Punctuation as Configuration; or, How Many Sentences Are There in Sonnet 1?

William H. Sherman

University of York, UK

bill.sherman@york.ac.uk

- Shakespeare's Sonnets, produced in the last great age

of manuscript circulation, have long enjoyed a special relationship with the

printing press. In academic debates about Shakespeare as author for page versus

stage, the poems have often served to suggest that he was not averse to playing

the part of the literateur or to seeing his texts in print. And in the

modern Fine or Private Press movement, the Sonnets have become what Andrew

Hoyem (of San Francisco's Arion Press) describes as "the ultimate

'chestnut' of pressbooks," bringing together the most beautiful poems in

the English language with the finest in typographic style. In 1997, Hoyem overcame

his reluctance "to add yet another volume to the sagging shelf of

Shakespeare's poems in this form" and produced an exquisite edition,

prepared by Helen Vendler, printed in newly cast type, and bound in red leather

and floral brocade.

- It is hardly surprising, then, that when

master-printer Jonathan Finegold chose the auspicious year of 2009 to open his

New Albion Press, the first book he produced was the Quatercentenary Edition

of Shakespeare's Sonnets (Figure 1)--issued in a standard version of

seventy-five numbered copies and a deluxe version of twenty-six lettered

copies, hand-printed on laid paper and bound in terracotta goatskin stamped

with real gold. Anniversaries are particularly resonant moments of

(re)configuration, and Finegold's edition marks a series of milestones in the

textual life and afterlife of Shakespeare. The dates of publication on the

title-page (MDCIX - MDCCCCIX - MMIX) link the edition to not one but two

earlier books: as Finegold explains in the colophon, it was printed to

celebrate "the four hundredth anniversary of the first printing of

Shakespeare's Sonnets and the one hundredth anniversary of the edition printed

by T. J. Cobden-Sanderson at the Doves Press" (successor to William

Morris's Kelmscott Press and producer of some of the twentieth century's most

beautiful books).[1]

Finegold's volume is as much a Centenary as a Quatercentary

edition, then, and, in form and function, it may owe more to Cobden-Sanderson

than to Eld or even Shakespeare.

Figure 1: THE TITLE-PAGE OF THE QUATERCENTENARY EDITION OF SHAKESPEARE'S SONNETS (NEW ALBION PRESS, 2009). Courtesy the Folger Shakespeare Library and the New Albion Press.

