Mythological reconfigurations on the contemporary stage: Giving a New Voice to Philomela in Titus Andronicus

Agnès

Lafont

University

of Montpellier, France

agnes.lafont@univ-montp3.fr

- Critics have commonly acknowledged and regularly

studied the indebtedness of Titus Andronicus to classical literature and

mythology, especially its structuring of the Ovidian myth of Philomela.[1] Correspondingly, with the exception of

Trevor Nunn’s singular decision to cut all references to

Philomela in his 1972 RSC production, this classical reference is always

present in contemporary staging.[2]

- The

presence of this classical reference on the stage seems particularly apt, for,

as Leonard Barkan reminds us, in The Gods Made Flesh, Philomela “[...]

is not only a myth about communication: it is also a myth about the competition

amongst media of communication as Philomela becomes a walking representative of

them” (Barkan 245). In Lynn Enterline’s words, as she suffers “the unspeakable

act” of rape “[...] Philomela struggles at the limits of representation”

(Enterline 4). That is why, as Liz Oakley-Brown notes, she is seen as “[...] a

site for the violent interplay of various systems of signification and it is

these aspects of the myth which are explored and dramatised on the Renaissance

stage” (Oakley-Brown 26). This

article will address emblematic theatre in the sixteenth century through the

lense of its reconfiguration in two contemporary productions of

Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus: Yukio Ninagawa’s, in “The Complete Works

Festival,” Stratford-upon-Avon, 2006, and Lucy Bailey’s, at The Globe, London,

2006.

- How does one define emblematic theatre? Strategies

of theatrical representations and strategies of reading emblem books shared a

number of common features in the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries. Peter

Daly asserts that early modern drama was emblematic:

During the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries drama in its various forms was the most emblematic of all the literary arts, combining as it does a visual experience of character and gesture, silent tableau and active scene, with the verbal experience of the spoken and occasionally written word. (Daly 153)

Michael Bath took these remarks further by questioning what the choice of this emblematic frame of mind revealed about the English Renaissance episteme. His research on the corpus of Court masks or on the many rewritings of the Ovidian Metamorphoses led him to conclude that these reconfigurations of the Ovidian text could be read in two different ways: as a retractatio (or reworking) written by a successive tradition of different authors who each propose new interpretations of the myth, or as a series of repetitions that offer a crystallisation of a single meaning (be it physical, moral, allegorical or symbolical) of a particular fable. It seems to me that we ought to consider emblems in accordance with the former, less as a fixed repertory of pre-established readings (a ready-made compendium of classical wisdom in the form of common place books) and more like a repertory of variations on the myth, illustrating the adaptable quality of mythology.

- The history of printing of Renaissance illustrated

editions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and of mythological emblems derived

from Ovid, illustrate this point. Different images could be produced to

illustrate the same scene, as in Bernard Salomon’s illustration of the

abduction of Philomela in a 1557 edition of the Metamorphoses (Ovid,

La métamorphose d’Ovide Figurée n.p.) and Virgil Solis’s illustration of the same

scene in a 1563 edition of the same story, with the title “in Prognen” and an

added gloss (Spreng n.p.). On the other hand, because the Renaissance printer

had a stock of woodblocks that he would use to illustrate multiple texts, at a

lower cost than would be incurred if a new woodblock were created for each

text, the same illustration could also be used in very different contexts. For

instance, Bernard Salomon’s illustration was used both in

the 1557 La Métamorphose d’Ovide Figurée and in

Nicolas Reusner’s 1581 Emblemata (Book III, emblem 14).[3] It becomes apparent

that the so-to-speak emblematic meaning (in the sense that emblems are defined

as a type of normative literature) is submitted to various influences, very

specific to the mythological emblem and the conditions of printing. A common

repertory of mythological images is thus elaborated in different ways for, and

becomes familiar to, the early modern audience.

- Emblem

books of the sixteenth century, such as Barthélemy Aneau’s Picta poesis, ut

pictura poesis erit (Lyons: 1552) or Daniel Manasser’s Poesia Tacens,

Pictura Loquens (Dillingen: 1630), insist on the narrow relationship

between text and images. To write is to put under the eye, as Erasmus has it in

his De Copia (II). Defining energeia, he writes:

We do not explain a thing simply, but display it to be looked at as if it were expressed in colour in a picture, so that it may seem that we have painted, not narrated, and that the reader has seen, not read (De Copia qtd. in Daly 202).

