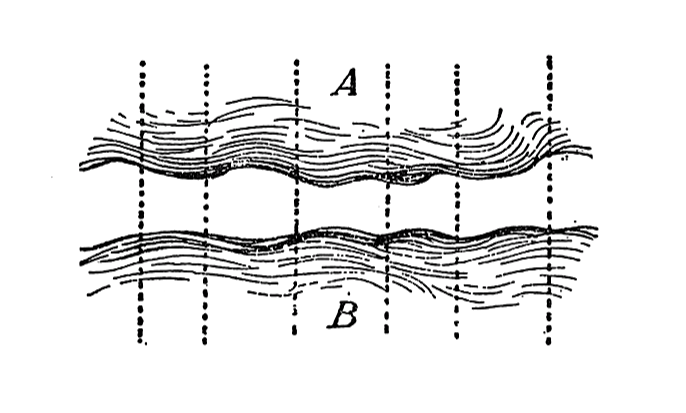

diagram (Figure 2)—much less familiar than the tree and the horse

that make every anthology of critical theory—comes from Part II,

Chapter 4, of the Course in General Linguistics:

Figure 2: Diagram from Saussure, Part II, Chapter 4, p156 (original French edition, 1916; also reprinted p111 in the 1959 English translation).

The letter A here designates what Saussure calls “the indefinite plane of jumbled ideas”; the letter B, “the equally vague plane of sounds” (122). Vertical lines indicate the cuts, the difference-markings that speakers make amid the chaos of thoughts and the plenitude of sounds. Saussure himself attended to the waves as well as to the lines, but most of his disciples since the linguistic turn have not done so. Their attention has been trained exclusively on the vertical lines, on the markings of difference. What has been lost to view is what might come before those marks.

-

A second

model of language is provided by Lev S. Vygotsky (1896-1934), whose

most famous book is Thought and Language, published in Russian

in 1934, eighteen years after Saussure’s students first published

in French his General Linguistics but just three years after

the corrected third edition that provides the text for the English

translations (1959, 1966, 1983) from which most participants in the

linguistic turn have taken their direction. “Thought” and

“speech”: the two entities in Vygotsky’s title are imagined,

just as in Saussure, to exist on two “planes,” one “external”

(the spoken word) and one “semantic” (the internally experienced

quality of thought). “These two planes do not correspond,”

Vygotsky insists. “There is a second, inner, plane of speech

standing beyond words. The independence of this grammar of thought,

of this syntax of verbal meanings, forces us to see—even in the

simplest of verbal expressions—a relationship between the

meaningful and the external aspects of speech that is not given once

and forever, a relationship that is not constant or static. What we

do see is movement. We see a continuous transition from the

[internal] syntax of meanings to the [external] grammar of words, a

transformation of sense structure as it is embodied in words”

(253). Where Saussure, Derrida, and most of their followers see a

“cut” or “bar,” Vygotsky sees movement. Vygotsky regards

speech, not as the content of “thought,” but as the completion of “thought.”

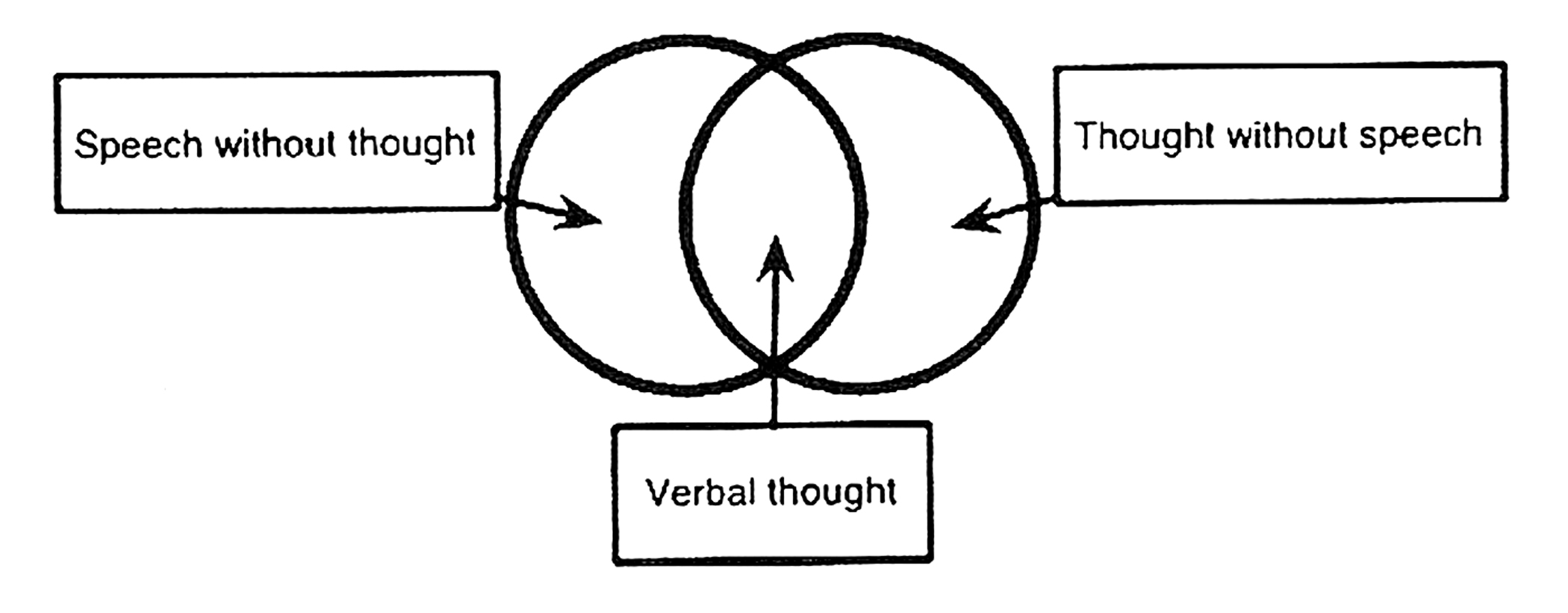

Figure 3: Venn diagram of Vygotsky’s “planes” (McNeill 81).

This image, devised by David McNeill for his book Gesture and Thought, realizes Vygotsky’s “planes” and the continuum between them as a Venn diagram that mediates between “Speech without thought” on the one hand and “Thought without speech” on the other. The overlap—relatively small in comparison with the other two areas—is what McNeill describes as “Verbal thought.”

