Subject Access Through an Emblem Portal: A Common Standard for Students and Scholars

Thomas

Kilton

University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

t-kilton@illinois.edu

Thomas Kilton, “Subject Access Through an Emblem Portal: A Common Standard for Students and Scholars,” Emblem Digitization: Conducting Digital Research

with Renaissance Texts and Images, ed. Mara R. Wade. Early Modern

Literary Studies Special Issue 20 (2012): 5. <URL: http://purl.oclc.org/emls/si-20/WADE_ Kilton_EMLS.htm>.

1. At the working conference at the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, my paper addressed issues concerning the provision of adequate access points by our OpenEmblem Portal sites to attract a wider range of library users, including students as well as scholars not particularly versed in iconography, symbolism, and foreign languages.[1] The focus there was on better design of homepages, clearer definitions of the emblem, increased search access points, and the standardized use of data elements. While these provisions were essentially satisfied by the presentations of Stephen Rawles on the Spine[2] and Hans Brandhorst on IconClass,[3] researchers working according to OpenEmblem guidelines should be now encouraged to employ many of the data elements that the Spine tags as optional.[4] In any case, if some agreement can be reached on which data elements and access points are commonly desirable, perhaps more thought should be given to who the targeted user groups are and what their information seeking behaviors might be. My perceptions are no doubt emboldened by the current trend in North American academic librarianship of what used to be called bibliographic instruction and now is called information literacy. While the over-emphasis given this activity in today’s academic setting might seem overstated, this activity does indeed have merit, and surely within the context of accessibility to the veritable science of emblems.

Emblem sites in the research library context

2. As an academic librarian it is fascinating to observe the place digital emblem sites occupy in the current conceptual framework of research libraries. Two observations deserve further attention: 1) the partnering of international projects as to truly approximate the concept of library as laboratory, and 2) their realization of the concept of space as library. The enhancements and standards these sites should consider, in order to render them more useful and more accessible for a wider range of users from the neophyte student to the scholar immersed in emblem analysis and interpretation, contextualize the discussion.

3. Few bodies of recorded knowledge conceivably offer the digitization team of scholar, information technologist, and librarian more rewarding opportunities to provide their clientele with remote graphic and subject access to dispersed collections of thematically related materials than does emblem literature. Owing to the intricate nature of this genre, coordinated teamwork is particularly necessary to the tasks of selecting, digitizing, analyzing, and assigning descriptors, topoi, and themes. Although the contributions of the scholar and the IT specialist are often more clearly delineated than that of the librarian, the role of the librarian as developer and curator of collections, imposer of bibliographic control over them, advocate for resources to purchase and preserve them, and presenter of library instruction, i.e., information literacy, is not insignificant. Of course, the functions of librarian, IT specialist, and scholar are not mutually exclusive of one another, as the project teams for emblem studies reveal.

Realizing the concept of library as laboratory

4. As Carole Palmer observes, “the analogy of the library as the laboratory of the humanities has always been an exaggeration.” It is worth digressing here to note that to many librarians this concept has become offensive, particularly on some campuses when, on major occasions, such as the dedication of a major volume, tall male campus administrators with wavy white hair hold stentorian speeches citing the library as the “heart of the campus, “ the “jewel in the crown,” “the laboratory for the humanities” and “the reason Maude and I came here in 1969,” only to ignore this jewel’s basic needs following these ceremonies. Palmer observes that “...for most humanistic scholars, it has been rare to find the necessary materials for a research project amassed in one place, as they are in a laboratory setting.” She concludes significantly that “thematic research collections in the form of digitized resources come closer to this ideal. Where in the past scholars produced documents from source materials held in the collections of libraries, archives, and museums, they are now producing specialized scholarly resources that constitute research collections.”[5] In other words, by enabling searches across a number of library collections with thematically related materials from diverse libraries, archives, and museums, current technology does indeed provide for an approximation, if not an ideal, of the library as laboratory. As the sites participating in the OpenEmblem Portal increasingly become searchable across a common interface, they are indeed embodying the concept of library as humanities laboratory.[6] Nonetheless, there are some essential features that academic websites, such as those for emblem studies, should start including in order to further develop this laboratory. These features might include, for example, an up-to-date listing of secondary criticism and reference sources for emblem studies, encompassing exhaustive references to major journals, articles, books, chapters in books, catalogs, bibliographies, and Internet sources. Annotated lists of reference handbooks, such as dictionaries of symbols in religion, folklore, and classical mythology, as well as such standard works as Praz and Henkel and Schöne. Although a superb iconographic indexing thesaurus such as Iconclass provides students or scholars with appropriate descriptor terms as well as themes and topoi, the value of additional supplementary works on symbols and allegory in art and literature to assist the user with interpretation cannot be overstated.