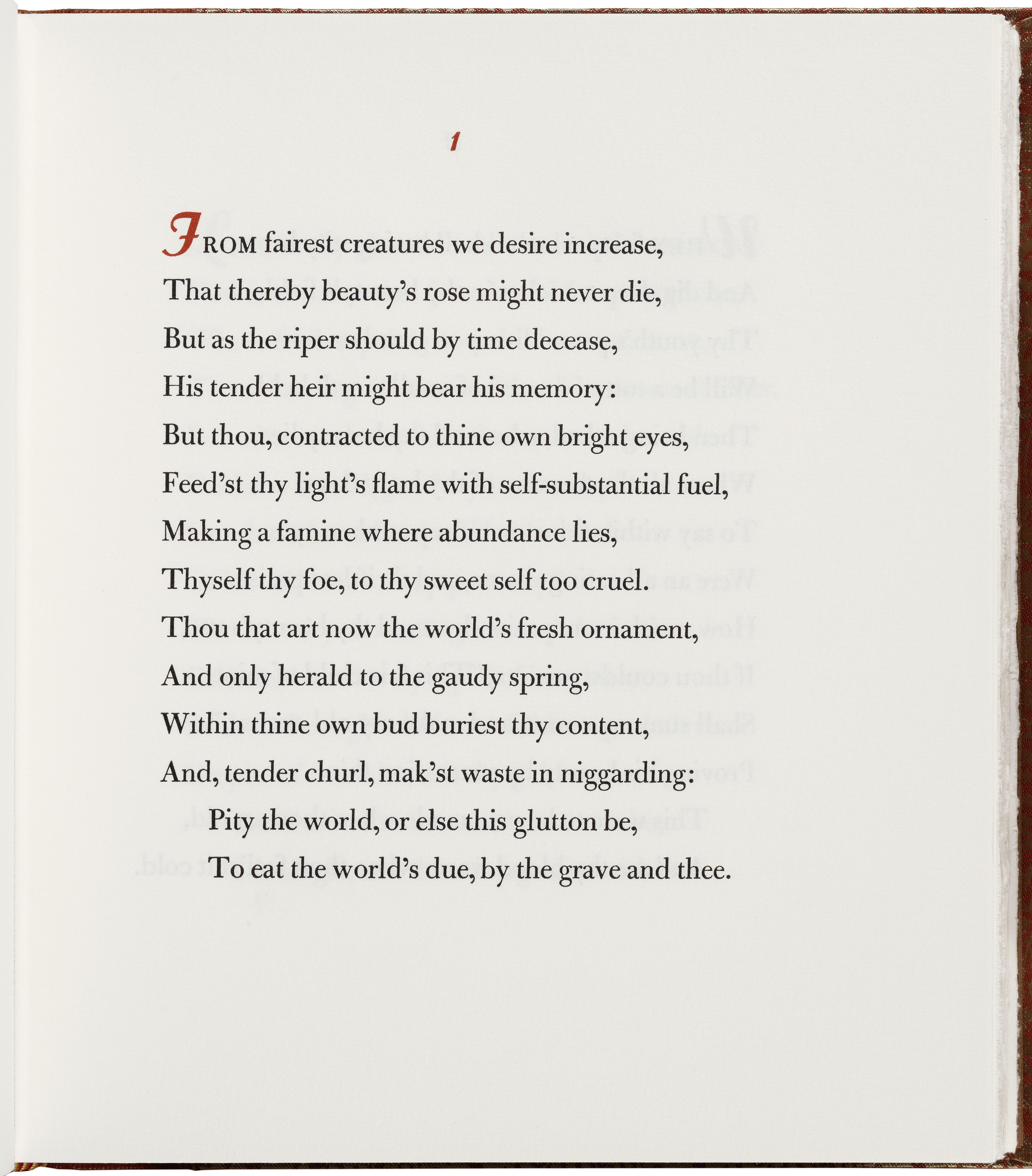

- A quick glance at the opening sonnet in the New

Albion and Doves Press editions [Figures 2 and 3] reveals that the former is,

in effect, a character-for-character type facsimile of the latter--no mean feat

since the entire Doves font was thrown into the River Thames by

Cobden-Sanderson in 1917, bringing an abrupt end to an increasingly unhappy

partnership (Cable, Garfield, Tidcombe). Using Torbjörn Olsson's reconstructed

type, Finegold has carefully followed every aspect of Cobden-Sanderson's

distinctive design, seen at its most striking in Sonnet 1. In a major departure

from Eld's original presentation [Figure 4], the first two poems are given

their own pages and set in all-caps, in a style associated with monumental

inscriptions.[2]

The final word or phrase in every line is wrapped around and indented to the

middle of the page, giving the block of text a dramatic new shape. The density

of the right side enhances the open spacing of the openings of lines on the

left; and the column running down the middle is balanced by the page-long stem

of the initial "F"--stretched from the squat two-line capital in the

1609 Quarto into an elegant marginal ornament, designed by Edward Johnston and

cut by Noel Rooke and Eric Gill--that both frames the whole poem and marks its

constituent parts. The tapered cross-bar (which literally bears the

"memory" in line 4) and two pairs of diamonds (like colons turned on

their side) divide the three quatrains that lead, in the typical Shakespearean

sonnet, to a final rhyming couplet.

Figure 2: SONNET 1 IN THE QUATERCENTENARY EDITION OF SHAKESPEARE'S SONNETS (NEW ALBION PRESS, 2009). Courtesy the Folger Shakespeare Library and the New Albion Press.

Figure 3: SONNET 1 IN THE TERCENTENARY EDITION OF SHAKESPEARE'S SONNETS (DOVES PRESS, 1909). Huntington Library RB 607694, the copy given by Cobden-Sanderson to Furnival. Courtesy the Huntington Library.

Figure 4: SONNET 1 IN SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (1609). Courtesy the Folger Shakespeare Library.