- Wait. Can

there be thought without speech? Not according to Derrida in Of Grammatology (1967, English translation 1974). Not

according to Jerry Fodor in The Language of Thought (1975).

Not, indeed, according to most other philosophers of language since

the linguistic turn. Not according to cognitive scientists who assume

that the human brain is a particularly sophisticated computer,

processing information via a sequence of 1 | 0 switches that function

like Derrida’s marks of différance. An alternative

view is emerging from the experiments of Michael Spivey, who argues

in The Continuity of Mind (2007) that “the human mind/brain

typically construes the world via partially overlapping fuzzy gray

areas that are drawn out over time” (3). Perception of language as

well as perception of objects happens through constantly moving

trajectories within a “state space” inside the brain—a space in

which the two-dimensional planes and three-dimensional coordinates of

Euclidean geometry are extended into the infinite-dimensional space

needed to accommodate all the possibilities of mobile thought. When,

for example, you hear the sound frequencies that you recognize as

/k/, /a:/, /n/, and /d/, your neurons fire in a broad searching

pattern until /l/ confirms the word as candle or /i/ as candy and the “wrong” circuits shut down. Similarly with objects. Is

that two faces or a wine goblet that you’re seeing? Instead of a 1

| 0 data-processor Spivey posits a constantly moving, flowing mind that works in sync with a constantly moving, flowing array of

stimuli.

- As it

happens, Spivey’s quantum-mechanics model of perception works well

(certainly better than the computational model) with the hydraulic

model of perception that was entertained by Shakespeare and his

contemporaries. According to ideas derived from Aristotle’s

treatise “On the Soul” and Galen’s physiological writings,

external sensations are communicated to the brain, where they undergo

synaesthetic fusion in “the common sense” and are further shaped

by fancy, memory, and imagination before being sent via spiritus,

the body’s vaporous internal communication system, to the heart.

There desirable images cause the heart to dilate; repugnant images,

to contract. In both cases the entire body responds to the resulting

changes in body chemistry. Only in that altered state, when affect

has been added to perception, does judgment come into play in the

form of words, reason, and acts of will (Park 464-84). According to

Spivey’s experiments, the fuzziness that attends acts of perception

carries over into acts of verbalization: “self-conscious thoughts

are due to the language subsystem receiving its biased updates of the

meandering, looping, and loop-de-looping mental trajectory and

converting it (or collapsing its distributed wave function) into

individual words and phrases” (328). Spivey, trying to describe his

own internal monologues, notices “that the first few words of a

sentence often ring clear in my head like a well-trained newscaster’s

voice, and the next several are somewhat vague or poorly enunciated,

and the last few words of the sentence are left off entirely, because

I’ve completed the thought for myself by then and finishing the

linguistic version is unnecessary” (329-30). Not all

thought-without-speech ends in speech-without-thought. It is in the

in-between arena, what McNeill calls “verbal thought,” that

individual consciousness (thought-without-speech) intersects with

regimes of verbal language (speech-without-thought).

- As they

imply two different ways of making sense of the world, Saussure’s

and Vygotsky’s two models of language imply two different ways of

reading: one strategy that is attentive to words, to Derrida’s

“arche-writing,” to markings of difference, and one strategy that

is attentive to gesture, to the origins of communication inside the

human body, to the felt quality of thought before words. As a

way of gauging the differences between these two strategies of

reading, pronouns offer a particularly interesting test case. The

insistent first-personhood of Shakespeare’s entire collection of

sonnets is registered in sonnet 29. In this sonnet, as in all the

others, it is precisely the repetitions of “I,” “me,” “my,”

and “mine” that produce the irresistible “subjectivity effect”

that has been remarked by critics from Wordsworth to Joel Fineman.

- Sonnet 29

is altogether typical of Shakespeare’s sonnets in the triangulated

drama it plays out among “I,” “he,” and “thee.” The

twelve first-person pronouns in the poem’s fourteen lines are

contrasted in two ways, in two directions. In the octave “I” is

played off against four third-person Others: “one more rich in

hope,” “Featured like him,” “like him with friends

possessed,” “this man’s art,” “that man’s scope.” In

the sestet “I” turns from these assorted third-person Others to a

single second person—“Haply I think on thee”—and with that

shift in pronouns finds contentment that lasts even when the speaking

“I” glances at third-person Others in the couplet: “For thy

sweet love remembered such wealth brings/ That then I scorn to change

my state with kings”—with, that is to say, “them.”

- My own

head was turned by the linguistic turn, I have to admit, and this

interdependency among pronouns inspired an essay “I, You, He, She,

and We: On the Sexual Politics of Shakespeare’s Sonnets” that I

published in 1998, with a reprint in 2000. The pronouns in

Shakespeare’s sonnets may seem like fixed entities, I argued then,

but “I” needs the “not-I” in order to be “I”: “I”

needs “thou,” just as “I” needs “he” and “she,” and

“he” needs “she.” And none of these supposedly fixed entities

can stand alone: they are all implicated in each other. The

distinctions among them keep breaking down, so that the “we”

implicit in heterosexist (or, I would now add, homosexualist)

readings of the sonnets doesn’t hold up. All in all, I produced a

standard exercise in deconstruction, informed of course by Saussure’s

model of language.

- What

happens to the pronouns if we read sonnet 29 using Vygotsky’s model

instead of Saussure’s? They are still contingent, just as they are

in Saussure’s model, but they are contingent on

bodies-in-space-in-time. I asked Chris Garcia to show me how he

handled the pronouns in sonnet 29. In general, Chris explained, “I”

is located by a tap of a finger on the breastbone. As Chris explained

to me, the gesture toward the breastbone is much less important in

the signing of the first quatrain of sonnet 29 than the signs for

“tears” (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: “I alone”.

Figure 5: “beweep”.

In this scheme, “I” does not exist apart from “tears.” “I” and “tears” compose a single conceptual unit, in which the emphasis falls, not on “I,” but “tears.” What you see in the first frame (Figure 4) is the one moment in Chris’s interpretation when “I” assumes unusual importance, as Chris signs “I alone”: the tap to the breast is followed by a raised index finger for the number 1. Here is Chris’s literal, if you will, translation of what he is signing in the poem’s first two lines:

when happen / mess-up / embarrass / eyes stare

Where is “I” in this? Physically available for being gestured toward throughout the transaction, semiotically so in the sign for “alone,” but generally speaking “I” is inseparable from “embarrass,” “tears,” and “outcast”—all three of which hover in a syntactically indefinite space somewhere in between adjective (“outcast”), noun (“tears”), and verb (“embarrass”). “I” as a pronoun is, literally, nowhere to be seen, except in “I alone.” “Mess up,” “embarrass,” and “eyes stare” involve “you” as well as “I.” That is to say, they turn “I” into “you” and “you” into “I.”

leave alone / tears / my life / look like / outcast

- When it

comes to pronouns, Chris’s explanations of what he was doing made

me see how linear and hence how redundant the English language is.