5. In the context of this research “laboratory,” the OpenEmblem Portal constitutes an ideal opportunity to bring a wealth of heretofore hidden knowledge to students and scholars across the humanities and, to a perhaps somewhat lesser degree, the social sciences, regardless of their previous knowledge of iconography, symbolism, and foreign languages.[7] But to do this, the mutually agreed upon common standards for these projects, as expressed in the Spine, must be exploited to the limits of their boundaries.

Realizing the concept of space as library

6. Since the advent of the Web and distributed digitized collections open to universal access, the concept of “library as space” has given way to the concept of “space as library,” a concept become mantra for library space planners at academic libraries across North America who seek to render the entire campus a “library.” The existing emblem sites, particularly those partnering with one another to provide common search structures and data elements, also embody the concept of space as library, or even space as laboratory. With the availability of remote access to these digital artifacts, the role of the librarian as curator of this laboratory is changing in two ways. First, decisions to acquire specific emblem books for the local library are naturally affected by whether or not other libraries in digital partnerships own those same titles. Second, for those libraries which have embarked on emblem digitization, the inducement of the librarian, whether curator of rare books or subject specialist, to become more engaged with emblem books has increased, in part owing to the greater access of these materials for faculty and students as an outcome their online availability through digitization. Even some campus administrators now know what an emblem book is, or at least have heard of emblem books. The availability of sufficient search access points will attract not just the fleeting attention of users, but also stimulate active use stimulated of these rare materials.

Maximizing subject and other access elements

7. Presently some major library collections of emblem literature are cooperating in the creation of aportal (e.g. The Open Emblem,) common thesauri (e.g. IconClass and Arkyves),[8] and common metadata categories and search fields (e.g. the Spine). These standards are recommended in a constructive way that helps to determine best practices. But the whole issue of best practices begs the question of just who the users are that these digital library partnerships have in mind. Questions must be posed concerning these potential users’ information-seeking behaviors. To encourage wider use of digital emblematica for research as well as teaching purposes, projects must utilize many more of the headings that the Spine categorizes as “optional,” including those for the translation of subscriptio and commentatio, those for authorial and editorial textual notes, and those for textual and pictorial motifs. As more sites digitize entire emblem books from cover to cover, as does the Herzog August Bibliothek, and, the entries for these books must be linked to their full catalog records, again, a superb feature of the Herzog August Bibliothek. Michael Gorman, the co-editor of AACR2 (Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules) and past President of the American Library Association, has often asserted in his writings that cataloging is the foundation of all librarianship. If this is true, then every digital project that aspires to constitute a “digital library” ought to concern itself with cataloging. But few do. Therefore, in addition to providing high quality images of the emblems and rendering them searchable, serious projects should include full rare book descriptive catalog records to note format, collation by signature, pagination, foliation, imperfections, and provenance marks. If students as well as scholars not particularly skilled in foreign languages or conversant with the Bible and Classical mythology comprise the target audience, projects should do more than simply present the scanned emblem in the digital environment, and perhaps in addition to a browseable list descriptors, take steps further to assist users in interpreting the meanings of the emblems. In many cases even advanced students of iconography and literature need some interpretive assistance if the emblems are to make any sense to them at all. This entails assisting them in interpreting the subscriptio as well as the pictura of an emblem.

