Updating Folios: Readers’ Reconfigurations and Customisations of Shakespeare

Noriko Sumimoto

Meisei

University

sumimoto@eleal.meisei-u.ac.jp

- Readers’ annotations

and other marginalia seem to have established themselves as an important

field of interdisciplinary studies

of readership. In A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology, Peter Beal recently wrote that the “Marginalia, made

by readers of books from medieval times onwards,” which include, amongst other

things, “glosses, side-notes, markings

. . . , corrections of errata or textual emendations

. . . or else brief or detailed comments

on the text itself . . . can throw . . . great light on the responses of

contemporary or early readers and on their

engagement with the texts, providing

valuable sources for the history of readership” (247). Following up on Beal’s

comment, this essay will focus specifically on what William H. Sherman has

called the “customisation” of books (Used Books 36), a term he uses to

describe the way that books were altered “according to [readers’] needs and

tastes” (36). The concept

of “customizing books” by readers offers us a way to interpret “the

mysterious marks that get left behind” (Sherman, Used Books xi)[1]

by unknown readers in the manuscript marginalia

of some of the surviving

copies

of the four Shakespearean Folios.

- When we started the Meisei University Shakespeare

Collection Database with the richly

annotated First Folio copy (MR 774; West 201), we had hoped that eventually

all the folios in our website would

contain at least some manuscript

annotations.[2]

The Third Folio copy shelfmarked MR 733 especially made us feel fortunate, since it is annotated throughout the volume except for the apocryphal pages. Yet, at the same time, the copy

puzzled us as to how to make sense of

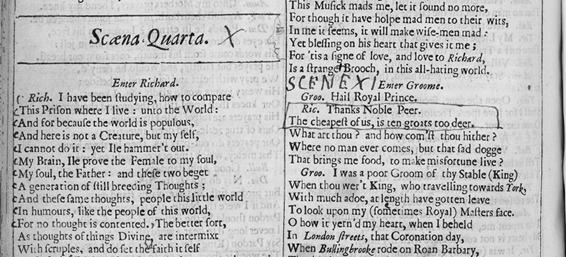

the meticulous ink strokes that frequently fill the copy’s lower or sometimes outer margins as well, as, for example, on Ttt1r (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1 MR733, Ttt1r Meisei University Library - It

was soon to be discovered that its annotator transferred onto the copy the

footnotes of Sir Thomas Hanmer’s edition.[3] Nevertheless,

a couple of questions remained. Why did the annotator do that? And was this

person the only one ever to have annotated Folio copies in such a manner? By comparing the “customisation” of

this copy with that of other Shakespeare Folios with manuscript marginalia, I

was able to begin to answer both of these questions.

- To date we know of two scholars who were

once similarly bewildered facing, in

their own folio copies, numerous manuscript additions that each seemed to do

very little more than reproduce the editorial contributions of a single, eighteenth-century

edition.[4] One is John

Fitchett Marsh, who, reading a Third Folio copy now housed in the Folger

Shakespeare Libary and shelfmarked S2914 Fo. 3. No. 2, noticed that the annotations were almost identical with those found in Alexander

Pope’s edition. This led him initially

to believe that the copy was once owned and annotated by Pope himself, but when the graphology revealed that

the annotations were not penned by Pope, Marsh was so puzzled that he wrote

that it was “difficult to imagine an adequate motive for taking the trouble of” copying Pope’s annotations (199).

- Bodleian Arch. Gc. 9, a Second Folio copy

bound together with the Fourth Folio’s

apocryphal pages, appeared similarly to puzzle Mary Bradford Whiting. In a signed memorandum,

dated January 1889 and now pasted on the copy’s

free endpaper, she observed that the

notes and stage directions were

derived from Nicholas Rowe’s

edition.