The goal in signing, Chris told me, is to use as few signs as

possible with movements between signs that are as fluid as possible.

As a signer Chris first creates a precisely delimited

three-dimensional space with his hands and then proceeds to locate

within that space himself, the people about whom he is speaking, and

the people for whom he is signing. To indicate that a new idea

applies to a given person requires only a small gesture toward the

space that person occupies, actually in the case of listener/viewers

and symbolically in the case of absent persons who are being spoken

about.

- It is the

demonstrative pronouns in the second quatrain that best show the

process of thought that begins with preparatory gestures and proceeds

through various extensions of the speaker’s body into space, before

it ends with the definitive gesture that fixes the conception in the

eyes of the listener/spectators. Let’s follow Chris step by step:

The sequence begins with two fingers pointing to the chest, melded into the sign for “wish”: a downward movement on the chest with five bent fingers. “One more rich in hope” starts out as four bent fingers in each hand at disparate heights. The lower hand attempts to rise to the same level as the higher hand. The index finger of the lower hand then points to the higher hand as if to say, “This–what?” Four bent fingers in each hand move down the chest in parallel to answer that question: “This person.” A return to the video will show how important the ambient space is to the signer’s rendering of this particular quatrain. The raised index finger of the formerly lower hand points to the higher hand to indicate the first “like him” and repeats that gesture to indicate the second “like him” (Figure 6):Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

Desiring this man’s art, and that man’s scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least.

Figure 6: “One more rich in hope”.

“This man” and “that man” are more complicated still—and they implicate the listeners/viewers in the poem’s imaginative space. This frame (Figure 7) shows the signer beginning his search for “this man”:

Figure 7: Search for “this man”.

Here the gesture formally known as “two fingers outward” searches the listener/viewers. “This man” is found in this frame (Figure 8), when the index finger points to him:

Figure 8: “This man”, found

In this frame (Figure 9) the search begins for “that man”:

Figure 9

While the two fingers are still “looking” in the direction of “this man,” the speaker/signer has turned his attention in the opposite direction. Here (Figure 10) he is still looking:

Figure 10

Sweeping the listener/viewers with the two “looking” fingers, the speaker/signer finally turns his own gaze in the direction his hand has moved. Finally “that man” is found:

Figure 11: “That man” is found

A pointing index finger says that the speaker/listener has found “that man”—the one he has been looking for amongst the listeners/spectators.

The sequence of gestures, like the English verbiage of the poem, reaches its climax when the speaker/signer communicates “Haply I think on thee”:

Figure 12: “Haply I think on thee”

This Chris does by tapping an index finger on his temple, expanding outward in a circular motion with both hands, thus appealing directly to the listener/spectators, and at last gesturing toward them as “thee” in the sign you see in Figure 12: a “supine open five hand” moving in their direction. The fact that in this particular shot the hand seems to be replacing Chris Garcia’s mouth says it all.

- Where can

we locate Chris Garcia with respect to the two models of language?

Chris was, of course, working out of a verbal text, Shakespeare’s

sonnet 29 as it was printed in the 1609 quarto. Furthermore, he came

to the task with trilingual expertise in spoken English and spoken

Spanish as well as ASL. Chris began, then, in the left-hand circle of

David McNeill’s Venn diagram, in the arena of

speech-without-thought. (See Figure 3 above.) But by returning speech

to its pre-verbal origins within the body, Chris’s interpretation

reclaims the right-hand circle, thought-without-speech. If, in

Vygotsky’s scheme, words are an analogue of thought, Chris provides

gestures that are analogues of speech. In effect, Chris ends up

occupying a position in the overlap between the two arenas in

McNeill’s diagram. From that position Chris makes forays into the

other arenas. Most of those forays are into the arena of

thought-without-speech. Only in rare moments, as when he sets up the

simile in line 11, does Chris’s reading veer into the arena of

speech-without-thought.

- Metaphors,

which link things present with things not present, would seem

to present a challenge for remaining within the overlap between

thought and speech. As logical (or perhaps quasi-logical) operations,

metaphors require words. Take for example “Like to the lark at

break of day arising / From sullen earth / sings hymns at heaven’s

gate.” In the poem the indication of a metaphor and the bird come

first. The word “like” signals the metaphor up front and locates

the transaction within the arena of speech. In ASL, by contrast, the

transaction would begin in the arena of thought. The earth would be

contextualized first, then the bird would be put in it. It would be

more idiomatic in ASL, Chris explained, to render the lines this way:

Compare / round earth / quiet / sun rise / shine

In his interpretation Chris chose the harder course of emphasizing the contrivance of the concept and starting with the bird, which at first lacks the usual spatial context:

Bird awake / inspire / chirp / sing / offer up / towards heaven.

compare/ same bird / sit quiet / earth / sun rise / light beam

Chris’s solution puts the spatiality of earth in ASL in exactly the same syntactical position as it occurs in Shakespeare’s early modern English: fourth.

- Thanks to

the paucity of information about early modern acting techniques, John

Bulwer’s twin treatises Chirologia: or the Natural Language of

the Hand and Chironomia: or the Art of Manual Rhetoric,

although published 28 years after Shakespeare’s death, figure on

the horizon of most students of early modern drama. A sample plate

(usually the first of the publication’s six plates) appears in many

books about early modern theater, usually with a casual comment about

how modern viewers would find early modern acting technique stilted

and artificial, (e.g., witness the codified gestures that Bulwer

shows for expressing various passions). The composite plates look

like alphabets of a sort, alphabets made up of hand-signs rather than

letters:

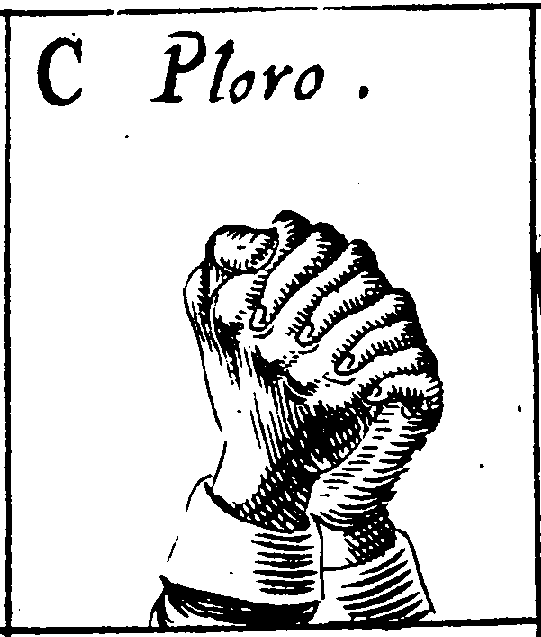

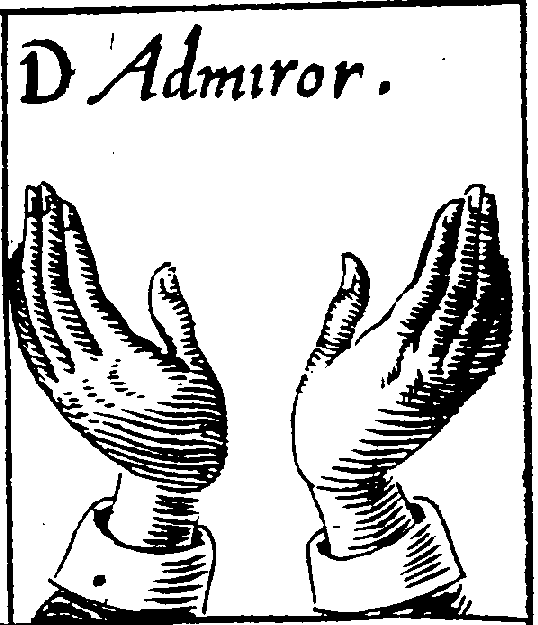

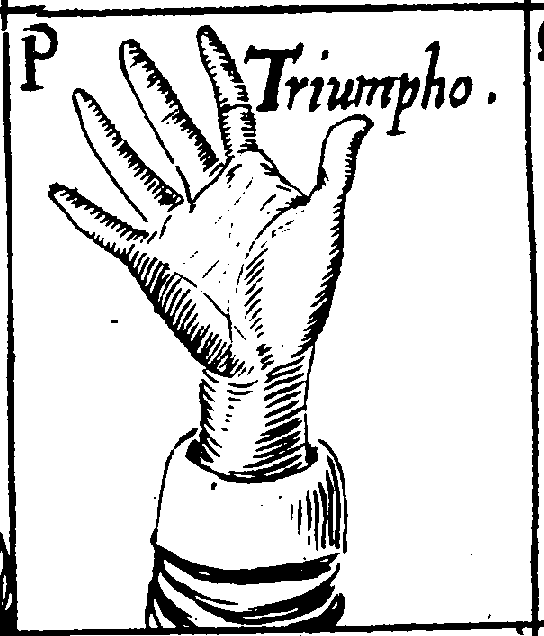

Figure 13: from Bulwer’s Chirologia

The Latin captions—see items C (Ploro), D (Admiror), and P (Triumpho)—suggest a visual dictionary or vocabulary list. Chirologia and Chironomia have both been regarded as a professional manual—literally a “handbook”—that seventeenth-century orators (and presumably stage actors) could use. That may be true of the second treatise, Chironomia, but what the first treatise, Chirologia, offers is in fact a complete, reasoned philosophy of language–and one that runs counter to Saussure and Derrida.

- In Chirologia Bulwer regards hand gestures not as ornaments that

occur after verbal signifiers, as most modern histories of

theater assume, but as meaning-formations that occur before verbal signifiers—and that often outpace them. Bulwer’s

deployment of the word “difference” gives an uncanny sense that

he has read Derrida’s Of Grammatology: “whatsoever is

perceptible unto sense, and capable of a due and fitting difference;

hath a natural competency to express the motives and affections of

the mind, in whose labors the hand which is a ready midwife takes

oftentimes the thoughts from the forestalled tongue, making a more

quick dispatch by gesture” (Bulwer 17). Bulwer instances the firing

of a piece of ordnance, in which the eye perceives the blast before

the ear hears the report. The reason for the primacy of gesture is

not just a function of light rays’ traveling faster through the air

than sound waves do: it has to with the embodiedness of thought. What

the hand is expressing is not just a certain “signified,” to use

modern terminology, but “signifying,” the trajectory of

thought that ends in that “signified.”

- Bulwer

emphasizes the power and temporal immediacy of fancy in the sequence

that leads from sensation to common sense to fancy to memory to

imagination to judgment. Fancy (or fantasy as we might term it today)

operates as a species of Vygotsky’s thought-without-speech: “For

when fancy hath once wrought upon the hand, our conceptions are

displayed and uttered in the very moment of a thought” (17,

emphasis added). What is more, hand gestures are closer than words to

“the true nature of things”: “all these motions and habits of

the hand are purely natural, not positive [i.e., “posited,” “put

out there”]; nor in their senses remote from the true nature of the

things that are implied. The natural resemblance and congruity of

which expressions result from the habits of the mind by the effort of

an impetuous affection wrought in the invaded hand which is made very

pliant for such impressions” (16). That is to say, hand gestures,

more than words, are imbued with what Antonio Damasio has called “the feeling of what happens.” In keeping with Bacon’s goals in The Advancement of Learning, Bulwer has no anxieties about

presenting his “natural” language of the hand as a universal

language. I do not share Bulwer’s aspirations in that regard, nor

do I wish to romanticize users of ASL (or any other sign-language for

that matter) as being in touch with a primitive essence that the rest

of us have lost. I do think, however, that ASL in conjunction with

Bulwer’s twin treatises can make us aware that language begins, not

in mental acts of marking, but in movements of the body.

- I am not

alone, I suspect, in having assumed that what Bulwer’s charts

illustrate are passions. Wrong. What those images demonstrate are, in

Hamlet’s words, “actions that a man might play” (1.2.84 in

Shakespeare 2005: 685). At end of his introduction to Chirologia, Bulwer sets up a phrase “For with our hands we…” and follows it

with more than two hundred verbs. All of the gestures

described and illustrated in Chirologia are expressed as

first-person verbs (“I…”) and represent only a small selection

of the more than two hundred that Bulwer has catalogued. The relevant

first-person verbs for Shakespeare’s sonnet 29 are ploro (“I

weep”), admiror (“I admire,” “I think on thee”), and triumpho (“I exult,” “I sing hymns at heaven’s gate”).