8. Some emblem sites already feature headings categorized as optional by the Spine and which can greatly assist the non-experienced student or scholar. The Memorial University of Newfoundland’s Alciato’s Book of Emblems translates the subscriptiones into English and arranges them thematically,[9] while at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, the project “Digitalisierung von ausgewählten Emblembüchern” provides a German commentary on many of the subscriptiones, particularly those in Latin.[10] Some emblem web sites provide for searching by descriptors and/or themes (which the Spine calls textual and pictorial motifs and themes), or they supply translations of their mottos, also included in the Spine. The Emblem Project Utrecht analyzes picturae via descriptors as well as topoi and themes.[11] With time, it is to be hoped that all of emblem projects will have the resources and time either to translate their subscriptiones or to provide commentary on them. The provision of subject access to the elements of the picturae and mottoes, while often enabling the user to extract some sense of an emblem, is obviously not always sufficient for the full comprehension, not to mention appreciation and enjoyment of an emblem. The subscriptio often provides the key to understanding the emblem. The whole issue of translation, of course, begs the question as to what language or languages we should be translating into. The question is whether English serves as the current lingua franca, or if it would be best for each site to translate the subscriptiones into its own vernacular language.

9. The following spider emblems illustrate the point that knowledge of a motto, descriptors in a pictura, and even themes and topoi are not sufficient to convey the true meaning of an emblem if the subscriptio cannot be understood because of a lack of foreign language skills on the part of the reader. And generally speaking, relatively few scholars today are adequately conversant in the languages of Renaissance Europe, leave alone Latin, to understand the subscriptiones without the aid of translation and interpretation.

10. The following three emblems involving the symbolism of spiders illustrate the importance of translating the subscriptio or providing a commentary for the student or scholar not adept at translating Latin or Renaissance German to understand the emblem fully.

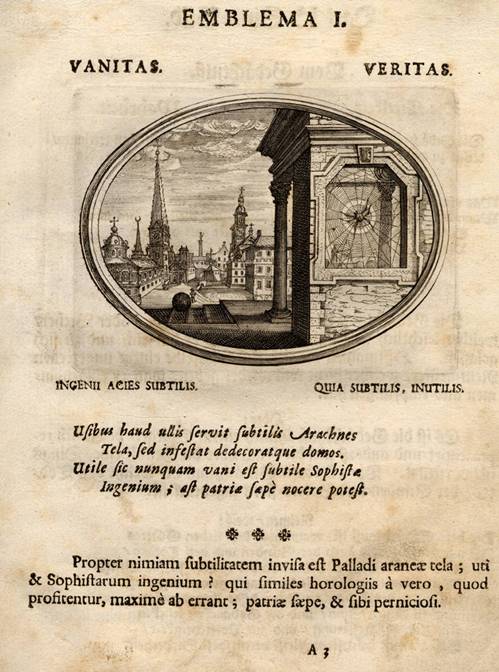

Antoine de Bourgogne, Mundi Lapis Lydius. Oder: Der Welt Probier-Stein. Augsburg: Lotter, 1712, Emblem 1. Image courtesy of Emblematica Online, University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign and Herzog August Biblothek, Wolfenbüttel.

11. The first emblem is taken from Antoine de Bourgogne, Mundi lapis Lydius, oder, Der Welt Probier-Stein: das ist, Emblematische Sitten-Lehren at the University of Illinois emblem site.[12]

12. In this mysterious and fascinating emblem, the inscriptio consists of two mottoes: “Ingenii subtilis, inutilis’ (Subtle sharpness of mind is useless) and “Quia subtilis, inutilis” (Because it is subtle, it is useless). The pictura features a large spider hanging in a well-constructed web in an open window of a building. The background depicts a cityscape with church towers and possibly a mosque. The early version of Emblematica Online funded by a Transcoop grant from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation provided a sample of what this metadata could look like.[13] The online descriptors provided were: cityscape, spider, spider web, and web. The assigned topos was: “spider web as irrelevant cleverness” and the assigned theme “Cleverness alone is of no real value.” This metadata offers users a vague sense of the symbolism attached to the spider (irrelevant cleverness), but without a knowledge of the subscriptio and following commentatio, the meaning remains overly vague. While Iconclass notations now replace the search terms in the new portal, this early research demonstrates my points well. A vernacular paraphrase or translation of the subscriptio would reveal that the subtle spider’s web serves hardly any practical use, but rather it infests and dirties buildings, and, that similarly, the subtle mind of the sophist is also not useful, but rather harmful to his country. The commentatio further explicates the meaning of the subscriptio. It decries the Sophists’ opposition to the truth, comparing them to clocks with their irregular performance. Seen as deceitful, the subtle sharpness of the Sophists’ mind is compared with the clever deceit of the spider’s web. Perhaps to the seventeenth-century Jesuit author, the vanity of Classical learning with its sophistic pagan rhetoric is being contrasted with what he views as Christian truth and can be embodied in the spider and the religious towers in the cityscape.