- MR733, Folger Third Folio

copy 20 and Bodleian Arch. Gc. 9 each bear witness of their respective annotator’s extended and sustained efforts

to carry out page-to-page collation,

covering over 900 folio pages with annotations from, respectively, Sir Thomas

Hanmer’s, Alexander Pope’s, and Nicholas Rowe’s editions of Shakespeare’s

plays.[5]

By investigating how the readers-annotators of each of these folios

followed or diverged from the scholarly editions to which they appeared to

refer, we might begin to understand how they customised their folios, and how

these customisations reconfigured Shakespeare.

Bodleian Second/Fourth Folio: Arch. Gc. 9

- By far, the majority of manuscript additions and annotations

left in the Bodleian Arch. Gc. 9 folio copy can be identified as having been

derived from Nicholas Rowe’s edition.

Among the innovations which Rowe’s edition had brought to the experience

of reading Shakespeare in 1709 were a critical biography of the author, plates

that illustrated a scene and

served as frontispieces to each play, character lists, more complete stage

directions, and more systematic scene

designations. John Prater, the apparent owner of this copy whose signature

appears on the title page (with the date 1698) and elsewhere in the folio (with

the date 1700), seems to have considered almost all of Rowe’s additions to be

worth transcribing as a way, as Whiting puts it, to “improve” his folio copy.[6]

- Prater was an attentive and voracious reader of Rowe’s famous

“Some

Account of the Life, etc. Of Mr. William

Shakespeare.” He not only created

a short version of Shakespeare’s

life out of the account and wrote it

under the list of “Names of the Principal Actors” (Sig. *), but

also inscribed various pieces of information it offered him wherever he thought fit throughout the copy. About The Merchant

of Venice, Rowe writes, “. .

.tho’ we have seen that Play [i.e. MV] Receiv’d and Acted as a Comedy, and the Part of the Jew perform’d by an Excellent Comedian, yet I cannot but think it was design’d Tragically by the Author. . . .The Play it self, take it all

together, seems to me to be one of the most finish’d of any of Shakespear’s” (“Some Account,” xix-xx). Prater took notice of these lines

and wrote “this Row Says is one of ye most

finisht of all his [.] he says it was he beleevs designd a Tragidy”

in the upper margin of the first page of the play (O4r). His “much ye Same tale as Sophocles

Electra”on Hamlet’s

first page (pp2v) can be ascribed to Rowe’s “Hamlet is founded on much the same Tale with the Electra of Sophocles” (xxxi). Even a terse

inscription of “Q:Elizabeth” beside “a fair Vestall,

throned by the West” in A Midsummer

Night’s Dream (N3r)

looks like his homage to Rowe’s enlightening information. As Whiting notes in her memorandum,

even the inscription in the outer margin of the first page of Much Ado about Nothing, that “Benedict

&Beat[rice] have much

wit,” (N3r) can be

found in Rowe’s account.

- Prater even describes the picture plates that Rowe had

attached to each of several of Shakespeare’s plays in a delightfully unique

way. “Picture is” is Prater’s opening

formula

for the ekphrasis. That of Romeo and Juliet, for example, runs thus:

Picture is│Romeo & Paris│lying dead Juliet│kneeling by: a dager│she holds at her │breast a great │torch burning│sevral coming│with halberts│& a torch at a│distance (ii5v).

- Indeed Prater redesigned the final page

of each play by filling it with information he found on the first page of each play of Rowe’s edition—namely the character list and the scene information together with the plate. Rowe’s character list and the scene location are transcribed

into the space almost verbatim for most of

the plays, although plays like Macbeth

have different renditions, as

will be mentioned later.

- Rowe’s act and

scene designations are precisely followed, with very few exceptions. In fact,

so far as I can surmise from my analysis of digitized page images of twelve of

the plays, there are only two exceptions to this pattern: Romeo and Juliet 1.2

and The Merchant of Venice 2.2. Moreover, Prater not only marks Rowe’s

act and scene designations wherever they

are lacking in the folio text: he

also modifies the folio’s designations

to conform to Rowe’s. In addition, Prater usually, but not always,

transcribes Rowe’s indicators of location.