- While Finegold follows his typographical model

with exceptional fidelity, he does introduce a few touches of his own. The most

conspicuous change on this page is the printing of the initial F in red rather

than black, a move that makes its form more vivid but sacrifices

Cobden-Sanderson's clear distinction between poem and title. A far more

significant modification, apparent in virtually every line of every poem, is

the modernization of the spelling and punctuation. Finegold's emendations make

for diction and syntax that are easier, to be sure, on the modern eye. For

instance, line 12's "AND TENDER CHORLE MAKST WAST IN NIGGARDING"

becomes "AND, TENDER CHURL, MAK'ST WASTE IN NIGGARDING": the added

commas give readers extra cues that will help them to parse the line. Likewise,

Finegold removes a comma at the end of line 9 that is strictly superfluous

since it separates two descriptions of the same person. But he makes some

larger changes that ought to give us pause for thought--including the editing

out of what we might call the "serial colon," a feature that breaks

modern rules but turns out to be a pervasive feature of pre-modern punctuation,

particularly in passages where the speaker is pausing for thought, for breath,

or for effect (Sherman). Eld and Cobden-Sanderson end all three quatrains with

a colon, making the entire sonnet one complex sentence with three linked

segments leading to the couplet's closing exhortation. Finegold changes all

three colons to full stops, transforming the sonnet into a sequence of four

more or less discrete sentences.

- Given Finegold's evident commitment to the spirit

and the letter of the 1909 design (with its evident commitment to the spelling

and punctuation of the 1609 printing), we may be surprised by his willingness

to take an editorial decision that has such sweeping implications for the way

the poems look and sound. Cobden-Sanderson himself would have been puzzled by

his protégé's pointing since he had first embraced and then rejected a

modernized text--at considerable cost and in no uncertain terms. When the Doves

Press started work on the Tercentenary Edition in the summer of 1909,

Cobden-Sanderson found the work of repunctuating the Sonnets "an

engrossing and captivating occupation," as he had done when printing his

modernized Hamlet earlier that year (Tidcombe 166). But halfway through

the job, with many pages of paper and vellum already printed, he began to lose

faith. He paid a visit to the great philologist and Shakespeare scholar F. J.

Furnivall, who lived down the street, and--against his stern advice--resolved

to start again from scratch.[3]

In a lengthy letter to The Times, published on 26 October 1911 and

issued separately as a Doves Press chapbook a year later, Cobden-Sanderson

explained his change of heart:

When I undertook the reprint of Shakespeare's Sonnets, thinking that for so exquisite a form of poetry the punctuation should be as exquisite, I decided to make an exception to my rule of following the text and to revise what had superficially seemed to me arbitrary and haphazard in the punctuation of the original. I accordingly revised the punctuation of the 1609 edition, sonnet by sonnet; & a fascinating & alluring balancing of nice probabilities I found it to be: but as I proceeded I found two other & more important things, first, that slowly, like the coming on of night, I was changing the whole aspect of the Sonnets, and, secondly, that the original punctuation had a method in its seeming madness.... I therefore cancelled all the sheets I had already printed, both vellum and paper, and began the edition over again, keeping, with few exceptions, punctiliously to the punctuation, and to all other characteristics, of the original (Cobden-Sanderson, 1-2).[4]

Cobden-Sanderson's emphasis on "original" forms and conditions may now strike us as naive; but it was very much in keeping with the cultural nostalgia of the Arts and Crafts movement, and largely untroubled by the later scholarship (bibliographical and philosophical) that would challenge our faith in access to Shakespeare's original or authentic texts. What is more surprising here is the sense that modernization may bring darkness rather than light to the Shakespearean poem, obscuring rather than illuminating its essential structure and style.

- For Finegold, the opposite is true. Enlisting the

support of "the best recent scholarship as to the spelling, punctuation,

and meaning of the Sonnets," he suggests that the original punctuation

creates an unnecessary obstacle to the modern readers who will use his book,

one that gets in the way of "the flow of the poetry" (Finegold).[5] Finegold is following the pattern

established by virtually every major current edition--from Private, Trade or

Academic presses.[6]

The Folger Library edition, like Finegold's, changes all three colons to full

stops, while those of Stephen Booth (Yale) and Katherine Duncan-Jones (Arden)

keep only the first.[7]

Helen Vendler (Harvard/Arion), Colin Burrow (Oxford) and G. Blakemore Evans

(Cambridge) opt for alternating colons and periods [Figure 5], which retains

much of the rhetorical complexity of the original while conforming to modern

conventions. Furthermore, their version makes the first eight lines a single

sentence-level unit while also linking the final six.