Erasmus’s energeia is potentially realized by a rhetorical tool that is commonly used in the Renaissance: hypotyposis. This trope offers the possibility of bridging the gap between saying and showing, representing in words but not narrating, introducing the image without providing its immediate gloss, so to speak. By not providing a gloss to the picture it imagines, hypotyposis resembles an emblem without a gloss: it allows the pictura to take on several meanings.

- So, too, does drama. That the gloss is not provided

to the audience of a dramatic production does not signal that the mythological

figure to which it alludes is not used in an emblematic manner—that it is not

figured as a dramatic analogy to the image in an emblem book or illustrated

edition. Rather, the absence of a gloss frees the audience from a

pre-established interpretive frame and prompts him/her to configure that frame

by him/herself. For a sixteenth-century audience conversant with the

hermeneutics of emblem books, a single image is printed in a number of

different contexts, and thus articulates a number of readings either in bono

(in good part) or in malo. Thus, the copia pertaining to a

sixteenth-century audience member’s world of potential emblematic references,

as evoked by events and images on (or off) stage, does not just create a new

characterisation, a sewing together of an accumulation of several

representations and readings, but also initiates a simultaneous process of

elucidation of the classical allusion.

- In

the case of Titus Andronicus, what is off-stage, Tereus/

Chiron-Demetrius cutting Philomela/ Lavinia’s tongue, and merely alluded to in

the decorative arts, as the early seventeenth-century New York Metropolitan

Museum of Arts bed valance tapestry testifies, is illustrated in emblem books

and Illustrated Metamorphoses.[4]

Mythological books may supplement what is not actually seen on the stage,

providing the audience with images, and with a stock of possible

interpretations and representations, acquired by its potential knowledge of mythology

through illustrated volumes of the Metamorphoses or other works of art.

- To refer to a mythological event in a play that

has been inscribed into an emblem tradition is certainly not sufficient to turn

it into an emblem in the performance text. On the contrary, the mythological

story foreshadows the events to come in the play and helps the audience to

superimpose their emblematic knowledge on the performance text in order to

decode it. What, then, of Lavinia recast as a classical Philomela and its modern

adaptations? Lavinia is silenced and submitted to Philomela’s plight, but she

eventually suffers from a punishment that exceeds Philomela’s, since her

rapists not only cut out her tongue, but also cut off her hands, and since she

does not gain freedom and speech through metamorphosis after her revenge, but

is killed instead. This has become a familiar locus of feminist readings and

has already been analysed by a number of enlightening studies.[5] I will focus on her

mutilated body on stage, which seems to function as the present/absent

mythological emblem of Philomela in the play.

- To Elizabethans, Philomela’s story is well-known

(Ovid, Metamorphoses VI: 426sq.). She is raped

by her brother in law, Tereus, who cuts her tongue out to prevent her from telling

her misfortune to her sister, Progne. A skilled weaver, she succeeds however in

creating a tapestry unfolding her plight. After seeing her tapestry, her

sister, the wife of Tereus, kills her son Itys (in a maternal infanticide that

caused her to be compared to Medea in some emblem books) and serves him in a

pie to her husband. Notably, several segments of this story are found in emblem

books, but, at least in the companion text, the focus is often put on Progne’s

revenge rather than on Philomela herself, even if she can be seen in the pictura.[6]

- A survey of a number of mythological emblems about

Philomela’s story reveals varied thematic foci. Some emblems deal with this

Ovidian episode and link it to the theme of revenge. Nicolas Reusner’s Emblemata

(1581) in Book III, emblem 14, “In Prognen,” dwells on Tereus’ betrayal and on

Progne’s revenge on Itys. Other emblems also stress Progne’s anger and

subsequent revenge on her own son. Some others associate Progne with Medea. For

example, in Emblemata (1531), Andrea Alciati initiates this association

in his illustration of emblem 8b, which is then taken up by Held in emblem 112,

by Covarrubias in Book III emblem 80, and by Aneau in emblem 67. Barthélemy

Aneau, in Picta Poesis. Ut picture poesis erit also illustrates emblem

73, entitled “Impotentis vindicate foemina” with a pictura

showing Itys’ death and dismemberment. Similarly, Nicolas Reusner, in Emblemata

again, shows scattered human limbs on a dish, in emblem I.12, entitled

“Thyestaea Coena.” Another batch of emblems deals with the myth after the

transformation of Philomela into a bird.[7]