Let us consider these one by one.

Here is Ploro:

Figure 14

Bulwer’s gesture for “I weep” is derived from Francis Bacon’s Sylva Sylvarum, or A Natural History, the text that in fact inspired Bulwer’s entire project. According to Bacon, wringing of the hands as a sign of weeping has a physiological cause. “TO WRING THE HANDS,” Bulwer explains, “is a natural expression of excessive grief used by those who condole, bewail, and lament. Of which gesture that elegant expositor of nature [Francis Bacon in Sylva Sylvarum] hath assigned this reason: sorrow which diminisheth the body it affects provokes by wringing of the mind, tears, the sad expressions of the eyes, which [tears] are produced and caused by the contradiction of the spirits of the brain, which contradiction doth strain together the moisture of the brain, constraining thereby tears into the eyes; from which compression of the brain proceeds the HARD WRINGING OF THE HANDS which is a gesture of expression of moisture” (32, emphases original).

- Throwing

up the hands to heaven in the gesture Admiror (see Figure 15)

“is an expression of admiration, amazement, and astonishment, used also by those who flatter and wonderfully praise, and have others in high regard, or extol another’s speech or action” (33, emphases original).

Figure 15

Admiror, it is worth noting, is a so-called “deponent verb” in Latin: it exists only in passive-voice forms, even though what it signifies is generally understood to be in active voice. Literally translated, admiror ought to mean “I am admired.” Deponent verbs in Latin, Emile Benveniste has argued, are vestiges of middle-voice verbs in Greek and other Indo-European languages. Middle voice covers situations in which, as Benveniste puts it, “the subject is the center as well as the agent of the process; he achieves something which is being achieved in him … . He is indeed inside the process of which he is the agent” (149). Other examples that seem to occur in all Indo-European languages are the verbs for “to be born,” “to marry,” and “to converse.” Admiror in sonnet 29 involves not just the speaking “I” but the “thee” who inspires the speaking “I,” like a lark, to sing hymns at heaven’s gate. In deponent verbs the inscribed personal pronoun is implicated in third person or second person.

Triumpho, finally, is, as Bulwer puts it, “to put out the raised hand, and to shake it, as it were into a shout.” - The

gestures described in Chirologia are, Bulwer claims, “purely

natural, not positive.” Hence the appropriateness of first person

to designate the subject. One is “invaded” by the passion, one

“suffers” the passion. (Pati, from which the English word

“passion” derives, is another deponent verb.) The gestures

catalogued in Chironomia are, by contrast, contrivances: they

are “posited,” put forward as artistic devices. Rather than

accepting these gestures as the irreducible elements of

body-language, Bulwer takes a step backward in Chironomia and

attempts to isolate the “canons” of hand gestures by isolating

several dozen different combinations of finger and hand positions and

assigning them Roman numerals. The result is not “sufferings”

expressed in first-person verbs but performances expressed in third-person verbs. Chirologia catalogues gestures that

occur before words; Chironomia, gestures that occur after words. And those post-verbal gestures happen, not in

first person (“I do this or that”), but in third (“he does this or that”).

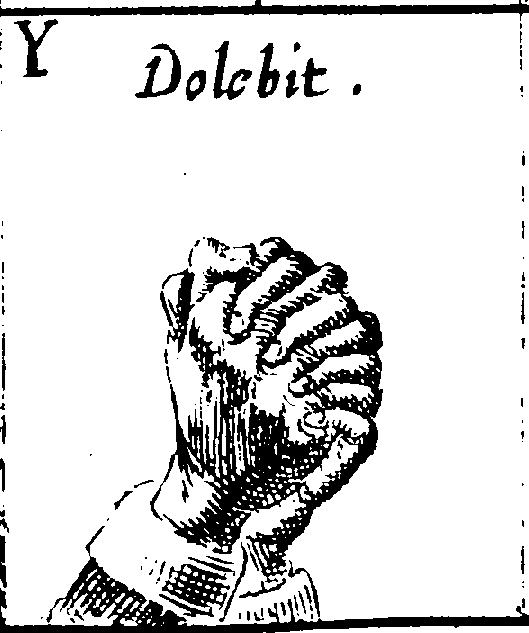

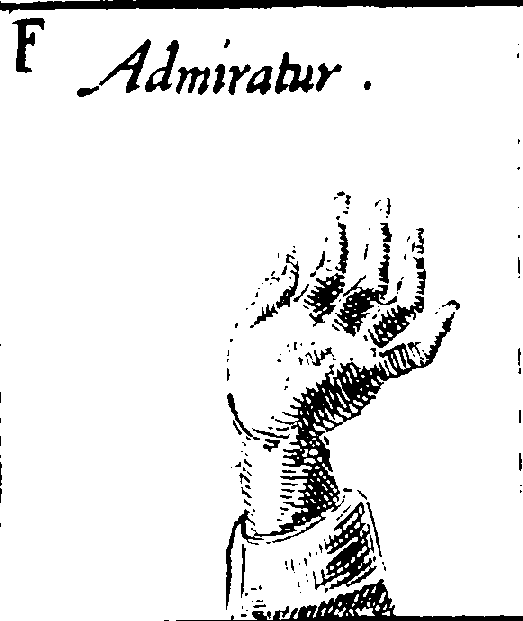

- Thus the

same gesture that “naturally” signifies Ploro, “I weep,”

in Chirologia becomes Dolebit, “he sorrows”—or

rather “he will sorrow”—in Chironomia:

Figure 17

(Why Bulwer or his engraver chose future tense for this particular gesture is not clear. Is an assumed passion premeditated?) Admiror, “I admire,” becomes Admiratur, “he admires.”

Figure 18

The shift in personal pronouns suggests two shifts in perspective. One shift is on the speaker’s part, as he consciously manipulates the canon of signs made by fingers and hands to perform a certain passion and thus becomes someone else: “I” becomes a dramatic character, a “he.” The other shift occurs on the spectator/listener’s part, as he admires–that deponent verb again—the speaker’s artifice: for the listener, the impassioned speaker is “he.” Chirologia, then, belongs to Vygotsky’s pre-verbal arena of thought-without-speech. Chironomia, with its calculated moves of turning words into gestures, belongs to the post-verbal arena of speech-without-thought, in the sense that “thought” has been reduced to words, and words have been reduced to gestures. The shift in pronouns is eloquent: “I”+verb is pre-verbal, “he”+verb is post-verbal. Why should that be so? The answer points to Lacan’s notion of words as an estrangement, as an imposition on bodily wholeness. It is verbal language that turns the first-person actor into a third-person subject. Along with the change in person in Bulwer’s second treatise comes a change in gender. The figures on the title page to Chirologia are female; on the title page to Chironomia, male. Is “natural” language to be read as female and “posited” language as male?