Figure 5: SONNET 1 IN VENDLER'S ARION PRESS EDITION (1997). Courtesy the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Arion Press.

- While none of these editors comments directly on

their choice of punctuation, readers familiar with the history of the sonnet

will realize that more is at stake in these numerical patterns than the

relative strength of the links between independent clauses or the relative

length of line-end pauses. The Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet adapted by

Shakespeare and his English contemporaries is distinguished by a two-part

structure of eight-line octave and six-line sestet. And while the

"primary structure" of Sonnet 1, according to Vendler, signals a

change after the first four lines (from "desirable" to

"actual" and from first-person plural to direct address), she

observes that "the ghost of the Italian sonnet can be said to underlie all

the sonnets in [Shakespeare's] sequence" and suggests that in cases like

this one there is a "shadow sonnet...behind the sonnet we are

reading" (49-50). The 1609 punctuation keeps both sonnet forms open, though

it requires hard work by readers to make their way through them; the pattern

chosen by Finegold and others makes the reader's job easier, but leaves the

ghost of the Italian sonnet in the shadows.

- There are, in other words, various argumentative,

rhetorical, and generic structures at work in Shakespeare's sonnets, which can

be enhanced or effaced by changes in punctuation. This does not necessarily

mean that Eld and Cobden-Sanderson got it right and that Finegold et.

al. got it wrong, but it does suggest that punctuation marks are more

complex and consequential than we tend to imagine, and prompts us to ask a

series of questions: What kind of punctuation does the best job of giving

modern readers access to early modern texts? Whose punctuation is preserved in

editions like Eld's 1609 Sonnets? What was the function of a colon in

Shakespeare's day and what, for that matter, was a sentence?

- The problem of punctuation is by no means

exclusive to the Sonnets. While the play of commas, colons and full stops may

be more concentrated in the limited space of a sonnet, the existence of

multiple versions and the extra dimension of cues for theatrical performance

make the interpretive challenges even more vexing for readers and actors of

Shakespeare's drama. And yet, despite the obvious importance of these questions

for the sense we make of Shakespeare, they have rarely been asked. "It is

common practice at the present day," Percy Simpson observed in 1911,

"to treat the punctuation of seventeenth-century books as beneath serious

notice; editors rarely allude to it, and if they do, they describe it as

chaotic and warn the reader that they have been driven to abandon it" (7).

A century later, Jonathan Crewe argued that we still have not moved beyond the

attitudes of one of Shakespeare's 18th-century editors, Samuel Johnson, who

explained that, "In restoring the authour’s works to their integrity, I

have considered the punctuation as wholly in my power; for what could be their

care of colons and commas, who corrupted words and sentences? Whatever could be

done by adjusting points is therefore silently performed...." As we enter

the twenty-first century, Crewe observed, "repunctuation, often silent,

remains a prerogative assumed by those editing Shakespeare’s texts for the mass

market and even for fairly restricted academic circulation" (Crewe 23).

- Almost every other issue involved in presenting

early modern texts in modern forms--including the problem of inconsistent

speech prefixes and absent stage directions, the challenge of multiple texts,

and the presence of other authors and agents in the line of transmission--has

been thoroughly debated, with visible and sometimes radical implications for

our editorial and interpretative practices. But when it comes to punctuation, editors

are now given minimal guidance and total power, while readers and viewers, for

their part, are almost entirely unaware of the silent performances that have

profoundly shaped the Shakespeare they see and hear.

