Extra-illustrating Shakespeare

Lori

Anne Ferrell

Claremont

Graduate University

lori.ferrell@cgu.edu

Sometimes the pictures for the page atone,

And the text is saved by beauties not its own. (Tredwell 11)

- To extra-illustrate, or “grangerize,” is to

add images to a book that, in its original state, lacks them. Or, better said, was

to add: a genteel, eccentric, and very popular post-Enlightenment leisured

pastime, grangerizing, and the persons who once were its avid practitioners,

have been nearly forgotten. Perhaps this is because what they did now seems so

very odd to twenty-first century tastes. These hobbyists (whose personal

letters, published lectures, and articles in nineteenth-century bibliophilic

periodicals chronicle their extraordinary passion for their avocation) cut

printed books out of their original bindings, inserted between those loosened

pages prints—and later, other artifacts—from their collections, and then

rebound and renamed them. In this way extra-illustration could transform a

mass-produced text into a one-of-a-kind, hand-crafted, luxury object. It was

based upon the premise that published books—those broadly-dispersed delivery

systems for an author’s words—could be refashioned into a connoisseur’s private

cabinet.

- Driven by a passion for collecting and

organizing rather than a desire to read and understand, extra-illustration

offers an intriguing take on the industrious, acquisitive, and sometimes

destructive obsessions of the Victorians.[1]

To an extra-illustrator, words served as registers of items, not as

signifiers of ideas. “Don’t allow yourself to read, or you will get

interested and surely omit entries you should make,” warned the author of “How

To Set About Extra-Illustrating a Book,” an essay in The Book Lover, an

American monthly aimed at bibliophiles (9). The admonition reminds us that a

love of books is not necessarily a love of reading.

- The idea that any page of Shakespeare would

require “atonement” of the sort described above (and in such bad doggerel

verse) might surprise and even dismay us. We would not be alone:

extra-illustration has been mostly overlooked by literary scholars, and the

relative few who have treated it tend to evaluate it using theories of

collecting or art history rather than of books, reading, or reception. But like

medieval manuscript illumination, extra-illustration could take on the

qualities of an interpretive art, and many an extra-illustrator put the purely

acquisitive and precisely technical aspects of the practice—the meticulous

cutting and pasting; the relentless collecting—to the task of paratextual

commentary.

- This achievement can be traced in the

extra-illustrated Shakespeares of the period, which offer particularly fine

examples of textual commentary alongside the usual beauties of pictorial

enhancement. In this essay, I will give an overview of the history and practice

of grangerizing, pointing out that its complex reading, binding, and

visualization practices were interpretive strategies. I will go on to

demonstrate this claim by considering the extra-illustration of two Shakespeare

sets dating from the mid nineteenth and turn of the twentieth century—the

period that witnessed, interestingly, the waning and end of the practice

altogether. Singular they may be, but the Huntington Library’s 1850s “Adlard

Shakespeare” and the Scripps College Denison Library’s 1901 “Henley

Shakespeare” nonetheless shed light on Shakespeare reception and performance in

post-revolutionary England and America.

Extra-illustration: an overview[2]

- Extra-illustration

allowed fashionable people to showcase their private collections of print

portraiture. Starting with a book on a topic of interest, the hobbyist would

haunt print stalls and consult art dealers, collecting as many prints,

engravings, drawings, and paintings as might serve to illustrate it. In the

late eighteenth century, extra-illustration was called “grangerizing,” in

tribute to its first great public advocate, the Reverend James Granger, an

otherwise undistinguished English cleric who avidly collected printed

images—not of martyrs, theologians, or biblical patriarchs, but of monarchs and

statesmen. Like others in his circle (most notably, Horace Walpole), Granger

also liked to collect engravings of “characters,” those portraits, quite popular

in the eighteenth century, of nameless “types”: A London Flower-Seller; A

Poor Woman; An Aged Rabbi. Granger and his friends engaged in friendly,

lively epistolary competition and exchange, trading engravings and putting them

on private display.[3]