13. Despite aid from metadata supplied by the assigned topos and theme, the basis for the theme or moral conveyed in this emblem—cleverness alone is of no real value—remains inaccessible without access to the language of the subscriptio and commentatio.

14. The next two emblems are both taken from Conrad Meyer’s Fünff und zwanzig Bedenkliche figuren mit Erbaulichen Erinnerungen, Dem Tugend und Kunstliebenden Zu gutter gedechtnus in Kupffer gebracht from the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.[14]

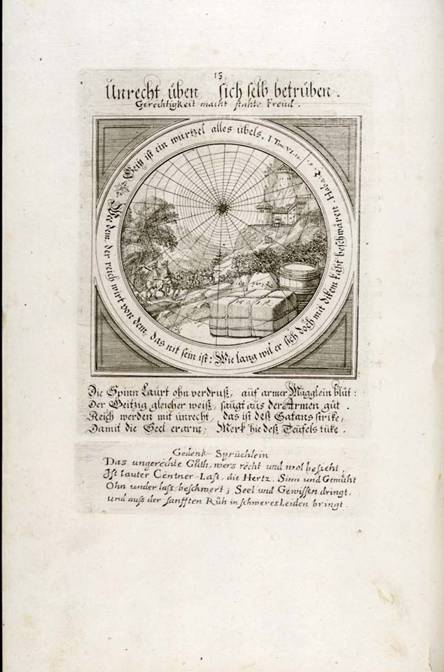

Conrad Meyer, Fünf und zwanzig Bedenkliche Figuren mit erbaulichen Erinnerungen: Dem tugend und Kunstliebenden Zu gutter Gedechtnus in Kupffer gebracht. Zürich, 1674, Emblem 15. Image courtesy of Emblematica Online, University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign and Herzog August Biblothek, Wolfenbüttel.

15. The inscriptio here “Unrecht üben, sich selbst betrüben; Gerechtigkeit macht stahte [stete] Freüd” states that if you perform injustice, you will deceive yourself; Justice makes joy. Words on the border of the pictura state that meanness is the root of all evil, and woe to him who gets rich off that which is not his. The subscriptio describes the spider lurking without remorse for the blood of the poor insect. The mean person knows how similarly to suck good from the poor. To become rich unjustly is the way of Satan, and the commentatio amplifies this notion. The pictura features a huge spider web in front of a landscape with what appear to be soldiers on the way to a castle. Bundles of goods and a vat appear to be their booty. Here again, without a knowledge of the subscriptio, the meaning of the emblem is obscure, and would remain obscure, even with the provision of a topos, such as “spider as evil” or “spider as parasite,” since the spider’s opportunism or parasitical nature are expressed by the subscriptio alone. The allegory of Justice is an amplification of the text and image.

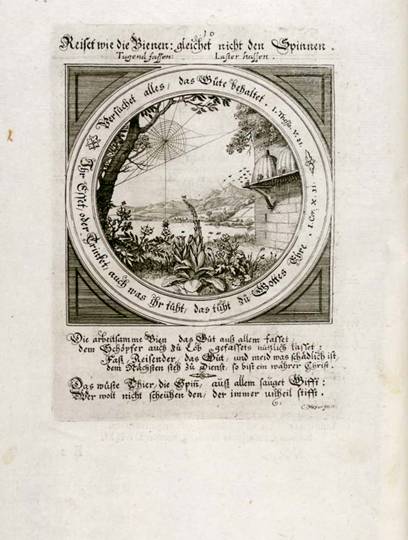

Conrad Meyer, Fünf und zwanzig Bedenkliche Figuren mit erbaulichen Erinnerungen: Dem tugend und Kunstliebenden Zu gutter Gedechtnus in Kupffer gebracht. Zürich, 1674, Emblem 10. Image courtesy of Emblematica Online, University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign and Herzog August Biblothek, Wolfenbüttel.