- While Prater seldom shows

interest in textual emendations at

word level, he seems to have valued Rowe’s stage directions, including the entrances and exits which Rowe

enlarged. While he does not reproduce all of Rowe’s directions, he does

transcribe the majority of them, with the notable exception of the Ghost

“spreading his arms” and “cock crows”

in Hamlet Act 1, Scene 1 and “To

Juliet” and “Kissing her” in the sonnet sequence of Romeo and Juliet. Almost all Prater’s stage directions are derived from Rowe either

verbatim or in paraphrases.

- However, not all of Prater’s annotations can be attributed to

Rowe’s influence, for quite a few of his entries reflect his

interest in his contemporary Shakespearean stage, including titles of contemporary adaptations

such

as Faerie Queen and Bottom the Weaver and

The Injured Princess or the Fatal

Wager in the title pages of the

relevant plays. His

annotations also include, in

some cases with the date and venue of performance,

actors’ names, probably drawn from

the printed texts or some contemporary performance documents, if not from the memory of attendance at the theatres in person. For example, Prater refers to a performance of Macbeth at Haymarket

on 29 December 1707 in a cast list

that he prepares on a different sheet of paper and then attaches to the centre

of the finis box (pp2r). The listed cast, starting with Betterton

playing the part of Macbeth, is identical

with that recorded by The

London Stage, which lists a Macbeth

performance for that date at the

Queen’s Theatre

(Part 2 1700-1729,

162).

- Moreover, the annotator often refers to

“Shadwell” or “the new” in his pen

and ink additions to the text of Macbeth,

as if he is trying to update his folio text by

recording what alterations were made

in the contemporary version of

the play. His annotations are justified if you compare them with

Davenant’s Macbeth first

published in 1674. He enters parentheses in the side margins to show the passage

omitted in Davenant’s play

(oo5r), and makes

brief notes about the new lines and scenes added as in oo2v: “ad 60 lines bet: Macduff & Wife in Shadw.” He is rather

careful about the characters

omitted or replaced in the adaptation

and revises the Folio entrance and exit

stage directions accordingly (nn4r). He also adds the new stage directions he finds useful to enhance the imaginary understanding of the play in performance, as in nn5r: “Macbeth going out Stops & speaks whilst ye K: talks

wth Banqo

in Shadwell.” The annotator seems erroneously to attribute the Macbeth

adaptation to Shadwell (although he accurately attributes the Timon of

Athens adaptation to him).

Folger Third Folio copy 20: S2914 Fo.3 no.20

- The present state of Folger Third Folio copy 20 reveals the repair

work that the copy has undergone. It

is rather heavily damaged at the tail

throughout, so that many leaves are repaired with a reinforcing strip,

and the text that has been mutilated is written on a piece of paper interleaved where appropriate. These

interleaves are written in the same

hand as that of the marginalia of the main text, and both appear almost

exclusively to be either transcribed or to refer to the edition by Alexander Pope first published in 1725.

- Although John Fitchett Marsh was silent about them in his N&Q article, there are

three entries in which the annotator directly mentions

Pope in this copy. The three entries

are all about Pope’s rearrangement of

scene order as, for example, in Henry V: “This Chorus in Mr: Pope’s Edition is placed at the beginning of the 2d Act” (Ll4v).[7] Almost all the other manuscript additions

and annotations in this copy can be safely said to have been derived from Pope’s.

- Pope built his edition of Shakespeare’s plays in part by

amending Rowe’s: by adding source information

for 13 plays, systematic scene designations, footnotes, commas

for shining passages, and stars for beautiful scenes, and by degrading parts of the text

that Pope thought unworthy of Shakespeare to the bottom of the page. To all of these features the annotator of

Folger Third Folio copy 20 pays rather close attention.