- Having edited plays by Shakespeare, Jonson and

Marlowe for both the mass market and a more restricted academic readership, I

have been required in every case to repunctuate, mostly silently and generally

in conformity with modern conventions. Like Cobden-Sanderson, I initially found

the process of updating the pointing in the early printings of these texts

liberating and satisfying, delivering the clarity and speed that effective

modern punctuation is capable of providing. But the more editing I do, the more

unsettling I find the license I have been given and the liberties I have taken

with it, and the closer I come to the position articulated by Theodor Adorno in

his brilliant little essay on punctuation marks:

The writer is in a permanent predicament when it comes to punctuation marks; if one were fully aware while writing, one would sense the impossibility of ever using a mark of punctuation correctly and would give up writing altogether. …The writer cannot trust in the rules, which are often rigid and crude; nor can he ignore them without indulging in a kind of eccentricity…. The conflict must be endured each time, and one needs either a lot of strength or a lot of stupidity not to lose heart (305).

What Adorno says of writing applies--with less irony--to editing. As those of us who have been strong or stupid enough to take it on can testify, the conflict must be endured not just each time we edit but each time we encounter a punctuation mark--particularly when they appear where we think they shouldn't, when they don't appear where we think they should, or (worst of all) when they appear in a form for which there is no obvious modern equivalent. In fact, it may not be going too far to suggest that every piece of punctuation poses something of a textual crux.

- In the face of this struggle, Cobden-Sanderson was

by no means the only twentieth-century editor to have misgivings about

modernization. When Martin Seymour-Smith edited the Sonnets in 1963, he

welcomed the widespread (if partial) reversal of the modernizing trend, first

established by Edmond Malone in his edition of 1780: "The tendency of the

present century, beginning with George Wyndham's edition of 1898, has been to

return more closely to the original text--but not to the original

punctuation" (8). He chose to preserve not only the spelling but also the

punctuation because

Shakespeare's punctuation looks and feels right in its proper context [and] looks, feels and is wrong when applied to a modern standardized text. ...in order to punctuate according to modern rules, an editor is often forced to make up his mind about the meaning of the original. This means that the sense of the poem is narrowed down; it is often robbed of a multiplicity of meaning which may be an inherent part of it. Secondly, the rhythm is interfered with. Thirdly, it is plain that violence will be done to the complex structure... (37-38).

When John Dover Wilson edited the Sonnets for the Cambridge Shakespeare three years later, he followed a similar policy: "to impose a modern punctuation upon the Sonnets would indubitably lead to misrepresentation. The only safe thing then, the only scholarly thing, to do is to leave the Q text virtually unchanged in this respect" (cxxiv). But when the Oxford Shakespeare finally appeared (in both old- and modern-spelling editions) in 1986, its editors were far more comfortable with modernization: indeed, they had literally written the book on updating Shakespeare's spelling for modern readers (Wells and Taylor; Wells). And over the last few decades, it is safe to say, silent repunctuation has become the order of the day for poems and plays alike.

- Editors are traditionally forced to justify

departures from their early modern copy texts, and they are supposed to have a

good reason if they change some feature in the most authoritative early text.

But this burden is largely lifted when it comes to punctuation. How did this

position come to win out and on which arguments and/or assumptions does it

rest?

- There are at least four major positions in recent

thinking about punctuation that have led editors to edit out Elizabethan

phenomena such as the serial colon, and that have served (more generally) to

deflect attention from the pointing preserved in early printings of

Shakespeare's plays and poems:

1. Punctuation plays at best a secondary role in the production of meaning: it is the words, rather than the marks between them, that count. This widespread (but usually tacit) assumption lies at the heart of modern editorial theory and practice and derives in part from W. W. Greg's influential division of texts into "substantives" and "accidentals." He put punctuation in the latter category alongside spelling and layout, describing them as surface features that shape and inflect but do not usually create or contain the verbal meaning found in the so-called substantives--that is, the words themselves. The net effect of Greg's argument was to set in editorial stone the already prevalent tendency to see punctuation as an adjunct to rather than component of meaning: Vivian Salmon has explained that the term "accidental," as it became hardened in editorial ideology, implies that the marks between words are contingent rather than constitutive, the product of happenstance rather than control. The Latin etymology suggests that they simply fall onto the page and might just as well have fallen elsewhere; and the relevant entry for "accidental" in the Oxford English Dictionary defines them (citing Greg) as "any feature that is non-essential to the author's meaning."