- So Shakespeare’s play also puts on emblematic

display what remained hidden in editions and emblem books. The emblem books I

have consulted never supply an emblematic representation of a raped and

mutilated Philomela; instead the stress is laid on the act of cutting out the

tongue as in the Bernard Salomon engraving.[8]

Shakespeare however twice creates this visual emblem, by combining

verbal/written and visual modes, by bringing Lavinia onstage and having Marcus

(2.4.11-57), and then Titus (3.1.66-86), comment on her body. A third

emblematic moment may also be identified when the body of Lavinia acts as pictura,

her words, “Chiron Demetrius stuprum” as scriptura, and the revengeful

words of her father as the gloss.[9]

This emblematic representation of Lavinia does not correspond to any “standard”

emblem iconography or interpretation that I could trace. Indeed, it is

well-known to Shakespeareans that Lavinia’s mutilation outdoes Philomela’s.

Because they know their Ovid, the rapists are keen to prevent Lavinia from

weaving a cloth that would reveal their identity, so they not only cut out her

tongue but further mutilate her by cutting off her hands. This theatrical and

unbearable mutilation heightens the violence of the play and contributes to

what Albert Tricomi has called the play’s “aesthetics of mutilation.”[10]

- It is precisely Lavinia’s violated

and mutilated body that Shakespeare stages in Titus, in order to present

the suffering female body as the trigger for revenge: “For worse than Philomel

you used my daughter / And worse than Progne I will be revenged” (5.2.194-5). Not

only Lavinia’s rapists, but also her father, know and set out to exceed the

myth. Filling a gap in emblematic literature, it is as if Shakespeare’s

performance text wanted to supply Lavinia’s body as Philomela’s, outdoing in

violence, spectacle, and horror the very emblematic literature to which it

alludes. Moreover, the appearance of Lavinia’s body onstage invites the

audience to stop and consider the point of view of the victim as much as that

of the avenger, and in stark contrast to the point of view of the rapists.

- The bitter dramatic irony of Lavinia’s appearance

onstage is that the audience knows what happened offstage, but her uncle and

her father do not. Yet Marcus intuitively associates his niece with the

classical Philomela:

Alas a crimson river of warm blood,

The move from the vision of Lavinia’s body to its aestheticised description is suggestive of the complex way in which “stories [taken from Ovid] about bodily violation [...] dramatize language’s vicissitudes” (Enterline 3). Analysing Ovid’s intertext Enterline shows that “[in Philomela’s story] poetic language and the ruined body insist on being read together” (Enterline 10). This may be what makes the disjunction between rhetoric and performance so blatant and affecting in Titus (all the more so in 3.1. when Marcus leads Lavinia to her father). As Enterline notes, “[…] Marcus speaks about [Lavinia] as if she were an aesthetic object, a marred beauty, best understood in terms of the dismembering rhetoric of the blazon. […] Lavinia endures yet one more male reading” (8).

Like to a bubbling fountain stirred with wind,

Doth rise and fall between thy rosed lips,

Coming and going with thy honey breath (2.4.22-5)

But sure some Tereus hath deflowered thee

And lest thou shouldst detect him, cut thy tongue (2.4.51-52)

- How does one stage this new paradoxical emblem? To

stage suffering is a most challenging issue: either it is overstated and the

audience remains impervious to its expression, or it is stylised, thus allowing

the audience to empathise from a distance. Two 2006 theatre productions will

help to comment on two different choices. First, a production given at the

London Globe, directed by Lucy Bailey, with a Lavinia drenched in blood; then a

production directed by Yukio Ninagawa in Stratford-upon-Avon the same year.

- Eleanor

Collins, reviewing Lucy Bailey’s production in Cahiers Élisabéthains,

notes that to present a cut-up Lavinia is such a shock that it breaks the flow

of the performance: “Audience members turn their heads away in real distress as

she shakes in shock-induced seizure [...]” (Collins 50). Her comments on the

“harrowing” (50) and “gory realism” (51) felt by the audience are echoed by Sam

Marlowe’s account: as Lavinia, Laura Rees begins the play as an ice-maiden and

object of lust for the jeering Roman mob, jostling among the groundlings.