- Whereas John Prater

added scene information

he found in Rowe into the final page of each play, the annotator of this copy chose to place scene information in the upper margins above head titles of each

play. Pope supplied no scene information

to The Second Part of Henry the Fourth,

and the annotator followed suit. In

addition, Pope’s scene designations

are fairly faithfully introduced

throughout the copy. The annotator reproduces Pope even where Pope gives erroneous numerals in

Lear Act II, where

Scene VI is given to two consecutive scenes. As

for the location indicators usually accompanying

scene designations, the annotator follows

Pope a little half-heartedly. Although the Folio text space is often

forbiddingly tight to allow an easy practice of this sort,

even where ample space is available, location

indicators are

sometimes just ignored.

- Pope famously wanted the lower margin of his edition to be the space where his

editorial duty discharged

should “show itself” to the readers. Thus, he puts “various

Readings” in the lower margin in footnote

form (vol.1, xxii). The annotator, apparently comparing Pope’s

emendations with the Third Folio’s readings, usually, although not universally,

records Pope’s emendations in the Folio margins when they are different.

Occasionally, he also employs Pope’s silent emendations to create an original

footnote.

- Pope also explicates, in footnotes of various length, “The more

obsolete or unusual

words” (ibid.). The annotator seems to have been able to

cope with many of Pope’s short notes, but lengthy ones must have posed difficulty

in transcribing onto a copy with

such severely shaved margins. Sometimes

the annotator deals with the scarcity

of

space by summarising Pope’s

note, or just stopping in the middle of a transcription

thereof.

- Finally, Pope evaluates passages of the play. For example, he

explains that “some suspected passages which are excessively

bad, . . . are degraded to the bottom of the page; with an Asterisk referring

to the places of their

insertion” (ibid.), and he places

triple daggers at the heads of scenes he found too gross in taste. Pope also

marks his approbation of certain passages and scenes: he writes, “some of the most

shining passages are distinguish’d

by comma’s in the margin; and where the beauty lay not in particulars but in the whole,

a star is prefix’d to the scene” (xxiii).

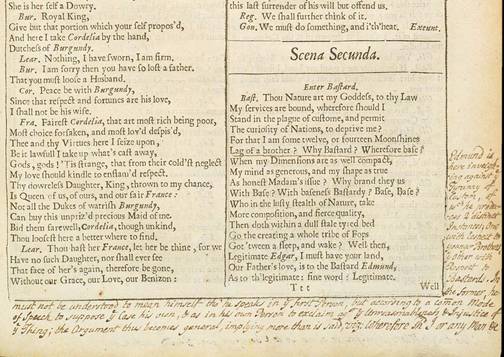

The annotator, apparently in agreement with Pope’s

evaluations, places boxes around those passages which Pope deemed to be

“excessively bad,” as seen in Figure 2. He also reproduced almost all of Pope’s commendatory marks,

using inverted commas and asterisks. Remarkably, the annotator not

only copies these marks from Pope but also contributes his own, using

double commas to signal his own

commendation of passages and asterisks to mark his favouring of specific scenes.[8] He even

draws the profile of a face looking at the words “Scaena Quarta. X,” which

introduce the scene in which King Richard the second is killed in the prison cell (Ff4v), most probably as a token of admiration

(see fig. 2).[9] Thus, the annotator seems to have judged the scene rather

enthusiastically.

- In addition to supplementing Pope’s evaluations of the play

with his own, the annotator appears to have consulted other sources. For

example, while the source information supplied by Pope is transcribed

diligently for twelve of the thirteen plays, the annotator

does not seem to have been sufficiently impressed by Pope’s observation that “This Story

was not invented by our Author; tho' from whence he took it, I know not” (vol.

6, 344). Instead, in a speculation probably derived from the edition by

Theobald (vol. 7, 226), the annotator wrote, “This

Story is taken from Saxo

Grammaticus in his Danish History.”[10]

- Meisei Third Folio,

copy shelfmarked MR733, is the second issue

published in 1664. On its title page is inscribed “John Millett Prescot,”

who must have been an owner of this copy at one time, but whether the manuscript annotations in this copy are also in his hand

is difficult to say.