- “Nouns

and pronouns,” exclaims Will Summer in Thomas Nash’s play Summer’s Last Will and Testament, “I pronounce you

traitors to boys’ buttocks!” (Nash 114). For Shakespeare and his

male contemporaries the Verfremdungseffekt of language was

something they experienced through—and on—their bodies. To get

pronouns into schoolboys’ heads a schoolmaster needed to use other

parts of schoolboys’ bodies, the lower parts. It is the same parts

of the anatomy—the lower parts—that Hugh Evans has in mind in The

Merry Wives of Windsor when he tries to show off his pedagogical

handiwork to Mistress Page by quizzing her son William:

EVANS Show me now, William, some declensions of your pronouns.

I.e., id est. Memory is just it. What made pronouns so difficult for William Page and his fellow schoolboys was the fact that the pronouns he was learning and the rules that applied to them referred not to the English that they spoke without thinking about it but to the Latin that was beaten into them. If Latin was in the head (or supposed to be), English was in the buttocks. English grammarians before, during, and immediately after Shakespeare’s time had problems with pronouns, because in Vygotsky’s terms they thought in spoken English but spoke (for scholarly purposes at least) in Latin thought.

WILLIAM Forsooth, I have forgot.

EVANS It is “qui, que, quod.” If you forget your “qui”s, your “que”s, and your “quod”s, you must be preeches. Go your ways, and play; go.

MISTRESS PAGE He is a better scholar than I thought he was.

EVANS He is a good sprag memory (4.1.68-76 in Shakespeare 2005)

- William

Lily’s formulation of the rules of grammar and syntax, first

published in collaboration with Erasmus in 1513, became the model for

all English schools, thanks to royal proclamations by Henry VIII (in

1543), Edward VI (in 1547), and Elizabeth (in 1559) that in effect

made Lily’s explanation of the Latin language the explanation of language—English as well as Latin—for the entire

kingdom. In An Introduction of the Eight Parts of Speech (1543

edition) Lily defines “a pronoun” in terms that were repeated

verbatim by John Brinsley, Clifford Leech, and other pedagogues of

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—including, presumably, Hugh

Evans at Windsor in 1597 and Simon Hunt at the King’s New School in

Stratford-upon-Avon in the 1570s, when Shakespeare was likely a

student there. “A pronoun,” says Lily, “is a part of speech

much like a noun, which is used in showing or rehearsing” (sig.

B4v, spelling modernized). The catalogue of fifteen pronouns that

Lily proceeds to give, along with the categorizations and rules of

use that go with them, are all in Latin. Of the fifteen pronouns,

eight are “primitives, for because they be not derived of any

other.” These include ego, tu, sui, ille, ipse, iste, hic,

and is. Lily also calls them “demonstratives, because they

show a thing not spoken of before.” The other six pronouns—hic,

ille, iste, is, idem, and qui—are “relatives, because

they rehearse a thing that was spoken of before” (sig. B4v,

spelling modernized). Hence Lily’s basic definition of a pronoun as

a part of speech which is used in “showing” or “rehearsing.”

Like nouns, Latin pronouns possess number, case, gender, declension,

and person. These are the five things that have to be beaten into

schoolboys.

- Despite

Lily’s neat tables of declensions—structuralism avant la

letter—one has to note the ambiguity about hic, ille, iste, and is: they can be either demonstratives or relatives,

depending on the situation at hand. But the major opportunity for

deconstruction concerns “showing” versus “rehearsing.” These,

Lily assumes, are two separate activities. “I,” “thou,”

“one,” “that one,” “itself,” “that very one, “this,”

and “he,” to give the usual English translations of Lily’s

demonstratives, “show” someone or something not spoken of before.

It is curious that ego, “I,” should be one of these

someones or somethings in need of demonstration. By contrast, a

person or thing that has been spoken of before can be

“rehearsed” by using “this,” “that,” “that thing of

yours” or “that thing beside you,” “he,” “the same,”

and “who.” Really, I do hesitate to contradict Erasmus and Lily,

but it seems to me that what all pronouns do is “show.”

It’s well and good to distinguish persons and things that are being

referred to now and things that were referred to then,

but wasn’t that then once a now? You can’t have rehearsing without having once shown. We confront here

the kind of infinite regress familiar to us from deconstruction. What

all pronouns do at bottom, I would argue, is show. As Thomas

Blundeville puts it in The Art of Logic (1617), “This, or

That, and such like Pronouns, do point out a thing, as it were with

the finger, when proper names oftentimes do fail” (5, spelling

modernized). Hence the startling immediacy of “this man’s art”

and “that man’s scope,” of “featured like him, like him with

friends possessed.”

- In

Saussure’s terms, Lily and his successors, with their tables and

rules, were trying their damnedest to analyze langue. As long

as they stuck to Latin, they could pretty much do that. But the

distractions of parole could easily put them off track,

especially when they were trying to rationalize pronouns. Erasmus and

Lily may have assumed that they were talking about ego, but

really they were talking about ick and I. It was, after

all, Erasmus’s Flemish and Lily’s English, not Cicero’s Latin,

that needed free-standing pronouns like “I,” “thee,” “he,”

“she,” and “it.” A tension between langue and parole is played out on every page of Ben Jonson’s An English Grammar.

For the “grammar” part of his project Jonson is indebted to the

Latin education he received at Westminster School. In this endeavor

he proceeds deductively from the rules. Thus nouns in English are

reckoned to have number, gender, case, and declension just as they

would in Latin. But the “English” part of his project inspires

Jonson to pay careful attention to actual speech. For that, Jonson

proceeds inductively from numerous quotations. It is the parole of English speech, not the langue of Latin grammar, that leads

Jonson to the curious conclusion that the articles in English—a, an, and the—function as pronouns. Thus in Chapter III

Jonson explains the “syntax” of how a, an, and the are joined to substantives. “In these two pronouns,” he argues,

“the whole Construction almost of the Latins is contained”

(8:535, spelling modernized). Which is saying a lot, since Latin does

not use articles. Perhaps it is the prefix pro- in the term pronoun—literally, “before” or “in front of”—that

leads Jonson to treat articles as the paradigmatic case of pronouns.