Later, violated, her hands and her tongue cruelly cut away, she stumbles into view drenched in blood, flesh dangling from her hacked wrists, moaning and keening, almost animalistic. It’s the production’s most powerful symbolic image, redolent of the dehumanising effects of war.

[…] During the stomach-turning banquet that follows, he [Titus] bounces on his knee his raped and mutilated daughter, Lavinia, who, shrouded in white, resembles a grotesque, jiggling doll. It all accentuates the hideous stupidity of the play’s ghastly game of tit-for-tat, in which sex and power politics collide lethally.[11]

Illustration 1:Titus Andronicus, dir. Lucy Bailey, Shakespeare’s Globe (London, 2006), Davis Sturzaker (Lucius), Douglas Hodge (Titus Andronicus), Laura Rees (Lavinia), Richard O’Callaghan (Marcus Andronicus). Photograph by John Tramper, courtesy of Shakespeare’s Globe.

- According

to the reviewers of Bailey’s production, the suffering body of Lavinia was

“[A]lmost too ghastly to behold.”[12]

This is reminiscent of what happened also in other productions; for instance,

actresses playing Lavinia in the 1990s wanted to convey “the physicality of her

suffering” and prepared themselves accordingly (Aebischer,

“Silencing the Female Voice” 34).

- Yukio Ninagawa’s production harks back to Peter

Brook’s 1955 Titus, with Vivian Leigh as Lavinia and Sir Laurence

Olivier as Titus (Stratford’s Shakespeare’s Memorial Theatre, 1955).[13] It was produced and

presented during the Complete Works Festival (April 2006-April 2007), at

the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, in Japanese and “yraditional Japanese

stylisation, red ribbons streaming from maimed bodies or a cannibalistic dinner

party of impeccable decorum help[ed] ritualise the action” (De Jongh 630). Emotional verisimilitude does not possess the

degree of primacy in Japanese aesthetics that it does in the context of

Anglophone theatre. Ritualised drama is a more vivid and conspicuous presence,

and this source can be juxtaposed with the more recent emergence of a stylish

violent cinema. This was borne out as Ninagawa’s staging, and his physically

and vocally impressive ensemble, gave birth to a terrible beauty (Allan and

Revers 40). A

terrible beauty that some people obviously did not get.[14] Neil Allan and Scott

Revers thought otherwise:

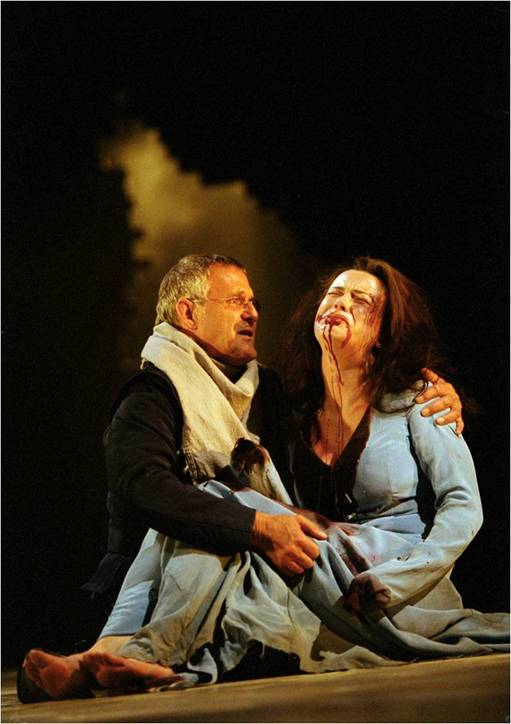

The psychopathic homosociality inherent in the conspiracy of Chiron and Demetrius was foregrounded, and was savagely consummated as, after desecrating Lavinia, they emerged embracing, ecstatic, naked, bloody torrents cascading from their genitals. The aftermath featured a carefully composed, almost still tableau, again indebted with Kabuki theatre with its aesthetics of stasis. Titus cradled Lavinia centre stage, rendering concrete the image of her as his own flesh, enveloping her in his robe.

Bloodshed and beauty created a stark dissonance, which was quite powerful. Distancing itself from the violence it stages thanks to “dissonance,” the production presents Lavinia onstage as if she were a painting.

Their position on the steps leading down from the stage recalled Michelangelo’s Pietà, while Marcus and Lucius flanked the scene like the wings of a triptych, the towering wolf standing in for a metaphysical point of reference (Allan and Revers 41).