- Soon

Granger decided to organize their efforts by means of an innovative device: an un-illustrated

book, one that would be equipped with lists of prints and blank pages for

notation. In 1769, Thomas Davies published Granger’s The Biographical History

of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution…Adapted to a Methodological

Catalogue of Engraved British Heads. An exhaustive catalogue that ran to

four volumes, the Biographical History was little more than a list of

extant portrait engravings. Attached under each of these “heads” were succinct

biographies made up of little more than anecdotes and character analyses:

sketches of another sort. Early purchasers of Granger’s Biographical History

were meant to use the catalogue as mere check-list, but more ambitious

grangerizers soon began pasting portraits directly onto its blank pages and,

after that, inserting them between its excised and rebound pages.

- Like all hobbies, collecting walks a thin

line between gentle pastime and fierce obsession. The quest could become

all-consuming all too quickly, and all too often. It soon captivated the

leisured classes of America. In a talk given to the Rembrandt Club of Brooklyn,

a late nineteenth century enthusiast named Daniel Tredwell (whose bad verse

opened this essay) vividly described a typical grangerizer’s progress:

Suppose we are in possession of…a sketch of the life of Edward Everett. Before sending it to the binder it occurs to us that it would be interesting and enhance its value to have a faithful portrait of Edward Everett as a frontispiece – a testimonial of our regard for this accomplished gentleman and scholar…We are by this time becoming interested in the pursuit, and beginning to feel we are no longer amateurs…so we go on getting prints…developing unconsciously an enthusiasm for our work, until we have twenty-seven engraved portraits of Edward Everett, illustrating his life from the age of sixteen to sixty…we want them, and we buy them. (Tredwell 34-36) [4]

(Fame being both particular and fleeting, here we may pause to recall, possibly with some effort, that Mr. Everett was a senator from Massachusetts and President of Harvard University in the mid-nineteenth century.) Tredwell went on to explain that this personal run on Everett portraits would invariably inspire the illustrator to broaden his ambitions: he would go on to locate and purchase, not only pictures of the gentleman himself at every age, but also pictures of the gentleman’s birthplace, his family, his extended family, his library, and his circle of friends.

- Having proved himself in this part of the

venture a bona-fide expert in Everettiana, Tredwell’s imaginary grangerizer

would then turn to handicrafts, using a specially designed knife to trim the

illustrations and rice flour paste to affix the prints to single sheets of one,

uniform size. He would excise the pages of the original Life of Everett

from their original binding and paste them onto sheets in the same size.

(Depending on the overall size, engravings could also be inserted, with or

without folding, directly into this newly created book.) Finally, he was ready

to insert the prints at the appropriate places: where the original biographer

had mentioned Edward Everett, his home, his library, his friends or anything,

really, in passing (39).

- This

extraneous aspect of extra-illustration—the willingness of the grangerizer to

expand on even the most insignificant detail of a written text with visual

images—was the practice’s most characteristic (and infamous) feature. For this

expansion was, most spectacularly and substantially, physical: the worthy

Everett grew in height and girth, his one-book life now requiring multiple

volumes of visual depiction. And so, an unremarkable quarto was transmogrified

into something extraordinary, unique and very, very large. Such transformations

merited new designations in addition to shelf space; check the spines and you

find the extra-illustrator’s name has often taken pride of place over that of

the original’s author.

- The system Granger originally described as “reduction” (for

its capacity to sum up a life at a single glance) soon inspired—as the

popularity of the extra-illustration grew, and as we see in Tredwell’s

invocation of the amplified Everett above—a number of extravagant expansions:

of successive editions of the Biographical History; of the market for

engraved “heads” and “types”; and, eventually and inevitably, of the market

price of such engravings. Would-be grangerizers consequently began to look to

other venues for print acquisition, purchasing already-illustrated books for

the sole purpose of raiding them and excising their pictures, and adding these

pictures to their collections. The price of those books then also rose

accordingly. The literary genres deemed suited to extra-illustration also

expanded, and soon encompassed travel narratives and geographical studies of

foreign and domestic lands; religious works and sacred texts (especially the

Bible); natural sciences and natural histories; memoirs of the theatre (a brisk

trade in portraits that named not only the player but identified him or her

with a stage character was soon established in the London print stalls); and

literary works, including, of course, Shakespeare’s.