- In

Shakespeare’s time people in England, France, Germany, and the Low

Countries could sometimes kill one another over pronouns, especially

pronouns that show. “Much divinity in pronouns,” Martin

Luther was often quoted as saying (Boys, sig. H2, spelling

modernized; Adams, sig. §§§4, spelling modernized).

The passage being cited–although one wonders how many of the people

doing the citing knew it directly—occurs in Luther’s commentary

on Galatians; in particular his commentary on verse 4, where Paul

refers to Christ, “who gave himself for our sins”—not

that man’s sins or this man’s sins but our sins and hence my sins. “We find very often in the scriptures,” Luther

observes, “that their significance consists in the proper

applications of pronouns, which also convey vigor and force”

(26:33-34).

- The

instance that could provoke murderous thoughts was the phrase “Hoc

est corpus meum”: the Latin Vulgate translation of the words

Christ is reported (in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke) to

have uttered at the Last Supper—“This is my body”—had found

its way into the liturgy of the mass by the twelfth century and

provided the occasion for sustained debate among Catholic and

Protestant apologists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The

demonstrative hoc, as Catholic writers liked to point out, is

neuter in gender and hence refers to corpus, the neuter word

for “body,” and not panis, the masculine word for “bread,”

which would take the masculine demonstrative pronoun hic. (All

a matter of hocus pocus, Protestant detractors said.) Nicholas

Sander in The Supper of Our Lord Set Forth According to the Truth

of the Gospel and Catholic Faith (Louvain, 1566) gives this

interpretation a classic statement. Christ’s “deed of taking

bread, and of blessing,” Sander argues, “showed his words to be

directed unto that which was in his hand, or lay before him (which

was bread before). It must needs be, that the pronoun this so

showed to his Apostles the thing already subject unto their eyes,

that much more it served to teach their understanding verily, this

which appeared to them bread to be in substance, at the ending of the

words, his own body” (sig. YY1v, spelling modernized). Protestant

polemicists like Daniel Featley in Transubstantion Exploded (1638) will have none of this: “it seems to be very absurd to say

that the pronoun this doth not demonstrate something present.

But our Lord took bread, and reaching it, said, ‘Take eat, this is

my body.’ He seems therefore to have demonstrated bread” (sig.

I5, spelling modernized).

- I wish to

embrace the Catholic argument. Hoc can refer, not just to the

thing in front of the speaker, but to the process through which that

thing acquires a name and comes to figure in speech. As Sander puts

it, “we teach the pronoun this to serve both to the eyes and

to the understanding of the Apostles: to their eyes, in pointing to

the form of bread which they saw; to their understanding, in teaching

that substance which was present under that they saw, to be his own

body straight when it was so named” (sig. YY1v, spelling

modernized). Hoc, that is to say, gestures toward a process—a

process by which thought becomes word.

- The OED states in more eloquent and precise terms what we heirs of Erasmus,

Lyly, and Jonson learned in grammar school: a pronoun is “a word

used instead of a noun substantive, to designate an object without

naming it, when that which is referred to is known from context or

usage, has been already mentioned or indicated, or, being unknown, is

the subject or object of inquiry” (OED, “pronoun,” a.)

Note the positions of “object” and “subject” in this

definition: a pronoun is regarded as something there, a

bounded entity, an object that stands in for another object. But the

prefix pro- is not so solid. What is that pro- and what

does it do to the -noun to which it is attached? As Bulwer and

Chris Garcia remind us, pronouns are implicated in actions. The Latin

word pronomen belongs to a class of constructions that all

involve a verb. Thus, a pro-consul was, originally, a person acting in the place of a consul. Similarly with pro-dictator, pro-gubernator, pro-praetor–and pro-nomen (OED, “pro-“, prefix[1], II.4). A pro-noun “acts in the place of” a noun. It may look like a

substantive, as if it names things, but in fact it works like

a verb: it does things.

- Among the

standard eight parts of speech, the one with which pronouns have the

most affinity is not, finally, nouns or verbs but prepositions. The

Latin pro- is cognate with the Greek πρó meaning forward,

before, in front of, earlier than (OED, “pro.,” n.[1], prep., and a., etymology). Pronouns don’t just name

substantives; they locate them. In that respect they function

as prepositions. According to Michel Serres in Angels and The

Troubadour of Knowledge, prepositions point up the conditionality

of knowledge. Objects of knowledge don’t just exist over there;

they exist in certain temporal and spatial relationships to the

knower. Prepositions, literally, pre-pose the knower’s

body. They position it before, both temporally and

spatially and implicate the body in ways of knowing the world that

are far more complicated than the subject/object binary implicit in

nouns, in the act of naming. In Serres’s formulation, “weaving

space, constructing time, they are the precursors of every presence”

(Angels 146).

- To

understand how this works, consider the prepositions in sonnet 29:

“in” (line 1), “out” (2), “with” (3), “upon” (4),

“like to” and “in” (5), “like” (6), “with” (8), “in”

(9), “on” (10), “like to,” “at,” and “of” (11),

“from” and “at” (12), “with” (14). Each of these

prepositions, in Serres’s terms, pre-poses “I” vis-à-vis

various other persons and things. “I” may weep, admire, and

triumph, but “I” does so in certain spatial and temporal

relationships. The most remarkable of these situations occurs in line

4:

VVHen in disgrace with Fortune and mens eyes,

I all alone beweepe my out-cast state,

And trouble deafe heauen with my bootlesse cries.

And looke vpon my selfe and curse my fate . . . (Shakespeare 1604: C2v-C3).Figure 19 shows how Chris Garcia manages that reflexive action:

Figure 19

We see him here in mid sequence, between projecting two looking fingers outwards toward the listener/viewers and turning those looking fingers upon himself. In that gesture he establishes the contingent nature of the speaker, located within his own body but reaching out in a gesture of inclusiveness toward the bodies of others. The preposition that seems most apt here is about, a combination of Anglo-Saxon be (by) + utan (outside), a movement “around the outside” (OED, “about,” etymology).

- What, in

this sense, is sonnet 29 about? Not about “myself,” “this man,”

“that man,” “thee,” and “they,” but about them all

vis-à-vis the red dot, the speaking “I.” Think about the

situation of the speaker with respect to the pro- in the

pronouns he invokes. Forward, before, in front of, earlier than: it’s

the pronoun that comes first. It’s the pronoun that is closer. The person or object being named is further away in

space and/or time. The pronoun occupies the middle distance. “He”

and “she” in Shakespeare’s sonnets hover somewhere in between

the speaker and the people to whom the speaker is referring. Think

then about the situation of the reader. In the cases of the “he”

and the “she” of Shakespeare’s sonnets, the reader never goes

the whole distance. The reader is left in the last of the situations

described in the OED’s definition of “pronoun,” a

situation in which the noun, “being unknown, is the subject or

object of inquiry.”