For some scholars, such multiplicity and uncertainty completely undermines the value of early accidentals as potential evidence for authentic preferences of any sort; but at the very least, it calls into question the naive devotion of earlier editors and critics toward the "original" punctuation, which may well be compositorial or scribal rather than authorial. In his groundbreaking study of compositors and punctuation in Eld's 1609 Sonnets, MacD. P. Jackson takes William Empson to task for such bibliographical naivety:

2. Sixteenth-century practice was so primitive and inconsistent as to be almost useless to modern readers. Everyone who writes about punctuation in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries spends some time explaining two things. First, that until the sixteenth century there were only four punctuation marks in general use (comma, colon, period, and question mark), and that the great European printers introduced new ones that were adopted by writers in a slow and irregular fashion over the ensuing centuries (Parkes 41-61). And second, that these marks served two different systems that were both in play during Shakespeare's day. We now see the function of punctuation as primarily grammatical, intended to guide us through the structure of a sentence by clarifying the relationship between the separate syntactic units within it. But in the Renaissance there was a second (and, to some extent, dominant) approach that can be described as rhetorical or oratorical, indicating pauses for breath and changes of pitch--a form of marking that becomes increasingly obsolete, or at least subordinate, as we move toward the present (Parkes; Ong; Salmon; Graham-White).

3. Early modern punctuation is too difficult or confusing for modern readers to handle: it must therefore be translated into a form that they can understand--and can, indeed, be done so without losing anything essential to the original effects. Fredson Bowers was as committed as anyone to the recovery of texts as their authors would have wanted them to appear, and he regularly argued for the retention of original spelling and pointing. But if editors decide to modernize, he had little patience for halfway measures and suggested, for instance, that "it is absurd to argue that Elizabethan flexibility and rapidity cannot be indicated by especially light modern pointing" (138-39).

4. The transmission of Shakespeare's texts has involved so many intermediaries that the hope of recovering Shakespeare's own habits is all but futile. According to the useful summary of Peter Stallybrass and Roger Chartier,scripts required collaboration--of the professional actor to phrase the words and, if printed, of the compositor to "point" them. The instability of the text, while increasingly emphasized by modern theatrical and editorial practices, is the material result of the multiple agents in the theaters and printing houses, all readers of the text, in the making of the performances and books through which spectators and readers encountered specific versions of the script/text. There is no single 'original' text that we can find behind the various materializations of Hamlet (37).William Empson quotes the first five lines of Sonnet 32 as illustrating "one of those important and frequent subtleties of punctuation...":

If thou suruiue my well contented daie,

He remarks that "Line 4 is isolated between colons, carries the whole weight of the pathos, and is a pivot round which the rest of the Sonnet turns." Empson's comments on this and other sonnets are stimulating, but it is worth pointing out that line 4 is "isolated between colons" because the page on which it appears was set by Compositor A [who had a marked preference for colons] (8).

When that churle death my bones with dust shall couer

And shalt by fortune once more re-suruay:

These poore rude lines of thy deceased Louer:

Compare them with the bett'ring of the time, - Likewise, T. H. Howard-Hill has warned us against attributing

the clusters of colons found in some of the First Folio plays to Shakespeare

himself since they were prepared for the printer by the scribe Ralph Crane and

the frequency of colons found in his texts is roughly twice that found in the

rest of the volume (32, 82).

- Similar uses of the serial colon can be found,

however, in plays that were not prepared by Crane and patterns like the one

identified by Empson cannot be simply pinned on the carelessness or quirkiness

of a particular compositor. First and foremost, they point to patterns that

were produced at the time of Shakespeare and even if they are not Shakespearean

they may point to structures or effects that were familiar to his earliest

readers (Carter 427-28). And second, it is by no means clear who is responsible

for the patterns found in the 1609 pointing: serial colons are found in no

fewer than 32 other sonnets, only half of which were set (according to

Jackson's own assignments) by Eld's Compositor A, and these help to sustain no

fewer than ten sonnets that stretch out, in the Quarto's punctuation, over a

single sentence, all but one of which were set by Compositor B.[8] There are elaborate examples of

serial colons throughout the plays in Shakespeare's First Folio, particularly

in speeches associated with clowning and soliloquizing, suggesting that a

string of colons may have signaled a particular set of speech-acts or -genres

in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (associated, I would suggest, with

the turning of phrases, the unfolding of ideas, the weighing of options, or the

finding of one's way). So in scripting "a speaker who seems to think his

way to his conclusions before our very eyes," as Vendler described the

effect of Shakespeare's sonnets, the serial colon may have been the pointing of

choice (Shakespeare, The Sonnets, ed. Vendler n.p.).