- The annotator demonstrates a selective attitude toward the

various features of the Sir Thomas Hanmer edition. In his preface, Hanmer

says he has devoted his attention to

emending the text, to placing

spurious passages at the bottom of

the page (adding in the process a few sentences to the passages that Pope had

degraded to the bottom of the page of his edition), to adding a glossary at the end of the edition, and to

supplying footnotes that clear up difficulties arising “from a reference to some antiquated customs now forgotten, or other causes of

that kind” (vol.1, v). For his or her

part, the annotator takes care to transcribe onto the recto pages of both the

front and rear flyleaves the glossary that Hanmer appended to his edition’s sixth volume. He or she also transcribed the explanatory footnotes, but

appears to have opted not to follow Hanmer’s practice of degrading passages of the text. As for

other editorial features, the

annotator transcribed all but

one explanation of source information that Hanmer supplied for 13 plays, and only one of the character lists that Hanmer

appended to all of the plays.[11]

Although the annotator

does sometimes pick up scene designations, location indicators, stage

directions, and textual emendations, they

are quite clearly not his or her chief concern.[12]

- There are about 430

footnotes in Hanmer’s

Shakespeare, 65 percent of which are those aimed

at explanations, while the rest are

for recording those portions of the text

that he discards because they are “spurious.”

The annotator copied more than 85 percent of Hanmer’s explanatory notes into his or her own

copy of the Third Folio. In 21 out

of the Folio’s 36 plays, the annotator transcribed all

of them. As in King Lear (Ttt1r) [see

fig.1], nearly 80 percent

of the entries the annotator brought

to the copy are transcribed very carefully and almost

verbatim, if we admit certain accidentals such as the use of capitalization, punctuations and

various forms of contractions. For

the remaining 20 percent of the

notes, the annotator edited them into shorter forms chiefly for the purpose

of saving space.

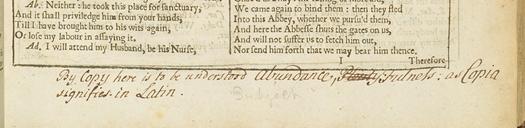

- Reproducing Hanmer’s notes verbatim wherever possible must have been the annotator’s preferred method, as the surviving errors seem to indicate. Only four errors can be found throughout the copy, an example

of which is shown in figure 3. Here the annotator had erroneously inscribed “Plenty” for Hanmer’s

“fullness,” an error which he corrected by crossing it out.

- Had it not have been for the annotator’s

interest in copying Hanmer’s notes faithfully, these errors might have seemed

by no means serious enough to be crossed out, for these

corrections risk marring the text’s elegance, about which the annotator seems

to have been also very particular.

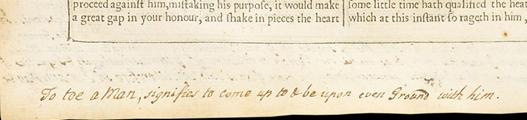

- In

fact, his or her careful treatment of show-through clearly indicates the

annotator’s investment in producing an elegant text. As Akihiro Yamada repeatedly remarks

in transcribing the

marginalia left in West 201, show-through often made the annotations difficult

to read. Throughout MR 733, no case

is found where show-through from the recto page has made the

annotations on the verso difficult to read. The annotator successfully

avoids such difficulty, for example,

by shortening Hanmer’s

note in Lear TLN 355 (Ttt1v): where Hanmer’s notes reads “As the treading

upon another’s heels is an expression

used to signify the being not far behind him; so toe another

means to come up to and be upon even ground

with him,” the annotator’s is shortened to “To toe a Man, signifies to come up to & be upon

even Ground with him” (see fig. 4).

Fig. 4 MR733 Ttt1v. Meisei University Library.

- In one case, the annotator even prevents

show-through by transferring a note to another page. Hanmer’s note about the word “Nuthook,” which

the annotator should have inscribed

on D2 verso, is transferred to Ll1 recto, the sole alternative page

available in the Folio on which the same

word occurs, and unlike the D2 verso, free of show-through.