- Where,

then, should we locate the subject position in Shakespeare’s

sonnets? What name can we put to the space that the reading subject

occupies? Shakespeare gives us the phrase in line 10: “Haplye I

thinke on thee, and then my state … ”. The lines that follow

introduce a syntactical ambiguity that demonstrates how

speech-without-thought in sonnet 29 has not actually transcended

thought-without-speech. In the 1609 quarto printing the phrase “Like

to the lark at break of day arising” is put within

parentheses—marked off as a simile—so that there can be no doubt

about who or what is doing the singing at heaven’s gate. Not the

speaking “I,” not the lark, but “my state.” Chris Garcia

probably speaks for most readers of the poem in assuming that it is

the lark who is doing the singing, or perhaps the speaking “I” in

the guise of a lark. Thus Chris interprets the line as

bird/ wake / inspire/ chirp / sing / offer up / towards heaven.

Stephen Booth, as usual, wants to keep in play all three possible actors: “I,” “lark,” and “my state.” The general context and the common knowledge that birds fly, Booth observes “make any punctuation powerless to deny that state and lark are both singers and risers. However, both the Q punctuation and the line-end pause between arising and From carry a syntactically blurred image of the speaker’s state sending hymns aloft from the earth, sending up hymns to heaven” (Shakespeare 2000: 181). Katherine Duncan-Jones in the Arden Three edition uses italics to register mild surprise at the syntax: “Instead of importuning heaven, as in l. 3, the speaker, or his state, now praises God” (Shakespeare 1997: 29). The three iterations of the word “state” are central to Helen Vendler’s reading of the poem in The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. “State” is one of two key words, she observes, that resonate between the couplet and the rest of the poem (the other key word is “sings”), and it is the very word that encapsulates the speaker’s self-analysis, as he moves from the social world of “my outcast state” to the natural world of “my state,/ Like to the lark” and ends with “my state,” not to be compared with kings’, in the final line. This third iteration, Vendler proposes, incorporates the earlier two states, the social and the natural, and offers “an integrated model of the ‘whole’ world” (161).

- “State,”

I would agree, best describes the speaker’s situation–but in a

thoroughly physical, thoroughly grounded way. “State” has its

origins in the Latin verb stare, to stand. So “my state”

means, physically as well as psychologically and ethically, “how I

stand.” Sonnet 29 is one of the citations in the OED for

“state” in the more abstract sense of “A combination of

circumstances or attributes belonging for the time being to a person

or thing” (OED, “state,” n., I.1.a). But “state”

is also “A condition (of mind or feeling); the mental or emotional

condition in which a person finds himself at a particular time”

(I.2.a). “My state” is what I find when I “look upon myself.”

As such, “state” gets us closer to the dynamics of the speaker’s

situation in sonnet 29 (and in the sonnets in general) than does the

rigid (if unstable) geometry of “I,” “you,” “he,” “she,”

and “we.” Above all, “state” reminds us that thought is not

just words but bodily gesture, an extension of the speaker’s body

into ambient space. The relationship of “I” to “thee,” “he,”

and “she” is a matter of “in,” “out,” “with,” “at,”

“from,” and “like to.”

- With

respect to the body, “I,” “he,” and “thou” merge into

that useful but now rarely heard pronoun “one.” “One” purports to be third person, but it functions as an

amalgam of “I” and “you.” It exists somewhere in between “I”

and “you.” It implies mutual understanding. It pointedly excludes

“them.” How should one read a Shakespeare sonnet? By realizing

that difference-marking might not be the beginning of meaning-making.

By embracing middle voice. By attending to pronouns. By assuming the

subject position of “one.”

Works Cited

- Adams, Thomas. The Happiness of the Church. London: John Grismond, 1619. Print.

- Benveniste, Emile. Problems in General Linguistics. Trans. Mary Elizabeth Meek. Coral Gables, FL: U of Miami P, 1971. Print.

- Blundeville, Thomas. The Art of Logic. London: William Stansby, 1617. Print.

- Boys, John. An Exposition of All the Principal Scriptures Used in Our English Liturgy. London: Felix Kingston, 1610. Print.

- Bulwer, John. Chirologia: or the Natural Language of the Hand and Chironomia: or the Art of Manual Rhetoric. Ed. James W. Cleary. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP, 1974. Print.

- Crooke, Helkiah. Microcosmographia, or A Description of the Body of Man. London: William Jaggard, 1615. Print.

- Damasio, Antonio R. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt, 1999. Print.

- Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Corrected edn. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1997. Print.

- Featley, Daniel. Transubstantiation Exploded. London: G. Miller, 1638. Print.

- Fodor, Jerry A. The Language of Thought. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1975. Print.

- Jonson, Ben. The English Grammar. In Ben Jonson. Ed. C. H. Herford, Percy Simpson, and Evelyn Simpson. Vol. 8. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1947. Print.

- Lily, William. An Introduction of the Eight Parts of Speech. London: Thomas Berthelet, 1543. Print.

- Luther, Martin. Works. Ed. Jaroslav Pelikan and Walter A. Hansen. Vol. 26. St. Louis, MO: Concordia, 1963. Print.

- McNeill, David. Gesture and Thought. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2005. Print.

- Nash, Thomas. Summer’s Last Will and Testament. In Selected Writings. Ed. Stanley Wells. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1965. Print.

- Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008 and earlier. Web. January 2009.

- Park, Katherine. “The Organic Soul.” In The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy. Charles B. Schmitt, gen. ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988. Print.

- Quintilianus, Marcus Fabricus. Institutio Oratoria. Trans. H. E. Butler. 4 vols. London: Heinemann, 1921. Print. Loeb Library.

- Sander, Nicholas. The Supper of Our Loard Set Forth According to the Truth of the Gospel and Catholic Faith. Louvain: Johannes Foulerum, 1566. Print.

- Saussure, Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics. 1916. Ed. Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye. Trans. Wade Baskin. New York: Philosophical Library, 1959. Print.

- Serres, Michel. Angels: A Modern Myth. Trans. Francis Cowper. Paris: Flammarion, 1995. Print.

- ---. The Troubadour of Knowledge. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1997. Print.

Figure 16