Illustration 2: Titus Andronicus, dir. Yukio Ninagawa, The Ninagawa Company (Stratford-upon-Avon, 2006), Hitomi Manaka (Lavinia). Photograph by Ellie Kurttz, by courtesy of The Royal Shakespeare Company.

- As

in rhetorical treatises and emblem books, the eloquence of painting is

constantly referred to: ut pictura poesis, as painting, so poetry. To me

the dumb poetry of such a “speaking picture” does not alleviate the sufferings

described but it recaptures “the disquieting conjunction between poetic form and

sexual violence” (Enterline 9).

- The scenic picture displayed onstage demands

to be interpreted: what Enterline calls “the art of female complaint”

(11)[15]

is criticized by some feminist readings which stress the

portraying of the defilement of the female body through this disturbingly

beautiful figure of Lavinia.[16]

The pause induced by the forty-seven lines during which the body of Lavinia is

shown captures the audience’s attention: one of the effects of such a long and

static tableau, as noted by Pascale Aebischer, is to parody the fetishising

representations of femininity in which the woman’s “visual presence tends to

work against the development of a story-line, to freeze the flow of action” (Aebischer,

“Women Filming Rape” 140). Aebischer comments on the Petrarchan quality of this

stasis (140); the genre of the poetic blazon is here parodied and the fabula

of Philomela ironically superimposes actual violence onto the female body and

poetic love discourse. And indeed this shows that contemplating an emblematic

tableau is not synonymous with univocity of meaning; on the contrary, the

mythological figure that superimposes itself on the body of the actor/actress

opens up new possibilities of interpretation, based on multiple and different

encounters with and understandings of the mythological text.

- When Shakespeare creates a dramatic emblem he does

not dramatize the paragon but rather places Philomela at the centre of a

visual and verbal representation, thus visually embedding mythology as a

heuristic tool for the audience. Contemporary representations of Lavinia, using

an emblematic grammar and an aesthetised fixed tableau, vividly reconfigure the

Ovidian concern to make sexual violence and beauty clash. Shakespeare’s

invention, as demonstrated by contemporary performances, is to turn Lavinia

into a mute “speaking picture” (as emblems were often called).

- Modern productions like Ninagawa’s recapture the

sense that “Ovid highlights the cruelty of sexual violation, showing the part

of violence and degradation as clearly as the erotic element. Rape is not

mystified or romanticized but presented as a malevolent and criminal action”

(Ravdal, Ravishing Maidens qtd. in Enterline 20). By creating a visual

emblem, so forcibly staged by Ninagawa, Shakespeare figures Lavinia as the

silent and mutilated Philomela whose mutilated body does not appear in the

corpus of emblem books. He thus gives a visual embodiment of female suffering

when faced to the “unspeakable,” endowing a woman raped offstage with

corporality. Contrary to the standard reception of this myth in the early

modern emblematic context, Shakespeare creates a fixed image, an emblem of a

suffering body. Ninagawa’s stylized staging of the play seems to capture

Lavinia’s emblematic figuration.

- The distancing caused by what is read by some

critics as the so-called flaw of this long Ovidian monologue is due to the

extreme tension between a verbal description of what happened and what the

spectator can actually see by him/herself. This aims at stylising and mediating

violence, through empathy with the gens Andronicis’ sufferings, whereas

a staging that would significantly reduce this long monologue would rather

centre personal reaction on the violence of the emotion felt. Gregory Walker in

his review of a 2003 production of Titus Andronicus by Bill Alexander

for the RSC in Stratford explains:

[...] Shakespeare has his character react to events with a prolixity that suggests insincerity to the modern ear. To his great credit, Bill Alexander did not shy away from the problem, rather he made the disjunction between rhetoric and performance one of the issues to be explored (59).

In Alexander’s production, Lavinia is represented in a realistic style.

Illustration 3: Titus Andronicus, dir. Bill Alexander, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Royal Shakespeare Theatre (Stratford-upon-Avon, 2003), Ian Gelder (Marcus), Eve Myles (Lavinia). Photograph by John Haynes, by courtesy of The Royal Shakespeare Company.

- Again,

as Walker explains: “[She] stood twitching and whimpering downstage left, her

powder-blue gown ripped and stained with gouts of dark, red gore, her face

disfigured by bruises and her mouth cruelly slit deep into her cheek” (58). Her

father stood opposite on the stage, spatially and morally distant from her: “he

remained distant to deliver the three long speeches that describe his emotions

in set terms” (59). Far from being emblematic as in a morality play, the body

of the actress becomes the bearer of a meaning to be deciphered: like the

picture in an emblem book – yet, with a difference.