- Based as the practice of “extra illustration” was in the idea

that a book could be made over into a capacious and almost-infinitely

expandable vehicle for the acquisition, preservation, and storage of a large,

ever-increasing collection, it is perhaps unsurprising that the range of what could

be considered “extra-illustrated” also expanded. Given the roomy definition—adding

pictures to books—texts un-excised but illustrated in the margins with

watercolor or oils also began to manifest in library lists as

“extra-illustrated” volumes. By the middle of the nineteenth century, in fact,

it had become commonplace to extra-illustrate not only by such direct

illumination, or with engravings purchased from the print stall and pictures

excised from other, less fortunate tomes, but also with a variety of pasted-,

tipped-, or bound-in artifacts: ticket stubs, newspaper clippings, formal

invitations, manuscript letters, booksellers’ bills of sale, and photographs.

And so, in becoming spectacular receptacles for all manner of visual inventory,

these “illuminated palaces” (to quote the besotted Tredwell) (34) would seem to

have long lost their identity as books meant simply to be read. Captivated by

their unique beauties, and the wonders of late nineteenth century print

advertising, other collectors purchased already extra-illustrated volumes from

rare book sellers and private owners; twentieth century booksellers’ catalogs

testify to the brisk but fleeting nature of the trade.

- Now virtually unknown and un-consulted,

extra-illustrated books take up impressive amounts of space on the shelves of

most research and many private libraries, dusty testaments to the odd allure of

a passing book-fancy. They first catch our eye by the scale of their ambition.

Turning the outsized pages of a Biographical History, a Life of

Everett, or The Works of Shakespeare, we grasp at the outsized

desires of the past: to acquire a complete collection of engraved portraiture;

to excise, mount, and place engravings into pages with precision and

artfulness; to gild the printed page and rebind its exteriors and, in so doing,

make any book over into something personal, remarkable, and entirely,

audaciously unique. In this alone, grangerized works have much to teach us

about the era in which they thrived: an age wherein books, finally made cheap

and readily available by the wonders of mass production, were reconceived and

repurposed as the singularly luxurious tributes to wealthy owners they had once

been in the past.

- But extra-illustrated books also have much to teach us about

past practices of reading, interpretation, and reception and this is where we

owe a debt of gratitude to the grangerized works of William Shakespeare that

flourished in the nineteenth century. These works represent characteristic, if

individual, approaches to textual interpretation. Grangerizing was, after all,

an expansive and thus inherently exegetical act: one that located meaning in

the relation between words; the mental images those words inspired, the created

pictures that made those words manifest; and, in the case of the plays, the

physical artifacts that accompanied these texts’ life on stage.

Extra-illustrated Shakespeare

- By the end of the nineteenth century we can discern two

dominant styles of extra-illustrating Shakespeare: the manner advocated by

Granger and its offshoots, and a more eclectic, “scrapbook” style that fully

emerged in the nineteenth century and seems to have enjoyed more popularity in

America than in Britain. This latter, artifactual style is occasional in

nature, linking the plays to the material modes of specific contemporary

productions, adding ticket stubs, programmes, posters, and other memorabilia to

reprints of the plays or to the memoirs of actors like Phelps or Garrick or

Siddons. As records of the material conditions of Shakespeare playing in

England and America they are an invaluable, and remarkably underutilized,

archive.