16. The final example portrays the familiar image of the spider and the bees. Here the spider is again linked with evil. The motto states: "Reiset wie die Bienen, gleichet nicht den Spinnen. Tugend fassen, Laster hassen" (Travel like the bees; don’t resemble the spiders. Seize virtue; hate vice). The pictura features a spider suspended in a web, and to the side bees swarm around two beehives. The subscriptio, however, contrasts the spider to the industriousness of the bee in making good use of everything and being useful to others, as a true Christian is. The spider, however, which injects poison into its victims, is a devastating insect. The provision of a theme or topos here would, of course, help to elucidate the meaning of the pictura and subscriptio (perhaps “spider as parasite,” or “bee as a Christian”), but, the reason for the contrast as given in the subscriptio remains inaccessible to a reader not fluent in seventeenth-century German.

17. A first step in the interpretation and indexing of emblems is to choose a limited and workable number of them to translate which are ideally representative of select topoi, such as the “crane as vigilance” or the “oak and the reed,” in order to showcase these representative emblems for a wide range of users.

18. These observations are worth for consideration to achieve common purposes in serving emblem users, which, after all, is the reason for an endeavor such as the OpenEmblem Portal. Finding time, money, and expertise is not easy, and it is perhaps not essential to accomplish the ideal immediately. The value of international collaboration for the purpose of expanding the appeal of emblem sites and portals to a wide range of scholars and students can not be overstated.

Notes

[1] Kilton, 107-114.

[2] Rawles, 19-28.

[3] Brandhorst, 29-44.

[5] Palmer, p. 348.

[6] http://emblematica.grainger.illinois.edu/ . The portal, part of the bilateral digitization project of the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, and the University of Illinois, will be fully functional in 2012.

[12] Augsburg: Johann Jacob Lotter, 1712. http://libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu/OCA/Books2010-01/mundilapislydius00bourg/ In the course of 2012 all emblem books digitized at the University of Illinois will become searchable at the Emblematica Online Website when the portal goes live.

[13] See, for example, the discussion by Andrea Opitz in this volume.

[14] Zürich: Conrad Meyer, 1674. http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/xb-4f-344/start.htm

Works Cited

All websites are cited in the Notes.

- Brandhorst, Hans. “Using Iconclass for the Iconogrpahic Indexing of Emblems,” in: Digital Collections and the Management of Knowledge: Renaissance Emblem Literature as a Case Study for the Digitization of Rare Texts and Images, ed. Mara R. Wade. Salzburg: DigiCULT, 2004. 29-44. http://www.digicult.info/pages/special.php

- Henkel, Arthur, and Schöne, Albrecht. Emblemata: Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 1967.

- Kilton, Thomas. “Emblematica Online: The User’s Perspective,” in: Digital Collections and the Management of Knowledge: Renaissance Emblem Literature as a Case Study for the Digitization of Rare Texts and Images, ed. Mara R. Wade. Salzburg: DigiCULT, 2004. 29-44. http://www.digicult.info/pages/special.php

- Palmer, Carol E., “Thematic Research Collections,” A Companion to Digital Humanities, ed. Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, and John Unsworth. Oxford, MA: Oxford Publishing, 2004, pp. 348-365. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companion/index.html

- Praz, Mario. Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Roma: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 1964-74.

- Rawles, Stephen. “A Spine of Information Headings for Emblem-Related Electronic Resources,” in: Digital Collections and the Management of Knowledge: Renaissance Emblem Literature as a Case Study for the Digitization of Rare Texts and Images, ed. Mara R. Wade. Salzburg: DigiCULT, 2004. 19-28. http://www.digicult.info/pages/special.php