- It is clear, at any rate, that the colon fulfilled

a number of functions. In both the logical and the rhetorical system deployed

by Shakespeare's contemporaries, colons mark a pause that is longer than a

colon but shorter than a full-stop, and they also indicate a part of a larger sentence

that is not yet complete. In Charles Butler's English Grammar of 1633,

the colon is described as "a point of perfect sens[e], but not of perfect

sentenc[e]" (sig. H1v). This formulation may derive from Quintilian's

Institutio Oratoria, the Renaissance period's most influential classical

handbook on the art of rhetoric. In the section on punctuation in Book 9,

Chapter 4, Quintilian explains that the colon is "the expression of a

thought which is rhythmically complete, but is meaningless if detached from the

whole body of the sentence, as the hand, foot or head if separated from the

body" (3:577). In early Greek and Latin usage, the colon refers not to the

punctuation mark but rather to the clause (or, literally, member) which

it accompanies; and since rhetorically effective sentences often need multiple

clauses before they bring their sense to an end, classical authorities accepted

that there could be many cola in a sentence. Quintilian says that Cicero

advocates an average of four, and finds them especially useful when we want to

"relax the texture of our periods by considerable pauses and looser

connexions" (3:579).

- This description points us toward a fundamentally different

understanding of the nature and function of sentences and the use of colons

within them, one poised between written and spoken speech and capable of a

length and complexity that we are no longer trained to tolerate. When

Quintilian's guidance was revived by Renaissance humanists, they inherited his

toleration for multiple colons--not just clauses, that is, but actual marks of

punctuation. For English readers, the most explicit statement along these lines

was found in the chapter on "distinction or pointing" in John Hart's

1551 treatise, The opening of the unreasonable writing of our Inglish Toung.

He begins with the comma (which he compares to the crotchet in music) before

moving on to the mark

the Grekes cal colon...which is in inglish the iointes, or that which is betuixt the iointes...for that yt devideth the membres of a sentence, as our ioints doo the membres of our bodies: whose quantitie is dooble, of that of the foresaid rest, which we may compare to the minem yn music.... The same membre may containe 1. 2. 3. or more of the said restes: and his use is; as you see in everi periode...in this boke written: that is to sundre...membres of sentences...as, I am veri glad of your prosperite: for I herd say you were in trouble: which now appeareth otherwise: and so of others (Danielsson I:159-60).

By the time Ben Jonson wrote not only his plays but his own textbook on English Grammar, he joined Aldus and Hart in combining the different functions of punctuation: in the organic body of the text, logical punctuation marks its skeletal structure and rhetorical punctuation marks its breath or music (Van den Berg; Smith; King). Faced with an author working with such a different understanding of language, Stephen Orgel suggested in his Yale edition of Jonson's Complete Masques, "no method of modernizing can be wholly satisfactory" since "Elizabethan syntax was vastly different from ours, and included devices for which there is no equivalent" (44). Like many other editors of early modern texts, he has tried to help his readers by lightening Jonson's heavy marking and clarifying his tangled syntax, but unlike most of them he does so with a full awareness of what is lost as well as gained in translation.

- When we modernize the punctuation in Renaissance plays or poems, we are not so much replacing one system with another as taking texts from a culture where two (or more) different systems are in open and often ambiguous play into a culture where one has won out. This problem led Orgel to acknowledge that "attempt[ing] to reduce Jonson's practice to ours is as impossible as it is misguided," and Michael Warren to argue that editors should be much more cautious in removing non-modern pointing and much more generous in telling readers what exactly is being removed. The serial colons in Shakespeare's sonnets are, I would suggest, a particularly interesting case in point.

Notes