- And yet, the copy does not simply reproduce Hanmer’s

notations. While the copy includes 241 footnotes directly from Hanmer, it also

includes three which seem to have come from elsewhere. One of them is the case in Hamlet (Qqq4v), where the annotator added “Startling

means I should think sterling” as a note to the word “startling,” a

form peculiar to the Third Folio. The hand seems to me to be identical to the one above it on the page, but it may be a product of some second session of annotation. I think it possible to find in

the annotator’s employment of “I

should think”—the same phrase as

professional editors sometimes use in

their notes—a joyful feeling of the

annotator’s self-esteem.

- These three cases are not the

only cases of such Folio customisations.

Although Bodleian Gc. 9, so far as my

research has determined, is the only copy whose customisation is informed by

Rowe’s edition, Folger Third Folio copy 20 and Meisei MR 733 are

by no means the sole examples of Pope- or Hanmer-based customisations. For example,

some of the comedies in Folger Second Folio copy 22 are also annotated after

the edition of Pope. Hanmer’s

edition might have been used as a source for

another thorough-going folio customisation, namely Folger First

Folio copy 70 (West 128) which, as

far as I have been able to access to date, is the only copy among

the First Folios that has

similar types of annotations throughout.

- In one sense the particular

type of Folio customisation that the

eighteenth-century annotators of Shakespearean folios might be said to

demonstrate can safely be called “updating,” a process stimulated, perhaps, by

the successive publications of brand new editions of Shakespeare in the

eighteenth century. Yet the source of stimulation might be found earlier and elsewhere than in the printed pages of

newly edited Shakespeare. John Prater, if

we may regard him as the annotator of Bodleian Gc.9, seems to have begun somehow updating his Second/Fourth

Folio copy around 1700,

probably shortly after his acquisition of the copy.

He found his updating source in the contemporary Shakespeare, either in performance

or in printed material, including Restoration Quartos of

Shakespearean adaptations. In a

gracefully un-intruding way in the side margins, he recorded parts of the folio text

that were omitted or altered in the

“new” forms of Shakespeare. He also added some character lists, emendations, and helpful stage directions. We could not tell how long and how far he would continue his project of reconfiguring

Shakespeare by this method. However, what the remaining annotations in the copy indicate

is that once the brand new configuration of Shakespeare in the shape of Rowe’s edition appeared

in 1709, Prater found it both

valuable and convenient. This lead him to embrace it as the sole source for his

updating project.

- In the case of

Folger Third Folio copy 20, the

updating project was part of the work of repairing the physically-damaged Folio copy. The annotator seems to have found almost every configuration of Pope’s worth transcribing. He or she, nonetheless, must have been alert

enough to notice Theobald’s

criticism against Pope’s edition in Shakespeare Restored

or in his published edition. The

annotator borrowed from this second

source as well, though he or she did so only in very limited

instances. His or her strong preference for Pope’s annotations never wavered.

- The annotations left

in Meisei MR 733 reveal the annotator’s great concern for the physical elegance

of the final product, as if he or she were seeking to rival the elegant beauty of the first Oxford edition of

Shakespeare. More importantly, however,

the annotator seems to have been fascinated by Hanmer’s elucidation of the text, especially

the footnotes and glossary that clarified obscure words and phrases. Yet the annotator’s admiration

for Hanmer did not prevent him/her from enriching the text with personal emendations

and updates.

- I would like to conclude this short paper with a simple note of what the detailed analysis of the annotations have revealed to me about the three annotators: in using Rowe, Pope, and Hanmer to update their folios, these annotators are not following their single source blindly through and through. As we have seen above, they are ready to choose otherwise or diverge if need arises, a flexibility, I believe, only a great reader of Shakespeare, if not a scholarly reader, could possibly have.

|

|

Fig. 2 S2914 Fo.3 no.20, Ff4v. By Permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Meisei Third Folio: MR733

|

|

Fig.3 MR 733, I1r. Meisei University Library.

Notes