- In the former style of grangerized Shakespeare, the “heads”

that grace the pages of the plays are rarely those of the playwright. However,

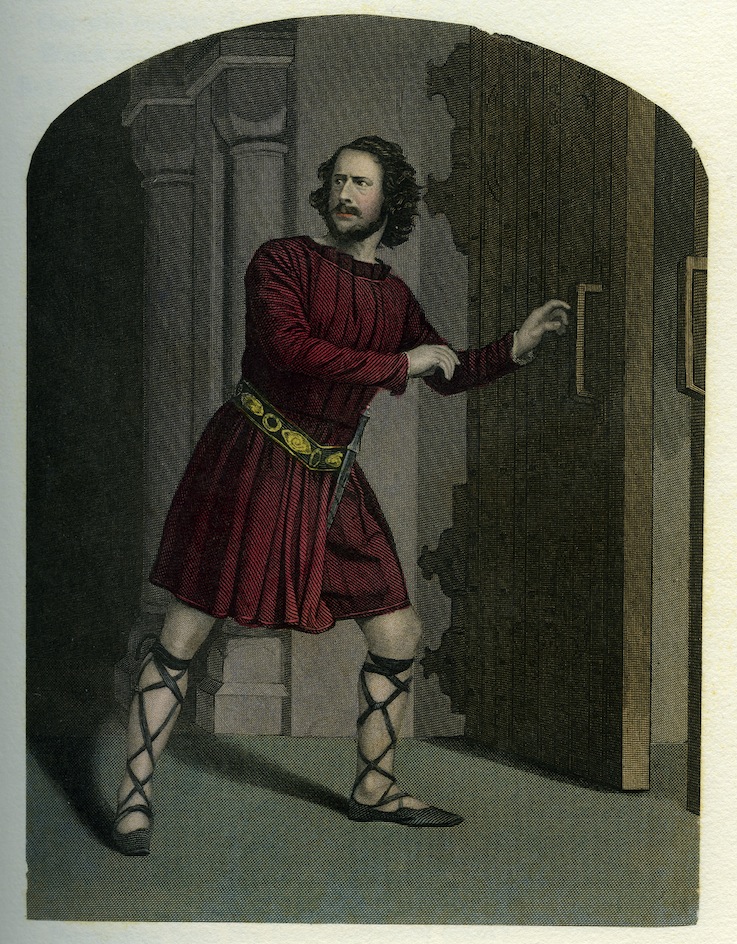

his characters, and the actors portraying these characters, reign supreme: Phelps

as Lear; Garrick as Hamlet; Mrs. Siddons as Lady Macbeth.

]

Figure 1: Samuel Phelps, famously, as Macbeth on the Sadler's Well stage of 1850. From the Denison Library of Scripps College's extra-illustrated Henley Shakespeare owned by Ellen Browning Scripps (1836-1932). By permission of the Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College.

- Here we find all that is irrevocable and enduring in the

literary version of the plays linked both to the occasion of an actor’s

undertaking of the role and to more general styles of theatrical

representation. Real people become “types” when rendered into engravings of

actors, monarchs, and statesman; their postures and facial expressions not only

show us how any character was likely to have looked on stage at the time; they also

suggest that these depictions, which endured reproduction and which were

readily available, might have lastingly influenced later portrayals.

- There are hundreds of extra-illustrated Shakespeares extant,

most of these dating from the nineteenth century and all of them worthy of new

study. But the extra-illustrated editions of Shakespeare housed in the

libraries established by two wealthy collectors who were both schooled in the

late Victorian age—Henry E. Huntington (who died in 1927 after founding the Huntington

Library in San Marino, California) and Ellen Browning Scripps (who died in 1932

after establishing a college for women in Claremont, California)—provide

particularly lovely examples of this characterized style of extra-illustration.