- Mimetic representation is not at stake; what

matters here is to draw the spectator’s attention to the process of reading a

body that can be so horrible that it may paradoxically cause him/her to smile.

The body becomes an icon of suffering. Titus says that he will learn to

interpret the dumb, and static, Lavinia:

This breviary of interpretation, mirroring the audience’s heuristic activity, in which Lavinia’s body forms then a first emblem of suffering (in 3.1 and 3.2), raises once again the issue of interpreting the classical fabula. This is what a staging of Lavinia’s body as a tableau underlines and draws the modern audience’s attention to.Speechless complainer, I will learn thy thought;

In thy dumb action will I be perfect

As begging hermits in their holy prayers.

Thou shalt not sigh, nor hold thy stump to heaven,

Nor wink, nor nod, nor kneel, nor make a sign,

But I of these will wrest an alphabet,

And by still practice learn to know thy meaning (3.2.39-45)

- 4.1 offers the second emblem, even more explicit.

What matters here is the functioning of a heuristic code signalled by the use

of The Metamorphoses as a prop:

Soft, so busily she turns the leaves.

From an Illustrated Ovid to a true-to-life embodiment, Lavinia’s plight oscillates between illustration and emblematic synthesis: the moment when the image is brought to a standstill, interconnecting several layers of interpretation.[17] Books are substitutes for speech, showing Lavinia’s plight. A media of communication in Shakespeare’s drama, the mythological story on the written page is substituted for Philomela’s woven tapestry in the Ovidian version. The use of Ovid’s text, and its presence onstage, realize Enterline’s stress on the fundamental fusion between the realm of the symbolical and the physicality of the classical story:

Help her. What would she find? Lavinia, shall I read?

This is the tragic tale of Philomel,

And treats of Tereus treason and his rape,

And rape, I fear, was root of thy annoy (4.1.45-49)Capturing in one figure a Roman commonplace for the aims of rhetorical speech (“movere,” to “move” one’s audience), Ovid tells us that [Philomela’s] tongue has motion and that it moves those who listen. Rhetoric, in the story of Philomela’s tongue and tapestry, means taking the idea of symbolic action very seriously. It means acknowledging that the body is a bearer of meaning as well as a linguistic agent, a place where representation, materiality, and action collide (6).

This duality already present in the Ovidian tale underlines once more the paramount role of Philomela in connexion to Lavinia.

- Female suffering is presented as it is

re-presented in this play: words imposed upon the suffering Lavinia distance

the audience from the sheer violence they see. Ninagawa’s choice to represent

Lavinia in accordance with a contemporary adaptation of Kabuki codes,

demonstrates on stage the transposition Shakespeare achieved when he moved the

Ovidian story to the stage while retaining an

emblematic style.

- Emblematic and iconographic

commentaries tend to over-inform theatrical imagery and our understandings of

them. We could wonder if in the end, the emblematic frames we see onstage,

along with the distancing they seem to effect, are only mental images that we

bring to a play or effects that we somehow project onto the stage. To me,

however, Ninagawa’s production overly stages the allusions that might frame our

understanding of the play, including the play’s allusions to the emblematic

tradition.[18]

- Are modern productions dramatizing the paragon of Philomela in a new way? Directors might not be concerned with questioning the reliability of the emblematic code, since interpretive codes have changed and the horizons of expectations of a modern audience cannot be compared to those of the sixteenth-century public. Yet, and arrestingly to me, even if the genre of the emblem is no longer familiar to audiences, the two types of productions that I have examined suggest that staging techniques may be closer than we think to what could be a Renaissance understanding of the play. Ninagawa’s work distances itself from cruelty, as the spectacle of suffering is stylized. Ribbons that represent blood, the symbolical code of the mater dolorosa (or pietà) transposed on the father’s attitude, are symbolic means of filtering the aching spectacle of an abused daughter, and yet the spectacle retains its shocking potential and its power of empathy all the while intellectualising it. Code for code, the functioning is thus reconfigured to suit a twenty-first century audience. From the biblical to the mythological realms, it seems that emblematic art and living contemporary theatre share this need to build on stock images while transforming and adapting them.

Notes