The

Ellen Browning Scripps Collection at the Denison Library at Scripps

College counts amongst its holdings a unique reworking of the “Henley

Shakespeare” of 1901-5. The original, a folio edition edited

by W. E. Henley, was published in Edinburgh and issued in

one thousand copies. The edition owned by Mrs. Scripps was already a special

one, limited to twenty-six lettered copies in what was called a “Connoisseurs’

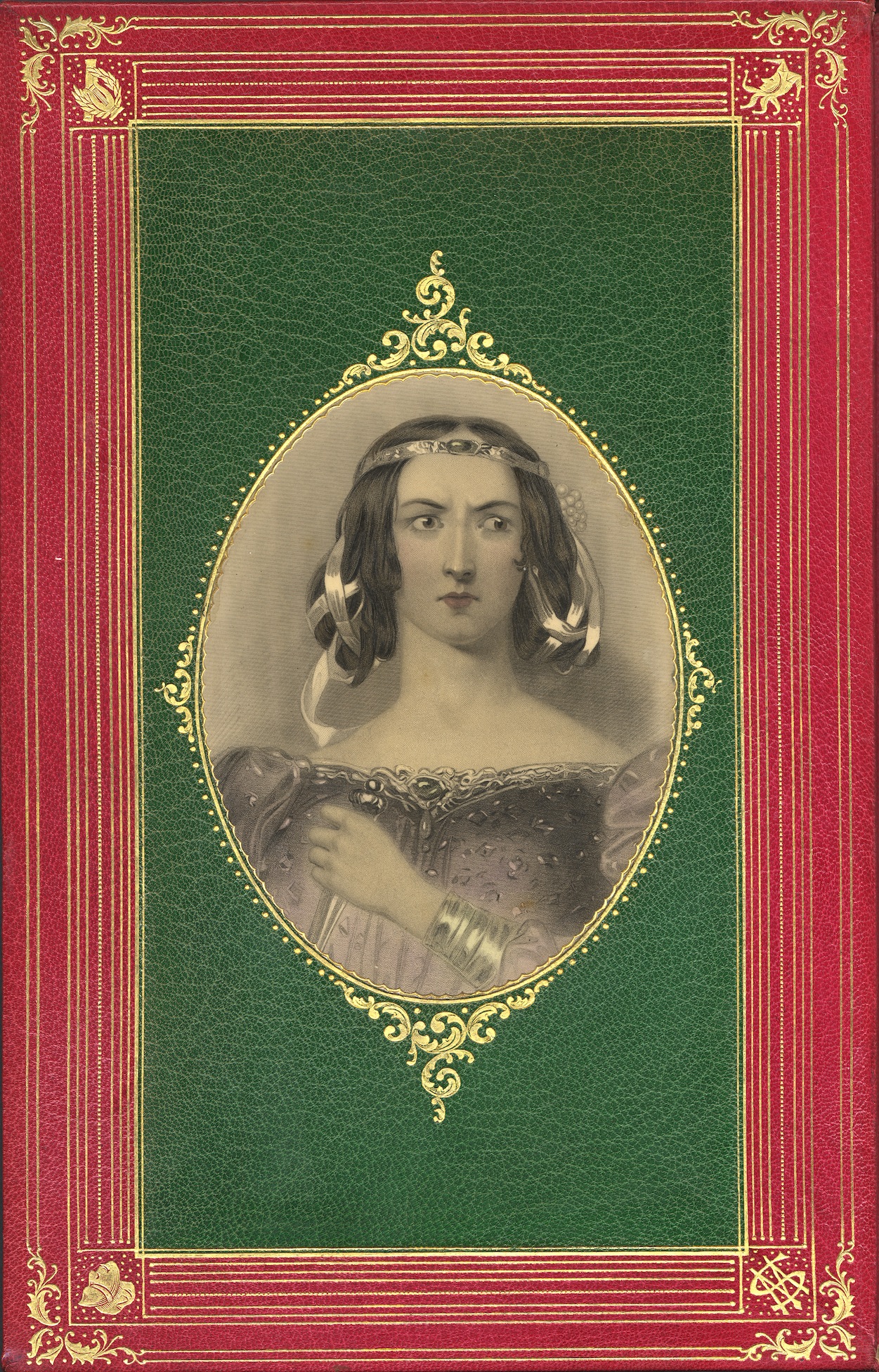

Edition.” The Scripps set builds on this with exuberant and professionally-crafted

grangerizing. The volumes feature a large number of fine inserted engravings, some of

them hand colored, as well as direct on-page extra-illustration, art nouveau in

style, in watercolor. Their bindings, red goatskin with green watered-silk

end-papers and leaves, have front and back covers inlaid with delicately tinted

portraits

of Shakespeare’s heroines in gilded roundels.[5]

]

Figure 2: The inside covers of Ellen Browning Scripps's "Henley Shakespeare" featured girlish depictions of Shakespearean women, not all of them heroines: this portrait depicts a young and beautiful Lady Macbeth. By permission of the Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College.

- What is particularly striking about this edition is in part

due to the late date of its extra-illustration: its added images represent the

latest versions of two centuries’ worth of reproduced characterizations and

stagings. The effect is one of uncanny familiarity: we recognize the faces and

postures and, if we are in a dreamy mood, marvel a bit whether Mr. Kean made

himself look so very much like Macbeth, or if instead Macbeth finally came to

resemble the long-dead Kean. The portraits thus implicitly make the argument

for Shakespeare as a playwright for the ages: they blur the lines between a

character’s representation on the written page and the conventions of that

character’s portrayal in the history of the stage, and animate those

conventions in a once-famous actor’s face and posture. Revisiting these

portraits, even as they appear in new, hand-tinted clothes, one feels as if,

say, the stage for the Macbeths’ crimes is always being reset: for tomorrow,

and tomorrow, and tomorrow.

- The Huntington Library’s sixteen-volume “Adlard Shakespeare”

(London: 1853-63) has a title so characteristic of the tireless and

encyclopedic interests of the Victorians that it is worth printing in its

entirety: The Works of William Shakespeare, the text formed from a collation

of the early editions: to which are added all the original novels and tales on

which the plays are founded; copious archeological annotations on each play; an

essay on the formation of the text; and a life of the poet by James O.

Halliwell. The illustrations and wood-engravings by Frederick William Fairchild.

The set is evidence of three characteristic passions of the age: for

archiving, for organizing and for copious supplementation. We might say that

this set, even in its original pristinity, owes its expansive nature and claims

to the influence of a century of extra-illustration.

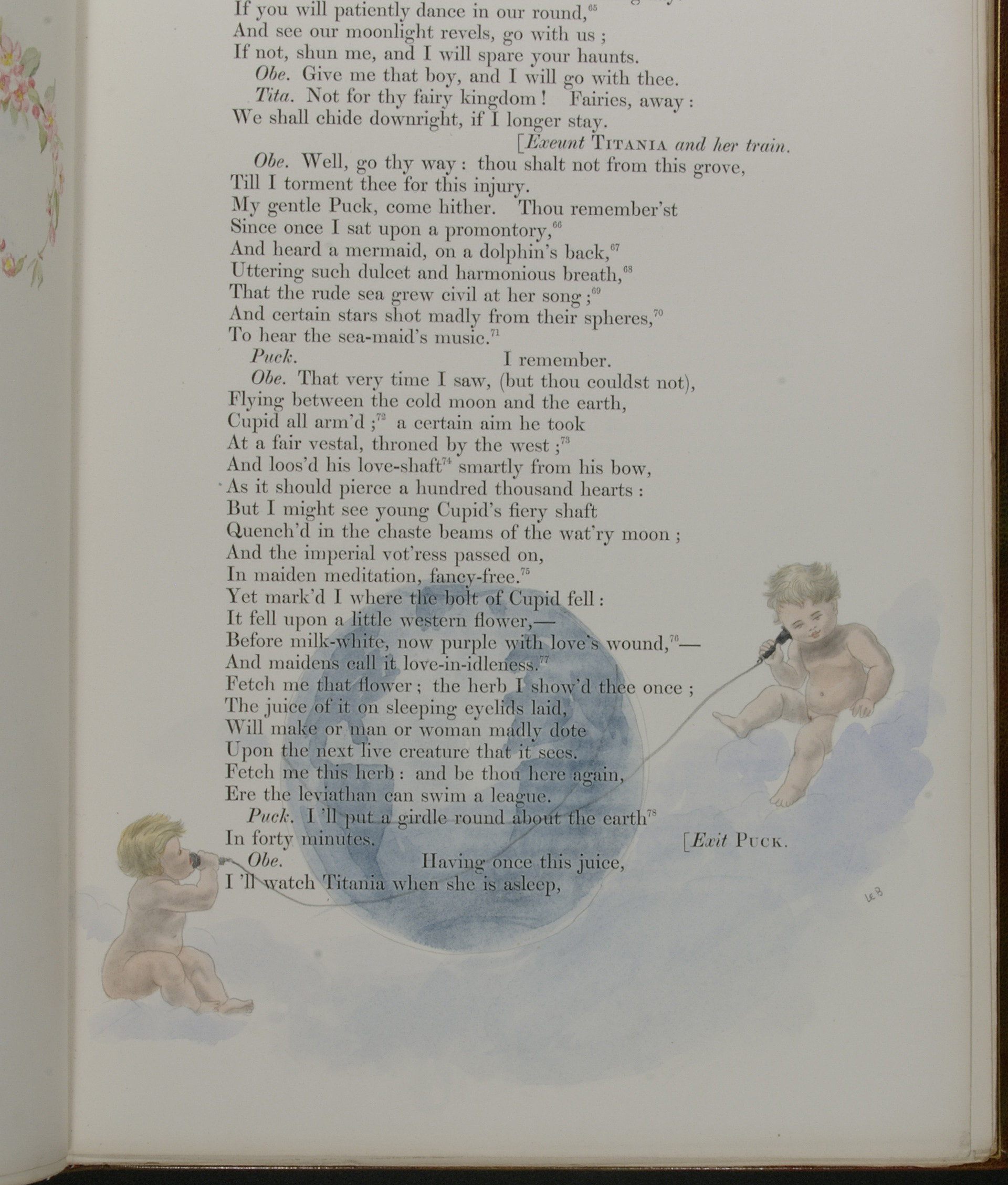

- But the hand-painted marginal illustrations are what make the

Huntington “Adlard Shakespeare” eligible to be catalogued as

“extra-illustrated”—and delightfully, thought-provokingly unique. For example,

a page from A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream sports a hand-painted Puck that

conforms to Victorian norms of childish charm: a chubby, naked cherub tumbling

toward earth in a red-peaked jester’s cap that makes him appear less powerful

than simply cute and charming (vol. 5, part 1: 61). But on the following page,

next to Puck’s boast that he will “put a girdle round the earth,” we find

Oberon’s tiny minion making a call on a new-fangled instrument known as the

telephone.

Figure 3: Puck girdles the earth in modern style in the Huntington Library's extra-illustrated Adlard Shakespeare. By permission of the Huntington Library.

- This is also charming in its seeming celebration of the

technological achievements of the nineteenth century; however and more

problematic, it yokes the image to Oberon’s magic. Placed against the text,

commenting on it, this image of Puck on the phone registers not simply a kind

of innocent wonder but also, perhaps, the anxiety that such power, in the end,

might have to be tamed and relinquished.

Conclusion

- By the late nineteenth century, the art of “illustrating a book with engravings torn out of other books” – was a pastime both in, and nearly past, its prime (“Methods of Illustration” 133). We see this beautifully demonstrated in two priceless library acquisitions of the early twentieth century: the Huntington’s “Adlard Shakespeare,” extra-illustrated sometime after 1860 and purchased by the Library in the 1920s, and Ellen Browning Scripps’s “Henley Shakespeare,” left to the Denison Library as a founder’s gift at her death in 1932. These are not simply collections of art and artifact related to Shakespeare, however. In them we discern nineteenth-century readings of Shakespeare that highlight and celebrate a sense of the author’s timelessness, his encyclopedic range, his prescience, his capacity to animate an otherwise generic humanity with singular character. In these sets, in other words, we find the Shakespeare of the Victorians. And with that, we might also concede, we have also found the source of the attitudes towards Shakespeare we still hear advocated today.

Notes